56°01′20″N 12°44′57″E / 56.02222°N 12.74917°E

Ramlösa hälsobrunn ('Ramlösa health well') (Swedish pronunciation: [ˈrâmːˌløːsa])[1] is a mineral spa located in Ramlösa in southeastern Helsingborg, Sweden, founded on 17 June 1707 by Johan Jacob Döbelius.[2] The well was built around a chalybeate (iron-containing) spring, which Döbelius investigated in 1701, 1705 and 1706. During the 18th century, the reputation of the well increased and it was visited by guests from both Sweden and Denmark.

Ramlösa well had its heyday in the early 19th century, when several members of the royal family and members of the nobility visited the facility regularly. In the late 1890s, a new and more mineral-rich alkaline spring was found, which was the start of bottled water in the country and the modern Ramlösa company. At the same time, the original activity of the mineral spa declined, and it was finally closed in 1973. Following threats of development in the 1970s, several of the buildings were protected as listed buildings and almost the entire park was classified as a protected area within the listed buildings designation.[3]

History

Discovery and establishment

Rumors about the chalybeate springs in Ramlösa and their curative effect had existed for a long time. During the Scanian War of 1675–1679, Charles XI's soldiers were said to have come there to recuperate. In Sven Lagerbring's description of the life of the field marshal Count Ascheberg, Kansliråd, it is stated that in 1677, soldiers who were plagued by field sickness (fältsjuka, outdated term for infectious gastrointestinal ailments among troops) recovered after quenching their thirst at the spring at Ramlösa.[4] At the end of the war, in 1679, the Swedish headquarters were located in Western Ramlösa.[5] The governorate physician and professor of medicine at Lund University, Johan Jacob Döbelius, drew attention to the well water in Ramlösa at the beginning of the 18th century. Although he had been warned by the inhabitants of the village about robbers in the forest where the spring was located, he examined the water several times: in 1701, 1705 and 1706. The water had the same composition as the water in several of Sweden's surbrunnar (lit. 'acid wells') [well containing naturally carbonated water with high iron content]: iron in the form of carbonated iron oxide. After this, Döbelius wrote about how the water's curative effect counteracted several ailments:

Scurvy, trembling of the joints, gout and arthritis, vertigo, headache, respiratory conditions, watery and red eyes and red face, heart palpitations, short temper and mean spirit, constipation, spoiled and hard stomach, constipated liver, jaundice and melancholy, kidney and bladder stones, hysteria, strangury, vaginal catarrh, and this water is also used for all kinds of menstrual disorders. [6]

Young people, not yet educated, who have falling sickness, which is usually caused by an engorged stomach or worms, can also seek health at Ramlösa well. But those who have been deaf from their youth, have had cataracts, or those who have tuberculosis, as well as elderly people with falling sickness, have no restitution to expect at this health well.[6]

Döbelius turned to the then-governor of Scania, Magnus Stenbock, who gave permission, and help, to clear around the well. On 17 June 1707, on the 25th birthday of Charles XII, the well was inaugurated.[7] A thousand people had gathered at the well to drink its water, but when Döbelius pointed out that they had to stay at the well for a longer period of time, the number of patients was reduced to about 40.[7] In 1708, Döbelius published a book entitled Beskrivning om Ramlösa hälso- och surbrunnens uppfinnande, dess belägenhet, natur, verkan och rätta bruk ('Description of the invention of the Ramlösa health and surbrunn, its location, nature, effect and proper use'), in which he tells of patients for whom the mineral water had an effect. The year after the opening, several patients returned and word of the well spread, especially among the gentry, thanks to Döbelius' dual role as a prominent physician and businessman. The well developed into a clinic and hospital where many sick people went to drink the water. The treatment likely consisted of drinking 15 to 17 glasses of the Ramlösa water every morning to cleanse the body. In addition, a lively entertainment life developed, with people from various social classes gathering to socialize in the spring's surroundings.

After Döbelius, medical doctor Hans Roslin took over the well in 1713, but when he was appointed provincial physician in Kristianstad, he lost contact with the facility and in 1727 the city physician in Malmö, Kilian Stobæus, was instead appointed as well doctor.[8] It was largely thanks to Stobæus that Ramlösa's reputation as a health resort grew, largely because of his good contacts, including in Denmark, but also because of his popularity as a doctor; although Stobæus was sickly and had a limp, he always cared for his patients.[9] Stobæus had several disciples, among them Carl Linnaeus, and he remained as a well doctor until his death in 1742, although his followers took care of the patients in the later years.[9]

Linnaeus was to return to Ramlösa, together with his student Olof Söderberg, during his trip to Scania in 1749. During his visit to Helsingborg, he stayed with the mayor, Petter Pihl the Younger, at his residence Gamlegård, and then travelled from there to Ramlösa mineral spa. About the well Linnaeus noted:

The Ramlösa surbrunn was located a quarter of an hour from Hälsingborg to the south, in as pleasant a place as nature could provide. The land to the north, which was covered with the most beautiful deciduous forest, was interrupted perpendicularly to the south by a high sandstone wall, which was so soft that it could be cut and carved, which through a hole on the wall itself released with a leap this good-tasting and easily drinkable health water.

...The well was now visited and drunk by many guests, who came here from distant places, and many found here their health from a water, which is one of the most distinguished surbrunn waters in the kingdom though not the strongest in iron content.

...Flowers were selected, to see on them what hour they opened or closed, and thus to bring into existence the Horologium Floræ, flower clock, on which I have been working for several years, and by which one may be able on the wild earth, though under a cloudy sky, to tell the time as accurately as by any clock.[10]

.jpg.webp)

Around the middle of the 18th century, a long timber-framed well house was built with only five guest rooms. Most of the guests at Ramlösa well instead rented accommodation from locals. The same year Carl Linnaeus visited Ramlösa, 1749, architect and court superintendent Carl Hårleman also visited the well. Hårleman described the well's guests, who during his stay consisted of retired soldiers and ordinary peasants as well as diplomats and civil servants.[11] Hårleman had a runestone erected to commemorate his stay at the well. The stone was placed on the hill opposite the well house and the runic inscription reads:

Karl. Hårleman. med. sin. hustru. H. I. Liewen. reste. denna. sten. til. taksamt. minne. af. Ramlösa. vatns. dygd. ok. grevinnan. Ramels. omvårdnad. År. M.D.L.L.L.L.L.[12] |

Karl. Hårleman. with. his. wife. H. I. Liewen. erected. this. stone. in. grateful. memory. of. Ramlösa. water's. virtue. and. countess. Ramel's. care. Year. M.D.L.L.L.L. |

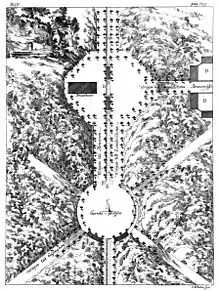

Before Hårleman's visit, the area around the spring had not been maintained in any particular way, but had retained its natural form. In his memoirs, Gustaf Adolf Reuterholm describes how his mother, on a visit in the 1730s, had found the mineral spa divine in its primitive appearance, describing it as "made only by nature, but so marvelous that art could not have better established it".[13][14] Hårleman became one of the initiators of the rehabilitation of the spring. The area was enclosed, new trees were planted and new roads and paths were laid out.[15]

Company establishment

Ramlösa well flourished under the stewardship of Eberhard Rosenblad from 1760 until his death in 1796.[16] During this time, the number of visitors increased considerably and attempts were made to purchase land adjacent to the well so that a new hotel could be built there with room for 200 guests. However, none of the neighboring farms were willing to sell, as they would then lose income from the well's guests who rented accommodation for the summer.[17] To capitalize on the well's popularity, a limited company was set up to raise capital for the maintenance of the facilities.[18] The first owners consisted mainly of Scanian landowners, but also of doctors and merchants. The first board of directors consisted of County Governor Gustaf Fredrik von Rosen, Major General Bror Cederström, Secretary of State Christoffer Bogislaus Zibet, merchants Carl Magnus Tönningh and Carl Magnus Nordlindh, then-well doctor Pehr Unge and Baron (friherre) Rutger Macklean.[19] In the same year, a request was sent to the king, Gustav IV Adolf, to acquire new land in this way. The king not only granted the purchase, but also had a plan drawn up for the well's expansion, and von Rosen thus succeeded, through the state, in buying half a manor (frälsehemman) in Köpinge for the well.[18] In 1801, the well received its first royal privileges, which stipulated that it was entitled to charge for the water from the well's guests.[20] The fee for the well house was one riksdaler. Wealthier people had to pay two riksdaler and the common people 24 shillings. The priest, bell-keeper and well-keeper were paid at discretion.[4] However, the poor could still drink from the water free of charge.[20] With the help of the new share capital of 16,000 riksdaler, it was possible to expand the facility; for example, the well house was rebuilt, a new guesthouse – now the doctor's villa – was added, new stables were built, and four new buildings for guest rooms were constructed.[21] A bathhouse was built on the beach between Helsingborg and Råå, where guests were taken by horse-drawn carriage, but it burned down in 1811.[21] The bathhouse was located on the town's land. It was 28 ells long and 15 ells wide and had been donated to the well by one of the members of the well board, Tönningh.[4] In addition, several landowning families built villas around the park, including the Trolle, Dücker, Hamilton and Wedderkopp families.[21]

The guests of the well stayed in Ramlösa or Köpinge and also in Helsingborg. Drinking from the well was accompanied by loud music. There was dancing every Sunday and Thursday between 4:00 and 7:00 p.m. There was also a visit to the Comedie House in Helsingborg. Twice a week collections were made for the poor and medicines were also given to them for free. There was no hospital, so the poor were accommodated in barns and lodges in Ramlösa and Köpinge. In 1802 a special dwelling house was built for the poor. The number of guests had increased over the years: in 1796: 74, in 1797: 55, in 1798: 81, in 1800: 106 and in 1801: 110. If the poor were also included, the number of guests at the well was almost 200.[22]

von Platen and von Dannfelt

Due to the many new buildings, the capital soon ran out, which meant that the court marshal Achates von Platen's proposal to lease Ramlösa Well for 50 years was gladly accepted.[23] Together with the well doctor Eberhard Zacharias Munck af Rosenschöld, von Platen was responsible for the well's new glory days, von Platen through his investments and expansions of the facility and Munck af Rosenschöld through his contacts who built up the reputation of the mineral spa as a social haven. In 1807, for example, von Platen had the first hotel built within the grounds of the well: the "Great Hotel" – a 40-meter (130 ft) long and 15-meter (49 ft) wide two-storey timber-frame building with a large salon, two halls and four large guest rooms on the ground floor and 20 guest rooms in total. He also built new stables for a total of 44 horses and ten carriages and made improvements to the park. Five barrels of the 70 barrels of land to the west of the park owned by the well were set aside for gardens and the planting of 100 fruit trees. Despite doctor Munck af Rosenschöld's many disagreements with King Charles XIV John, as a liberal member of parliament,[24] many members of the royal family visited the park regularly. Crown Prince Oscar (later Oscar I) in particular was a frequent visitor.[25] The royal splendor attracted Scanian society, as well as much of the capital's upper class, to balls and other events. The period was depicted by the publicist Bernhard Cronholm as follows:

Through the frequent royal visits, Ramlösa had become a place where the fine world gathered from all over Scania every summer. During the four weeks of the actual season, life was bustling and splendid. The promenades were at certain times of the day filled with exquisite toilettes [elegant dress], while horsemen presented themselves on English thoroughbreds, and a collection of carriages with whirring harnesses and goldsmiths formed brilliant processions on the road between the fountain and the town.

Youth, beauty and talent celebrated their Olympic games here. Every young girl who was, as it is said, going out into the world, had here to undergo the ordeal before the critical areopagus [court], and the verdict passed here was regarded as the verdict of the highest authority in the world of gratias, chivalry and taste. An etiquette as strict as that of a Gustavian court prevailed, and this often resulted in a stiff tone and a way of life which otherwise bore little resemblance to the unpretentiousness required by one who travels to a well to nurse one's health.

The guests of the well were divided into different societies, and it was only those who were healthy and those who belonged to the higher social classes who took part in the costly and glorious life, while the others lived more leisurely and were spectators of the glorious state of affairs. At that time the fountain had certain habitués [regulars] who came every year. Several families had homes there and others came regularly every summer. Young people liked to come there, because they always had fun.[26]

In 1824, von Platen transferred the well to Colonel Carl von Dannfelt for 18,000 riksdaler and soon Dannfelt also owned the majority of the well's shares.[27] Dannfelt built on what von Platen had started; for example, he rebuilt the bathhouse at Öresund and a new hospital was built in the eastern side of the area with room for 80 patients. The park was further refurbished in the romantic English style, with walkways designed to attract visitors.[28] During this time, entertainment was lively and several balls and concerts were held at the well, guests could rent horses for excursions, and there were opportunities for card and billiard games. In 1824, Charles XIV John visited the park and the possibility of building a special residence for the royal family was discussed when they visited the well.[29] But when the plans were presented in Stockholm the following year, the king had changed his mind and instead chose to donate a sum of 8,000 riksdaler to the park, to be used to subsidize stays for those who could not afford to rent the well themselves.[29] This donation laid the foundations for what was to become the well hospital, which was completed in 1835. It became one of the most lavish buildings in the park and housed 46 hospital beds.[30] In 1828, Queen Désirée visited the well and in her honor Dannfelt had a "Queen's Garden" planted in front of the house she lived in, now known as Villa Desideria.[25]

Frequent changes of ownership and the new company

In 1840, the well suffered a major setback when both the popular Doctor af Rosenschöld and the owner Dannfelt died within a year.[31] There followed a period of many changes of ownership and great confusion. Dannfelt's relatives, who had inherited the majority of the shares, transferred the lease to Lieutenant Påhlman in 1842 and then sold it to the manager Olof Westergren.[32] Westergren died in 1849 and the unclear ownership of the well led to fears that the well would be split up, so twelve farmers got together and bought the well the same year.[32] However, ten of the farmers withdrew the following year, which meant that the well was then owned by the gardener Carl Hultberg and estate owner Jöns Pålsson. Pålsson's father bought the well in 1853, but died shortly afterwards. His heirs planned to divide up the surrounding land and sell it off, and at the same time the 50-year lease from 1805 was about to expire, so in 1855 a new company was formed by Scanian businessmen, headed by Ryttmästare (cavalry captain) Rudolf Tornérhjelm, who took over the well.[33]

The new company began an intensive period of refurbishment and new construction, with a new bathhouse built at the spring, the old well house demolished and a new hall completed in 1862, paths built and trees felled to open up the park.[34] In 1865 the park's communications were improved with the completion of the railway to Landskrona, along which Ramlösa had its own station, located where the present Ramlösa Station is. In addition, a few years later a number of horse-drawn buses began to run between Helsingborg and the well.[35] In 1875, train connections were further improved when the Helsingborg-Hässleholm railway was built and the track was laid just south of the well park. A second station was established for Ramlösa, Ramlösa Well station.

With the help of the financier Wilhelm Kempe, the doctor Curt Wallis took over the well in 1876, both as owner and manager.[36] Wallis refurbished the aging facilities, for example building a bathhouse by the sound, containing both a restaurant and a music pavilion, which he connected to the park with a horse-drawn railway – Sweden's first when it opened in 1877.[37] New villas were built, increasing the number of rooms from 100 to 170. In 1879, the old hotel burned down and was replaced a few years later by a new and larger one, which is largely the hotel that remains today.[38] Wallis did much to restore the reputation of the well after the somewhat chaotic period, and it was to his credit that the Ramlösa mineral spa survived the end of the 19th century.[39]

In 1882, the well's owner changed again. This time it was a consortium of Swedish and Danish investors. They transformed the well park into a more leisure-oriented park, Fjället ('the Mountain'), containing a miniature amusement park, a dance floor, shooting range, saloon and more.[40] The amusement area was set up on the hill north of the spring where flowers and trees were planted. All these investments attracted large numbers of visitors, who from 1891 could reach the well by means of a new narrow-gauge railway: the Decauville, or "Little Ghost", as it was also called.[41] On the other hand, faithful well visitors found it difficult to recognize the new surroundings and the well doctors did not stay particularly long each season because of the disorder.[42] In 1896 Folkets Park in Helsingborg opened, taking a large proportion of the amusement park visitors, and by the end of the 19th century the traditional well business had returned to normal.[43]

New well and decline of the spa

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

At the end of the 19th century, drilling for coal and clay was carried out in the area around the park, but instead large amounts of water were encountered, which caused drilling to be stopped.[44] At the same time, Doctor Claus, the manager of the well at the time, had problems with limescale in his steam boilers. At the suggestion of the managing director, Baron Uggla, they tried to replace the stream water with water from the borehole, and to their great delight the limestone disappeared.[45] This led to the water being analyzed; results showed that it was very pure and rich in minerals, on par with the best German health water, Apollinaris, from Bad Neuenahr.[45] However, it was not until the beginning of the 20th century that a bottling plant was set up. The first factory was built in 1912 and was located next to the bathhouse in the park.[46] Sales were slow at first, but in 1914 they picked up and sales increased by 50 percent.[47] At the same time, rumors began to circulate that the original well was dying, as it appeared to be, and the management tried to cover it up.[48] However, on closer inspection it was found that the pipes had burst again and the problem was solved by installing new pipes. At the same time, further drilling was carried out and another spring was found with better water quality than the old one.[49]

In the 1920s, the income from the water-bottling plant was greater than that from the traditional well operation.[50] The reason for this was that society now had better health care facilities, which eventually competed with the mineral spas.[51] In the 1930s, sales of bottled water continued to increase. The market had now expanded abroad and, in addition to Denmark, where Ramlösa had long been known, the water was exported to Finland, Great Britain, the Netherlands, France, Turkey, Syria, Mandatory Palestine, and Egypt.[52] The old well had finally become a financial burden for the company and was kept mostly for tradition's sake. Sales declined during World War II, and instead several of the park buildings were used as refugee facilities for Jews fleeing Denmark during the expanded persecutions that began in 1943.[53] Then, on 9 April 1945, released prisoners from the German concentration camps arrived in Folke Bernadotte's white buses in Helsingborg and many of them were received at Ramlösa well.[54] From 1943 to 1945, over 13,000 refugees were received, 200 to 700 per day.[55] When peace returned, the turnover of the water-bottling plant rose sharply, which meant that the plant had to be expanded on two occasions, and finally moved to a completely new plant in the Ättekulla Industrial Area in 1973. The same year, the spa operations were finally closed down at the mineral spa. That year the well hospital had 66 patients.[55]

Even before the closure of the well, plans had been made for the use of the park area and buildings. In 1967, AB Ramlösa Brunnsanläggning was established with the aim of creating a year-round well, where the old environment was to be preserved without any radical changes.[55] However, two of the main owners, the construction companies Hermanssons Byggnads AB and JM Byggnads AB, were opposed and felt that the operation could not be maintained without extensive building projects to finance it. One of the plans was to demolish the old Great Hotel and replace it with a service building containing a gallery, library and conference facilities.[55] They also wanted to demolish the bathhouse and build tennis courts. In addition, a major hospital pavilion, townhouses and a 13-storey hotel building were to be built. These plans met with strong protests, led by Hans Alfredson among others, and in 1973 the company instead donated the park to the city and was content to build a townhouse area outside the park.[55]

Well managers 1707–1973

|

|

Medicinal properties

According to the well manager Pehr Unge, the water had proved effective against the following diseases: nausea and vomiting in the mornings, constipation, colic, phlegm and insomnia, chest pain and heartburn, flatulence, worms, melancholy, hysteria and convulsions as well as menstrual disorders, gout, rheumatism, contractures, urinary tract disorders, paralysis and even skin conditions. He also cites a couple of diseases in the chest that have been healed by the water.[56]

Ramlösa Hälsobrunn

Today's Ramlösa Hälsobrunn (business) has its roots in the old limited company founded in 1798, although today's operations are entirely different. Today the business consists only of bottling the water from the various wells of the old business. The company was bought by Norwegian conglomerate Orkla in 1995.[57] AB Ramlösa Hälsobrunn ceased to exist as a separate company in 1999 and since 2001 the business has been part of Carlsberg Sverige AB,[57] which is owned by the Danish brewery group Carlsberg Breweries. The plant bottles over 80 million liters of water annually,[58] of which about 10% is exported to various countries.

Well park

Park design

The park is situated around a natural valley in the landscape, which can be said to divide the park into three different parts, a southern part consisting of the mineral spa buildings and a number of villas, the part down in the valley containing the springs and the well pavilion, and a northern part consisting of deciduous forest. The park has elements of both a French park with long shoulders and sight lines and an English park with undulating lawns.

At the southern end there are two older official entrances, one to the west and one to the east. From the western entrance, where one can see a preserved wooden entrance corridor of unknown date, one is led through a long avenue, now known as Von Platen's allé. The trees in the avenue were formerly linden trees , but are now mostly horse chestnut, which create a dense canopy over the road, but also elm, linden and maple. The avenue is bordered on both sides by an English park with elements of a number of residential buildings, up to the Great Hotel, where the park finally opens up. In front of the main entrance to the hotel, on its northern side, there is an open space paved with gravel and to the north a shrub-fenced garden with fountains and flowers, laid out in the 1930s. To the north of the garden are the timber-frame houses Villa Linnea and Villa Viola and beyond this the old bath house. Further east from the hotel is a row of villas on the north side of the walkway, Villa Bellis, Villa Salvia and the Doctors' Villa, and to the south is the Accountant's Villa. At the back of the corridor is the well hospital and just before it the corridor branches off to the south to lead to the second entrance gate. Previously, a poplar avenue led from here down to the spring in the valley. However, the alley no longer exists.

The part of the park located in the valley, usually referred to as the Ramlösa Valley, has an open character with large grassy areas interspersed with a number of smaller trees and shrubs, where rhododendrons are abundant. This part has an intimate feel as it is bordered on both sides by steep slopes with compact greenery, giving the impression of being enclosed. In the eastern part is the Water Pavilion, built in 1919–1921, just south of the original iron spring, marked by the exposed rock wall, stained red by the ferruginous water. Various concerts and events are held here from time to time, especially on Well Day. At the centre of the open grassy area, towards the valley slope, is another spring, the old alkaline spring. This is enclosed by an artificial cave, now enclosed by a fence. The valley is home to a number of unique biotopes for lichens, fungi, insects, birds and plants.

From the Ramlosa Valley, the so-called Philosophical Path leads up to the second hill, which consists of a mixed deciduous forest that used to be dominated by oaks and was therefore called Ekebacken ('the Oak Hill'), but nowadays the proportion of beech has increased. Along the path are several initials carved into the trees, as this was a popular romantic walking route in the days of the mineral spa. At the beginning of the Philosophical Path stands Hårleman's runestone (1750), donated and designed by the 18th-century architect Carl Hårleman, where he gives thanks for a refreshing stay.

The park is home to a number of unusual trees, including Caucasian wingnut (Pterocarya fraxinifolia), Turkish hazel (Corylus colurna) and dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) around Villa Primula. There is also a large tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera) between the villas Bellis and Salvia, which offers a heavy flowering display in early summer, as well as plane tree (Platanus acerfolia) and false acacia (Robinia pseudoacacia) at Villa Malvia. To the east of the Grand Hotel grows a chestnut tree (Castanea sativa).[59]

Park buildings

There are 22 individual buildings in the park. In order to protect the park's buildings from development threats such as those in the 1970s, 13 of the buildings in the park were protected by being listed between 1973 and 1974, but almost all of the buildings are protected as the park is part of a conservation area covered by the listed building designation.[60]

Historic buildings

- Doctor's villa

- Ramlösa Well Hotel

- Bath house

.jpg.webp)

- Water Pavilion

- Villa Bellis was built in 1807 and is a yellow-painted wooden building with lock panels on one floor with a mansard roof. The corners of the building, window linings, verandas and balconies are painted white. The building was constructed as a semi-detached house, i.e. with accommodation for two families, and therefore has two entrances, both of which are located on the south long side of the building. The entrances are set on the porches with glazed sides, on which balconies are placed and between which there are two more balconies. Apart from the two balconies on the porches, the building is identical to Villa Salvia. The architect is unknown. The house became a listed building in 1973.[61]

- Villa Iris is a one-and-a-half-storey white-plastered building, probably built in the early 19th century. The building has a gabled roof with red eternit fiber cement tiles, and metal-clad chimneys and dormers. The south façade of the building has a frontispiece with exposed timber framing and a veranda with a balcony above. The gables of the building also have exposed timber framing and the west gable also has a veranda. The villa was built as a private residence and therefore its construction is not recorded in the well's records until it passed into its ownership in 1878. It has seven rooms downstairs and eight rooms upstairs and is now a private residence. The villa became a listed building in 1973.[62]

.jpg.webp)

- Villa Linnéa was designed by architect Alfred Hellerström and built in 1896. The house is a one-and-a-half-storey angular building with a gabled roof and a façade of imitation timber framing with red patterned brickwork. The roof is covered with grey fiber cement tiles. Building details such as windows, balustrades and doors are painted in pastel yellow. The villa has balconies on both gables and a south-facing veranda has been added at the corner. The building became a listed building in 1973. The design and background are the same as the Pyrola, Veronika and Viola villas, although there are some individual differences.[62]

- Villa Malva was built around 1880 and is a wooden building clad in yellow painted horizontal panels. The house is on one and a half floors with a gable roof clad in red fiber cement tiles and the gable ends and the underside of the eaves clad in seam panelling with sawtooth frieze. The main entrance is located on the house's southern long side and is accentuated by a frontispiece, as well as a porch with a balcony above. Both gables have extended rooms with balconies on the roof. The building probably replaced a building on the same site that burned down in 1879 and consists of seven rooms on the ground floor and six rooms on the upper floor. The building became a listed building in 1973 and in 1977 the interior was converted to house three apartments.[63]

- Villa Pyrola was designed by architect Alfred Hellerström and built in 1896. It is identical to Villa Linnéa and was declared a listed building in 1973.[64]

- Villa Salvia was built in 1800 and is identical in design to Villa Bellis above, except that it has no balconies above the porches. The architect is also unknown and the villa became a listed building in 1973.[64]

- Villa Tora is the smallest villa in the park and was built sometime between 1878 and 1899. The building is single-storey with a strongly pitched gable roof clad in red fiber cement panels. The façades are divided into bays of white-painted timber profiles, with the spaces between them formed by yellow-painted standing chamfered panels at the level of the windows and varying horizontal and diagonal beadboard panels in the bays above and below the windows. The villa is adorned with rich joinery. The main entrance is located to the south under a raised dormer window. The building probably stood on another site in the past and may have served as a bathing pavilion or ticket office and waiting room for the horse-drawn railway.[65]

- Villa Veronika was designed by architect Alfred Hellerström and built in 1896. It is identical to Villa Linnéa, except that both gables have half-vaulted roofs, and like it became a listed building in 1973.[65]

.jpg.webp)

- Villa Viola was designed by architect Alfred Hellerström and built in 1896. It is identical to Villa Linnéa, except that it is mirrored and that both gables have half-vaulted roofs, and like Villa Linnéa it became a listed building in 1973.[66]

Other

- The well hospital (brunnslasarett) consists of two buildings, the oldest of which was built in 1835 and designed by architect Fredrik Blom. The building is a two-storey, yellow brick building with brickwork and a hipped gabled roof, with white profiled bands broken on the ground floor by the cornices of the windows, which are also white. The upper floor windows, however, have straight brick arches. The main entrance is located on the west façade of the building and is surrounded by white pilasters with black bases, which support a profiled cornice with the inscription LASARETT. The eastern long side has a two-storey extension which was added to the building in 1928. In 1982 there were plans to declare the building a listed building, but due to its poor condition, it never came to be. The second building is the hospital annex, which was built in 1885. It is a two-storey building whose façades are clad in yellow-painted recumbent beadboard with white knots and bands. Enclosures, balconies and other building details are also white. The house is covered by a hipped gable roof with red brick. The building was extended to the west in 1934.[67]

- The two-and-a-half-storey accountant's villa was built in 1829 in yellow plaster. The gable end is clad in chamfered paneling with sawtooth frieze, which, like the building's joinery, is painted brown. The windows, on the other hand, are painted white and are of the central mullion type with glazing bars, where those in the gable ends have white painted coverings. At the main entrance, on the north long side, the villa has an extended porch with an overhanging balcony with glazed sides, which in turn is covered by a small projected gabled roof. Above the balcony is a smaller paneled frontispiece, which has a similar counterpart on the opposite side of the house.[68]

- The office villa was built in 1932 and designed by architect Arnold Salomon-Sörensen. It is a single-storey building with a furnished attic and a half-vaulted roof covered with red tiles. The roof is interrupted on both long sides by frontispieces and on either side of these groups of three metal-clad dormers. In front of the southern frontispiece, a small extension protrudes on which a balcony is placed. The façades are covered in grey paneling, while building details such as windows, doors, and knots are painted white.[68]

.jpg.webp)

- Villa Begonia was designed by Ola Andersson and built in 1913. It is a two-storey building with a plastered façade, with corners articulated by white corner links and a tented roof of red tiles. On the east and west façades, the building has loggias at both corners, with separate openings with single staircases, leading out to the garden. The villa's four rooms could be rented by the well guests during the summer, but now the ground floor is used by a preschool.[61]

- Villa Desideria was built in 1801 for the Trolle family. It is a one-and-a-half-storey timber-frame house with brown painted oak and yellow brick in the bays. The building's long side façades have frontispieces to the north and south, while the gables have secondary porches to the east and west, added in 1899. The main entrance faces south and is located under a carved porch added between 1873 and 1879. The carpentry details are painted brown, except for the veranda balustrade and the windows and linings of the porch, which are painted white. The villa takes its name from Queen Desideria, the wife of Charles XIV John, who stayed in the villa during her stays at the spa. Previously, the house was called the Old Trolle House.[69]

- Villa Flora was built in 1920 and designed by architect Ola Andersson. It is a large, plastered two-and-a-half-storey building with a hipped gable roof and red tiles. Its southern façade has a projecting section with loggias on both floors. The site had previously been occupied by the New Trolle House from 1802, which was demolished in 1920. Villa Flora was built for renting out rooms during the summer well season and contained 20 rooms with 36 beds. In 1979, the building was renovated internally and converted into a multi-unit dwelling with eight apartments.[69]

- Villa Primula, also known as Villa Viktoria, was built in 1896 and is a one-and-a-half-storey angular building with yellow-painted sheet pile panels on the ground floor and pearl-painted ones on the upper floor. The roof is gabled with tiles and has two frontispieces to the south, one larger and centrally located and one slightly smaller on its eastern side. Below the central front porch is a smaller extension supporting an overhead balcony. The extension is flanked on the ground floor by verandas on either side. To the east is a pentagonal staircase tower, now converted into alcoves. Building details such as knots, skirting, linings and other joinery are painted white. The villa was refurbished in 1976 when the paneling, joinery and windows were replaced.[63]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Jöran Sahlgren; Gösta Bergman (1979). Svenska ortnamn med uttalsuppgifter (in Swedish). p. 20. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ↑ Nationalencyklopedin (1992). NE HF band 09 (in Swedish). NE Nationalencyklopedin. p. 257. ISBN 978-91-976240-8-4. OCLC 941582272.

- ↑ "Ramlösa brunn". www.lansstyrelsen.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- 1 2 3 Alfort 1842, p. 87.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 10.

- 1 2 Åberg, Alf: Facsimile of Beskrifning om Ramlösa Hälso- och Surbrunns Uppfinnande

- 1 2 Åberg 1957, p. 11.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 17.

- 1 2 Åberg 1957, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carl (1751). "Carl von Linnés resa till Skåne 1749: 11 juni". Carl von Linnés resa till Skåne 1749 (in Swedish). Stockholm. Archived from the original on 25 November 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ↑ Odd 1867, p. 37.

- ↑ Odd 1867, p. 38

- ↑ Odd 1867, p. 38.

- ↑ Sturzen-Becker, Oscar Patric (1862). Reuterholm efter hans egna memoirer: En fotografi (in Swedish). Stockholm-Copenhagen. p. 18. OCLC 487180835. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 29.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 38.

- ↑ Haas 2001, p. 12.

- 1 2 Åberg 1957, p. 40.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 41.

- 1 2 Åberg 1957, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 Åberg 1957, p. 44–45.

- ↑ Alfort 1842, p. 87–88.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 45.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 52.

- 1 2 Åberg 1957, p. 61.

- ↑ Johannesson 1987, p. 168–169

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 47.

- ↑ Haas 2001, p. 13–14.

- 1 2 Åberg 1957, p. 60.

- ↑ Haas 2001, p. 14.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 73.

- 1 2 Åberg 1957, p. 75.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 81–82.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 85.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 89.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 100.

- ↑ Ranby 2005, p. 68.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 106.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 108.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 109–110.

- ↑ Ranby 2005, p. 76.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 115.

- ↑ Haas 2001, p. 16.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 117.

- 1 2 Åberg 1957, p. 119.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 136.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 144.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 142.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 143.

- ↑ Haas 2001, p. 17.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 152.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 157–158.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 165–166.

- ↑ Åberg 1957, p. 172.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Haas 2001, p. 18.

- ↑ Alfort 1842, p. 89.

- 1 2 "Ramlösa hälsobrunn". Helsingborgs stadslexikon (in Swedish). 9 December 2016. Archived from the original on 30 January 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ↑ Ekström, Martin (2009). Mineralämnesförändringar i mineralvatten (in Swedish). Lund University/Livsmedelsteknik. OCLC 1017494301. Archived from the original on 2 February 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ↑ "Historien om Ramlösa brunnspark". Helsingborg stad (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 6 October 2011.

- ↑ Haas 2001, p. 38.

- 1 2 Haas 2001, p. 43.

- 1 2 Haas 2001, p. 45.

- 1 2 Haas 2001, p. 46.

- 1 2 Haas 2001, p. 47.

- 1 2 Haas 2001, p. 48.

- ↑ Haas 2001, p. 49.

- ↑ Haas 2001, p. 39.

- 1 2 Haas 2001, p. 40.

- 1 2 Haas 2001, p. 44.

Sources

- Alfort, Philip (1842), Handbok för brunnsgäster, Häfte 1: Beskrifning öfver Sveriges förnämsta helsobrunnar (in Swedish), Stockholm: L. J. Hjerta, OCLC 186054908

- Haas, Jonas (2001), Bevarandeprogram för Ramlösa (in Swedish), Helsingborg: Helsingborgs stad

- Johannesson, Gösta (1987), Sällsamheter i Helsingborg (in Swedish), Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren, ISBN 91-29-58267-9

- Nationalencyklopedin HF (in Swedish). Vol. 9. NE Nationalencyklopedin. 1992. p. 257. ISBN 978-91-976240-8-4.

- Odd, Orvar (1867), "Ramlösa Helsobrunn", Svea folkkalender för 1867 (in Swedish), Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag

- Ranby, Henrik (2005), Helsingborgs historia, del VII:3 : Stadsbild, stadsplanering och arkitektur. Helsingborgs bebyggelseutveckling 1863-1971 (in Swedish), Helsingborg: Helsingborgs stad, ISBN 91-631-6844-8

- Åberg, Alf (1957). Ramlösa: en hälsobrunns historia under 250 år (in Swedish). Hälsingborg: Killberghs bokh. (distr.). OCLC 472823598.

Further reading

- Rigstam, Ulf (2006), "Ramlösa hälsobrunn/Ramlösavattnet", Helsingborgs stadslexikon (in Swedish), Helsingborg: Helsingborgs lokalhistoriska förening, pp. 318–321, ISBN 91-631-8878-3

- Rigstam, Ulf, ed. (2005), Arkitekturguide för Helsingborg (in Swedish), Helsingborg: Helsingborgs stad, ISBN 91-975719-0-3

- Sjöbeck, Pontus (1918). En hittills okänd upplaga af Döbelius' beskrifning om Ramlösa (in Swedish). Vol. V. Lund: Nordisk tidskrift för bok- och biblioteksväsen. p. 239.

- Det alkaliska Ramlösavattnet (in Swedish). Vol. 32. Hälsovännen, Tidskrift för allmän och enskild hälsovård. 1917.

- Schimanski, Folke (2010). Tillbaka till livet. Ramlösa hälsobrunn som räddningsstation 1943, 1945 och 1956 (in Swedish). Region Skåne, Beredningen för integration och mångfald. ISBN 978-91-633-7137-0.

- von Döbeln, Johan Jacob. Beskrifning om Ramlösa hälso och surbruns upfinnande, dess belägenhet, natur, wärckan och rätta bruk (in Swedish). Gothenburg: Wezäta.

- Fragmentariska anteckningar vid Ramlösa helsobrunn (in Swedish). Lund. 1843.

- Kongl. Maj:ts Nådiga Reglemente För förwaltningen af den fond, Kongl. Maj:t af egna medel bahagat anslå till en fattigförsörjnings-anstalt wid Ramlösa hälsobrunn (in Swedish). Lund: Berlingska Boktryckeriet. 1826. OCLC 186080629.

- Ramlösa hälsobrunn 1707-1907: strödda anteckningar ur brunnens historia : utg. till 200-årsjubileet 1907 (in Swedish). Helsingborg: Killbergs bokh. OCLC 186728776.

- Wallis, Curt (1878). Ramlösa: Jernkällor, varmbadhus saltsjöbad vid Öresund (in Swedish). Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & S:r. OCLC 676919572.

External links

- Ramlösa.se – homepage for the Ramlösa park (in Swedish)