Muththal Rowther Tamil deity | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Tamilnadu, Kerala, Malaysia, Singapore | |

| Languages | |

| Tamil • Malayalam | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tamil People, Maravar clan |

The Rowther (anglicised as Irauttar, Rawther, Ravuttar, Ravutta, Ravuthar, Ravuthamar) are originally a Tamil community from the Indian state of Tamil Nadu and Kerala.[1] they were converted to Islam by the preacher Nathar Shah.[2] Even after conversion they retained their caste name. they were elite cavalrymen of the Chola and Pandya kingdoms.[3] They were traditionally a martial clan like the Maravars,[4] and constitute large part of the multi-ethnic Tamil Muslim community.[5] Rowthers have also been found as Tamil polygars, zamindars and chieftains from the 16th to 18th centuries.[6] The traditional homelands of the Rowthers were in the interior of Southern Tamilakam.[7][8][9][10][11][12]

Another theory suggest they are descendants of Turkic people who came in Chola Empire.[13]

Etymology

The name Ravuttar (or Ravutta, Ravuthar, Rowther, Rawther) means king, horseman, or cavalry warrior in the Tamil language and is derived from the word Rājaputra, in the sense of 'prince', 'nobleman', or 'horseman'. D.C. Sircar points out that Ravutta or Rahutta, as a title, means a 'subordinate ruler'.[14] Some scholars claim that the name comes from Rathore, a name common among the Muslim Rajputs of North India.[11] Historically, they are parts of clans traditionally holding positions as rulers and military folk. Ravuta means a high-ranking title King, lord, or feudatory ruling chief.[15]

Rahut or rowt means Warrior and raya means captain.[16] Rāvuttarayan or Rāvuttakartan means high military chief of cavalry.

Demography

Rowthers are largest Muslim community in Tamil Nadu. they found all over Tamil Nadu and in Central and Southern Kerala. Their mother tongue is Tamil.[17] Many of them are familiar with the Perso-Arabic script. They adhere to the principles of Islam, engaging in the study of the Quran and other religious texts in Arabic. Simultaneously, despite their commitment to their Islamic faith, they share a common pride with all Tamils in their rich Tamil language and vibrant cultural heritage.[18]

Culture

Rowthers generally speak Tamil.[19] They have their own distinct culinary traditions which notably include Rowther Biryani.[20][21][22] The elderly men wear white Vēṭṭis or white kayili while elderly women wear a white thupatti draped over a sari.[18][12]

Traditional costumes also include the Fez and a traditional turban called a Thalappakattu. The community also celebrates a festival called Chandanakudam every year.

Titles/surname

Ravuttar, Rawther, and Rowther are common surnames among the group,[23] but other titles often used are below:

- Sahib[24]

- Khan[25]

- Shah

- Pillai/Pillay[26] (Travancore and Tamil Nadu)

- Ambalam and Vijayan[27] (Ramnad Zamindhari estate)

- Servai[28] Servaikkarar (In 1730s, Ravuttan Servaikkarar (Rauten Cheerwegaren) was a high military ranked man in Ramnad kingdom.[29])

Identity and origins

Rowthers are Soldiers, officials, and literati attached to Muslim Court in the Deccan.[30] In described as a Rāuta, Rāutta or Rāvutta derived from Sanskrit Rajaputra and was often assumed by subordinate rulers.[31][32]

Later, Chola kings too invited Horse traders from the Seljuk Empire who belonged to the Hanafi school.[33] During 8th-10th centuries, an armada of Turkish traders settled in Tharangambadi, Nagapattinam, Muthupet, Koothanallur and Podakkudi.[34]

These new settlements were now added to the Rowther community. There are some Anatolian and Safavid inscriptions found in a wide area from Tanjore to Thiruvarur and in many villages. These inscriptions are seized by the Madras museum. Some Turkish inscriptions were also stolen from the Big Mosque of Koothanallur in 1850.[35]

There are two factions of Rowthers in Tamil Nadu, Tamils cavalry warriors covers majority of Tamil Nadu while Seljuk Turkic clans remains in Tharangambadi, Nagapattinam, Muthupet, Koothanallur and Podakkudi.[33] Both now Tamil and Turkish Hanafi expanded with Population and some circumstantial evidence in historical sources that the Rowthers are related to Maravar converts.[36] Rowthers worked in the administration of the Vijayanagar Nayaks.[37]

Social system: kinship

The Rowthers were an endogamous group. But like all modern societies, they have adapted to modern norms and rituals.[38]

Kinship terms

| English | Rowther's Tamil/Malayalam |

| Father | Aththa or Ata/Vaapachi/Vappa |

| Mother | Amma/Buva |

| Elder Brother | Annan |

| Younger Brother | Thambi |

| Elder Sister | Akka |

| Younger Sister | Thangai/Thangachi |

| Paternal grandfather | Atatha/Radha or Thatha |

| Paternal grandmother | Aththamma/Radhima or Thathima |

| Maternal Grandfather | Ayya or Ammatha/Nanna |

| Maternal Grandmother | Ammama/Nannimma |

| Father's elder brother/ Husband of mother's elder sister | Periyatha or Periyavaapa |

| Mother's elder sister / Wife of father's elder brother | Periyamma or Periyabuva |

| Father's younger brother | Chaacha/Chinnaththa |

| Mothers younger sister | Khalamma/Chinnamma/Chiththi |

| Uncle | Mama |

| Aunty | Maami |

| Cousins | Machan & Machi |

| Elder brothers wife | Madhini/Machi |

Rites and rituals

Marriage

Nevertheless, in cities, inter-marriages do occur, although they are rare" (Vines, 1973). Parallel and cross-cousins are potential spouses. they remember their historic valor during their marriage ceremonies, where the bridegroom is conducted in a horseback procession.[8]

Occupational activities

Traditionally the Rowthers were landlords and landowning community (historically mentioned as Rowthers are brave cavaliers and early Muslim horse-traders in Tamil literature[39]) but now they are engaged in various occupations, mostly their own businesses. They deal in gemstones, gold, textiles, and real estate and participate in the restaurant industry, construction work, and general merchandising. Some are professionals, such as doctors, engineers, advocates, and teachers.[40]

Administration and justice

There is no traditional caste council or panchayat as such among the Rowthers. Learned and elderly persons act as advisers. The Rowther have an association that preaches against dowry and collects funds for charity.[40]

Religion and culture

The Rowther belong to the Sunni sect of Islam and the Hanafi school. They follow the five basic tenets of Islam, which are, reciting the Kalima, offering prayer five times a day, observing fast during the month of Ramadan, giving charity (zakah) to the poor, and going on the Haj pilgrimage. The major festivals celebrated are Eid-Ul-Fitr, Chandanakudam and Bakr-id.[40]

Closeness in Tamil inscriptions and literature

The well-known legend of the Shiva saint Manikkavacakar of the 9th century is connected with the purchase of horses for the Pandya king. In that, the god Shiva who appeared in disguise as a horse trader to protect the saint and he is called as Rowther. Also, the Tamil god Murugan is praised by saint Arunagirinathar as சூர் கொன்ற ராவுத்தனே (Oh Ravuttan, who vanquished Sooran) and மாமயிலேரும் ராவுத்தனே (Oh Ravuttan, who rides on the great peacock) in his Kanthar Alangaram (கந்தர் அலங்காரம்) and in Kanthar Venba (கந்தர் வெண்பா).[41][42][43]

This shows the religious harmony of Rowthers and Saivites in early Tamilakam till now.[44][45][46]

There were Tamil Rowthers working in the administration of the Vijayanagara Empire in the Khurram Kunda. The inscription details the dedication of the land by the Rowther to a Murugan temple in Cheyyur.

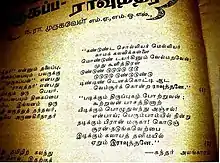

Muththaal Ravuttar (meaning Muslim Rowther is a Prakrit derivation from raja-putra) figures as Tamil male deities who protect Tamil land.[6]

Modernisation

The Rowthers give importance to education. They are one of the most prominent Muslim groups in South India, making their mark in various fields, from jurisprudence to Entertainment.[40]

Notable peoples

See also

References

- ↑ More, J. B. Prashant (1997). The political evolution of Muslims in Tamilnadu and Madras, 1930-1947. Hyderabad, India: Orient Longman. pp. 21–22. ISBN 81-250-1011-4. OCLC 37770527.

- ↑ "Veneration of the prophet Muhammad in an Islamic Pillaittamil. - Free Online Library". www.thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved 18 February 2023.

- ↑ Tschacher, Torsten (2001). Islam in Tamilnadu : varia. Halle (Saale): Institut für Indologie und Südasienwissenschaften der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. pp. 94, 95. ISBN 3-86010-627-9. OCLC 50208020.

- ↑ Hiltebeitel, Alf (1988). The cult of Draupadī. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-226-34045-7. OCLC 16833684.

- ↑ Singh, K. S., ed. (1998). People of India: India's communities. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press. pp. 3001–3002. ISBN 0-19-563354-7. OCLC 40849565.

- 1 2 Hiltebeitel, Alf (1988–1991). The cult of Draupadī. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 13–14, 102. ISBN 0-226-34045-7. OCLC 16833684.

- ↑ More, J. B. Prashant (2004). Muslim Identity, Print Culture, and the Dravidian Factor in Tamil Nadu. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-2632-7.

- 1 2 Rājāmukamatu, Je (2005). Maritime History of the Coromandel Muslims: A Socio-historical Study on the Tamil Muslims 1750-1900. Director of Museums, Government Museum.

- ↑ Jairath, Vinod K. (3 April 2013). Frontiers of Embedded Muslim Communities in India. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-19679-9.

- ↑ Hussein, Asiff (2007). Sarandib: An Ethnological Study of the Muslims of Sri Lanka. Asiff Hussein. ISBN 978-955-97262-2-7.

- 1 2 Bayly, Susan (1989). Saints, goddesses, and kings : Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700-1900. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0-521-37201-1. OCLC 70781802.

- 1 2 "தமிழ் முஸ்லிம்களின் பொங்கல் கொண்டாட்டம் கொண்டிருக்கும் சேதி". அருஞ்சொல். Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ↑ What is Rowther? Explain Rowther, Define Rowther, Meaning of Rowther, archived from the original on 21 December 2021, retrieved 25 March 2021

- ↑ Rao, C. V. Ramachandra (1976). Administration and Society in Medieval Āndhra (A.D. 1038-1538) Under the Later Eastern Gaṅgas and the Sūryavaṁśa Gajapatis. Mānasa Publications. p. 88.

- ↑ Itihas. Director of State Archives, Government of Andhra Pradesh. 1975.

- ↑ The Wars of the Rajas, Being the History of Anantapuram: Written in Telugu; in Or about the Years 1750 - 1810. Translated Into English by Charles Philip Brown. II. Printed at the Christian knowledge society's Press. 1853.

- ↑ SUDHEER, NISHADA (12 September 2021). "THE HISTORY OF RAVUTHERS IN IRINJALAKUDA: LIFE,CULTURE AND HISTORY OF RAVUTHARANGADI" (PDF).

- 1 2 Singh, Ashok Pratap; Kumari, Patiraj (2007). Psychological implications in industrial performance (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Global Vision Pub. House. p. 707. ISBN 978-81-8220-200-9. OCLC 295034951.

- ↑ Parmar, Pooja (20 July 2015). Indigeneity and Legal Pluralism in India: Claims, Histories, Meanings. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-08118-5.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Priyadarshini (23 May 2020). "The Indian Eid feast goes beyond biryani and sevaiyan". mint. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ Jeshi, K. (4 May 2021). "The myriad tastes and cultural influences of iftar". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ A Handbook of Kerala. International School of Dravidian Linguistics. 2000. ISBN 978-81-85692-31-9.

- ↑ Itihas. Director of State Archives, Government of Andhra Pradesh. 1975.

- ↑ Singh, K. S. (1996). Communities, segments, synonyms, surnames and titles. Delhi: Anthropological Survey of India. ISBN 0-19-563357-1. OCLC 35662663.

- ↑ General, India Office of the Registrar (1964). Census of India, 1961: Pondicherry state. Manager of Publications. p. 12.

- ↑ Many Rawthers in erstwhile Travancore used the title "Pillai/Pillay" in south kerala, A Handbook of Kerala. International School of Dravidian Linguistics. 2000. ISBN 978-81-85692-31-9.

- ↑ Kamāl, Es Em (1990). Muslīmkaḷum Tamil̲akamum (in Tamil). Islāmiya Āyvu Paṇpāṭu Maiyam.

- ↑ Proceedings. Indian History Congress. 2000.

- ↑ The Heirs of Vijayanagara Court Politics in Early-Modern South India Author ; Lennart Bes

- ↑ Richman, Paula (1 October 1997). Extraordinary Child: Poems from a South Indian Devotional Genre. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1063-4.

- ↑ Indian Studies. Ramakrishna Maitra. 1967.

- ↑ Aiyangar, Sakkottai Krishnaswami (1921). South India and her Muhammadan Invaders. Oxford University Press. pp. 95–96.

- 1 2 Abraham, George (28 December 2020). Lanterns on the Lanes: Lit for Life…. Notion Press. ISBN 978-1-64899-659-7.

- ↑ Fragner, Bert G.; Kauz, Ralph; Ptak, Roderich; Schottenhammer, Angela (2009). Pferde in Asian : Geschichte, Handel und Kultur [Horses in Asia : history, trade, and culture]. Wien. pp. 150–160. ISBN 978-3-7001-6638-2. OCLC 1111579097.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Arunachalam, S. (2011). The history of the pearl fishery of the Tamil coast. Pavai Publications. p. 96. ISBN 978-81-7735-656-4. OCLC 793080699.

- ↑ Tschacher, Torsten (2001). Islam in Tamilnadu : varia. Halle (Saale): Institut für Indologie und Südasienwissenschaften der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. p. 99. ISBN 3-86010-627-9. OCLC 50208020.

- ↑ Muthiah, S., ed. (2008). Madras, Chennai : a 400-year record of the first city of modern India (1st ed.). Chennai: Palaniappa Brothers. p. 140. ISBN 978-81-8379-468-8. OCLC 419265511.

- ↑ Kumari, Ashok Pratap Singh& Patiraj (2007). Psychological Implications in Industrial Performance. Global Vision Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-8220-200-9.

- ↑ Special Volume on Conservation of Stone Objects. Commissioner of Museums, Government Museum. 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 Singh, Ashok Pratap; Kumari, Patiraj (2007). Psychological implications in industrial performance (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Global Vision Pub. House. p. 708. ISBN 978-81-8220-200-9. OCLC 295034951.

- ↑ "மயிலேறும் இராவுத்தன்". Hindu Tamil Thisai (in Tamil). 2 July 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ கமால், எஸ் எம். "முஸ்லீம்களும் தமிழகமும்/ராவுத்தர் - விக்கிமூலம்". ta.wikisource.org (in Tamil). Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ↑ Muthiah, S. (2008). Madras, Chennai: a 400-year record of the first city of modern India (1st ed.). Chennai: Palaniappa Brothers. p. 140. ISBN 978-81-8379-468-8. OCLC 419265511.

- ↑ Rājāmukamatu, Je (2005). Maritime History of the Coromandel Muslims: A Socio-historical Study on the Tamil Muslims 1750-1900. Director of Museums, Government Museum.

- ↑ Cōmale (1980). Maturai Māvaṭṭam (in Tamil). Kastūrpā Kānti Kan̲yā Kurukulam, Veḷiyīṭṭup Pakuti.

- ↑ Anwar, Kombai S. (7 June 2018). "A secular temple in Kongu heartland". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

Bibliography

- J. P. Mulliner. Rise of Islam in India. University of Leeds chpt. 9. Page 215

- Hussein, Asiff (2007). Sarandib : an ethnological study of the Muslims of Sri Lanka (1st ed.). Nugegoda: Asiff Hussein. ISBN 978-955-97262-2-7. OCLC 132681713.

- Singh, K. S.; Thirumalai, R.; Manoharan, S., eds. (1997). People of India. Tamil Nadu. Madras: Affiliated East-West Press [for] Anthropological Survey of India. pp. 1259–1262. ISBN 81-85938-88-1. OCLC 48502905.

- Singh, K. S.; Madhava Menon, T.; Tyagi, D.; Kulirani, B. Francis, eds. (2002). Kerala. New Delhi: Affiliated East-West Press [for] Anthropological Survey of India. p. 1306. ISBN 81-85938-99-7. OCLC 50814919.

- Mines, Mattison. Social Stratification among the Muslim Tamils in Tamil Nadu, South India, Imtiaz Ahmad, ed, Caste, and Social Stratification among the Muslims, Manohar book service, New Delhi, 1973.

- Nanjundayya, H.V. and lyer, LK.A, 1931, The Mysore Tribes and Castes, IV, The Mysore University. Mysore.

- Thurston, E., Castes and Tribes of Southern India, Government Press, Madras, 1909.