| Pacific herring | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Clupeiformes |

| Family: | Clupeidae |

| Genus: | Clupea |

| Species: | C. pallasii |

| Binomial name | |

| Clupea pallasii Valenciennes in Cuvier and Valenciennes, 1847 | |

| |

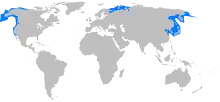

The Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii) is a species of the herring family associated with the Pacific Ocean environment of North America and northeast Asia. It is a silvery fish with unspined fins and a deeply forked caudal fin. The distribution is widely along the California coast from Baja California north to Alaska and the Bering Sea; in Asia the distribution is south to Japan, Korea, and China. Clupea pallasii is considered a keystone species because of its very high productivity and interactions with many predators and prey. Pacific herring spawn in variable seasons, but often in the early part of the year in intertidal and sub-tidal environments, commonly on eelgrass, seaweed[1] or other submerged vegetation; however, they do not die after spawning, but can breed in successive years. According to government sources, the Pacific herring fishery collapsed in the year 1993, and is slowly recovering to commercial viability in several North American stock areas.[2] The species is named for Peter Simon Pallas, a noted German naturalist and explorer.

There are disjunct populations of Clupea pallasii in North-East Europe, which are often attributed to separate subspecies Clupea pallasii marisalbi (White Sea herring) and Clupea pallasii suworowi (Chosha herring).

Morphology

Pacific herring have a bluish-green back and silver-white sides and bellies; they are otherwise unmarked. The silvery color derives from guanine crystals embedded in their laterals, leading to an effective camouflage phenomenon. There is a single dorsal fin located mid-body and a deeply forked tail-fin. Their bodies are compressed laterally, and ventral scales protrude in a somewhat serrated fashion. Unlike other genus members, they have no scales on heads or gills;[3] moreover, their scales are large and easy to extract. This species of fish may attain a length of 45 centimeters in exceptional cases and weigh up to 550 grams, but a typical adult size is closer to 33 centimeters. The fish interior is quite bony with oily flesh.

This species has no teeth on the jawline, but some are exhibited on the vomer. Pacific herring have an unusual retinal morphology that allows filter feeding in extremely dim lighting environments. This species is capable of rapid vertical motion, due to the existence of a complex nerve receptor system design that connects to the gas bladder.[4]

Life cycle

Pacific herring prefer spawning locations in sheltered bays and estuaries. Along the American Pacific Coast, some of the principal areas are San Francisco Bay, Richardson Bay, Tomales Bay and Humboldt Bay. Adult males and females make their way from the open ocean to bays and coves around November or December, although in the far north of the range, these dates may be somewhat later. Conditions that trigger spawning are not altogether clear, but after spending weeks congregating in the deeper channels, both males and females will begin to enter shallower inter-tidal or sub-tidal waters. Submerged vegetation, especially eelgrass, is a preferred substrate for oviposition. A single female may lay as many as 20,000 eggs in one spawn following ventral contact with submerged substrates. However, the juvenile survival rate is only about one resultant adult per ten thousand eggs, due to high predation by numerous other species.

The precise staging of spawning is not understood, although some researchers suggest the male initiates the process by release of milt, which has a pheromone that stimulates the female to begin oviposition. The behavior seems to be collective so that an entire school may spawn in the period of a few hours, producing an egg density of up to 6,000,000 eggs per square meter.[5] The fertilized spherical eggs, measuring 1.2 to 1.5 millimeters in diameter, incubate for approximately ten days in estuarine waters that are about 10 degrees Celsius. Eggs and juveniles are subject to heavy predation.

Fisheries

Pacific herring fisheries (fishing grounds) had been sustainably exploited by indigenous people for millennia, not only in the Pacific Coasts of North America, but in Japan, and Russian Far East, and in all these cases, industrial fishing for herring oil and fertilizer encroached or seized these fishing areas, leading to collapses in the fish stock.[7]

The Ainu of Ezo (now Hokkaido) had caught herring using basic dip nets (hand nets)[lower-alpha 1] but Japanese fishermen during the late Edo Period into Meiji Era began to operate increasingly large-scaled capture of herring in these grounds, first using gillnets and later "pound nets" (or traps).[8][9][11] Intensive fishing resulted in the so-called "Million-Ton Era" of the late nineteenth century onward,[13] Herring fishery near Japan (Hokkaido) collapsed in the late 1950s.[8][14]

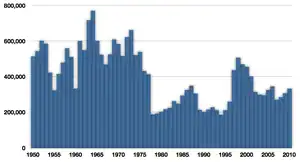

Much like Japan, commercial herring fisheries in Alaska, US, and British Columbia underwent the phase of § Reduction fishery (for fertilizer and oil), and when Japanese herring fleets suffered scarcity in the late 1950s, North American fisheries began to cater to the Japanese market especially for the herring roe (§ Roe fishery; § Spawn on kelp fishery), known in Japan as § kazunoko. Alaska Department of Fish and Game has managed Alaskan resources and issues quota has released their biomass estimate figures since 1975, but the figures remain highly volatile.[15]

Herring has long been fished by First Nations on the Central Coast of British Columbia, and elsewhere. In 1997 the Supreme Court of Canada rendered its decision in the Gladstone decision (R. v. Gladstone)- recognizing a pre-existing aboriginal right to herring that includes a commercial component to the Heiltsuk Nation.

Due to overfishing,[16] the total North American Pacific herring fishery collapsed in 1993, and is slowly recovering with active management by North American resource managers. In various sub-areas the Pacific herring fishery collapsed at slightly differing times; for example, the Pacific herring fishery in Richardson Bay collapsed in 1983.[17] The species has been re-appearing in harvestable numbers in a number of North American fisheries including San Francisco Bay, Richardson Bay, Tomales Bay, Half Moon Bay, Humboldt Bay all in California, and Sitka Sound, Alaska. In other areas, such as Auke Bay, Alaska, which in the late 1970s was the largest harvestable stock of herring in Alaska, the species remains severely depleted.[18]

Pacific herring are currently harvested commercially for bait and for roe. Past commercial uses included fish oil and fish meal.[18]

Reduction fishery

The Alaskan herring industry began in 1880s as "reduction" plants which processed herrings into fish meal and oil, with the meal utilized mostly as animal fodder or fertilizer,[19] and the oil mostly for soap.[20] Since it began the reduction in 1882 until around 1917, the business was a practical monopoly of the North West Trading Company which established its processing plant at Killisnoo, Alaska.[21] The use of "Norwegian method" of catching using oar-propelled seine boats did continue until 1923 here, but was being supplanted by the purse seine (purse seiner) introduced into herring fishery around after 1900.[22]

Concerns had developed regarding this practice as early as the 1900s, regarding localized fish stock depletion, adverse food chain effects on commercially valuable fish types that prey on herring, and the ethics of taking fish for purposes other than human food or bait,[23] But the industry persisted in Alaska until it ceased operations in 1966.[24]

In Canada, the earliest recorded catches were for the purpose of producing dry-salted herring, starting around 1904, peaking around the 1920s,[lower-alpha 2] but declining to initial catch tonnages by 1934 due to sagging demand.[25] Reduction (fertilizer) fishing operated in Canada during the years 1935–1967. The end was due to the collapse of the fish population.[25]

Roe fishery

Just as the reduction industry was phasing out in Alaska in the 1960s, there emerged an alternate industry to exploit herring in another way, i.e., harvesting only the "roe sacs" ("egg skein") inside the females, to meet the Japanese demand for "kazunoko".[lower-alpha 3][24] A similar shift took from the defunct reduction fishing took place in Canada: after the herring population recovered somewhat, a Canadian roe fishery industry sprang up in 1971 to cater to the Japanese market.[29][lower-alpha 4]).

A commercially viable product demands the eggs to be "ripe", or swollen to the right size, which only occurs within a few days of spawning, and there is a narrow window for the catch.[29][33] Accordingly, the season is very short, a matter of days: it lasted all of 90 minutes in the April 1975 season.[33][34]

These egg skeins need to retain perfection of shape to fetch highest value, and to that end, the fish are frozen or brine-frozen then rethawed in freshwater before extracting the egg skeins.[34]

Spawn on kelp fishery

Shoals of herring during the reproductive season lay clusters of eggs on kelp and other seaweed,[lower-alpha 5][lower-alpha 6] and the seasonal collection has been a time-honored traditional practice among the natives of Pacific Coast of Alaska and Canada,[38][39] witnessed and recorded in the 18th and 19th centuries,[43] and has been traded [38] and a trade item.[41] The natives traditionally foraged wild-grown eggs on various seaweed, or laid on introduced hemlock branches,[42][44].

The Japanese market for kazunoko kombu (数の子コンブ, 'herring roe kelp') or (子持ちコンブ, 'child holding kelp') is best served, so it has been claimed, by preferably using products laid on giant kelp (Macrocystis pyrifera), which only grew in Southeast Alaska [45][lower-alpha 7] or down in Canada.[lower-alpha 8][lower-alpha 9]

[lower-alpha 10] commercial harvest of wild-caught roe began in that region at Craig/ Craig/ Klawock [lower-alpha 11], in 1959[lower-alpha 12][51] Export to Japan began 1962.[lower-alpha 13] So that in wild foraging surged at Craig/Klawock 1963, burgeoned in Sitka in 1964, and at a third site at Hydaburg in 1966 were harvesting in southeast Alaska:[52] overfilling their 250 tons quota in 1966.[54] The season had to be drastically shortened or canceled due to depletion from the following year.[55]

- (Transplanting and impounding kelp)

And in 1960 and 1961 "open-pounds", stocked with kelp to lure herring egg-laying, were operated in the town of Craig, on Prince of Wales Island, probably for the first time in Alaska.[52] But afterwards, intensified harvest led to closure of season, and it was not until 1992 that harvest of semi-farmed eggs on kelp in closed-pounds resumed.[56]

The shortage of spawn led to seeking new harvesting grounds in areas where giant kelp do not naturally grow, and demand and harvest developed for eggs on alternate seaweeds, such as Desmarestia sp. or "hair seaweed".[lower-alpha 5][56] Amidst the 1968 shortage, commercial collection of spawn of Fucus began,[lower-alpha 6] in Bristol Bay, east of Togiak.[57] And in 1959 spawn from various algae began to be commercially collect from Prince William Sound, peaking in 1975, ending with the depletion of the "kelp".[57][lower-alpha 9]

During the shortage, an enterprising operator experimented with transplanting "unused" kelp from remoter areas into kelp-depleted spawning grounds, or into eelgrass territory. He sometimes attached kelp cut elsewhere to barges he owned.[53]

In Canada, "impoundments" began to be used, whereby floating enclosures at sea are stocked with kelp, mature herring are introduced, and the egg-deposited kelp to be later harvest. Canada issued their first licenses in 1975, initially about half to indigenous operators, in Northern British Columbia.[29] The enclosure ("closed pounds") technique was subsequently copied by Alaskans.[58] The "impoundments" or "closed ponds" consisted of a square (wooden) frame holding a pocket of "suspended webbing" as enclosure space. Inside, rows of kelp are hung on strings. [29][58][60]

Decline

Alaska's principal areas for roe fishery, according to the 2022 season allotted tonnage were: Sitka Sound (late March) 45,164 short tons (90,000,000 lb), Kodiak Island (April 1) 8,075 short tons (16,000,000 lb), and Togiak[lower-alpha 14] (May) 65,107 short tons (130,000,000 lb). However the allowed quotas were hardly expected to be filled, given the drastic downturn in Japanese demand. During the heydays of the 1990s, the pre-spawn herring commanded $1000 per ton, yielding a gross $60 million to fisherman, but by 2020 the tally fell to a $5 million figure.[62] In 2023, the last roe processing plant in Togiak indicated it would not be purchasing herring, and the season was cancelled.[63]

Conservation

On April 2, 2007, the Juneau group of the Sierra Club submitted a petition to list Pacific herring in the Lynn Canal, Alaska, area as a threatened or endangered distinct population segment under the criteria of the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA).[64] On April 11, 2008, that petition was denied because the Lynn Canal population was not found to qualify as a distinct population segment. However, the National Marine Fisheries Service did announce would be initiating a status review for a wider Southeast Alaska distinct population segment of Pacific herring that includes the Lynn Canal population.[65] The Southeast Alaska DPS of Pacific herring extends from Dixon Entrance northward to Cape Fairweather and Icy Point and includes all Pacific herring stocks in Southeast Alaska.

On February 5, 2018, researchers at Western Washington University began researching causes for the decline in Pacific herring populations in the Puget Sound; a prominent speculated reason is the loss of eelgrass, an important spawning substrate for the herring.[66]

Kazunoko

The herring egg roe or "egg skein", called kazunoko had traditionally commanded a good price in Japanese markets, and the herring roe fishery and processing industry (especially in Alaska), geared towards export to that country, has been described above under § Roe fishery.

As for the culinary aspects, the kazunoko merchandized in Japan primarily fall into either hoshi kazunoko (塩数の子, 'dried kazunko') or shio kazunoko (干し数の子, 'dried kazunko').[67] There is also a lower-grade substitute[70] called shio kazunoko (味付け数の子, 'dried kazunko'),[31] made from Atlantic herring roe (which is considered a softer or "less crunchy" in texture).[31][32][68] [lower-alpha 15]

The roe is eaten mostly as the New Year's fare,[71] called osechi, consisting of an assortment of symbolically propitious foods, with herring representing fertility (production of many children).[72][73]

- ↑ And possibly, seine nets.

- ↑ The initial catch tonnage was at around 30,000t per year. Introduction purse seine to Canadian herring fishing occurred in 1913, but the catch tonnage remained flat for some years until it rose to 85,000 tons in 1919–1927.

- ↑ Small-scale roe fishery about 1 ton operated in Alaska in 1961 and 1963 at Resurrection Bay and lower Cook Inlet, but more serious operations commenced in 1964 in Sitka at Sitka Sound, Spiridon Bay on Kodiak Island, and Unalakleet (Norton Sound),[26] In Togiak, roe fishery began experimentally in 1967 but greatly expanded 1977 onward to become the major site of the roe fishery haul.[27][28]

- ↑ After Alaska, various other regions began competing for the market: California, British Columbia (Canada), eastern Canada, Russia, South Korea, China, Scotland (UK), Ireland, Netherlands.[30] Eastern Canadian and European fisheries of course harvest Atlantic herring roe, which is considered a softer (less crunchy), and are processed as "flavored kazunoko (ajitsuke kazunoko)" which are surrogates for standard "salted kazunoko.[31][32] (More details under § Kazunoko below

- 1 2 Even if not strictly "kelp" (large members of order Laminariales), the seaweed may still be called a type of "kelp" by locals or the local industry, thus Desmarestia aka "hair kelp" according to Mackviak[35] and some Alaska DFS writers,[36] though a paper form other researchers of the Department dated later refer use "hair seaweed" identified as Desmarestia viridis,[37] though in the local vocabulary list they gloss Tlingit ne} as "hair kelp" [37]

- 1 2 Another egg host algae, Fucus sp., is called "rockweed",[35][36] and is not strictly "kelp" either (also different ordo), but the collectors are still called "kelpers" an the product "roe on kelp", even if Fucus is mainly targeted in Bristol Bay.[36]

- ↑ e.g. Hydaburg,[42] Prince Wales Island and Sitka described below.

- ↑ However, the premium kombu kelp of Japanese cuisine derives from makombu, now listed as Saccharina latissima but formerly known as Laminaria saccharina, common name "sugar wrack", surveyed as growing in Prince William Sound.[46]

- 1 2 The statement that at Prince William Sound "ribbon kelp (Laminaria sp.) was the most desirable native species"[42] is problematic, since Laminaria could conceivably refer to the aforementioned Japanese true kombu or "sugar wrack", whereas "ribbon kelp" is a common name for two other alga, namely Nereocystis luetkeana aka "bull kelp" and Alaria marginata,[47] but herring do not lay egg on "bull kelp"[48] while the latter was explained by Charles F. Newcombe (1901) as occasionally harvested with spawn and eaten by the Haida.[49]

- ↑ After Japanese expressed interest in Alaskan herring roe and egg on kelp in 1958 as alternate sourcing.[50]

- ↑ On Prince of Wales Island, neighboring Canada.

- ↑ 107,900 pounds (48,942.617 kg) were collected using grappling hooks.

- ↑ According to federal statistics at the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries. The Japanese presumably approached Alaskans in 1958 seeking herring roe. As to who the buyers were in the meanwhile before 1962, there is an anecdote of a Japanese-American Harry Yoshimura's family proprietorship making a purchase.[45]

- ↑ Both purse seiners and gillnetting are involved.[61][28]

- ↑ Atlantic roe is otherwise made into processed foods[32] or sōzai (惣菜, 'side dishes')[69]

References

- Citations

- ↑ Herring Spawn on Kelp Photo Archived 2014-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Alaska Fisheries 1998 study Archived 2006-10-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Roger A. Barnhart, Species Profile: Life Histories and Environmental Requirements of Coastal Fishes and Invertebrates (Pacific Southwest): Pacific Herring, pp. 1–8, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, February, 1988

- ↑ J.H.S. Blaxter, The Herring: a Successful Fish?, Journal of Canadian Journal of Fish. Aquatic Sci.(suppl. 1) 42:21-30 (1985)

- ↑ J.D. Spratt, The Pacific herring resource of San Francisco and Tomales Bays: Its size and structure, California Department of Fish and Game Marine Research Tech. 33, 44p (1976)

- ↑ Clupea pallasii (Valenciennes, 1847) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- ↑ Thornton & Moss (2021), p. 30.

- 1 2 Thornton & Moss (2021), p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Yokoyama, Satoshi [in Japanese] (2013). Seaweeds: Edible, Available, and Sustainable 資源と生業の地理学. Kaiseisha press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 9784860992743.} (in Japanese)

- ↑ "Japanese Fishery". The Japan Magazine. 2 (3): 147. July 1911., cont. August 1911,Fishery (II)", pp. 228–232

- ↑ Yokoyama provides illustrated comparison of Fig. 4b sashiami or gillnets with two types of pound nets, 4c Yukitsuna ami introduced 1847/c. 1850 (almost End of Edo) and 4d kaku ami c. 1885/1890 (mid-Meiji).[9][10]

- ↑ Cf. Imada, Mitsuo (1991) Nishin gyoka retsuden: hyakumangoku jidai no ninaite tachi ニシン漁家列伝-百万石時代の担い手たち, cited by Yokoyama (2013), p. 133

- ↑ Referred to as "Million koku era" in Japanese literature,[12] measuring the catch by traditional volume measure.

- ↑ Or decade of the "Showa 30s" (1955~).[9]

- ↑ Hebert, KP (2011). "Scuba Diving Surveys Used to Estimate Pacific Herring Egg Deposition in Southeastern Alaska". In: Pollock NW, ed. Diving for Science 2011. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences 30th Symposium. Dauphin Island, AL: AAUS; 2011. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Dean, Cornelia (3 November 2006). "Study Sees 'Global Collapse' of Fish Species". New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ↑ Patrick Sullivan, Gary Deghi and C. Michael Hogan, Harbor Seal Study for Strawberry Spit, Marin County, California, Earth Metrics file reference 10323, BCDC and County of Marin, January 23, 1989

- 1 2 O'Clair, Rita M. and O'Clair, Charles E., "Pacific herring," Southeast Alaska's Rocky Shores: Animals. pg. 343-346. Plant Press: Auke Bay, Alaska (1998). ISBN 0-9664245-0-6

- ↑ Mackovjak (2022), p. 19.

- ↑ Mackovjak (2022), pp. 19, 25.

- ↑ Mackovjak (2022), pp. 21–24.

- ↑ Rounsefell (1935), p. 19.

- ↑ Mackovjak (2022), pp. 19–20.

- 1 2 Mackovjak (2022), p. 20.

- 1 2 Hourston & Haegele (1980), pp. 6.

- ↑ Mackovjak (2022), pp. 146, 153.

- ↑ Mackovjak (2022), pp. 224, 229.

- 1 2 Wright & Chythlook (1985), p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 Hourston & Haegele (1980), pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Mackovjak (2022), p. 144.

- 1 2 3 4 Alaska Sea Grant College Program (2001). Funk, Fritz (ed.). Herring: Expectations for a New Millennium : Proceedings of the Symposium Herring 2000, Expectations for a New Millennium, Anchorage, Alaska, USA, February 23-26, 2000. University of Alaska Sea Grant College Program. p. 725.

Atlantic herring roe, which is generally smaller and softer than Pacific herring roe, has never been considered suitable for salted kazunoko. But seeking a substitute for high-priced Pacific roe in the 1980s, processors tried Atlantic roe for flavored kazunoko, and found it acceptable.

- 1 2 3 Tomoko, Furukawa (2005). "kazunoko" 数の子 [Pacific herring ovary]. Shokuzai kenkō daijiten 食材健康大事典 (in Japanese). Gomyō, Toshiharu (supervising editor). Tübingen: [[[Jiji Press]]. p. 345. ISBN 9784788705616.

- 1 2 Mackovjak (2022), p. 148.

- 1 2 Bledsoe, Gleyn; Rasco, Barbara (2006). "Ch. 161. Caviar and Fish Roe". In Hui, Yiu H. (ed.). Handbook of Food Science, Technology, and Engineering. CRC Press. p. 161-11. ISBN 978-0-8493-9849-0.

- 1 2 Mackovjak (2022), p. 273.

- 1 2 3 Blackburn, James E.; Jackson, Peter B. (April 1982), Seasonal Composition and Abundance of Juvenile and Adult Marine Finfish and Crab Species in the Nearshore Zone of Kodiak Island's Eastside during April 1978 through March 1979, p. 412 in Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program, Final Report of Principal Investigators, Vol. 54, February 1987, Anchorage, Alaska: US Dept. Comm.

- 1 2 Schroeder & Kookesh (1990), pp. 2, 7.

- 1 2 Mackovjak (2022), p. 15–17.

- ↑ Hourston & Haegele (1980), p. 7.

- ↑ Schroeder & Kookesh (1990), p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Schroeder & Kookesh (1990), p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Mackovjak (2022), p. 15.

- ↑ Quoted from Étienne Marchand, the Solide expedition of 1790–92;[40] from Aurel Krause visit on April 25, 1882 (1881–82 expedition);[41] and Jefferson Franklin Moser[41][42]

- ↑ Schroeder & Kookesh (1990), pp. 6–7, 18–22.

- 1 2 Mackovjak (2022), p. 275.

- ↑ Exxon (1991). "Sugar Wrack (Laminaria saccharina)". A Field Guide to Prince William Sound. Exxon Company U.S.A., Arctic Environmental Information and Data Center (Alaska). pp. 6, 7.

- ↑ Mouritsen, Ole G. [in Danish] (2013). Seaweeds: Edible, Available, and Sustainable. Translated by Johansen, Mariela. photography by Jonas Drotner Mouritsen. University of Chicago Press. p. 250. ISBN 9780226044538.}

- ↑ Springer, Yuri; Hays, Cynthia; Carr, Mark; Mackey, Megan (1 March 2007), Ecology and Management of the Bull Kelp Nereocystis luetkeana: A Synthesis with Recommendations for Future Research (PDF), With assistance from Ms. Jennifer Bloeser, Ecological Management of Kelp Forests in Oregon and Washington, p. 30, citing Dr. Michael S. Stekoll, persona communication, 2006

- ↑ Turner (2004), p. 199.

- ↑ Mackovjak (2022), p. 274.

- ↑ Mackovjak (2022), pp. 273–275.

- 1 2 3 Mackovjak (2022), p. 276.

- 1 2 Mackovjak (2022), pp. 277–279.

- ↑ Alaska Department of Fish and Game set quotas of 100 and 75t each for the others, respectively,[52] and total 274 tons (trimmed weight) was reported for 1966, valued at $600,000, for an open season the lasted only an hour or hour-and-a-half.[53]

- ↑ Mackovjak (2022), pp. 279–280.

- 1 2 Mackovjak (2022), p. 279.

- 1 2 Mackovjak (2022), p. 280.

- 1 2 Mackovjak (2022), pp. 281.

- ↑ Woodford, Riley (May 2020). "Record Herring Event Highlights Roe on Kelp Fishery". Alaska Fish & Wildlife News. Alaska Department of Fish and Game.

- ↑ Cf. Alaska DFG article with photographs.[59]

- ↑ Mackovjak (2022), pp. 219–237.

- ↑ Welch, Laine (28 March 2022). "As demand for Alaska herring roe plummets, industry seeks markets for the wasted fish". Alaska Dispatch News.

- ↑ Ross, Izzy Ross (26 March 2023). "No commercial Togiak sac roe herring fishery this spring, after years of a shrinking market". KDLG. Dillingham.

- ↑ "Endangered Species Act". 16 January 2023.

- ↑ Announcement of initiation of status review for Southeast Alaska Pacific herring

- ↑ "New Puget Sound herring research". Puget Sound Institute. 2018-02-05. Retrieved 2019-09-01.

- ↑ OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2009). "Kazunoko". Multilingual Dictionary of Fish and Fish Products. John Wiley & Sons. p. 532. ISBN 9781444319422.

- 1 2 "Herring". Seafood Leader. 9 (4): 142. April 1989.

The Japanese used to purchase only roe from Pacific.. insurgence of the European herring stocks has led to a secondary market in Atlantic roe.. Atlantic herring roe is generally less crunchy and tangy than Pacific herring roe and so sells for less

- 1 2 JETRO (1991). Nōrin suisanbutsu no bōeki: shuyō 100 hinmoku no kokunai・kaigai jijyō 農林水産物の貿昜: 主要 100品目の国内・海外事情 (in Japanese). Japan External Trade Organization. pp. 480, 567.

主として味付けかずのこの原料として利用されるにしんの卵は大西洋産、正月の贈答用などに用いられるにしん卵等は太平洋産である

- ↑ lower grade, as per "substitute",[31] "secondary market",[68] and the remark that only the Pacific herring roe is considered suitable for New Year's gift-giving in Japan.[69]

- ↑ Emami, Ali; Queirolob, Lewis E.; Johnston, Richard (1994), "Monopsony, Trade Restrictions and International Markets for Intermediate Seafood Products. The U.S.-Canada Herring Dispute", in Antona, Martine; Cantanzano, Joseph; Sutinen, John G. (eds.), Proceedings of the Sixth Conference of the International Institute of Fisheries Economics and Trade (PDF), vol. 2, Institut français de recherche pour l'exploitation de la mer, p. 590 n1

- ↑ Andreasen, Esben; Rasco, Barbara (1998). Popular Buddhism in Japan: Shin Buddhist Religion and Culture. University of Hawaii Press. p. 170. ISBN 9780824820282. Citing Hazama, D. O.; Komeiji, J. O. (1986) Okage sama De", pp. 263–5

- ↑ Mouritsen, Ole G. [in Danish]; Styrbæk, Klavs (2023). Rogn: Meget mere end rogn. Gyldendal A/S. § Frugtbarhed og mange børn. ISBN 9788702392029. (in Danish)

- Bibliography

- Hourston, A. S.; Haegele, C. W. (1980), Herring on Canada's Pacific Coast (PDF), Ottawa: Canadian Special Publications of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, Department of Fisheries and Oceans

- Mackovjak, James (2022). "Chapter 1. Alaska Herring, The Basics; Chapter 9. Genesis and Management of Alaska's Ro-Herring Fishery". Alaska Herring History: The Story of Alaska’s Herring Fisheries and Industry. University of Alaska Press. ISBN 9781646423439.

- Rounsefell, George A. (1935). "Fluctuation in the Supply of Herring (Culpea pallasii) in Southeastern Alaska". Bulletin of the Bureau of Fisheries. 47: 15–56.

Schroeder, Robert F.; Kookesh, Matthew (January 1990), The Subsistence Harvest of Herring Eggs in Sitka Sound, 1989 (PDF), Technical Paper No. 173, Alaska Department of Fish and Game

- Thornton, Thomas F.; Moss, Madonna L. (2021), Herring and People of the North Pacific: Sustaining a Keystone Species, University of Washington Press, ISBN 9780295748306

- Turner, Nancy J. (2004), Plants of Haida Gwaii, Illustrated by Florence Edenshaw Davidson, Winlaw, B.C.: Sono Nis Press, ISBN 1-55039-144-5

- Wright, John M.; Chythlook, Molly B. (March 1985), Subsistence harvest of herring spawn-on-kelp in the Togiak District of Bristol Bay (PDF), Technical Paper No. 116, Juneau, Alaska: Alaska Department of Fish and Game

External links

- The Hakai Herring School website

- Alaska Fish and Game species writeup

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service species profile: Pacific herring

- Abundance, age, sex, and size statistics for Pacific herring in the Togiak district of Bristol Bay, 2004 by Chuck Brazil. Hosted by the Alaska State Publications Program.

- Kodiak management area herring sac roe fishery harvest strategy for the 2007 season / by Jeff Wadle, Geoff Spalinger, and Joe Dinnocenzo. Hosted by the Alaska State Publications Program.