Mallam Sa'adu Zungur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Ahmed Mahmud Sa'ad Zungur 1914 |

| Died | 28 January 1958 |

| Nationality | Nigerian |

| Occupations |

|

| Political party | Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU) |

| Other political affiliations | |

Philosophy career | |

Main interests | |

Sa'adu Zungur (1914 – 28 January 1958) was a Nigerian revolutionary, poet, jurist and nationalist who played an important role in Nigeria's independence movement particularly in Northern Nigeria. He is generally regarded as the father of 'radical politics' in Northern Nigeria.[1] Zungur's political writings criticising the colonial government of Northern Nigeria, especially the emirate system, helped in laying the foundation for the principle of self-determination in Nigeria. His literary and political endeavors influenced a number of the leaders of the independence movement in Northern Nigeria, notably Aminu Kano and Isa Wali.[2][3][4][5]

Zungur also founded a number of political organisations, including the Zaria Friendly Society and Northern Elements Progressive Association, which later played an important role in shaping the region's political landscape and later influenced the establishment of subsequent political parties and movements. At various times in the late 1940s and 1950s, he was active in other prominent political parties like the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons, the Northern People's Congress and the Northern Elements Progressive Union.[6]

Despite his prolonged battle with a lung disorder, which spanned nearly two decades, Zungur remained active in the fight for Nigeria's independence and its societal reform. His dedication and contributions earned him recognition as a prominent figure in the struggle for social justice and self-governance. He passed away in 1958, just two years before Nigeria achieved independence.[6][7] The Sa’adu Zungur University (formerly Bauchi State University, Gadau) is named after him.[8]

Early life and education

Zungur was born in 1914 in Ganjuwa, Bauchi province (modern-day Bauchi state) to then Imam of Bauchi Muhammadu Bello.[4] He grew up in a household that placed strong emphasis on religious teachings. He commenced his Islamic education at a young age and progressed to studying more advanced aspects of Islam, such as fiqh (Islamic jurispudence).[6]

Despite his religious upbringing, his father also encouraged him to pursue a western education, a rarity in 1920s colonial Northern Nigeria. In 1920, he was enrolled in Bauchi Provincial School, and in 1929, he furthered his education at Katsina Higher College (now known as Barewa College), which was one of the pioneering college institutions in Northern Nigeria.[2][3][6]

At the age of 20, he enrolled in the newly established Yaba Higher College in Lagos as the first government sponsored Northerner to study outside of the North. He also became the first Northerner to study Pharmacy. Zungur desired to study Chemistry and Biology at Yaba but was refused. This lead him to discontinue his studies at the college and in 1935, was posted to School of Hygiene in Kano (now College of Health Science and Technology) as punishment. During his time in Kano, Zungur initially trained as a Class Sanitary Inspector. However, shortly after beginning this training, he was promoted to the role of a Teacher within a month.[6]

Career

In 1939, Zungur was transferred to School of Hygiene in Zaria where he continued to teach. In the same year he established the Hausa Youth Keep Fit Class, a class for youth around Zaria on physical fitness.[9] While in Zaria, he met Aminu Kano who was studying at Kaduna College. Their connection evolved into a deep friendship, marked by frequent discussions about political matters and concerns that were relevant to Northern Nigeria. During this time, Zungur was said to have "influenced Aminu's thinking profoundly." By 1941, Zungur had assumed the position of head of the School of Pharmacy in Zaria. In the following year, he founded the Northern Nigeria Youth Movement (NNYM), which eventually evolved into the Zaria Friendly Society (ZFS) or Taron Masu Zunuta, with Abubakar Imam, a prominent writer who was the editor of the Gaskiya Ta Fi Kwabo newspaper. The association was a platform which Zungur used to agitate for social reforms and to educate and enlighten the people of Northern Nigeria on political issues.[10] He also founded the Northern Provinces General Improvement Union (NPGIU) during the time. He was later stricken with a lung disorder (possibly tuberculosis) which led to take a break from teaching and to return to his home in Bauchi to rest.[3][6][11]: 72–74

Politics

While at Bauchi, Zungur together with Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, Aminu Kano and some Northern elites formed the Bauchi General Improvement Union (BGIU), one of the first political organisations in Northern Nigeria and the Bauchi Discussion Circle (BDC).[12][6] The BGIU and BDC were avenues for Zungur to express his radical views, opposed to the Emir's autocracy and the British indirect rule system.[6]

_(16527684520).jpg.webp)

Zungur's radical stance often put him at odds with the colonial authorities, especially the Native Authority. An incident involving him and a European mechanical inspector named John Orgle exemplified this confrontational approach. Orgle had been fond of harassing the female Hausa natives by bringing out his penis in an attempt to court them, leading Zungur to call him a Chilakowa (red-billed hornbill). In response, Orgle pulled out a revolver and shot at Zungur, narrowly missing him. Zungur took legal action against Orgle, and he was subsequently fined five pound sterling by a Jos magistrate court and redeployed elsewhere, serving no prison time.[13][14][15]

He regularly espoused "a secular national state based on "progressive" principles" while utilizing metaphors adapted from his religious heritage.[6] During his time teaching in the 1940s, Zungur was a proponent of Ahmadiyya and Egyptian patterns of Islamic reform but he later abandoned his affiliation with the sect.[7]

Political activities with Azikiwe

In 1946, Nnamdi Azikiwe extended an invitation to Zungur to join his West African Pilot newspaper, which was dedicated to advocating for independence from British colonial rule. Zungur accepted the invitation and assumed the role of the Bauchi Province Correspondent for the newspaper. Around this time, he lead the first public mass demonstration in Northern Nigeria which was a response to the itinerary of Governor John Macpherson's tour, which excluded Bauchi perhaps of the activities of Zungur's BGIU. He was later promoted to the position of North-East Zone correspondent and eventually assumed the role of Chief Correspondent for the Northern Provinces in the West African Pilot in 1947. Later that year, Zungur, alongside Raji Abdullah and Abubakar Zukogi, founded the Fam'iyyar Al'umman Najeriya ta Arewa or the Northern Elements Progressive Association (NEPA) which later became Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU) in 1950.[6]

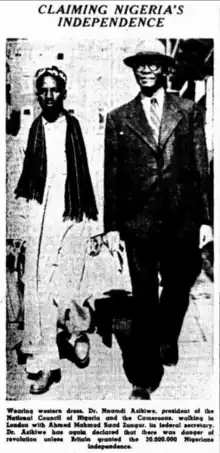

Although Zungur never recovered his health fully, he entered nationalist party politics at an early stage and was a member of the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC).[4] In 1948 he was elected as General Secretary by the NCNC under the presidency of Dr Nnamdi Azikwe. He held this post till 1951 and was as General Secretary that he travelled to London with Azikiwe as the NCNC protest delegation to the Colonial Office to demand for self determination for Nigeria.[3][6] He, however, later abandoned the NCNC due to its "apparent insensitivity to the problems of reform in the North."[7]

Founding of the Northern People's Congress

Zungur was among the founding members of Jam'iyyar Mutanen Arewa or Northern Nigerian Congress, later Northern People's Congress (NPC), and attended in its 26 June 1949 inaugural meeting at Kaduna. At this meeting, he was elected the Adviser on Muslim Law. The primary objective of this organization was to promote the development and advancement of the Northern region. Some of the other founding members included R. A. B. Dikko, Abubakar Imam, Yusuf Maitama Sule and Aminu Kano.[16]: 95–97

They held meetings where they discussed issues regarding the region. One of such meetings included a discussion they held regarding the wording of the proposed constitution. Zungur was particularly interested in this discussion which was said he "dominated". It lasted from 4 p.m. to 4 a.m. the next morning with a two-hour recess. Another was regarding the eligibility of women for membership into the Congress. The members were equally divided on this matter and, as the Adviser on Muslim Law, Zungur was called upon to provide his insights. He drew upon the writings of Usman dan Fodio, the founder of the Sokoto Caliphate and an advocate for women's education, to advocate for the inclusion of women in matters of importance and emphasizing the importance of their participation in various aspects of societal affairs.[16]: 95–97

Formation of NEPU and split from NPC

The Congress discussed matters that concerned the well being of Northerners but was "a good deal" less radical than NEPA which was destroyed by the government due to its radical nature. In August 1950, a faction of more radical members within the Congress decided to establish a new political party, which they named the Northern Elements Progressive Union (NEPU). Founding members of NEPU included notable figures such as Maitama Sule and Abba Maikwaru, with Aminu Kano later joining the party. NEPU's objective was to operate within the broader political landscape, while maintaining an ideological alignment with its precursor, Zungur's Northern Elements Progressive Association.[16]: 96–97

The NPC, partly due to the activities of NEPU, captured the attention of the Northern Nigerian political space, especially some powerful Emirs and administrative officers. As the NPC gained prominence, discussions emerged about the need for a political party that would reflect more conservative values. Some regarded the NPC, with its perceived radical associations, as unsuitable. Within this context, leaders in the North, including prominent politicians like Ahmadu Bello, the then Sardauna of Sokoto, and Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, contemplated forming their own political party with a conservative outlook. The more moderate leaders of NPC feared the party's efforts to become the leading party in the North was futile if they are continued to be associated with radical ideas.[16]: 96–97

Evidence of a split between NEPU and the NPC looked likely, however, this division did not fully materialize until later, in late 1951, following the primary voting phase for the first parliamentary election. The conservative candidates supported by the emirs underperformed against NEPU candidates, leading to a sense of dissatisfaction among the conservative factions. In response to these developments, discussions were initiated between key Northern politicians, notably the Sardauna and Balewa, and leaders within the NPC, including R. A. B. Dikko and Abubakar Imam. On October 1, 1951, it was officially announced that the Northern People's Congress had transitioned into a political party. As part of this announcement, individuals who held civil service positions, including General President Dikko, were advised to resign from their NPC offices. Additionally, Ahmadu Bello and Tafawa Balewa, joined the NPC as members. Zungur remained in the party, retianing his position of Adviser on Muslim Law.[16]: 96–97

A religious or social cleavage must be recognized in politics, but it is unsafe to make it the foundation of a superstructure and to give a separatist turn to the search of security and power. Corporate life cannot be built on the basis of differences. The art of creative politics consists in opening new avenues of cooperation and integrating the differences into a new synthesis

Sa'adu Zungur, unpublished notes in English preparatory to the formulation of the NEPU Political Memorandom of 1956, pp. 8, 11 [17]: 293

Zungur initially aimed to initiate reforms within the party, driven by his belief that the emirate system could be reformed. However, as the years between 1951 and 1954 unfolded, his optimism waned. He encountered significant resistance from both the emirs and the political figures within the NPC who were resistant to his reformist ideas. Recognizing the risks associated with a Northern region that remained resistant to change and isolated from broader progressive trends, Zungur gradually grew disillusioned with the prospects of reform within the existing system. In 1954, amid his increasing disillusionment, Zungur made the decision to disassociate himself from the NPC and aligned himself with the more progressive NEPU, led by Aminu Kano.[6] Before the 1956 elections, he said:

The next three years will surely see the Northern region cut off completely from the rest of Nigeria, under the aegis of a theocratic, one-party fascist government built on the remains of the present feudal autocracies.

Aminu Kano and Zungur referred to their political campaign as a jihad against the emirate authorities. Zungur specifically entitled his memorandums as "Jihadi 131", referring to the 131 seats NEPU was contesting in the election. Their jihad was to be against the "un-islamic feudalism" of the emirate system.[7]: 284–290

Writings

Much like his contemporaries such as Mudi Sipikin, Abubakar Ladan and Aminu Kano, Zungur was a poet who utilized his literary skills to engage in political discourse. His poems, primarily written in the widely understood Hausa language of Northern Nigeria, served as a medium for education and critique. Zungur's poetic compositions were directed towards various aspects of society, the colonial administration, and particularly the authority of the emirate.[18][19][20]

However, due to the sensitive nature of his content, many of his radical political poems were heavily censored in Northern Nigeria. Particularly, works that directly criticized the emirs or the British colonial rule faced severe restrictions. The publication of such works could lead to legal consequences for both the poet and the publisher, resulting in a stifling environment for the dissemination of dissenting views. As a result, many of Zungur's poems were not published.[7] After his death in early 1958, attempts were made by the North Regional Literature Agency (NORLA) to compile all his poems but struggled to locate them. A plea was published on the 19 December issue of Gaskiya Ta Fi Kwabo by the director of NORLA requesting for these poems, promising a reward. After his death in early 1958, the North Regional Literature Agency (NORLA) attempted to compile his poems but had difficulties locating them. In a plea published in the December 19 issue of Gaskiya Ta Fi Kwabo, the director of NORLA requested these poems, offering a reward in return.[21] The compilation was eventually published called Wakokin Sa'adu Zungur. It was later republished by the Northern Nigerian Publishing Company.[22] His poems are still being taught in secondary schools in northern Nigeria.[23]

Arewa Jumhuniya ko Mulkiya

The selection of its [the Native Authority's] gutter elite is being made neither on the basis of intelligence nor capacity, but simply by denial on the decent citizen's outlook. Members of the ruling minority have the readiness of desperadoes to gamble, with nothing to lose but everything to gain.

Sa'adu Zungur, In a letter to the Bauchi Discussion Circle, presented by Aminu Kano in 1943[24]

One of his most renowned works, Arewa Jumhuniya ko Mulkiya ("The North: Republic or Monarchy?"), was composed in 1950 just after his break with the NCNC.[7]: 282 The poem drew inspiration from the events following the independence of India in 1947, which resulted in the dissolution of monarchy in the former British colony. Zungur's poem called upon the Emirs of Northern Nigeria to confront the challenges posed by the emerging era of republicanism. He highlighted the shift towards partisan politics and the emergence of educated elites who sought to take on leadership roles. By referencing the transition in India, Zungur aimed to spark a conversation about the potential need for reform of governance within Northern Nigeria, particularly the emirate system. His poem questioned the relevance of the existing monarchical system in the face of evolving political dynamics. Zungur's work encouraged the Emirs to engage with the changing socio-political landscape and consider the prospects of embracing a more republican approach.[25][26]

Zungur's perspective on the emirate system underwent a significant transformation during the years between 1951 and 1954. His initial hope that the emirs could be reformed to better align with modern political ideals and the changing landscape of Nigeria was quickly soured as his efforts to bring about reform met with resistance from the emirs, which left him disillusioned with the possibility of meaningful change within the existing system. His view on the emirate system shifted from reform to complete destruction.[7]

Death

Sa'adu Zungur passed away on 28 January 1958 due to his lung disorder. Despite being less active in the public eye due to his health, Zungur remained deeply involved in political matters behind the scenes. His illness heavily restricted his activities but his worry of the "destiny of Northern Nigeria" kept him motivated to continue his activism.[2][3] Before his death, he wrote to the District Officer of Bauchi in a Dossier:

I have tried not to write this letter. I have tried to absorb myself in my condition of chronic ill-health. I have tried to put the thoughts of the destiny of Northern Nigeria behind me and tend to my own immediate personal affairs. And I cannot. I go to bed with these thoughts; I get up with them. They are there when I experience ghastly attacks of my neurotic conditions. The same thoughts are there when I say my prayers, or sit to converse with a friend or to read a local daily.[9][27]: 423

References

- ↑ Enwerem, Iheanyi M.; Institut français de recherche en Afrique (1995). A dangerous awakening : the politicization of religion in Nigeria. Internet Archive. Ibadan : IFRA. p. 33. ISBN 978-978-2015-34-1.

- 1 2 3 "Nigeria's Uncelebrated Hero, Poet, Progressive Politician, Intellectual and Nationalist: Ahmad Mahmud Sa'adu Zungur". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Uwechue, Ralph (1991). Makers Of Modern Africa: Profile in History (2nd ed.). United Kingdom: Africa Books Limited. pp. 796–797. ISBN 0903274183.

- 1 2 3 "Sa'adu Zungur: A catalyst for change". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. 2020-02-09. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- ↑ Kirk-Greene, A. (2001). "Sa'adu Zungur: An anthology of the social and political writings of a Nigerian nationalist, by A. M. Yakubu. Kaduna: Nigerian Defence Academy Press, 1999. xiv + 453pp. Naira 1600 paperback. ISBN 978-32929-0-0". African Affairs. 100 (399): 333–335. doi:10.1093/afraf/100.399.333. S2CID 144888022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Adeolu (2017-03-14). "SA'ADU, Mallam Zungur". Biographical Legacy and Research Foundation. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Paden, John N. (1973). Religion and political culture in Kano. Internet Archive. Berkeley, University of California Press. pp. 274–277. ISBN 978-0-520-01738-2.

- ↑ "Bauchi gov't names state university after Sa'adu Zungur - Daily Trust". dailytrust.com. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- 1 2 S, Mohammed I. "Nigeria's Uncelebrated Hero, Poet, Progressive Politician, Intellectual and Nationalist: Ahmad Mahmud Sa'adu Zungur".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Gwarzo, Tahir Haliru (2003). "Activities of Islamic Civic Associations in the Northwest of Nigeria: With Particular Reference to Kano State". Africa Spectrum. 38 (3): 289–318. ISSN 0002-0397. JSTOR 40174992.

- ↑ Feinstein, Alan (1973). African revolutionary; the life and times of Nigeria's Aminu Kano. Internet Archive. [New York] Quadrangle. ISBN 978-0-8129-0321-8.

- ↑ Falola, Toyin; Genova, Ann (2009). Historical Dictionary of Nigeria. United Kingdom: The Scare Crow press, Inc. p. 56. ISBN 9780810863163.

- ↑ admin (2021-02-18). "WHO IS MALLAM SA'ADU ZUNGUR AND WHY HE SHOULD BE IMMORTALIZED". Baushe Daily Times. Retrieved 2023-08-19.

- ↑ Azikiwe, Nnamdi (1970). My odyssey: an autobiography. Internet Archive. London, C. Hurst. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-900966-26-2.

- ↑ Aderinto, Saheed (2018-01-06). Guns and Society in Colonial Nigeria: Firearms, Culture, and Public Order. Indiana University Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-0-253-03162-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sklar, Richard L. (1983). Nigerian political parties : power in an emergent African nation. Internet Archive. New York : NOK Publishers International. ISBN 978-0-88357-100-2.

- ↑ Paden (1973).

- ↑ Introduction to Nigerian literature. Internet Archive. [New York] Africana Pub. Corp. 1972. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8419-0111-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Introduction to African Literature. Internet Archive. 1967. p. 38.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ The living culture of Nigeria. Internet Archive. Lagos ; London : Nelson. 1976. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-17-544201-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ ""Gaskiya ta fi Kwabo, Issue 880, 19 Dec 1958"". Endangered Archives Programme. Retrieved 2023-12-30.

- ↑ Nigeria, Guardian (2017-03-05). "Nigerian written literature since 1914 - Part 1". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. Retrieved 2023-12-30.

- ↑ Furniss, Graham (1984). ""The Way of the World": The Interplay of Meaning and Form in the Interpretation of a Hausa Poem". Research in African Literatures. 15 (1): 25–44. ISSN 0034-5210.

- ↑ Feinstein 1973, p. 90.

- ↑ "Democracy Not Monarchy". www.gamji.com. Retrieved 2023-08-18.

- ↑ Kirk-Greene, A. H. M. (1976). Paden, John N.; Feinstein, Alan; Kano, Aminu; Abdulkadir, Dandatti; Zungur, Sa'adu (eds.). "Zamanin Siyasa: Political Culture and Personalities in Modern Hausaland". African Affairs. 75 (301): 532–535. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 721271.

- ↑ Barber, Karin (2006). Africa's Hidden Histories: Everyday Literacy and Making the Self. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34729-9.