Santa Fe Opera's Crosby Theatre | |

| Address | 301 Opera Drive Santa Fe, New Mexico United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°45′50″N 105°56′49″W / 35.7640°N 105.9470°W |

| Capacity | 2128 plus 106 standees |

| Current use | performing arts center |

| Construction | |

| Opened | July 3, 1957 |

| Rebuilt | 1968, 1998 |

| Architect | 1998 rebuild: James Polshek |

| Website | |

| www | |

Santa Fe Opera (SFO) is an American opera company, located 7 miles (11 km) north of Santa Fe, New Mexico. After creating the Opera Association of New Mexico in 1956, its founding director, John Crosby, oversaw the building of the first opera house on a newly acquired former guest ranch of 199 acres (0.81 km2). The company has presented operas each summer festival season since July 1957, and is internationally known for introducing new operas as well as for its productions of the standard operatic repertoire. Five operas are presented each season during the summer. [1][2]

Since its inception, Santa Fe Opera has staged 45 American premieres and 18 world premieres, including Emmeline, The Tempest, The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, Adriana Mater, and Cold Mountain.[3]

General history

John Crosby, who was a New York-based conductor, founded the company in 1956, initially with the financial support of his parents, who helped in the acquisition of the land and the building of the first opera house. One goal was to give American singers the opportunity to learn and perform new roles while having ample time for rehearsal and preparation in the context of a summer festival situation with the presentation of five operas in repertory. Its first season began on 3 July 1957 with a performance of Puccini's Madama Butterfly with a seating capacity of nearly 500. [4]

Crosby remained as general director until 2000, the longest general directorship in US opera history.[5] Richard Gaddes served as the company's general director from 2000 through 2008.[6][7] In November 2007, SFO named Charles MacKay the company's third general director, effective 1 October 2008.[8] In August 2017, the company announced the intention of MacKay to stand down as its general director after the 2018 season.[9]

In addition to being the opera company's founding general director, Crosby had simultaneously served as its de facto first principal conductor. Alan Gilbert became the company's first music director from 2003 to 2006. Kenneth Montgomery, a regular guest conductor starting in 1982, served as interim music director for the 2007 season.[10][11] In July 2007, Edo de Waart was named as chief conductor, effective 1 October 2007, with an initial contract was of four years. He was the first conductor to hold that title with the company[12][13] However, in November 2008, the company announced that de Waart stood down from the post before the end of his contract, with de Waart citing health and family reasons for this decision.[14] In May 2010, the company announced the appointment of Frédéric Chaslin as the company's next chief conductor, effective 1 October 2010, with an initial contract of three years.[15][16] However, in August 2012, Chaslin resigned as the Opera's chief conductor.[17] In April 2013, the company announced simultaneously the appointments of Harry Bicket as its next chief conductor, effective 1 October 2013, and of Montgomery as conductor laureate for the 2013 season.[18] In November 2016, the company announced the extension of Bicket's contract as chief conductor through 30 September 2020.[19]

In February 2018, the company announced the appointments of Robert K. Meya as its next general director and of Alexander Neef as its first-ever artistic director, and the elevation of Harry Bicket from chief conductor of the company to its music director, with three appointments effective as of 1 October 2018.[20] In October 2018, the company announced the extension of Bicket's contract as music director through the 2023 season.[21] Neef stood down as artistic director in 2021, following his appointment to the Opéra national de Paris.[22] In February 2021, the company announced the appointment of David Lomelí to its newly created post of chief artistic officer, a combination of the past posts of artistic director and director of artistic administration, effective 1 May 2021.[23]

Programming and organizational philosophy

From the beginning, certain characteristics of what was to become a typical season emerged. It runs annually from late June or the beginning of July to the third week of August, with five operas presented in rotating repertory.

Generally, from the time of Crosby's inception of the company, two popular operas opened the season. An American (or world) premiere was generally in the program and these included works commissioned by the company. A lifelong lover of the operas of Richard Strauss, Crosby regularly scheduled one and presented many American premieres of the composer’s work, an example being the 1964 U.S. premiere of the 1938 Daphne. Finally, the fifth opera was often a rarely performed work. The same philosophy continues to the present day. For modern works, US premiere productions of contemporary operas include Thomas Adès' The Tempest (2006), Tan Dun's Tea: A Mirror of Soul, Kaija Saariaho's Adriana Mater,[24] the July 2009 world premiere of The Letter, by composer Paul Moravec and librettist Terry Teachout, and the first full production of Lewis Spratlan's Life Is a Dream in July 2010.[25] World premieres have included Theodore Morrison's Oscar (2013),[26] Jennifer Higdon's Cold Mountain (2015).,[27] and Mason Bates' and Mark Campbell's The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs (2017), [28] and also M. Butterfly (2022) a re-invisioned and socially updated telling of Madama Butterfly. [29] In a recent 2018 world premiere, Doctor Atomic was presented. The opera tells the story of the day before the atomic bomb was tested at the Trinity Site just a couple hundred miles south of Santa Fe and the man who helped to create it, J. Robert Oppenheimer.[30] They are also scheduled this summer to premiere another American opera called "The Righteous" in 2024.[31]

Santa Fe Opera House declared it would open its 2021 season in July. This post-pandemic decision led them to introduce a new position; Covid Compliance and Safety Manager. With a lead from Mike VanAartsen, the Santa Fe Opera began to build protocol surrounding the pandemic, working towards their upcoming season.Their COVID-safe protocols book pulls from VanAartsen's experience with OSHA, federal COVID and Emergency regulations, and suggestions from the AGMA (American Guild of Musical Artists).[32] Pushing to maintain their audience and keep appealing to the younger generations, simulcasts of the dress rehearsals and shows were broadcast outside as a drive-in theater. In the 2021 season, Santa Fe Opera put on four productions and returned to five the following year.[33]

Leadership

General Directors

- John Crosby (1957–2000)

- Richard Gaddes (2000–2008)

- Charles MacKay (2008–2018)

- Robert Meya (2018–present)

Conductors in leadership positions

- John Crosby (1957–2000, de facto principal conductor)

- Alan Gilbert (2003–2006, Music Director)

- Kenneth Montgomery (2007, Acting Music Director)

- Edo de Waart (2007–2009, Chief Conductor)

- Frédéric Chaslin (2010–2012, Chief Conductor)

- Kenneth Montgomery (2013, Conductor Laureate)

- Harry Bicket (2013–2018, Chief Conductor; 2018-present, Music Director)

Apprentice programs

In his first season, Crosby created the Apprentice Singer Program, whereby eight young people were to be given living expenses and paid per performance to be members of the chorus and to cover (understudy) major roles. Unusual for its time in America in the 1950s, the Apprentice Singers Program helped young singers to make the transition from academic to professional life. To date, over 1,500 aspiring opera singers have participated. As Crosby noted:

- "In this country young artists have to do something which is impossible – gain experience. But with our plan, these young people will be scheduled in small roles and will have the opportunity of working with their older brothers and sisters who have already won their spurs. To get such experience now, a young artist has to go to Europe."[34]

The Apprentice Program for Technicians was added in 1965.

The program has formal academic goals in addition to the "hands on" experience provided by the preparation for and participation in professional productions. Seminars and master classes are conducted; singers receive coaching in voice, music, body movement, career counseling, and diction. Technical apprentices are provided with instruction in stage operations, stage properties, costume and wig construction, scenic art, wigs and make up, music services, and stage lighting.

The Apprentice Program for Singers and Technicians continues at The Santa Fe Opera today. Typically, about 1,000 aspiring young singers and 600 technicians apply; in 2014, 43 singers and almost 90 technical apprentices worked at the opera. The Santa Fe Opera offers the only technician apprentice program at an opera house with a budget larger than $15 million in the U.S. [35]

The singers act as the chorus for each opera, as well as performing small roles. In addition, apprentices "cover" some leading roles, and on occasion have been known to have performed, replacing contracted singers who have been indisposed.

The Technical Apprentices perform a variety of backstage functions. They are divided into five separate running crews: costumes, scenery, electrics, properties, and production/music services. These five crews perform the majority of work on the daily changeovers between the five operas of the summer season and also fill positions crucial to the live running of productions. At the end of the summer, the apprentice crews are invited to apply for staff positions for the two weekends of "Apprentice Scenes", a showcase for the apprentice singers, and can serve as everything from costume and lighting designers, to lighting and stage supervisors, to follow spot operators and assistant stage managers and more. There is even an apprentice technicians program for young local high school students who can use what they've learned in school and bring it to a worksite. [36]

Notable past apprentices

Some major American opera singers who have been company apprentices include the sopranos Susanna Phillips (2004), Judith Blegen (1961), Ashley Putnam (1973 and 1975), and Celena Shafer (1999–2000); mezzos Joyce DiDonato (1995), Susan Quittmeyer (1978), and Michelle DeYoung (?); tenors Carl Tanner (1992,93), William Burden (1989–90), Richard Croft (1978), Chris Merritt (1974–75), and Neil Shicoff (1973); baritones David Gockley (1965–67; later general manager of the Houston Grand Opera and the San Francisco Opera) and Sherrill Milnes (1959); and basses Mark Doss (1983), James Morris (1969) and Samuel Ramey (1966).

Many former apprentice singers have returned to perform major roles with the company. These have included Mark Doss in the 2011 Faust; Joyce DiDonato in the 2006 Cendrillon (and again in 2013 in La donna del lago); Chris Merritt also in 2006 in The Tempest; Carl Tanner in the 2005 production of Turandot; and Joyce El-Khoury (2006 and 2008 Apprentice Singer) as Micaëla in the 2014 production of Carmen. Beth Clayton, an apprentice singer during the 1995 season, returned in 2002 in the production of Eugene Onegin. [37]

Theatres and other facilities

There have been three theatres on the present site of The Santa Fe Opera's approximately (now) 150 acres of land. Each has been located on the same site on a mesa, with the audience facing West toward an ever-changing horizon of sunsets and thunderstorms, frequently visible throughout many productions when no backdrops are used. In the first two theaters, the exposure to weather caused occasional cancellations, postponements, or extended intermissions. The rain, the want to improve acoustics, improve patron facilities, comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act, and provide more seating led to the making of the Crosby Theater.

Three features distinguish each of the Santa Fe Opera theaters from any conventional opera house. There is no fly system to allow for scenery to be lowered from above. There is no proscenium arch which does include no curtain and no means for projecting surtitles. And, the sides of the house are open and the rear of the stage may be completely opened to provide westward views.

Performances begin close to sunset, so that the lighting of the productions is not compromised by the sides of the theatre being open to the outside environment. Since the 2011 season, the starting time has been moved up by one half-hour from the original 9pm time. More social aspects of the performance starting time include giving opera-goers the opportunity to observe New Mexico sunsets against the surrounding landscape and the tradition of tailgate dining.[38]

Original theatre, 1957 to 1967

The totally open-air theatre was designed to seat 480 and was built for $115,000 on a site carefully selected by Crosby and an acoustician friend, who fired off a series of rifle shots until they found the perfect natural location for an outdoor theatre. It was "the only outdoor theatre in America exclusively designed for opera".[34] Audience members sat on benches. The Santa Fe firm of McHugh, Hooker, Bradley P. Kidder and Associates were architects for the original theatre; lead architects John W. McHugh and Van Dorn Hooker worked with the acoustical engineer Jack Purcell of Bolt, Beranek and Newman (Boston and Los Angeles).[39] The structural design calculations were performed by Sergio Acosta, a structural engineer and immigrant from Panama who graduated from the University of Texas and was a resident of Albuquerque, NM from 1948 until his death at age 78.

This was the location of the inaugural performance on opening night, 3 July 1957. Madama Butterfly played to a sold-out crowd. By the end of the eight-week season, the 12,000 people who attended accounted for sales at 90% of capacity.

A mezzanine was added in 1965 but, on 27 July 1967, four weeks into the season, a fire destroyed the theatre, causing the company to move to a local downtown high school for the remainder of the season. From the Sweeney Gymnasium, they created the "Sweeney Opera House", and completed the season, albeit without most of the original costumes or sets. A huge fund-raising operation took place, backed by Igor Stravinsky, and $2.4 million was raised to rebuild the theatre in time for the following season.

Rebuilt theatre, 1968 to 1997

The second theatre, a new open-air house seating 1,889, was ready for the start of the new season on 26 June 1968. Just like the company's opening night in 1957, it presented Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

The new theatre was also designed by McHugh and Kidder. One of its principal features was the partial opening of the roof towards the middle of the orchestra section, provided by the curving, audience-facing slope of the stage roof and the thrust of the mezzanine and rear orchestra roof forward. Also, the auditorium's sides were open, as was the rear of the stage (although sliding doors could be closed). It provided for spectacular Westward views – as well as giving some centrally located audience members a view of the night sky.

Most of the new theatre's backstage facilities, including scenery construction and storage and costume and props production, were actually constructed below the stage level in order to preserve the open views to the West. Additionally, a large elevator, located immediately behind the stage and known as the "B-Lift", was included and it became the means whereby scenery could be moved up one level from the scene construction shop to the stage or up or down two levels to or from the large scenery storage area located three levels below the stage. The elevator still remains in place.

Crosby Theatre, since 1998

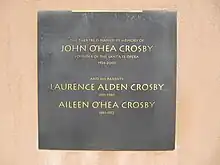

It was renamed the Crosby Theatre not only to honor the founder's death in 2002, but also used to reflect the contributions of his parents,[40] the present theatre was designed by the architectural firm headed by James Polshek of New York.

It was built during extensive reconstruction, which followed the tearing down of the auditorium of the 1968 theatre at the end of the opera season in late August 1997. The stage and backstage facilities such as dressing rooms and the costume shop as well as the scenery construction shop remained in place. The new theatre was completed in ten months for an early July 1998 opening of a new season. Like the previous opening nights of 1957 and 1968, it featured a performance of Madama Butterfly this time sung by Miriam Gauci, the Maltese soprano who had her debut in the same role at the SFO in 1987.

With fewer storm-related problems (and, with a higher stage roof providing a better view of the Westward landscape), the theatre now seats 2,128 plus 106 standees, although it has a strikingly intimate feel. It added a wider and more complete roof structure, with the new front and rear portions supported by cables and joined together with a clerestory window. This offers protection from the sky, but with the sides remaining open to the elements. The presence of wind baffles and, since 2001, Stieren Hall, the orchestra's rehearsal hall, has helped improve exposure on the southern, windward side of the auditorium. A performance of The 13th Child on August 9, 2019, was paused for twenty minutes due to inclement passing weather, a first in the Santa Fe Opera's history. [41]

In 1999, as an alternative to installing a translation system using the projected supertitles (or surtitles), an electronic titles system was installed in the Crosby Theatre. Invented by Figaro Systems of Santa Fe (and only the second one installed after the Metropolitan Opera's Met Titles in 1995), the system provides small rectangular electronic screens in front of each patron's seat, showing a two-line translation of the sung text in either English or Spanish. The system has the possibility of handling up to six languages.

Along with operas, the Crosby Theatre has also played host to numerous concerts in recent years, such as: The B-52s,[42] Wilco,[43] and also St. Vincent and Andrew Bird. [44]

Stieren Orchestra Hall

Completed for the 2001 season under the patronage of Arthur and Jane Stieren, the hall fulfills the long-standing need for an orchestra rehearsal hall. Constructed on three levels with a total of 12,650 square feet (1,175 m2), the building is also used for lectures, recitals, and social events.

On its main level, guide rails attached to the ceiling indicate the dimensions of the theatre's main stage and offstage wings. This allows for scenery to be placed correctly, with access via large sliding doors from the scenery deck level, thus allowing fully staged rehearsals. The upper level contains rehearsal studios for one-on-one coaching for singers while the lower level features a large air-conditioned costume storage facility. The roof of Stieren Orchestra Hall is home to 135 solar panels as the SFO begins to move towards solar power.[45]

Rehearsal halls

Eight rehearsal halls exist on the campus grounds. They vary in size from the reproduction of the full-scale of the Crosby Theatre's stage and down to individual coaching studios for one-on-one coaching. Of the former group, the newest, completed for the 2010 season, is the Richard Gaddes Rehearsal Hall. It complements the existing full-size O'Shaughnessy Hall, which was rehabilitated for the 2012 season. In addition, six other halls of varying sizes allow several productions to be rehearsed simultaneously.

Dapples Pavilion, new cantina

The original "cantina" dating from the 1970s was completely torn down after the 2007 season and construction of a new one was completed in time for the opening of the 2008 season. It contains modern kitchen facilities, new serving stations, and generally good protection from the rain for its patrons. Its arching roof matches the architectural lines of the Crosby Theatre and it bears some resemblance to the roofline of Denver Airport.

Now known as the Dapples Pavilion (named after long-time supporter Florence Dapples), the cantina supplies season-long food and drink for the staff and artists from breakfast time to mid-afternoon. In addition, it functions as the location for pre-performance Preview Buffet dinners for up to about 200 members of the general public in the evenings. The evening includes an introductory talk about the evening's opera.

See also

References

- ↑ Barbour, David. OPERA NEWS; JUL 2016; 81; 1; p16-p16

- ↑ "Summer Opera in Santa Fe | The Hudson Review". hudsonreview.com. Retrieved 2023-03-07.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Dave (April 1, 2022). "Making Welding Magic at the Santa Fe Opera". Welding Journal: 46–49 – via Applied Science and Technology Source.

- ↑ "Golden Years". operanews.com. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ↑ Kozinn, Allan (6 September 2000). "Stepping Aside at an Operatic Oasis; Founding Director of the Santa Fe Opera Looks Back on 43 Years of Innovation". The New York Times.

- ↑ Craig Smith, "SFO to hunt for director's successor". The New Mexican, 9 August 2007.

- ↑ Matthew Westphal (2007-08-09). "Santa Fe Opera General Director Submits (Eventual) Resignation". Playbill Arts. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ↑ Matthew Westphal (2007-11-09). "Santa Fe Opera Appoints New General Director". Playbill Arts. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- ↑ James M Keller (2017-08-11). "Charles MacKay will exit as head of Santa Fe Opera". The Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved 2017-08-14.

- ↑ Matthew Westphal (2007-05-08). "Alan Gilbert Steps Down as Music Director of Santa Fe Opera". Playbill Arts. Retrieved 2007-05-12.

- ↑ Anne Constable, "Santa Fe Opera music director steps down". The Santa Fe New Mexican, 9 May 2007.

- ↑ Matthew Westphal (24 July 2007). "Santa Fe Opera Names Edo de Waart Chief Conductor". Playbill Arts. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- ↑ Craig Smith, "Dutch maestro takes over as chief conductor". The New Mexican, 24 July 2007.

- ↑ Craig Smith (7 November 2008). "De Waart out as Santa Fe Opera's chief conductor". The New Mexican. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ↑ "Frederic Chaslin Appointed Chief Conductor". Santa Fe Opera, 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Anne Constable (4 May 2010). "Composer, pianist to take over as opera conductor". The New Mexican. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ James M Keller (2012-08-28). "Santa Fe Opera's chief conductor resigns". The New Mexican. Archived from the original on 2012-09-01. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- ↑ Anne Constable (24 April 2013). "Harry Bicket named new chief conductor of Santa Fe Opera". The Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ↑ "Santa Fe Opera 2016 Season in Review" (PDF) (Press release). Santa Fe Opera. 17 November 2016. Retrieved 2016-12-27.

- ↑ "SFO Names General Director" (Press release). Santa Fe Opera. 9 February 2018. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- ↑ "The Santa Fe Opera's 2018 Season in Review" (Press release). Santa Fe Opera. 4 October 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-27.

- ↑ "Santa Fe Opera Artistic Director Alexander Neef Will Be the Next Director of Paris National Opera" (Press release). Santa Fe Opera. 27 July 2019. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ↑ "The Santa Fe Opera Appoints David Lomelí as Chief Artistic Officer" (Press release). Santa Fe Opera. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 2021-05-28.

- ↑ Anne Constable, "SFO lineup includes U.S. debut, favorites", The Santa Fe New Mexican, 10 May 2007.

- ↑ Anthony Tommasini (25 July 2010). "Overdue Debut for Composer and Exiled Prince". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- ↑ James M Keller (2013-07-28). "Opera review: Oscar unveiled at Santa Fe Opera". The Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- ↑ Ray Mark Rinaldi (2015-08-04). "Santa Fe Opera ascends with Jennifer Higdon's "Cold Mountain"". Denver Post. Retrieved 2016-12-26.

- ↑ Mark Swed (2017-07-27). "The man, the machine and now Steve Jobs, the opera". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2017-08-14.

- ↑ McLister, Iris (August 2022). "Oh, the Drama!". New Mexico Magazine. p. 64.

- ↑ Aug. 30, Elena Saavedra Buckley News; Now (2018-08-30). "The West's atomic past, in opera halls". www.hcn.org. Retrieved 2023-03-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Santa Fe Opera to premiere 'The Righteous' by Spears, Smith in July 2024". The Independent. 2023-06-07.

- ↑ Eddy, Michael. "Forging a New Role". Stage Directions. 34 (6): 16–17 – via Supplemental Index.

- ↑ "Our View: For Santa Fe Opera, a season of adjustments". The Santa Fe New Mexican. 2023-06-04.

- 1 2 Scott, p. ??

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Dave (April 1, 2022). "Making Welding Magic at the Santa Fe Opera". Welding Journal: 46–49 – via Applied Science and Technology Source.

- ↑ Rosenbaum, Dave (April 1, 2022). "Making Welding Magic at the Santa Fe Opera". Welding Journal: 46–49 – via Applied Science and Technology Source.

- ↑ Adams, Gladi (August 2015). "Patricia Racetter and Beth Clayton: Opera's Gorgeous and Talented Divas". Lesbian Times. 41 (1): 7–12 – via Academic Search Complete.

- ↑ West-Barker, Patricia (July 22, 2008). "Gala delights chefs, diners". The New Mexican. Archived from the original on 2012-02-29.

- ↑ "Santa Fe Opera | SAH ARCHIPEDIA".

- ↑ A dedication plaque on the house exterior names all three Crosbys.

- ↑ Hertelendy, Paul (November 1, 2019). "Paul Ruder's Premiere at Santa Fe Opera: Gut-Wrenching Jenufa". American Record Guide. p. 29.

- ↑ Levin, Jennifer (September 7, 2018). "Roam if they want to: The B-52s play a benefit concert for Kitchen Angels". Santa Fe, New Mexican.

- ↑ Sandford, Brian (September 9, 2022). "Returning to their country roots: Wilco". The Santa Fe New Mexican.

- ↑ Levin, Jennifer (September 14, 2018). "Music for money: Noise for NOW". The Santa Fe New Mexican.

- ↑ Vitu, Teya (2023-04-24). "Santa Fe Opera adding more solar panels". The Santa Fe New Mexican.

Sources

- Huscher, Phillip, The Santa Fe Opera: an American pioneer, Santa Fe, New Mexico: Sunstone Press, June 2006. ISBN 0-86534-550-3

- Scott, Eleanor, The First Twenty Years of The Santa Fe Opera, Santa Fe, New Mexico: Sunstone Press, 1976.

- The Santa Fe Opera − Miracle in the Desert, Santa Fe Opera Shop, 2003.

- Various authors, The Santa Fe Opera – 50th Anniversary supplement to The Santa Fe New Mexican, 28 June 2006. (An illustrated overview of the SFO's 50 years).

External links

Media related to Santa Fe Opera at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Santa Fe Opera at Wikimedia Commons- Official website