Railway tunnels with cutting | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Line | Golden Valley Line |

| Location | Sapperton, Gloucestershire |

| Status | operational |

| Technical | |

| Length | 1 mi 104 yd (1.704 km) |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

The Sapperton Railway Tunnel is a railway tunnel near Sapperton, Gloucestershire in the United Kingdom. It carries the Golden Valley Line from Stroud to Swindon through the Cotswold escarpment. It was begun by the Cheltenham and Great Western Union railway in 1839 and taken over by the Great Western Railway in 1843, being completed in 1845.[1] There are actually two tunnels, the main one at 1 mi 104 yd (1.704 km) in length,[2] and separated by a short gap, a second at 353 yd (323 m).[3]

Construction, engineering, and maintenance difficulties

The initial plans for the tunnel, dating from 1835, were unusual in that it was proposed to construct the tunnel on a curve, but this seems to have been abandoned before any construction was done; some works remain which are thought to relate to the approach route for the original line, but no excavations were made on that line for the tunnel itself. In 1836 "Mr Brunel" was appointed as engineer for the project;[4] this refers to Isambard, but the involvement of "Mark (sic) Brunel" is also recorded.[5] Brunel promised to get rid of the "objectionable" curve, and plans of the revised straight alignment were deposited in 1838. Preliminary shafts were dug, the work beginning in 1837, to ascertain the geological conditions, on the same straight alignment on which the tunnel was eventually built. In 1841 work began on four additional shafts of a larger diameter, quoted as 3 or 6 metres[6] by different sources, plus a trial heading along the tunnel alignment. The line was opened in 1845.

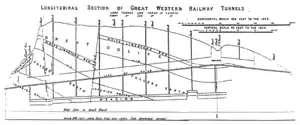

It was found that the intended route passed through a layer of fuller's earth, which was not sufficiently stable to allow construction of a tunnel.[5] The plans were therefore revised to situate the tunnel in more stable strata at a shallower depth, at the expense of steeper gradients on the approaches. This also reduced the length of the tunnel from 2,830 yd (2,590 m), on a 1 in 352 gradient in the 1836 plan, or 2,730 yd (2,500 m) on 1 in 330 in the 1838 plan (1 in 90 in the main tunnel, as built, and 1 in 57 on the approach to it), and so reduced construction costs; a 1950 article, based on the original contract and specification, quoted the directors as saying it would, "considerably diminish its length and expense" and asserted that this was the actual reason for the change to the shallower depth, rather than simply an effect of it. The 1950 article said that the drainage through the oolite was so good that construction was probably started from the foot of each shaft without drainage. Brunel was quoted as reporting in October 1841 that, "the drainage of the water is obtained into the lower oolite, without pumping, at one of the intermediate shafts"[7] Therefore, although it included the geological cross-section (drawn by GWR engineer, Mr. R. P. Brereton),[8] it made no mention of fuller's earth problems.[4] Later articles say the section shows that the header, on the originally-proposed deeper level, passes through a much greater length of fuller's earth than the tunnel as built, and that it also makes it clear that information gained from digging the shafts would have made it apparent that this would be the case.[5]

This diagram also casts doubt on the unsupported assertions which are sometimes made[9][10] that the gap between the two tunnels is the result of a roof collapse in the early days of the tunnel.[11] This gap coincides precisely with the level section at the summit of the line, and also with a dip in the contours of the ground above which brings the ground level below the depth at which the transition from tunnel to cutting is made at the outer ends of the tunnels. It is unlikely that a chance collapse would have taken place to correspond with these features with such convenient precision. The gap is also shown to be in the more stable oolitic strata rather than the unstable stretches of fuller's earth which are more liable to collapse.[12]

The lateral alignment of the revised tunnel route was the same as the planned deeper route, and this left the ten exploratory shafts intersecting the tunnel and continuing as pits up to 6 metres deep below the tunnel floor. The pits were capped with timber to support the track and ballast.[13] However, no records were left as to whether or not the pits had been filled in.

In 1950 a train driver noticed a void beneath the tracks and it became apparent that work was required to stabilise the pits.[14] The original timbers were removed and the pits spanned with prefabricated concrete beams reinforced with bullhead rail and shear links. One more beam was fabricated than was required for the work and this was stored in a nearby yard. Again it was not recorded whether the pits were filled.

In November 2000, heavy flooding caused the collapse of one of the capped shafts. Emergency work over a period of four weeks was carried out to stabilise the collapsed shaft and similar preventative work was carried out on some of the other shafts;[15] the four larger shafts, however, were left untouched. An erroneous report attributes the damage to the collapse of the canal tunnel running underneath;[16] in reality the canal tunnel is to the north of the rail tunnel and does not pass underneath it.

In 2001 it was decided to test the redundant beam remaining from the 1950 operations to destruction in order to determine its strength, as part of surveys intended to discover whether the route would support the loadings required for a route availability index of 8. It was found that the concrete had deteriorated and would not support the loads required for an index of more than 5. Further stabilisation was therefore required as a matter of urgency.

The operation was carried out under a complete possession over a period of seven days by over 100 people working 12-hour shifts, many of whom were accommodated in temporary buildings at the site. Road-rail plant was used, standing on one track of the double-track tunnel to remove the other track and replace the beams underneath. The 1950 beams were cut into three sections using a diamond-tipped saw blade to facilitate removal. Each pit was then spanned with new prefabricated beams, one main support beam under each rail plus additional spacer beams to fill the gap between them. The new beams were fabricated in three sections to avoid exceeding the working load of the plant, which were joined once the beams were in place using stainless steel bolts. After work on the one track was completed, the road-rail plant was put into road mode and driven onto the new beams from where it could work on the other track.

Not until the old beams were removed did it become known that the pits had indeed been backfilled in the course of earlier work and the fears of falling into a six-metre hole were unfounded.

The seven-day possession did not give enough time to fully stabilise all four large shafts. Priority was given to the two least stable ones and the work on those was completed, but the remaining two were only partially stabilised, the beams under the up line being replaced but those under the down line being left alone. A further operation was scheduled for Easter 2002 to perform these final replacements.[5][6][17]

A roof collapse occurred in October 2009, necessitating the closure of the line for relining work.[18][19]

Accidents

A collision took place near Sapperton Tunnel (mis-spelt as "Salperton") on 4 December 1851. A goods train approaching the tunnel from the Swindon direction was overcome by the gradient after passing Tetbury Road station, and the driver decided to divide the train, taking the front portion forward and returning later to collect the rear portion. Unfortunately the brakes on the rear portion failed and it ran back down the gradient to collide with a following train. The goods vehicles were destroyed and the driver and passengers of the following train sustained injuries, but there were no fatalities.[20]

A minor accident occurred at the tunnel on 29 October 1855 also involving a train becoming divided and one portion running away. There were no injuries or deaths and it is thought that no investigation was carried out.[21]

Four platelayers were killed in the tunnel on 14 April 1896. This is mentioned in Hansard for 27 April 1896 (the report mis-spells "Stroud" as "Strood") but no details are given.[22]

On 9 December 2009 a door on an HST came open in the vicinity of the tunnel and a passenger attempted to close it, without success but at some personal risk. A local newspaper attempted to sensationalise the incident by stating that the passenger concerned was "almost thrown from the train" as the door "flew" open. In fact nobody was near the door when it opened, and any risk to the passenger concerned arose entirely as a result of his decision to attempt to close it.[23]

Local councillor Andrew Gravells is quoted as saying that trains should be fitted with devices to prevent departure from stations if doors are open. This requirement already exists,[24] and older slam-door stock such as the HST was retrofitted with a central door locking system in which a power-operated bolt, activated by the guard, prevents the doors from opening while the train is in motion; however this system is not interlocked with the driving controls.[25] It is not clear how the system failed on this occasion; the RAIB was informed of the incident but no report appears to exist on their website.

Disruption to train services was caused on 17 January 2011 when a huntsman and twenty fox-hounds trespassed on the line near the east end of the tunnel. One of the hounds was struck by a train and killed. The train was cancelled and other trains suffered delays. The trespassers had disappeared by the time British Transport Police officers arrived, and no hunt admitted responsibility.[26]

See also

- Sapperton Canal Tunnel runs very close to the railway tunnel.

- List of tunnels in the United Kingdom

References

- ↑ 'Sapperton: Introduction', A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 11. Bisley and Longtree Hundreds. 1976. pp. 87–90. Archived from the original on 16 May 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- ↑ 51°43′25″N 2°6′6″W / 51.72361°N 2.10167°W to 51°42′59.5″N 2°4′48″W / 51.716528°N 2.08000°W

- ↑ 51°42′58.5″N 2°4′44.5″W / 51.716250°N 2.079028°W to 51°42′54″N 2°4′30″W / 51.71500°N 2.07500°W

- 1 2 "The Approaches to Sapperton Railway Tunnels" (PDF). 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Rail Engineer - Featured Articles". December 2009. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Network Rail Media Centre - Victorian Shafts at Sapperton Get Strengthened". 22 October 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ Household, Humphrey (February 1950). "Sapperton Tunnel, Western Region". Railway Magazine. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ↑ "Full text of "Proceedings of the Cotteswold Naturalists' Field Club"". archive.org. May 1870. Archived from the original on 12 July 2013. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ↑ "The Cheltenham Flyer". Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "Diesel multiple unit, 1950s". 10 January 2013. Archived from the original on 26 June 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Cheltenham Flyer - Railway Wonders of the World". railwaywondersoftheworld.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "Early History of the Sapperton Railway Tunnels" (PDF). Gloucestershire Local History Association. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ↑ "Victorian Shafts at Sapperton get strengthened". Network Rail. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ↑ "Accidents". Bygone Transport. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ↑ "Cheltenham-Swindon Rail Line". Hansard. 22 November 2000. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "Chaos over as rail track is reopened". 25 November 2000. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "Sapperton Tunnel, Gloucestershire, UK". Archived from the original on 6 December 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "Swindon to Kemble Railway". 27 October 2009. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "Rail Travel Disruption Monday 26th to Friday 30th October". October 2009. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Great Western Rail Crash". The Cotswold History Blog. 30 May 2011. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ↑ "Accident at Sapperton Tunnel on 29th October 1855". Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "PLATELAYERS KILLED (SAPPERTON TUNNEL)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). HC Deb 27 April 1896 vol 39 cc1732-3. 27 April 1896. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ "Call for inquiry after train door incident". 30 December 2009. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ↑ "Railway Group Standard GM/RT2473 section B7.4" (PDF). February 2003. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "From "USER GUIDE for the operation of CENTRAL DOOR LOCKS on InterCity Slam Door Coaching Stock"". Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "Hunt in Cotswolds strayed on rail line claim". 2 February 2011. Archived from the original on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2013.