Scrambling is a syntactic phenomenon wherein sentences can be formulated using a variety of different word orders without any change in meaning. Scrambling often results in a discontinuity since the scrambled expression can end up at a distance from its head. Scrambling does not occur in English, but it is frequent in languages with freer word order, such as German, Russian, Persian and Turkic languages. The term was coined by Haj Ross in his 1967 dissertation and is widely used in present work, particularly with the generative tradition.

Examples

The following examples from German illustrate typical instances of scrambling:

dass

that

der

the

Mann

man

der

the

Frau

woman

die

the

Bohnen

beans

gab

gave

'that the man gave the woman the beans'

b. dass der Mann die Bohnen der Frau gab c. dass der Frau der Mann die Bohnen gab d. dass der Frau die Bohnen der Mann gab e. dass die Bohnen der Mann der Frau gab f. dass die Bohnen der Frau der Mann gab

These examples illustrate typical cases of scrambling in the midfield of a subordinate clause in German. All six clauses are acceptable, whereby the actual order that appears is determined by pragmatic considerations such as emphasis. If one takes the first clause (clause a) as the basic order, then scrambling has occurred in clauses b–f. The three constituents der Mann, der Frau, and die Bohnen have been scrambled.

Scrambling in German is associated with the midfield, i.e. the part of the sentence that appears between the finite verb and a non-finite verb in main clauses and between the subordinator (= subordinating conjunction) and the finite verb in an embedded clause (= subordinate clause). There is a clear tendency for definite pronouns to appear to the left in the midfield. In this regard, definite pronouns are frequent candidates to undergo scrambling:

weil

because

mich

me

die

the

Kinder

kids

oft

often

ärgern

bother

'because the kids often bother me'

ob

whether

uns

us

jemand

someone

helfen

help

wird

will

'whether someone will help us'

The canonical position of the object in German is to the right of the subject. In this regard, the object pronouns mich in the first example and uns in the second example have been scrambled to the left, so that the clauses now have OS (object-subject) order. The second example is unlike the first example insofar as it, due to the presence of the auxiliary verb wird 'will', necessitates an analysis in terms of a discontinuity.

Standard instances of scrambling in German occur in the midfield, as stated above. There are, however, many non-canonical orderings, whose displaced constituents do not appear in the midfield. One can argue that such examples also involve scrambling:

Erwähnt

mentioned

hat

has

er

he

das

that

nicht.

not

'He didn't mention that.'

The past participle erwähnt has been topicalized in this sentence, but its object, the pronoun das, appears on the other side of the finite verb. There is no midfield involved in this case, which means the non-canonical position in which das appears in relation to its governor erwähnt cannot be addressed in terms of midfield scrambling. The position of das also cannot be addressed in terms of extraposition, since extraposed constituents are relatively heavy, much heavier than das, which is a very light definite pronoun. Given these facts, one can argue that a scrambling discontinuity is present. The definite pronoun das has been scrambled rightward out from under its governor erwähnt. Hence, the example suggests that the scrambling mechanism is quite flexible.

Scrambling is like extraposition (but unlike topicalization and wh-fronting) in a relevant respect; it is clause-bound. That is, one cannot scramble a constituent out of one clause into another:

Sie

she

hat

has

gesagt,

said

dass

that

wir

we

das

that

machen

do

sollten.

should

'She said that we should do that.'

*Sie

she

hat

has

das

that

gesagt,

said,

dass

that

wir

we

machen

do

sollten.

should

The first example has canonical word order; scrambling has not occurred. The second example illustrates what happens when one attempts to scramble the definite pronoun das out of the embedded clause into the main clause. The sentence becomes strongly unacceptable. Extraposition is similar. When one attempts to extrapose a constituent out of one clause into another, the result is unacceptable.

Scrambling within a constituent

Classical Latin and Ancient Greek were known for a more extreme type of scrambling known as hyperbaton, defined as a "violent displacement of words".[1] This involves the scrambling (extraposition) of individual words out of their syntactic constituents. Perhaps the most well-known example is magnā cum laude "with great praise" (lit. "great with praise"). This was possible in Latin and Greek because of case-marking: For example, both magnā and laude are in the ablative case.

Hyperbaton is found in a number of prose writers, e.g. Cicero:

- Hic optimus illīs temporibus est patrōnus habitus[2]

- (word-for-word) he (the) best in those times was lawyer considered

- (meaning) 'He was considered the best lawyer in those times.'

Much more extreme hyperbaton occurred in poetry, often with criss-crossing constituents. An example from Ovid[3] is

- Grandia per multōs tenuantur flūmina rīvōs.

- (word-for-word) great into many are channeled rivers brooks.

- (meaning) 'Great rivers are channeled into many brooks.'

An interlinear gloss is as follows:

grandia

great.NOM.NEUT.PL

per

through

multōs

many.ACC.MASC.PL

tenuantur

are.tapered

flūmina

rivers.NOM.NEUT.PL

rīvōs

brooks.ACC.MASC.PL

'Great rivers are channeled into many brooks.'

The two nouns (subject and object) are placed side-by-side, with both corresponding adjectives extraposed on the opposite side of the verb, in a non-embedding fashion.

Even more extreme cases are noted in the poetry of Horace, e.g.[4]

Quis

Which

multā

many

gracilis

slender

tē

thee

puer

boy

in

in

rōsā

rose

//

//

perfūsus

infused

liquidīs

liquid

urget

urges

odōribus

odors

//

//

grātō,

pleasant,

Pyrrha,

Pyrrha,

sub

under

antrō?

cave?

'What slender Youth bedew'd with liquid odors // Courts thee on (many) Roses in some pleasant cave, // Pyrrha ...?'[5]

Glossed interlinearly, the lines are as follows:

Quis

which.NOM.M.SG

multā

many.ABL.F.SG

gracilis

slender.NOM.M.SG

tē

you.ACC.SG

puer

boy.NOM.M.SG

in

in

rōsā

rose.ABL.F.SG

perfūsus

infused.NOM.M.SG

liquidīs

liquid.ABL.M.PL

urget

urges.3SG

odōribus

odors.ABL.M.PL

grātō

pleasant.ABL.N.SG

Pyrrha

Pyrrha.VOC.F.SG

sub

under

antrō?

cave.ABL.N.SG

Because of the case, gender and number marking on the various nouns, adjectives and determiners, a careful reader can connect the discontinuous and interlocking phrases Quis ... gracilis ... puer, multā ... in rōsā, liquidīs ... odōribus in a way that would be impossible in English.

Theoretical analyses

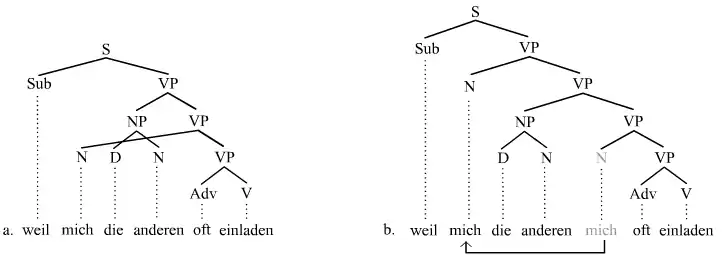

The theoretical analysis of scrambling can vary a lot depending on the theory of sentence structure that one adopts. Constituency-based theories (phrase structure theories) that prefer strictly binary branching structures are likely to address most cases of scrambling in terms of movement (or copying).[6] One or more constituents is assumed to move out of its base position into a derived position. Many other theories of sentence structure, for instance those that allow n-ary branching structures (such as all dependency grammars),[7] see many (but not all!) instances of scrambling involving just shifting; a discontinuity is not involved. The varying analyses are illustrated here using trees. The first tree illustrates the movement analysis of the example above in a theory that assumes strictly binary branching structures. The German subordinate clause weil mich die anderen oft einladen is used, which translates as 'because the others often invite me':

The abbreviation "Sub" stands for "subordinator" (= subordinating conjunction), and "S" stands for "subordinator phrase" (= embedded clause). The tree on the left shows a discontinuity (= crossing lines) and the tree on the right illustrates how a movement analysis deals with the discontinuity. The pronoun mich is generated in a position immediately to the right of the subject; it then moves leftward to reach its surface position. The binary branching structures necessitate this analysis in terms of a discontinuity and movement.

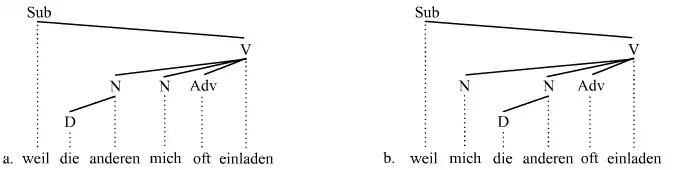

A theory of syntax that rejects the subject-predicate division of traditional grammar (Sentence → NP+VP) and assumes relatively flat structures (that lack a finite VP constituent) will acknowledge no discontinuity in this example. Instead, a shifting analysis addresses many instances of scrambling. The following trees illustrate the shifting-type analysis in a dependency-based grammar.[8] The clause from above is again used (weil mich die anderen oft einladen 'because the others often invite me'):

The tree on the left shows the object in its canonical position to the right of the subject, and the tree on the right shows the object in the derived position to the left of the subject. The important thing to acknowledge about the two trees is that there are no crossing lines. In other words, there is no discontinuity. The absence of a discontinuity is due to the flat structure assumed (which, again, lacks a finite VP constituent). The point, then, is that the relative flatness/layeredness of the structures that one assumes influences significantly the theoretical analysis of scrambling.

The example just examined can be, as just shown, accommodated without acknowledging a discontinuity (if a flat structure is assumed). There are many other cases of scrambling, however, where the analysis must acknowledge a discontinuity, almost regardless of whether relatively flat structures are assumed or not. This fact means that scrambling is generally acknowledged as one of the primary discontinuity types (in addition to topicalization, wh-fronting, and extraposition).

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gildersleeve, B.L. (1895). Gildersleeve's Latin Grammar. 3rd edition, revised and enlarged by Gonzalez Lodge. Houndmills Basingstoke Hampshire: St. Martin's.

- ↑ Brut. line 106, cited in Brett Kesler, Discontinuous constituents in Latin (December 26, 1995).

- ↑ Remedia Amoris, line 445. Quoted in Brett Kesler, Discontinuous constituents in Latin (December 26, 1995), quoting in turn Harm Pinkster (1990), Latin syntax and semantics, London: Routledge, p. 186.

- ↑ Ode 1.5, lines 1–3.

- ↑ Translated by John Milton (1673). The word "many" from the phrase multā in rōsā "in/with many a rose" is left out of Milton's translation.

- ↑ The works of Larson (1988) and Kayne (1994) contributed much to the establishment of strictly binary branching structures in the Chomskyan tradition.

- ↑ Concerning dependency grammars, See Ágel et al. (2003/6).

- ↑ See Groß and Osborne (2009) for a dependency-based analysis of shifting, scrambling, and further mechanisms that alter word order.

References

- Ágel, V., L. Eichinger, H.-W. Eroms, P. Hellwig, H. Heringer, and H. Lobin (eds.) 2003/6. Dependency and valency: An international handbook of contemporary research. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Grewendorf, S. and W. Sternefeld (eds.) 1990. Scrambling and barriers. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

- Groß, T. and T. Osborne 2009. Toward a practical dependency grammar theory of discontinuities. SKY Journal of Linguistics 22, 43–90.

- Karimi, S. 2003. Word order and scrambling. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kayne, R. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph Twenty-Five. MIT Press.

- Larson, R. 1988. On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19, 335–392.

- Müller, G. 1998. Incomplete category fronting. Kluwer: Dordrecht.

- Riemsdijk, H. van and N. Corver (eds.) 1994. Studies on scrambling: Movement and non-movement approaches to free word order. Berlin and New York.

- Ross, J. 1986. Infinite syntax! Norwood, NJ: ABLEX, ISBN 0-89391-042-2.

Further reading

- Perekrestenko, A. "Extending Tree-adjoining grammars and Minimalist Grammars with unbounded scrambling: an overview of the problem area", Actas del VIII congreso de Lingüística General (1994)

- Perekrestenko, A. "Minimalist Grammars with Unbounded Scrambling and Nondiscriminating Barriers Are NP-Hard". Lecture Notes in Computer Science 421–432 (2008). doi:10.1007/978-3-540-88282-4_38