A separable verb is a verb that is composed of a lexical core and a separable particle. In some sentence positions, the core verb and the particle appear in one word, whilst in others the core verb and the particle are separated. The particle cannot be accurately referred to as a prefix because it can be separated from the core verb. German, Dutch, Yiddish,[1] Afrikaans and Hungarian are notable for having many separable verbs. Separable verbs challenge theories of sentence structure because when they are separated, it is not evident how the compositionality of meaning should be understood.

The separation of such verbs is called tmesis.

Examples

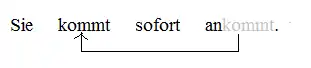

The German verb ankommen is a separable verb, and is used here as the first illustration:

Sie

she

kommt

comes

sofort

immediately

an.

at

'She is arriving immediately.'

Sie

she

kam

came

sofort

immediately

an.

at

'She arrived immediately.'

Sie

she

wird

will

sofort

immediately

ankommen.

at.come

'She will arrive immediately.'

Sie

she

ist

is

sofort

immediately

angekommen.

at.come

'She arrived immediately.'

The first two examples, sentences a and b, contain the "simple" tenses. In matrix declarative clauses that lack auxiliary verbs, the verb and its particle (both in bold) are separated, the verb appearing in V2 position and the particle appearing in clause-final position. The second two examples, sentences c and d, contain the so-called "complex tenses"; they show that when an auxiliary verb appears, the separable verb is not separated, but rather the stem verb and particle appear together as a single word.

The following two examples are from Dutch:

Ik

I

kom

come

morgen

tomorrow

aan.

at

'I am arriving tomorrow.'

Hij

he

is

is

aangekomen.

at.come

'He has arrived.'

The Dutch verb aankomen is separable, as illustrated in the first sentence with the simple present tense, whereas when an auxiliary verb appears (here is) as in the second sentence with present perfect tense/aspect, the lexical verb and its particle appear together as a single word.

The following examples are from Hungarian:

Leteszem

up.I.hang

a

the

telefont.

phone

'I hang up the phone.'

Nem

not

teszem

I.hang

le

up

a

the

telefont.

phone

'I do not hang up the phone.'

The verb letesz is separated in the negative sentence. Affixes in Hungarian are also separated from the verb in imperative and prohibitive moods. Moreover, word order influences the strength of prohibition, as the following examples show:

Ne

not

tedd

hang

le

up

a

the

telefont.

phone

'Don't hang up the phone.'

Le

up

ne

not

tedd

hang

a

the

telefont.

phone

'Don't you hang up the phone!' (stronger prohibition)

Analogy to English

English has many phrasal or compound verb forms that are somewhat analogous to separable verbs. However, in English the preposition or verbal particle is either an invariable prefix (e.g. understand) or is always a separate word (e.g. give up), without the possibility of grammatically conditioned alternations between the two. An adverbial particle can be separated from the verb by intervening words (e.g. up in the phrasal verb screw up appears after the direct object, things, in the sentence He is always screwing things up). Although the verbs themselves never alternate between prefix and separate word, the alternation is occasionally seen across derived words (e.g. something that is outstanding stands out).

Structural analysis

Separable verbs challenge the understanding of meaning compositionality because when they are separated, the two parts do not form a constituent. Hence theories of syntax that assume that form–meaning correspondences should be understood in terms of syntactic constituents are faced with a difficulty, because it is not apparent what sort of syntactic unit the verb and its particle build. One prominent means of addressing this difficulty is via movement. Given that languages like German and Dutch are actually subject–object–verb (SOV) languages (as opposed to SVO), when separation occurs, the lexical verb must have moved out of the clause-final position to a derived position further to the left, e.g. in German

The verb kommt is seen as originating in a position where it appeared with its particle an, but it then moves leftward to the V2 position.

Different meaning

When a prefix can be used both separably and inseparably, there are cases where the same verb can have different meanings depending on whether its prefix is separable or inseparable (an equivalent example in English would be take over and overtake).

German

In German, among other languages, some verbs can exist as separable and inseparable forms with different meanings. For the verb umfahren one even gets opposite meanings:

The infinitive forms of these two verbs umfahren are only identical in written form. When spoken, the non-separable form is stressed as umfahren, whereas the separable is stressed as umfahren.

Dutch

The same happens in Dutch, which is related to German and English. Sometimes the meanings are quite different, even if they have correspondences in the cognate English verbs:

Examples: