Serabit el-Khadim (Arabic: سرابيط الخادم Arabic pronunciation: [saraːˈbiːtˤ alˈxaːdɪm]; also transliterated Serabit al-Khadim, Serabit el-Khadem) is a locality in the southwest Sinai Peninsula, Egypt, where turquoise was mined extensively in antiquity, mainly by the ancient Egyptians. Archaeological excavation, initially by Sir Flinders Petrie, revealed ancient mining camps and a long-lived Temple of Hathor, the Egyptian goddess who was favoured as a protector in desert regions and known locally as the mistress of the turquoise. The temple was first established during the Middle Kingdom in the reign of Sesostris I (reigned 1971 BC to 1926 BC) and was partly reconstructed in the New Kingdom.[1]

Archaeological findings

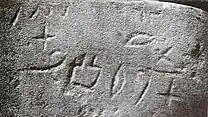

Thirty incised graffiti in a "Proto-Sinaitic script" shed light on the history of the alphabet.[2] The mines were worked by prisoners of war from southwest Asia who presumably spoke a Northwest Semitic language, such as the Canaanite that was ancestral to Phoenician and Hebrew. The incisions date from the beginning of the 16th century BC.[3]

Romanus François Butin of Catholic University of America published articles in the Harvard Theological Review based on the 1927 Harvard Mission to Serabit and the 1930 Harvard-Catholic University Joint Expedition. His article "The Serabit Inscriptions: II. The Decipherment and Significance of the Inscriptions" provides an early detailed study of the inscriptions and some dozen black and white photographs, hand-drawings and analysis of the previously published inscriptions, #346, 349, 350–354, and three new inscriptions, #355–368. At that time, #355 was still in situ at Serabit but had not been photographed by the previous Harvard Mission. In 1932, he wrote:

The present article was begun with the limited purpose of making known the new inscriptions discovered by the Harvard-Catholic University Joint Expedition to Serabit in the spring of 1930. In the course of this study, I perceived that some signs doubtful in the inscriptions already published were made clear by the new slabs, and I decided to go over the entire field again.[4]

Gallery

1840s sketch from The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia

1840s sketch from The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia.jpg.webp) Sarabit el Khadim in the 1869 Ordnance Survey of the Peninsula of Sinai

Sarabit el Khadim in the 1869 Ordnance Survey of the Peninsula of Sinai.jpg.webp) 1906 map of Flinders Petrie

1906 map of Flinders Petrie 2009

2009

See also

References

- ↑ Fuller, Michael J. "Serabit Temple". St Louis Community College. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- ↑ McCarter, P. Kyle. "The Early Diffusion of the Alphabet". The Biblical Archaeologist. 37 (3 (September 1974:54–68)): 56–58.

- ↑ "Sinaitic inscriptions | ancient writing". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ↑ Vol. 25:2 (1932) The Serabit Expedition of 1930: IV. The Protosinaitic Inscriptions

Sources

- Albright, W. F. (April 1948). "The Early Alphabetic Inscriptions from Sinai and Their Decipherment". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. Oakland (110): 6–22. doi:10.2307/3218767. JSTOR 3218767. S2CID 163924917.

- Butin, Romain F. (January 1928). "The Serâbît Inscriptions: II. The Decipherment and Significance of the Inscriptions". Harvard Theological Review. Cambridge University Press. 21 (1): 9–67. doi:10.1017/S0017816000021167. S2CID 163011970.

- Butin, Romain F. (April 1932). "The Protosinaitic Inscriptions". Harvard Theological Review. 25 (2): 130–203. doi:10.1017/S0017816000001231. S2CID 161237361.

- Flinders Petrie, W. M. (1906). Researches in Sinai. London: John Murray.

- Giveon, R. (1978). The Stones of Sinai speak. Tokyo: Galuseisha. ASIN B0007B5V1A.

- Eckenstein, Lina (1921). A History of Sinai. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Lake, Kirsopp; Blake, Robert P. (January 1928). "The Serâbît Inscriptions: I. The Rediscovery of the Inscriptions". Harvard Theological Review. 21 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1017/S0017816000021155. S2CID 161474162.