| Serotonin syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Serotonin toxicity, serotonin toxidrome, serotonin sickness, serotonin storm, serotonin poisoning, hyperserotonemia, serotonergic syndrome, serotonin shock |

| |

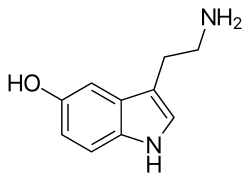

| Serotonin | |

| Specialty | Critical care medicine, psychiatry |

| Symptoms | High body temperature, agitation, increased reflexes, tremor, sweating, dilated pupils, diarrhea[1][2] |

| Usual onset | Within a day[2] |

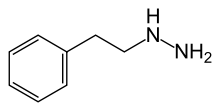

| Causes | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), amphetamine, methylene blue, pethidine (meperidine), tramadol, dextromethorphan, ondansetron, cocaine[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and medication use[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome, malignant hyperthermia, anticholinergic toxicity, heat stroke, meningitis[2] |

| Treatment | Active cooling[1] |

| Medication | Benzodiazepines, cyproheptadine[1] |

| Frequency | Unknown[3] |

Serotonin syndrome (SS) is a group of symptoms that may occur with the use of certain serotonergic medications or drugs.[1] The symptoms can range from mild to severe, and are potentially fatal.[4][5][2] Symptoms in mild cases include high blood pressure and a fast heart rate; usually without a fever.[2] Symptoms in moderate cases include high body temperature, agitation, increased reflexes, tremor, sweating, dilated pupils, and diarrhea.[1][2] In severe cases, body temperature can increase to greater than 41.1 °C (106.0 °F).[2] Complications may include seizures and extensive muscle breakdown.[2]

Serotonin syndrome is typically caused by the use of two or more serotonergic medications or drugs.[2] This may include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), amphetamines, pethidine (meperidine), tramadol, dextromethorphan, buspirone, L-tryptophan, 5-hydroxytryptophan, St. John's wort, triptans, ecstasy (MDMA), metoclopramide, or cocaine.[2] It occurs in about 15% of SSRI overdoses.[3] It is a predictable consequence of excess serotonin on the central nervous system.[6] Onset of symptoms is typically within a day of the extra serotonin.[2]

Diagnosis is based on a person's symptoms and history of medication use.[2] Other conditions that can produce similar symptoms such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome, malignant hyperthermia, anticholinergic toxicity, heat stroke, and meningitis should be ruled out.[2] No laboratory tests can confirm the diagnosis.[2]

Initial treatment consists of discontinuing medications which may be contributing.[1] In those who are agitated, benzodiazepines may be used.[1] If this is not sufficient, a serotonin antagonist such as cyproheptadine may be used.[1] In those with a high body temperature, active cooling measures may be needed.[1] The number of cases of SS that occur each year is unclear.[3] With appropriate medical intervention the risk of death is low, likely less than 1%.[7] The high-profile case of Libby Zion, who is generally accepted to have died from SS, resulted in changes to graduate medical school education in New York State.[6][8]

Signs and symptoms

Symptom onset is usually relatively rapid, SS encompasses a wide range of clinical findings. Mild symptoms may consist of increased heart rate, shivering, sweating, dilated pupils, myoclonus (intermittent jerking or twitching), as well as overresponsive reflexes.[6] (Many of these symptoms may be side effects of the drug or drug interaction causing excessive levels of serotonin rather than an effect of elevated serotonin itself.) Tremor is a common side effect of MDMA's action on dopamine, whereas hyperreflexia is symptomatic of exposure to serotonin agonists. Moderate intoxication includes additional abnormalities such as hyperactive bowel sounds, high blood pressure and hyperthermia; a temperature as high as 40 °C (104 °F). The overactive reflexes and clonus in moderate cases may be greater in the lower limbs than in the upper limbs. Mental changes include hypervigilance or insomnia and agitation.[6] Severe symptoms include severe increases in heart rate and blood pressure. Temperature may rise to above 41.1 °C (106.0 °F) in life-threatening cases. Other abnormalities include metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, seizures, kidney failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation; these effects usually arising as a consequence of hyperthermia.[6][9]

The symptoms are often present as a clinical triad of abnormalities:[6][10]

- Cognitive effects: headache, agitation, hypomania, mental confusion, hallucinations, coma

- Autonomic effects: shivering, sweating, hyperthermia, vasoconstriction, tachycardia, nausea, diarrhea.

- Somatic effects: myoclonus (muscle twitching), hyperreflexia (manifested by clonus), tremor.

Causes

Numerous medications and street drugs can cause SS when taken alone at high doses or in combination with other serotonergic agents. The table below lists some of these.

Many cases of serotonin toxicity occur in people who have ingested drug combinations that synergistically increase synaptic serotonin.[10] It may also occur due to an overdose of a single serotonergic agent.[27] The combination of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) with precursors such as L-tryptophan or 5-hydroxytryptophan pose a particularly acute risk of life-threatening serotonin syndrome.[28] The case of combination of MAOIs with tryptamine agonists (commonly known as ayahuasca) can present similar dangers as their combination with precursors, but this phenomenon has been described in general terms as the cheese effect. Many MAOIs irreversibly inhibit monoamine oxidase. It can take at least four weeks for this enzyme to be replaced by the body in the instance of irreversible inhibitors.[29] With respect to tricyclic antidepressants, only clomipramine and imipramine have a risk of causing SS.[30]

Many medications may have been incorrectly thought to cause SS. For example, some case reports have implicated atypical antipsychotics in SS, but it appears based on their pharmacology that they are unlikely to cause the syndrome.[31] It has also been suggested that mirtazapine has no significant serotonergic effects and is therefore not a dual action drug.[32] Bupropion has also been suggested to cause SS,[33][34] although as there is no evidence that it has any significant serotonergic activity, it is thought unlikely to produce the syndrome.[35] In 2006 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an alert suggesting that the combined use of SSRIs or SNRIs and triptan medications or sibutramine could potentially lead to severe cases of SS.[36] This has been disputed by other researchers, as none of the cases reported by the FDA met the Hunter criteria for SS.[36][37] The condition has however occurred in surprising clinical situations, and because of phenotypic variations among individuals, it has been associated with unexpected drugs, including mirtazapine.[38][39]

The relative risk and severity of serotonergic side effects and serotonin toxicity, with individual drugs and combinations, is complex. SS has been reported in patients of all ages, including the elderly, children, and even newborn infants due to in utero exposure.[40][41][42][43] The serotonergic toxicity of SSRIs increases with dose, but even in overdose, it is insufficient to cause fatalities from SS in healthy adults.[44][45] Elevations of central nervous system (CNS) serotonin will typically only reach potentially fatal levels when drugs with different mechanisms of action are mixed together.[9] Various drugs, other than SSRIs, also have clinically significant potency as serotonin reuptake inhibitors, (such as tramadol, amphetamine, and MDMA) and are associated with severe cases of the syndrome.[6][46]

Although the most significant health risk associated with opioid overdoses is respiratory depression,[47] it is still possible for an individual to develop SS from certain opioids without the loss of consciousness. However, most cases of opioid-related SS involve the concurrent use of a serotergenic drug such as antidepressants.[48] Nonetheless, it is not uncommon for individuals taking opioids to also be taking antidepressants due to the comorbidity of pain and depression.[49]

Cases where opioids alone are the cause of SS are typically seen with tramadol, because of its dual mechanism as a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.[50][51] SS caused by tramadol can be particularly problematic if an individual taking the drug is unaware of the risks associated with it and attempts to self-medicate symptoms such as headache, agitation, and tremors with more opioids, further exacerbating the condition.

Pathophysiology

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter involved in multiple complex biological processes including aggression, pain, sleep, appetite, anxiety, depression, migraine, and vomiting.[10] In humans the effects of excess serotonin were first noted in 1960 in patients receiving an MAOI and tryptophan.[52] The syndrome is caused by increased serotonin in the CNS.[6] It was originally suspected that agonism of 5-HT1A receptors in central grey nuclei and the medulla was responsible for the development of the syndrome.[53] Further study has determined that overstimulation of primarily the 5-HT2A receptors appears to contribute substantially to the condition.[53] The 5-HT1A receptor may still contribute through a pharmacodynamic interaction in which increased synaptic concentrations of a serotonin agonist saturate all receptor subtypes.[6] Additionally, noradrenergic CNS hyperactivity may play a role as CNS norepinephrine concentrations are increased in SS and levels appear to correlate with the clinical outcome. Other neurotransmitters may also play a role; NMDA receptor antagonists and γ-aminobutyric acid have been suggested as affecting the development of the syndrome.[6] Serotonin toxicity is more pronounced following supra-therapeutic doses and overdoses, and they merge in a continuum with the toxic effects of overdose.[44][54]

Spectrum concept

A postulated "spectrum concept" of serotonin toxicity emphasises the role that progressively increasing serotonin levels play in mediating the clinical picture as side effects merge into toxicity. The dose-effect relationship is the effects of progressive elevation of serotonin, either by raising the dose of one drug, or combining it with another serotonergic drug which may produce large elevations in serotonin levels.[55] Some experts prefer the terms serotonin toxicity or serotonin toxidrome, to more accurately reflect that it is a form of poisoning.[9][56]

Diagnosis

There is no specific test for SS. Diagnosis is by symptom observation and investigation of the person's history.[6] Several criteria have been proposed. The first evaluated criteria were introduced in 1991 by Harvey Sternbach.[6][29][57] Researchers later developed the Hunter Toxicity Criteria Decision Rules, which have better sensitivity and specificity, 84% and 97%, respectively, when compared with the gold standard of diagnosis by a medical toxicologist.[6][10] As of 2007, Sternbach's criteria were still the most commonly used.[9]

The most important symptoms for diagnosing SS are tremor, extreme aggressiveness, akathisia, or clonus (spontaneous, inducible and ocular).[10] Physical examination of the patient should include assessment of deep tendon reflexes and muscle rigidity, the dryness of the mucosa of the mouth, the size and reactivity of the pupils, the intensity of bowel sounds, skin color, and the presence or absence of sweating.[6] The patient's history also plays an important role in diagnosis, investigations should include inquiries about the use of prescription and over-the-counter drugs, illicit substances, and dietary supplements, as all these agents have been implicated in the development of SS.[6] To fulfill the Hunter Criteria, a patient must have taken a serotonergic agent and meet one of the following conditions:[10]

- Spontaneous clonus, or

- Inducible clonus plus agitation or diaphoresis, or

- Ocular clonus plus agitation or diaphoresis, or

- Tremor plus hyperreflexia, or

- Hypertonism plus temperature > 38 °C (100 °F) plus ocular clonus or inducible clonus

Differential diagnosis

Serotonin toxicity has a characteristic picture which is generally hard to confuse with other medical conditions, but in some situations it may go unrecognized because it may be mistaken for a viral illness, anxiety disorders, neurological disorder, anticholinergic poisoning, sympathomimetic toxicity, or worsening psychiatric condition.[6][9][58] The condition most often confused with serotonin syndrome is neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS).[59][60] The clinical features of neuroleptic malignant syndrome and SS share some features which can make differentiating them difficult.[61] In both conditions, autonomic dysfunction and altered mental status develop.[53] However, they are actually very different conditions with different underlying dysfunction (serotonin excess vs dopamine blockade). Both the time course and the clinical features of NMS differ significantly from those of serotonin toxicity.[10] Serotonin toxicity has a rapid onset after the administration of a serotonergic drug and responds to serotonin blockade such as drugs like chlorpromazine and cyproheptadine. Dopamine receptor blockade (NMS) has a slow onset, typically evolves over several days after administration of a neuroleptic drug, and responds to dopamine agonists such as bromocriptine.[6][53]

Differential diagnosis may become difficult in patients recently exposed to both serotonergic and neuroleptic drugs. Bradykinesia and extrapyramidal "lead pipe" rigidity are classically present in NMS, whereas SS causes hyperkinesia and clonus; these distinct symptoms can aid in differentiation.[23][62]

Management

Management is based primarily on stopping the usage of the precipitating drugs, the administration of serotonin antagonists such as cyproheptadine (with a regimen of 12 mg for the initial dose followed by 2 mg every 2 hours until clinical),[63] and supportive care including the control of agitation, the control of autonomic instability, and the control of hyperthermia.[6][64][65] Additionally, those who ingest large doses of serotonergic agents may benefit from gastrointestinal decontamination with activated charcoal if it can be administered within an hour of overdose.[9] The intensity of therapy depends on the severity of symptoms. If the symptoms are mild, treatment may only consist of discontinuation of the offending medication or medications, offering supportive measures, giving benzodiazepines for myoclonus, and waiting for the symptoms to resolve. Moderate cases should have all thermal and cardiorespiratory abnormalities corrected and can benefit from serotonin antagonists. The serotonin antagonist cyproheptadine is the recommended initial therapy, although there have been no controlled trials demonstrating its efficacy for SS.[9][66][67] Despite the absence of controlled trials, there are a number of case reports detailing apparent improvement after people have been administered cyproheptadine.[9] Animal experiments also suggest a benefit from serotonin antagonists.[68] Cyproheptadine is only available as tablets and therefore can only be administered orally or via a nasogastric tube; it is unlikely to be effective in people administered activated charcoal and has limited use in severe cases.[9] Cyproheptadine can be stopped when the person is no longer experiencing symptoms and the half life of serotonergic medications already passed.[2]

Additional pharmacological treatment for severe case includes administering atypical antipsychotic drugs with serotonin antagonist activity such as olanzapine.[6] Critically ill people should receive the above therapies as well as sedation or neuromuscular paralysis.[6] People who have autonomic instability such as low blood pressure require treatment with direct-acting sympathomimetics such as epinephrine, norepinephrine, or phenylephrine.[6] Conversely, hypertension or tachycardia can be treated with short-acting antihypertensive drugs such as nitroprusside or esmolol; longer acting drugs such as propranolol should be avoided as they may lead to hypotension and shock.[6] The cause of serotonin toxicity or accumulation is an important factor in determining the course of treatment. Serotonin is catabolized by monoamine oxidase A in the presence of oxygen, so if care is taken to prevent an unsafe spike in body temperature or metabolic acidosis, oxygenation will assist in dispatching the excess serotonin. The same principle applies to alcohol intoxication. In cases of SS caused by MAOIs, oxygenation will not help to dispatch serotonin. In such instances, hydration is the main concern until the enzyme is regenerated.

Agitation

Specific treatment for some symptoms may be required. One of the most important treatments is the control of agitation due to the extreme possibility of injury to the person themselves or caregivers, benzodiazepines should be administered at first sign of this.[6] Physical restraints are not recommended for agitation or delirium as they may contribute to mortality by enforcing isometric muscle contractions that are associated with severe lactic acidosis and hyperthermia. If physical restraints are necessary for severe agitation they must be rapidly replaced with pharmacological sedation.[6] The agitation can cause a large amount of muscle breakdown. This breakdown can cause severe damage to the kidneys through a condition called rhabdomyolysis.[69]

Hyperthermia

Treatment for hyperthermia includes reducing muscle overactivity via sedation with a benzodiazepine. More severe cases may require muscular paralysis with vecuronium, intubation, and artificial ventilation.[6][9] Suxamethonium is not recommended for muscular paralysis as it may increase the risk of cardiac dysrhythmia from hyperkalemia associated with rhabdomyolysis.[6] Antipyretic agents are not recommended as the increase in body temperature is due to muscular activity, not a hypothalamic temperature set point abnormality.[6]

Prognosis

Upon the discontinuation of serotonergic drugs, most cases of SS resolve within 24 hours,[6][9][70][71] although in some cases delirium may persist for a number of days.[29] Symptoms typically persist for a longer time frame in patients taking drugs which have a long elimination half-life, active metabolites, or a protracted duration of action.[6]

Cases have reported persisting chronic symptoms,[72] and antidepressant discontinuation may contribute to ongoing features.[73] Following appropriate medical management, SS is generally associated with a favorable prognosis.[74]

Epidemiology

Epidemiological studies of SS are difficult as many physicians are unaware of the diagnosis or they may miss the syndrome due to its variable manifestations.[6][75] In 1998 a survey conducted in England found that 85% of the general practitioners that had prescribed the antidepressant nefazodone were unaware of SS.[41] The incidence may be increasing as a larger number of pro-serotonergic drugs (drugs which increase serotonin levels) are now being used in clinical practice.[66] One postmarketing surveillance study identified an incidence of 0.4 cases per 1000 patient-months for patients who were taking nefazodone.[41] Additionally, around 14–16% of persons who overdose on SSRIs are thought to develop SS.[44]

Notable cases

The most widely recognized example of SS was the death of Libby Zion in 1984.[76] Zion was a freshman at Bennington College at her death on March 5, 1984, at age 18. She died within 8 hours of her emergency admission to the New York Hospital Cornell Medical Center. She had an ongoing history of depression, and came to the Manhattan hospital on the evening of March 4, 1984, with a fever, agitation and "strange jerking motions" of her body. She also seemed disoriented at times. The emergency room physicians were unable to diagnose her condition definitively but admitted her for hydration and observation. Her death was caused by a combination of pethidine and phenelzine.[77] A medical intern prescribed the pethidine.[78] The case influenced graduate medical education and residency work hours. Limits were set on working hours for medical postgraduates, commonly referred to as interns or residents, in hospital training programs, and they also now require closer senior physician supervision.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ferri, Fred F. (2016). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1154–1155. ISBN 9780323448383.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Volpi-Abadie J, Kaye AM, Kaye AD (2013). "Serotonin syndrome". The Ochsner Journal. 13 (4): 533–40. PMC 3865832. PMID 24358002.

- 1 2 3 Domino, Frank J.; Baldor, Robert A. (2013). The 5-Minute Clinical Consult 2014. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1124. ISBN 9781451188509.

- ↑ New, Andrea M.; Nelson, Sarah; Leung, Jonathan G. (2015-10-01). Alexander, Earnest; Susla, Gregory M. (eds.). "Psychiatric Emergencies in the Intensive Care Unit". AACN Advanced Critical Care. 26 (4): 285–293. doi:10.4037/NCI.0000000000000104. ISSN 1559-7768. PMID 26484986.

- ↑ Boyer EW , Shannon M . The serotonin syndrome . N Engl J Med. 2005 ; 352 ( 11 ): 1112-1120

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 Boyer EW, Shannon M (March 2005). "The serotonin syndrome" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867. PMID 15784664. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-18.

- ↑ Friedman, Joseph H. (2015). Medication-Induced Movement Disorders. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 9781107066007.

- 1 2 Brensilver JM, Smith L, Lyttle CS (September 1998). "Impact of the Libby Zion case on graduate medical education in internal medicine". The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York. 65 (4): 296–300. PMID 9757752.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Isbister GK, Buckley NA, Whyte IM (September 2007). "Serotonin toxicity: a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment". Med J Aust. 187 (6): 361–5. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01282.x. PMID 17874986. S2CID 13108173. Archived from the original on 2009-04-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM (September 2003). "The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity". QJM. 96 (9): 635–642. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg109. PMID 12925718.

- 1 2 3 Ener RA, Meglathery SB, Van Decker WA, Gallagher RM (March 2003). "Serotonin syndrome and other serotonergic disorders". Pain Medicine. 4 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03005.x. PMID 12873279.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Prescribing Practice Review 32: Managing depression in primary care" (PDF). National Prescribing Service Limited. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2006.

- ↑ Isenberg D, Wong SC, Curtis JA (September 2008). "Serotonin syndrome triggered by a single dose of suboxone". American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 26 (7): 840.e3–5. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2008.01.039. PMID 18774063.

- 1 2 Gnanadesigan N, Espinoza RT, Smith RL (June 2005). "The serotonin syndrome". New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (23): 2454–2456. doi:10.1056/NEJM200506093522320. PMID 15948273.

- ↑ Schep LJ, Slaughter RJ, Beasley DM (August 2010). "The clinical toxicology of metamfetamine". Clinical Toxicology. 48 (7): 675–694. doi:10.3109/15563650.2010.516752. PMID 20849327. S2CID 42588722.

- ↑ "Vyvanse (Lisdexamfetamine Dimesylate) Drug Information: Side Effects and Drug Interactions – Prescribing Information". RxList.com. Archived from the original on 2017-03-25. Retrieved 2017-03-22.

- ↑ "Adderall (Amphetamine, Dextroamphetamine Mixed Salts) Drug Information: Side Effects and Drug Interactions – Prescribing Information". RxList. Archived from the original on 2017-03-23. Retrieved 2017-03-22.

- ↑ "AMT". DrugWise.org.uk. 2016-01-03. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ↑ Alpha-methyltryptamine (AMT) – Critical Review Report (PDF) (Report). World Health Organisation – Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (published 2014-06-20). 20 June 2014. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- ↑ Bijl D (October 2004). "The serotonin syndrome". Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 62 (9): 309–313. PMID 15635814.

Mechanisms of serotonergic drugs implicated in serotonin syndrome ... Stimulation of serotonin receptors ... LSD

- ↑ Braun U, Kalbhen DA (October 1973). "Evidence for the Biogenic Formation of Amphetamine Derivatives from Components of Nutmeg". Pharmacology. 9 (5): 312–316. doi:10.1159/000136402. PMID 4737998.

- ↑ "Erowid Yohimbe Vaults: Notes on Yohimbine by William White, 1994". Erowid.org. Archived from the original on 2013-01-26. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- 1 2 Birmes P, Coppin D, Schmitt L, Lauque D (May 2003). "Serotonin syndrome: a brief review". CMAJ. 168 (11): 1439–42. PMC 155963. PMID 12771076.

- ↑ Steinberg M, Morin AK (January 2007). "Mild serotonin syndrome associated with concurrent linezolid and fluoxetine". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 64 (1): 59–62. doi:10.2146/ajhp060227. PMID 17189581.

- ↑ Karki SD, Masood GR (2003). "Combination risperidone and SSRI-induced serotonin syndrome". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 37 (3): 388–391. doi:10.1345/aph.1C228. PMID 12639169. S2CID 36677580.

- ↑ Verre M, Bossio F, Mammone A, et al. (2008). "Serotonin syndrome caused by olanzapine and clomipramine". Minerva Anestesiologica. 74 (1–2): 41–45. PMID 18004234. Archived from the original on 2009-01-08.

- ↑ Foong AL, Grindrod KA, Patel T, Kellar J (October 2018). "Demystifying serotonin syndrome (or serotonin toxicity)". Canadian Family Physician. 64 (10): 720–727. PMC 6184959. PMID 30315014.

- ↑ Sun-Edelstein C, Tepper SJ, Shapiro RE (September 2008). "Drug-induced serotonin syndrome: a review". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 7 (5): 587–596. doi:10.1517/14740338.7.5.587. PMID 18759711. S2CID 71657093.

- 1 2 3 Sternbach H (June 1991). "The serotonin syndrome". American Journal of Psychiatry. 148 (6): 705–713. doi:10.1176/ajp.148.6.705. PMID 2035713. S2CID 29916415.

- ↑ Gillman, P. Ken (2006-06-01). "A Review of Serotonin Toxicity Data: Implications for the Mechanisms of Antidepressant Drug Action". Biological Psychiatry. 59 (11): 1046–1051. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.016. ISSN 0006-3223. PMID 16460699. S2CID 12179122.

- ↑ Isbister GK, Downes F, Whyte IM (April 2003). "Olanzapine and serotonin toxicity". Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 57 (2): 241–42. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1819.2003.01110.x. PMID 12667176. S2CID 851495.

- ↑ Gillman P (2006). "A systematic review of the serotonergic effects of mirtazapine in humans: implications for its dual action status". Human Psychopharmacology. 21 (2): 117–125. doi:10.1002/hup.750. PMID 16342227. S2CID 23442056.

- ↑ Munhoz RP (2004). "Serotonin syndrome induced by a combination of bupropion and SSRIs". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 27 (5): 219–222. doi:10.1097/01.wnf.0000142754.46045.8c. PMID 15602102.

- ↑ Thorpe EL, Pizon AF, Lynch MJ, Boyer J (June 2010). "Bupropion induced serotonin syndrome: a case report". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 6 (2): 168–171. doi:10.1007/s13181-010-0021-x. PMC 3550303. PMID 20238197.

- ↑ Gillman PK (June 2010). "Bupropion, bayesian logic and serotonin toxicity". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 6 (2): 276–77. doi:10.1007/s13181-010-0084-8. PMC 3550296. PMID 20440594.

- 1 2 Evans RW (2007). "The FDA alert on serotonin syndrome with combined use of SSRIs or SNRIs and Triptans: an analysis of the 29 case reports". MedGenMed. 9 (3): 48. PMC 2100123. PMID 18092054.

- ↑ Wenzel RG, Tepper S, Korab WE, Freitag F (November 2008). "Serotonin syndrome risks when combining SSRI/SNRI drugs and triptans: is the FDA's alert warranted?". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 42 (11): 1692–1696. doi:10.1345/aph.1L260. PMID 18957623. S2CID 24942783.

- ↑ Duggal HS, Fetchko J (April 2002). "Serotonin syndrome and atypical antipsychotics". American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (4): 672–73. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.672-a. PMID 11925312.

- ↑ Boyer and Shannon's reply to Gillman PK (June 2005). "The serotonin syndrome". New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (23): 2454–2456. doi:10.1056/NEJM200506093522320. PMID 15948272.

- ↑ Laine K, Heikkinen T, Ekblad U, Kero P (July 2003). "Effects of exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors during pregnancy on serotonergic symptoms in newborns and cord blood monoamine and prolactin concentrations". Archives of General Psychiatry. 60 (7): 720–726. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.720. PMID 12860776.

- 1 2 3 Mackay FJ, Dunn NR, Mann RD (November 1999). "Antidepressants and the serotonin syndrome in general practice". Br J Gen Pract. 49 (448): 871–4. PMC 1313555. PMID 10818650.

- ↑ Isbister GK, Dawson A, Whyte IM, Prior FH, Clancy C, Smith AJ (September 2001). "Neonatal paroxetine withdrawal syndrome or actually serotonin syndrome?". Archives of Disease in Childhood. Fetal and Neonatal Edition. 85 (2): F147–48. doi:10.1136/fn.85.2.F145g. PMC 1721292. PMID 11561552.

- ↑ Gill M, LoVecchio F, Selden B (April 1999). "Serotonin syndrome in a child after a single dose of fluvoxamine". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 33 (4): 457–459. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70313-6. PMID 10092727.

- 1 2 3 Isbister G, Bowe S, Dawson A, Whyte I (2004). "Relative toxicity of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in overdose". J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 42 (3): 277–85. doi:10.1081/CLT-120037428. PMID 15362595. S2CID 43121327.

- ↑ Whyte IM, Dawson AH (2002). "Redefining the serotonin syndrome [abstract]". Journal of Toxicology: Clinical Toxicology. 40 (5): 668–69. doi:10.1081/CLT-120016866. S2CID 218865517.

- ↑ Vuori E, Henry J, Ojanperä I, Nieminen R, Savolainen T, Wahlsten P, Jäntti M (2003). "Death following ingestion of MDMA (ecstasy) and moclobemide". Addiction. 98 (3): 365–368. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00292.x. PMID 12603236.

- ↑ Boyer EW (July 2012). "Management of opioid analgesic overdose". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (2): 146–155. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1202561. PMC 3739053. PMID 22784117.

- ↑ Rickli, Anna; et al. (2018). "Opioid-induced Inhibition of the Human 5-HT and Noradrenaline Transporters in Vitro: Link to Clinical Reports of Serotonin Syndrome". British Journal of Pharmacology. 175 (3): 532–543. doi:10.1111/bph.14105. PMC 5773950. PMID 29210063.

- ↑ Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K (November 2003). "Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review". Archives of Internal Medicine. 163 (20): 2433–2445. doi:10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. PMC 3739053. PMID 14609780.

- ↑ "Tramadol Hydrochloride". drugs.com. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ↑ Takeshita J, Litzinger MH (2009). "Serotonin Syndrome Associated With Tramadol". Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 11 (5): 273. doi:10.4088/PCC.08l00690. PMC 2781045. PMID 19956471.

- ↑ Oates JA, Sjoerdsma A (December 1960). "Neurologic effects of tryptophan in patients receiving a monoamine oxidase inhibitor". Neurology. 10 (12): 1076–8. doi:10.1212/WNL.10.12.1076. PMID 13730138. S2CID 40439836.

- 1 2 3 4 Whyte, Ian M. (2004). "Serotonin Toxicity/Syndrome". Medical Toxicology. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins. pp. 103–6. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ↑ Whyte I, Dawson A, Buckley N (2003). "Relative toxicity of venlafaxine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in overdose compared to tricyclic antidepressants". QJM. 96 (5): 369–74. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg062. PMID 12702786.

- ↑ Gillman PK (June 2004). "The spectrum concept of serotonin toxicity". Pain Med. 5 (2): 231–2. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2004.04033.x. PMID 15209988.

- ↑ Gillman PK (June 2006). "A review of serotonin toxicity data: implications for the mechanisms of antidepressant drug action". Biol Psychiatry. 59 (11): 1046–51. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.016. PMID 16460699. S2CID 12179122.

- ↑ Hegerl U, Bottlender R, Gallinat J, Kuss HJ, Ackenheil M, Möller HJ (1998). "The serotonin syndrome scale: first results on validity". Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 248 (2): 96–103. doi:10.1007/s004060050024. PMID 9684919. S2CID 37993326. Archived from the original on 1999-10-11.

- ↑ Fennell J, Hussain M (2005). "Serotonin syndrome: case report and current concepts". Ir Med J. 98 (5): 143–4. PMID 16010782.

- ↑ Nisijima K, Shioda K, Iwamura T (2007). "Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin syndrome". Neurobiology of Hyperthermia. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 162. pp. 81–104. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(06)62006-2. ISBN 9780444519269. PMID 17645916.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ↑ Tormoehlen, LM; Rusyniak, DE (2018). "Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin syndrome". Thermoregulation: From Basic Neuroscience to Clinical Neurology, Part II. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 157. pp. 663–675. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64074-1.00039-2. ISBN 9780444640741. PMID 30459031.

- ↑ Christensen V, Glenthøj B (2001). "[Malignant neuroleptic syndrome or serotonergic syndrome]". Ugeskrift for Lægerer. 163 (3): 301–2. PMID 11219110.

- ↑ Isbister GK, Dawson A, Whyte IM (September 2001). "Citalopram overdose, serotonin toxicity, or neuroleptic malignant syndrome?". Can J Psychiatry. 46 (7): 657–9. doi:10.1177/070674370104600718. PMID 11582830.

- ↑ Scotton, William J; Hill, Lisa J; Williams, Adrian C; Barnes, Nicholas M (2019). "Serotonin Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Clinical Features, Management, and Potential Future Directions". International Journal of Tryptophan Research. SAGE Publications. 12: 117864691987392. doi:10.1177/1178646919873925. ISSN 1178-6469. PMC 6734608. PMID 31523132.

- ↑ Sporer K (1995). "The serotonin syndrome. Implicated drugs, pathophysiology and management". Drug Saf. 13 (2): 94–104. doi:10.2165/00002018-199513020-00004. PMID 7576268. S2CID 19809259.

- ↑ Frank, Christopher (2008). "Recognition and treatment of serotonin syndrome". Can Fam Physician. 54 (7): 988–92. PMC 2464814. PMID 18625822.

- 1 2 Graudins A, Stearman A, Chan B (1998). "Treatment of the serotonin syndrome with cyproheptadine". J Emerg Med. 16 (4): 615–9. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(98)00057-2. PMID 9696181.

- ↑ Gillman PK (1999). "The serotonin syndrome and its treatment". J Psychopharmacol (Oxford). 13 (1): 100–9. doi:10.1177/026988119901300111. PMID 10221364. S2CID 17640246.

- ↑ Nisijima K, Yoshino T, Yui K, Katoh S (January 2001). "Potent serotonin (5-HT)(2A) receptor antagonists completely prevent the development of hyperthermia in an animal model of the 5-HT syndrome". Brain Res. 890 (1): 23–31. doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(00)03020-1. PMID 11164765. S2CID 29995925.

- ↑ "Serotonin syndrome – PubMed Health". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-02-01. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ↑ Prator B (2006). "Serotonin syndrome". J Neurosci Nurs. 38 (2): 102–5. doi:10.1097/01376517-200604000-00005. PMID 16681290.

- ↑ Jaunay E, Gaillac V, Guelfi J (2001). "[Serotonin syndrome. Which treatment and when?]". Presse Med. 30 (34): 1695–700. PMID 11760601.

- ↑ Chechani V (February 2002). "Serotonin syndrome presenting as hypotonic coma and apnea: potentially fatal complications of selective serotonin receptor inhibitor therapy". Crit Care Med. 30 (2): 473–6. doi:10.1097/00003246-200202000-00033. PMID 11889332. S2CID 28908329.

- ↑ Haddad PM (2001). "Antidepressant discontinuation syndromes". Drug Saf. 24 (3): 183–97. doi:10.2165/00002018-200124030-00003. PMID 11347722. S2CID 26897797.

- ↑ Mason PJ, Morris VA, Balcezak TJ (July 2000). "Serotonin syndrome. Presentation of 2 cases and review of the literature". Medicine (Baltimore). 79 (4): 201–9. doi:10.1097/00005792-200007000-00001. PMID 10941349. S2CID 41036864.

- ↑ Sampson E, Warner JP (November 1999). "Serotonin syndrome: potentially fatal but difficult to recognize". Br J Gen Pract. 49 (448): 867–8. PMC 1313553. PMID 10818648.

- ↑ Brody, Jane (February 27, 2007). "A Mix of Medicines That Can Be Lethal". New York Times. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- ↑ Asch DA, Parker RM (March 1988). "The Libby Zion case. One step forward or two steps backward?". N Engl J Med. 318 (12): 771–5. doi:10.1056/NEJM198803243181209. PMID 3347226.

- ↑ Jan Hoffman (January 1, 1995). "Doctors' Accounts Vary In Death of Libby Zion". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 16, 2009. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

External links

- Image demonstrating findings in moderately severe serotonin syndrome from Boyer EW, Shannon M (2005). "The serotonin syndrome". N Engl J Med. 352 (11): 1112–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867. PMID 15784664. S2CID 37959124.