| Siege of the Salamanca forts | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Peninsular War | |||||||

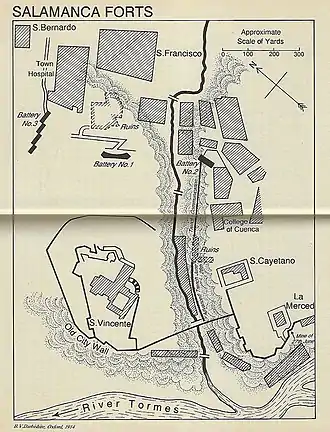

1858 map of Salamanca shows empty spaces in the southwest corner of the city where the forts were located | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

40,800 36 guns |

48,000 4 guns 6 howitzers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

800 killed, wounded or captured 36 guns lost |

99 killed 331 wounded | ||||||

The siege of the Salamanca forts (17–27 June 1812) saw an 800-man Imperial French garrison directed by Lieutenant Colonel Duchemin defend three fortified convents in the city of Salamanca against the 48,000-strong Allied army led by Arthur Wellesley, Lord Wellington. During this time, the French commander Marshal Auguste de Marmont led a 40,000-man French army in an unsuccessful attempt to relieve the garrison. An Allied failure to bring sufficient artillery ammunition caused the siege to be prolonged. The garrison repulsed a premature British attempt to storm the fortified convents on 23 June, but finally surrendered four days later after an artillery bombardment breached one fort and set another one on fire. During his maneuvering, Marmont formed the idea that Wellington was only willing to act on the defensive. This mistaken notion would contribute to Marmont's defeat at the Battle of Salamanca a month later.

Background

Strategic situation

On 20 January 1812, the Anglo-Portuguese army commanded by Wellington successfully concluded the siege of Ciudad Rodrigo.[1] This was followed by the siege of Badajoz, which ended on 6 April 1812 when Wellington's army stormed and captured that city.[2] With these two victories, the strategic initiative in the Iberian Peninsula passed from the French to the Allies under Wellington. At the same time, the Emperor Napoleon lost interest in Spain as he turned his energies to his planned French invasion of Russia. He ordered 27,000 Imperial Guards and Polish units withdrawn from Spain, weakening the French occupation forces. Napoleon ordered that his brother King Joseph Bonaparte and Joseph's chief of staff Marshal Jean-Baptiste Jourdan assume the overall command of the French armies in Spain. In reality, Marshal Louis-Gabriel Suchet in eastern Spain, Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult in Andalusia, and Marshal Marmont in western Spain would continue to act as independent commanders. Also, the French army in northern Spain was never placed under Joseph's orders. In May 1812, there were 230,000 French troops in Spain, but half of these were occupying forces in northeast Spain and unavailable for field operations against Wellington.[3]

Wellington decided to take 48,000 troops and move against Marmont's Army of Portugal. Meanwhile, Lieutenant General Rowland Hill with 18,000 Anglo-Portuguese soldiers would watch Badajoz. To keep Marmont from being reinforced, Wellington arranged for Spanish forces under Major General Francisco Ballesteros to harass Soult's forces in the south and for British Admiral Home Riggs Popham to conduct raids on the northern coast of Spain. Marmont's army counted 52,000 soldiers, but only 35,000 were immediately available for field operations and these were dispersed in order to obtain food. One of his divisions was stationed in Asturias and could not be used without Napoleon's permission. Joseph and Jourdan had 18,000 men around Madrid but 6,000 of these were unreliable pro-French Spanish troops. Joseph ordered Marmont and Soult to cooperate in the event of an Allied offensive, but Soult absolutely refused.[4]

Operations

On 13 June, Wellington's army crossed the Rio Águeda near Ciudad Rodrigo in three columns on a front 10 miles (16 km) wide. The advance continued steadily over the next three days. The right wing consisted of the 1st, 6th, and 7th Infantry Divisions. The center was made up of the Light, 4th, and 5th Infantry Divisions. The left wing included the 3rd Infantry Division and two independent Portuguese brigades led by Brigadier Generals Denis Pack and Thomas Bradford. All three columns were covered by cavalry units.[5] With the exception of the 1st and Light Divisions, Wellington organized all his infantry divisions with one Portuguese and two British or King's German Legion brigades. The 1st Division had one King's German Legion brigade and two British brigades while the Light Division had two brigades, each formed from British and Portuguese light infantry.[6] On 16 June, as it neared Salamanca, the center column's cavalry chased away some French light cavalry.[7]

When Marmont received news on 14 June of the Allied offensive, he immediately ordered his army to concentrate at Fuentesaúco, 20 miles (32 km) north of Salamanca.[8] His army included two cavalry divisions and the infantry divisions of Generals of Division Maximilien Sébastien Foy, Bertrand Clausel, Claude François Ferey, Jacques Thomas Sarrut, Antoine Louis Popon de Maucune, Antoine François Brenier de Montmorand, and Jean Guillaume Barthélemy Thomières, in numerical order from 1st to 7th.[9] Brenier and Maucune and General of Brigade Jean-Baptiste Théodore Curto's light cavalry evacuated Salamanca and fell back to the rendezvous point. Foy marched from Ávila far to the southeast, Clausel came from Peñaranda de Bracamonte to the southeast, Ferey started from Valladolid to the northeast, Thomières marched from Zamora to the northwest, Sarrut came from Toro to the north, and General of Brigade Pierre François Xavier Boyer's dragoons started from Toro and from Benavente far to the north. By 19 June, Marmont had 36,000 infantry, 2,800 cavalry, and 80 artillery pieces assembled at Fuentesaúco. Despite Napoleon's instructions, Marmont also called in General of Division Jean Pierre François Bonet's 6,500 men from the Asturias, but these soldiers could not arrive for nearly three weeks.[8]

Wellington's army counted 28,000 British and 17,000 Portuguese, and a division of 3,000 Spaniards led by Major General Carlos de España, altogether 48,000 men. With 3,500 cavalry, the Allies were superior to the French for the first time in this arm. Both Marmont and Wellington had an accurate idea of their opponent's strength and both were eager to fight a battle.[10] However, Marmont preferred to wait until Bonet's division arrived so that his numbers would nearly equal his adversary's strength. The French commander also hoped to be reinforced by 8,000 troops from General of Division Marie-François Auguste de Caffarelli du Falga's Army of the North. These troops would assemble at Vitoria and march southwest. At this time Soult insisted that Wellington was about to descend upon Andalusia with 60,000 troops, when only Hill's 18,000 were observing his forces. Because of Soult's pleas for help, Joseph and Jourdan at Madrid were initially unsure whether Marmont or Soult was the British commander's real target.[11]

Siege

Initial bombardment

On 17 June, Wellington's army enveloped Salamanca, with the left wing going north of the city and the center and right wing circling to the south. The three columns joined on the north side of Salamanca and then advanced 3 miles (4.8 km) to the San Christobal heights. Wellington hoped that besieging the Salamanca forts would goad Marmont into attacking him on the heights. Only the 14th Light Dragoons and the British 6th Division entered the city to lay siege to the forts. The Spanish citizens were delighted that the French were gone and gave the Allies a joyous welcome in the Plaza Mayor. Wellington set up his headquarters in the city while Major General Henry Clinton's 6th Division invested the forts. In order to prepare the forts for defense, Marmont's sappers had demolished a large part of the old University quarter in the southwest part of the city.[12]

Wellington had been led to believe that the forts were hastily prepared medieval convents and that their reduction would be relatively easy. Because of this belief, the Allied army brought only four 18-pounder long guns, each with only 100 shot. In fact, the three convents were massively reinforced using masonry from the dismantled University buildings, oak beams, and earth. The convents had their walls doubled in thickness, their windows blocked up, their surroundings guarded by scarps, counter-scarps, and palisades. Mounting 30 cannons, the largest fort, San Vincente was located at the southwest angle of the old city wall. San Cayetano with four cannons was southeast of San Vincente. South of San Cayetano was La Merced with two guns that prevented the Allies using the Roman bridge over the Rio Tormes. San Vincente and La Merced overlooked the Tormes and were virtually impregnable against an attack from the south and west. Only the north sides of San Vincente and San Cayetano appeared promising to attack. San Vincente was separated from San Cayetano and La Merced by a ravine that ran southwest into the Tormes. The three forts were designed to be mutually supporting; any column attacking one fort could expect to come under a crossfire from the other forts.[13]

The French garrison consisted of six flank companies from the 17th Light, and the 15th, 65th, 82nd, and 86th Line Infantry Regiments plus an artillery company. Duchemin of the 65th Line commanded 800 soldiers and 36 mostly light guns.[13] The British 6th Division included the 1st Brigade under Major General Richard Hulse, the 2nd Brigade led by Major General Barnard Foord Bowes, and the Portuguese brigade under Brigadier General Conde de Rezende. The 1st Brigade was made up of the 1/11th Foot, 2/53rd Foot, 1/61st Foot battalions, and one company of the 5/60th Foot. The 2nd Brigade comprised the 2nd Foot, 1/32nd Foot, 1/36th Foot battalions. The Portuguese brigade included the 9th Caçadores Battalion, and two battalions each of the 8th and 12th Line Regiments.[6] Lieutenant Colonel John Fox Burgoyne was the ranking engineer officer and Lieutenant Colonel May of the Royal Artillery commanded the 18-pounders.[13]

Burgoyne chose a position for the 18-pounders 250 yards (229 m) north of San Vincente.[13] On the night of 17 June, 400 soldiers from the 6th Division began to dig the battery position. The working parties had no experience in siege work and the French had the area under cannon fire and musketry all night. In the morning the trench was only knee-deep and the workers had to be pulled back under cover. That night an exploring party was discovered and several men wounded by the defenders. The besiegers added 300 sharpshooters from the King's German Legion to their force in order to suppress the fire of the defenders. [14] May borrowed three howitzers and two 6-pound cannons from the field artillery[13] and put both cannons in the San Bernardo convent. These guns were too small to smash the walls, but their fire would annoy the defenders.[14]

By the morning of 19 June, the first battery was completed and the four 18-pounders and three howitzers opened fire, causing some damage to San Vincente. Meanwhile, two more battery locations were started, one to the west near San Bernardo and one to the east near the College of Cuenca. Two of the howitzers were moved into the Cuenca battery, but they came under such deadly fire that 20 gunners became casualties that day. On 20 June, Colonel Alexander Dickson arrived with[14] a train of six 24-pound howitzers from the Portuguese fortress of Elvas.[13] The three borrowed howitzers were sent back to the field artillery. Two of the 18-pounders were moved to the Cuenca battery and their fire brought down part of San Vincente's roof, killing some of its defenders. Seeing that his artillery was running low on ammunition, Wellington sent a request to Almeida for an ammunition resupply convoy. The bombardment was suspended.[14]

Relief attempt

Having assembled his army, Marmont advanced toward Salamanca on 20 June, pushing back the Allies' cavalry patrols. Wellington posted his army with his right flank at Cabrerizos on the Tormes and his left flank at San Cristóbal de la Cuesta. From right to left, were the 1st, 7th, 4th, Light, and 3rd Divisions and then Pack's and Bradford's brigades. The 5th Division, Hulse's brigade of the 6th Division, and España's division were held in reserve. Major General Victor Alten's light cavalry brigade guarded the right flank while Colonel William Ponsonby's light cavalry brigade covered the left. The heavy cavalry brigades of Major Generals John Le Marchant and Eberhardt Otto George von Bock were in reserve. The two remaining brigades of the 6th Division maintained the investment of the three forts. Marmont's troops occupied Castellanos de Moriscos and then attacked Moriscos. The 68th Foot repulsed three attacks but Wellington pulled the unit back into his main defense line that night.[15]

Wellington expected to be attacked on the morning of 21 June, but Marmont initiated no action because the divisions of Foy and Thomières and one dragoon brigade did not arrive until the afternoon. That morning, Wellington might have crushed his outnumbered adversary and his staff wondered why their chief did not attack. According to a letter he sent to Prime Minister Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, Wellington hoped to stage another defensive victory like the Battle of Bussaco. That evening Marmont held a Council of war in which Maucune and Ferey advised him to attack but Clausel and Foy persuaded him not to. On 22 June, British commander realized Marmont was not going to attack. Still hoping to provoke an attack, Wellington had the 51st Foot and the 68th Foot from the British 7th Division drive the French from a knoll near Moriscos. This was accomplished with a British loss of seven killed and 26 wounded. That night, Marmont's army withdrew 6 miles (10 km) to a position near Aldearrubia with its left flank at Huerta near the Tormes. On 23 June, Wellington sent Hulse's brigade back to Salamanca and ordered Clinton to renew the siege of the forts.[16] He also sent Bock's cavalry to patrol the west bank of the Tormes opposite Huerta.[17]

Assault

On 23 June, Clinton renewed the siege of the three forts despite the handicap of having very little ammunition. The four 18-pounders only had 60 rounds altogether and the six howitzers had only 160 shells between them. The engineers and gunners decided to ignore San Vincente because it was too strong. Instead, they focused on reducing San Cayetano. With this in mind, one of the 18-pounders was moved to the San Bernardo battery in order to get an enfilade on a vulnerable point in San Cayetano. After firing all morning, the 18-pounders ran out of ammunition in the afternoon. San Cayetano was considerably damaged, but there was no breach in its walls. Despite this, Wellington ordered an assault to be carried out at 10 pm that night.[17]

The attacking force was made up of the six light companies from the brigades of Hulse and Bowes, approximately 300–400 men. Since there was no breach, the men carried 20 ladders in order to reach the parapet. The officers observed that, "the undertaking was difficult, and the men seemed to feel it". The assault was launched from some ruins near the Cuenca battery. As soon as the storming column burst from cover it came under deadly cannon and musket fire not only from San Cayetano, but from San Vincente as well. There were casualties from the first moment. Only two ladders were put up but no one dared to climb them, since by then it was clear that the attack was hopeless. The other ladders were poorly made and some fell apart as they were being carried. Bowes was slightly wounded at once while leading the assault. He dressed his wound and rushed back into the battle only to be killed at the foot of the ladders. The assault failed with a loss of six officers and 120 men killed or wounded.[17] The British requested a truce to gather their dead and wounded, but the French refused and Bowes' corpse was not recovered until later.[18]

Final bombardment

The early morning of 24 June saw a heavy fog, accompanied by the muted sounds of musketry and by the occasional thud of a cannon firing. When the fog dissipated at 7 am, Wellington and his staff could see Bock's cavalry retreating before two French infantry divisions and a light cavalry brigade that had crossed the Tormes. The British army commander ordered Lieutenant General Thomas Graham to take the 1st and 7th Divisions and Le Marchant's cavalry across the river at Santa Marta de Tormes and block the French thrust. The French pressed ahead to the village of Calvarrasa de Abajo beyond which they found Graham's divisions deployed in a strong position. Suddenly, the French turned around and fell back across the Huerta fords. The Allies did not pursue. Graham's troops soon returned to their previous positions on the east bank. Neither army budged on 25 June. On this day, soldiers of the 6th Division completed a trench along the bottom of the ravine, cutting off San Vincente from the other two forts.[19]

On the morning of 26 June, the ammunition convoy finally arrived. The artillerists moved all four 18-pounders into the San Bernardo battery and directed their fire at San Cayetano. Four howitzers were placed in the Cuenca battery and ordered to fire red hot shot into the roof of San Vincente. The bombardment began at 3 pm and continued all night long. Altogether, 18 separate fires started in the roof and tower of San Vincente and were put out by the garrison. A large amount of wood had been used by the French in order to strengthen the fort, and this provided the fuel. After four more hours of pounding on the morning of 27 June, the 18-pounders smashed a breach in the walls of San Cayetano. A new fire broke out in San Vincente; it ignited the main store of planks and threatened to explode the gunpowder magazine. Up until this time, the French return fire was intense, but the exhausted garrison's fire began to taper off. Wellington ordered San Cayetano to be stormed.[20]

The storming column formed in the ravine below San Cayetano. Just as the men were about to charge, a white flag appeared at the breach. The French commander asked for a truce, requesting a chance to communicate with Duchemin, and promising to surrender in two hours. Wellington demanded a surrender in five minutes, but the French officer continued to bargain. Despite this, the storming column came out of the ravine and rushed the fort. A few scattered shots wounded six attackers, then San Cayetano's garrison threw down their weapons. By this time, the fire in San Vincente was raging and a white flag waved there also. Duchemin asked for a three-hour truce, but Wellington repeated his earlier promise to storm the place in five minutes if no surrender was forthcoming. Duchemin tried to stall, but the 9th Caçadores emerged from the ravine and entered the fort. There was no resistance and the French flag was quickly hauled down. The source did not mention how or when La Merced surrendered.[20]

Result

British casualties were five officers and 94 men killed and 29 officers and 302 men wounded. French losses during the siege numbered 3 officers and 40 men killed, 11 officers and 140 men wounded, and slightly less than 600 unwounded men captured. Of the 14 killed or wounded officers, five belonged to the 65th Line, two each to the 15th Line and 17th Light, one each to the 86th, artillery, and engineers, and two were unaccounted for. In addition, the Allies captured 36 guns of various calibers, a good supply of gunpowder, and a substantial amount of clothing. The Allies razed the three forts. The seized gunpowder was handed over to d'España's soldiers. On 7 July, careless handling caused a portion of the gunpowder to detonate, killing 20 civilians and some soldiers, and wrecking several houses.[21]

On 26 June, Marmont received a letter from the Army of the North in which Caffarelli explained that his reinforcements were not coming after all. Popham's naval squadron appeared in the Bay of Biscay and the Spanish guerillas began wreaking havoc in the north. Caffarelli could not spare a man because of these incursions. When, at dawn on 27 June, Duchemin signaled that he was still holding out, Marmont resolved on a desperate attempt to maneuver south of Salamanca. A few hours later, the forts ceased fire and soon Marmont guessed that they had capitulated. With the forts gone, on 28 June Marmont began his retreat north to the Rio Douro by forced marches. In early July, Marmont was joined by Bonet's division, which gave him numbers equal to Wellington. By 15 July he massed 50,000 soldiers for another offensive. Perhaps the most important result of the siege was Marmont's underestimation of Wellington's generalship. Because Wellington remained passively on the defensive during the siege, Marmont, "thought he could take liberties with his opponent". This may have led to Marmont's defeat at the Battle of Salamanca on 22 July 1812.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 375.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 376.

- ↑ Glover 2001, pp. 188–190.

- ↑ Glover 2001, pp. 191–192.

- ↑ Oman 1996, p. 352.

- 1 2 Glover 2001, pp. 380–381.

- ↑ Oman 1996, p. 353.

- 1 2 Oman 1996, p. 354.

- ↑ Glover 2001, p. 391.

- ↑ Oman 1996, p. 355.

- ↑ Oman 1996, pp. 356–357.

- ↑ Oman 1996, pp. 359–360.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Oman 1996, pp. 361–362.

- 1 2 3 4 Oman 1996, pp. 363–364.

- ↑ Oman 1996, pp. 365–366.

- ↑ Oman 1996, pp. 367–369.

- 1 2 3 Oman 1996, pp. 370–372.

- ↑ McGuigan & Burnham 2017, p. 56.

- ↑ Oman 1996, pp. 373–375.

- 1 2 Oman 1996, pp. 375–377.

- ↑ Oman 1996, pp. 377–378.

- ↑ Oman 1996, pp. 378–382.

References

- Glover, Michael (2001). The Peninsular War 1807-1814. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-141-39041-7.

- McGuigan, Ron; Burnham, Robert (2017). Wellington's Brigade Commanders: Peninsula and Waterloo. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-47385-079-8.

- Oman, Charles (1996) [1914]. A History of the Peninsular War Volume V. Vol. 5. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole. ISBN 1-85367-225-4.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

External links

Media related to Siege of the Salamanca forts at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Siege of the Salamanca forts at Wikimedia Commons