| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Avebury, Wiltshire, England |

| Part of | Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii |

| Reference | 373-002 |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

| Coordinates | 51°24′57″N 1°51′27″W / 51.4157°N 1.8574°W |

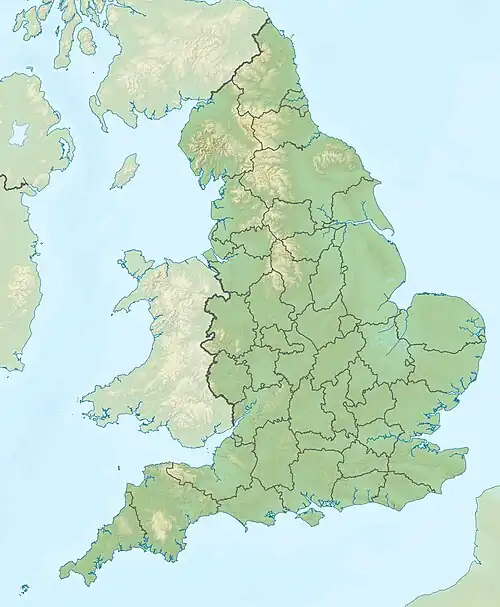

Location of Silbury Hill in England | |

Silbury Hill is a prehistoric artificial chalk mound near Avebury in the English county of Wiltshire. It is part of the Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites UNESCO World Heritage Site. At 39.3 metres (129 ft) high,[1] it is the tallest prehistoric human-made mound in Europe[2] and one of the largest in the world; similar in volume to contemporary Egyptian pyramids.[3][4]

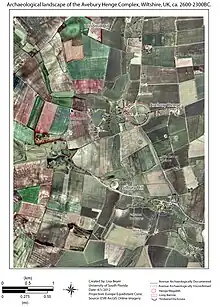

Silbury Hill is part of the complex of Neolithic monuments around Avebury, which includes the Avebury Ring and West Kennet Long Barrow. Its original purpose is still debated. Several other important Neolithic monuments in Wiltshire in the care of English Heritage, including the large henges at Marden and Stonehenge, may be culturally or functionally related to Avebury and Silbury.

Structure

Composed mainly of chalk and clay excavated from the surrounding area, the mound stands 40 metres (131 ft) high[5] and covers about 2 hectares (5 acres). The hill was constructed in several stages between c.2400–2300 BC[6] and displays immense technical skill and prolonged control over labour and resources. Archaeologists calculate that it took 18 million person-hours, equivalent to 500 people working for 15 years[7] to deposit and shape 248,000 cubic metres (324,000 cu yd) of earth and fill. Euan Mackie asserts that no simple late Neolithic tribal structure as usually imagined could have sustained this and similar projects, and envisages an authoritarian theocratic power elite with broad-ranging control across southern Britain.[8]

The base of the hill is circular and 167 metres (548 ft) in diameter. The summit is flat-topped and 30 metres (98 ft) in diameter. A smaller mound was constructed first, and in a later phase much enlarged. The initial structures at the base of the hill were perfectly circular: surveying reveals that the centre of the flat top and the centre of the cone that describes the hill lie within a metre of one another.[7] There are indications that the top originally had a rounded profile, but this was flattened in the medieval period to provide a base for a building, perhaps with a defensive purpose.[9]

The first clear evidence of construction, dated to around 2400 BC,[10] consisted of a gravel core with a revetting kerb of stakes and sarsen boulders. Alternate layers of chalk rubble and earth were placed on top of this: the second phase involved heaping further chalk on top of the core, using material excavated from a series of surrounding ditches which were progressively refilled then recut several metres further out.[6] The step surrounding the summit dates from this phase of construction, either as a precaution against slippage,[11] or as the remnants of a spiral path ascending from the base, used during construction to raise materials and later as a processional route.[12][10] Silbury Hill was originally entirely white due to a chalk (limestone) exterior, and the surrounding ditch may have been regularly filled with water from underground springs.[13]

Investigations

17th, 18th and 19th centuries

The site was first illustrated by the seventeenth-century antiquarian John Aubrey, whose notes, in the form of his Monumenta Britannica, were published between 1680 and 1682. Later, William Stukeley wrote that a skeleton and bridle had been discovered during tree planting on the summit in 1723. It is probable that this was a later, secondary burial. In October 1776 a team of Cornish miners overseen by the Duke of Northumberland and Colonel Edward Drax sank a vertical shaft from the top.[14] In 1849 a tunnel was dug horizontally from the edge into the centre. In 1867 the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society excavated the east side of the hill to see if traces of the Roman road were underneath it. No traces were found and later excavations south of the hill located the road in fields to the south, making a pronounced swerve to avoid the base of the hill. This was conclusive proof that the hill was there before the road – but the hill provided an alignment sight-line for the road.[15]

20th century

Flinders Petrie investigated the hill after the First World War. From 1968 to 1970 professor Richard J. C. Atkinson undertook work at Silbury which was broadcast on BBC Television. This excavation revealed most of the environmental evidence about the site, including the remains of winged ants which indicate that Silbury was begun in an August. Atkinson dug numerous trenches at the site and reopened the 1849 tunnel, where he found material suggesting a Neolithic date, although none of his radiocarbon dates are considered reliable by modern standards. He argued that the hill was constructed in steps, each tier being filled in with packed chalk and then smoothed off or weathered into a slope. Atkinson reported the C-14 date for the base layer of turf and decayed material indicated a corrected date for the commencement of Silbury was close to 2750 BC.[16]

21st century

After heavy rains in May 2002, a collapse of the 1776 excavation shaft caused a hole to form in the top of the hill. English Heritage undertook a seismic survey of the hill to identify the damage caused by earlier excavations and determine the hill's stability. Repairs were undertaken but the site remained closed to the public. As part of this remedial work English Heritage, with help from AC Archaeology excavated two further small trenches at the summit. Neil Adam from AC Archaeology made the important discovery of an antler fragment, the first from a secure archaeological context at the site. A radiocarbon date of c. 2490–2340 BC dates the second phase of the mound convincingly to the Late Neolithic.[12]

In March 2007, English Heritage announced that a Roman village had been found at the foot of Silbury Hill. It contained regularly laid out streets and houses.[17]

On 11 May 2007, contractors Skanska, under the overall direction of English Heritage,[9] began a major programme of stabilisation, filling the tunnels and shafts from previous investigations with hundreds of tonnes of chalk. At the same time a new archaeological survey was conducted using modern equipment and techniques.[18] The work finished in early 2008: a "significant" new understanding of the monument's construction and history had been obtained.[19]

In February 2010, letters written by Edward Drax concerning the 1776 excavation were found in the British Library describing a 40-foot (12 m) "perpendicular cavity" 6 inches (15 cm) wide. As wood fragments thought to be oak have been found it has been suggested that this may have held an oak tree or a "totem pole".[20]

Comparable sites

Following the 2007-8 works, archaeologists investigated whether Silbury Hill was the only such mound built by the people of the time, or if there might be other comparable mounds that have not been recognised as prehistoric. A strong candidate was felt to be the Marlborough Mound, in the grounds of Marlborough College, 8.3 kilometres (5.2 mi) east of Silbury Hill, further down the River Kennet. The mound is 18 metres (59 ft) high, less than half the height of Silbury. There are archaeological and documentary indications that the Marlborough Mound had been used for medieval fortifications, and it had been identified as a Norman motte. A team of archaeologists, led by Jim Leary, analysed core samples from two 10 cm diameter boreholes. Charcoal from immediately below the mound was from around 2500 BC, making it a close contemporary of Silbury.[21] Another contender, but which had been all-but levelled in the 19th century, was at Marden Henge, 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) south of Silbury. Known as Hatfield Barrow, a surviving fragment of what may have been a 15 m high mound also gave construction dates to the mid-third millennium BC.[21]

The Round Mound Project, to investigate other likely mounds, began in 2015, and from 154 potential sites across England, 20 were selected for core sampling and detailed surveying. By late 2017 fourteen had produced results confirming that they were built immediately after the Norman invasion of 1066. Three were shown to be later medieval mounds and one was from Saxon times, so may be a burial mound. Only one, Skipsea Castle mound in East Yorkshire, was found to be prehistoric, but dating to 800–400 BC, during the British Iron Age.[22] On the basis of this survey, it would appear that Neolithic mound-building was restricted to the upper Kennet and Avon valleys, and that nothing extant elsewhere in Britain comes close as a comparison to Silbury Hill.[22]

Artefacts

Few prehistoric artefacts have been found on Silbury Hill: at its core there is only clay, flints, turf, moss, topsoil, gravel, freshwater shells, mistletoe, oak, hazel, sarsen stones, ox bones, and antler tines. Roman and medieval items have been found on and around the site since the nineteenth century.

Purpose

The exact purpose of the hill is unknown, though various suggestions have been put forward.

Folklore

According to legend, Silbury is the last resting place of a King Sil, represented in a life-size gold statue and sitting on a golden horse. A local legend noted in 1913[23] states that the Devil was carrying a bag of soil to drop on the citizens of Marlborough, but he was stopped by the priests of nearby Avebury. In 1861 it was reported[24] that hundreds of people from Kennet, Avebury, Overton and the neighbouring villages thronged Silbury Hill every Palm Sunday.

Other suggestions

John C. Barret asserts that any ritual at Silbury Hill would have involved physically raising a few individuals far above the level of everyone else, where they would have been visible for miles around and from several other monuments in the area. This would possibly indicate an elite group, perhaps a priesthood, powerfully displaying their authority.[25]

Michael Dames has put forward a composite theory of seasonal rituals, in an attempt to explain the purpose of Silbury Hill and its associated sites (West Kennet Long Barrow, the Avebury henge, The Sanctuary and Windmill Hill), from which the summit of Silbury Hill is visible.[26]

Paul Devereux observes that Silbury and its surrounding monuments appear to have been designed with a system of inter-related sightlines, focusing on the step several metres below the summit. From various surrounding barrows and from Avebury, the step aligns with hills on the horizon behind Silbury, or with the hills in front of Silbury, leaving only the topmost part visible. In the latter case, Devereux hypothesises that ripe cereal crops grown on the intervening hill would perfectly cover the upper portion of Silbury, with the top of the corn and the top of Silbury coinciding.

Jim Leary and David Field (2010) conclude that the mound's purpose cannot be known, and the multiple and overlapping construction phases – almost continuous remodelling – suggest there was no blueprint and that the process of building was probably the most important thing of all: perhaps the process was more important than the hill.[27]

Location

Silbury Hill is in the Kennet valley, at grid reference SU099685. It is close to the A4, between Marlborough and Calne, and also near the route of a Roman road which runs between Beckhampton and West Kennet and passes to the south of the hill.

Site of Special Scientific Interest

The hill's vegetation is species-rich chalk grassland, dominated by upright brome and false oat-grass, but with many species characteristic of this habitat, including a strong population of the rare knapweed broomrape.[28] In 1965 and 1986 the entire hill – in all 2.3 hectares (5.7 acres) – was notified as a Site of Special Scientific Interest.[29]

See also

- Bell Beaker culture

- European Megalithic Culture

- Marlborough Mound

- Neolithic British Isles

- On Silbury Hill, a book by Adam Thorpe, published in 2014

- Silbury Air

References

- ↑ Historic England. "Silbury Hill (1008445)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ↑ Atkinson 1967.

- ↑ Malone (1989), p. 95.

- ↑ "Silbury Hill, Avebury". English Heritage.

- ↑ The measurement is taken from the present ground level at the top of silt that has accumulated in the trench surrounding the tumulus, to a depth of nine metres (Atkinson 1974:127).

- 1 2 Meirion Jones, Andrew (2012). Prehistoric Materialities: Becoming Material in Prehistoric Britain and Ireland. OUP. p. 181. ISBN 9780199556427.

- 1 2 Atkinson 1974 p. 128

- ↑ Mackie, Science and Society in Prehistoric Britain (New York: St. Martin's Press) 1977.

- 1 2 "Silbury Hill Conservation Project, Wiltshire". English Heritage. 2008. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 "Silbury Hill". National Monument Record. English Heritage. 2007. Archived from the original on 10 September 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- ↑ Darvill, Timothy (1996). Prehistoric Britain (2 ed.). London: Routledge. p. 93. ISBN 0-415-15135-X.

- 1 2 Field, David (May 2003). "Great sites: Silbury Hill". British Archaeology. York, England: Council for British Archaeology (70). ISSN 1357-4442.

- ↑ "Silbury Hill". Bradshaw Foundation.

- ↑ Hinman, Niki (2 February 2010). "Long lost theory on Silbury Hill is uncovered". The Wiltshire Gazette and Herald. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ↑ "Silbury Hill", BBC Publications 1969 – Refers to the excavations for the BBC TV programme dealing with the new 1968/1969 excavations for BBC2 TV programmes about the hill.

- ↑ 'Prehistoric Avebury' by Aubrey Burl, Yale University press, 1979, page 129

- ↑ "Silbury Hill reveals Roman settlement". Reuters. 10 March 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ↑ "Tunnel open again at Silbury hill". BBC News. 11 May 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ↑ Pitts, Mike (6 June 2008). "Silbury is safe". British Archaeology. York, England: Council for British Archaeology (101): 8. ISSN 1357-4442.

- ↑ "Silbury Hill 'built around pole'". BBC News. 3 February 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- 1 2 Leary, Jim; Marshall, Peter (December 2012). "The Giants of Wessex: the chronology of the three largest mounds in Wiltshire, UK". Antiquity. 86 (334). Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- 1 2 Jim Leary, Elaine Jamieson and Phil Stastney (2018). "Normal for Normans? Exploring the large round mounds of England". Current Archaeology (published April 2018) (337). Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ↑ Robt. M. Heanley, "Silbury Hill" Folklore 24.4 (December 1913), p. 524

- ↑ In Wilts Archaeological Magazine December 1861 p 181, noted by J. B. Partridge, "Wiltshire Folklore" Folklore 26.2 (June 1915), p 212.

- ↑ Barret, John. 1994. Fragments from Antiquity: An archaeology of social life in Britain 2900-1200BC. Blackwell, Oxford. pp29-31

- ↑ Dames, The Silbury Treasure

- ↑ Leary, Jim and Field, David, 2010 The Story Of Silbury Hill, English Heritage, Swindon

- ↑ "Citation sheet for the site" (PDF). Natural England. 1965. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ↑ "Silbury Hill SSSI". Natural England. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

Other references

- Atkinson, R.J.C., Antiquity 41 (1967)

- Atkinson, R.J.C., Antiquity 43 (1969), p 216.

- Atkinson, R.J.C., Antiquity 44(1970), pp 313–14.

- Atkinson, R.J.C., "Neolithic science and technology", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences (1974) pp. 127f.

- Dames, Michael, 1977 The Avebury Cycle Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

- Dames, Michael, 1976 The Silbury Treasure Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

- Dames, Michael, 2010 Silbury: Resolving the Enigma, The History Press, ISBN 978 0 7524 5450 4

- Devereux, Paul, 1999 Earth Memory: Practical Examples Introduce a New System to Unravel Ancient Secrets Foulsham

- Field, David (May 2003). "Great sites: Silbury Hill". British Archaeology magazine. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012 – via Internet Archive.

- Malone, Caroline (1989). Avebury. London: B T Batsford and English Heritage. ISBN 0-7134-5960-3.

- Leary, Jim and Field, David, 2010 The Story Of Silbury Hill, English Heritage, Swindon

- Oliver, Neil. 2012 A History of Ancient Britain. Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-2886-1

- Vatcher, Faith de M and Lance Vatcher, 1976 The Avebury Monuments, Department of the Environment HMSO