| Part of a series on |

| Slavery |

|---|

|

Slavery in the ancient world, from the earliest known recorded evidence in Sumer to the pre-medieval Antiquity Mediterranean cultures, comprised a mixture of debt-slavery, slavery as a punishment for crime, and the enslavement of prisoners of war. [1]

Masters could free slaves, and in many cases, such freedmen went on to rise to positions of power. This would include those children born into slavery, but who were actually the children of the master of the house. The slave master would ensure that his children were not condemned to a life of slavery.

The institution of slavery condemned a majority of slaves to agricultural and industrial labor, and they lived hard lives. In many of these cultures, slaves formed a very large part of the economy, and in particular the Roman Empire and some of the Greek poleis built a large part of their wealth on slaves acquired through conquest.

Near East

The Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest known surviving law code, written c. 2100 – 2050 BCE, includes laws relating to slaves during the Third Dynasty of Ur in Sumerian Mesopotamia. It states that a slave that marries cannot be forced to leave the household, and that the bounty for returning a slave who has escaped the city is two shekels. [2] It reveals that there were at least two major social strata at the time: those free, and those enslaved.

The Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, written between 1755–1750 BC, also distinguishes between the free and the enslaved. Like the Code of Ur-Nammu, it offers a reward of two shekels for returning a fugitive slave, but unlike the other code, states that harbouring or assisting a fugitive was punishable by death. Slaves were either bought abroad, taken as prisoners in war, or enslaved as a punishment for being in debt or committing a crime. The Code of Hammurabi states that if a slave is purchased and within one month develops epilepsy ("benu-disease") then the purchaser can return the slave and receive a full refund. The code has laws relating to the purchase of slaves abroad. Numerous contracts for the sale of slaves survive.[3] The final law in the Code of Hammurabi states that if a slave denies his master, then his ear will be cut off.[4][5]

Hittite texts from Anatolia include laws regulating the institution of slavery. Of particular interest is a law stipulating that reward for the capture of an escaped slave would be higher if the slave had already succeeded in crossing the Halys River and getting farther away from the center of Hittite civilization — from which it can be concluded that at least some of the slaves kept by the Hittites possessed a realistic chance of escaping and regaining their freedom, possibly by finding refuge with other kingdoms or ethnic groups.

In the Bible

In the Hebrew Bible (the Old Testament), there are many references to slaves, including rules of how they should behave and be treated. Slavery is viewed as routine, as an ordinary part of society. During jubilees, slaves were to be released, according to the Book of Leviticus.[6] Israelite slaves were also to be released during their seventh year of service, according to the Deuteronomic Code.[7] Non-Hebrew slaves and their offspring were the perpetual property of the owner's family,[8] with limited exceptions.[9] The Curse of Ham (Genesis 9:18–27) is an important passage related to slavery. It has been noted that the slavery in the Bible differs greatly from Roman and modern slavery in that slaves mentioned in the Old Testament received sexual protection and enough food, and were not chained, tortured or physically abused.[10]

In the New Testament, slaves are told to obey their owners, who are in turn told to "stop threatening" their slaves.[11][12] The Epistle to Philemon has many implications related to slavery.

Egypt

In Ancient Egypt, slaves were mainly obtained through prisoners of war. Other ways people could become slaves was by inheriting the status from their parents. One could also become a slave on account of his inability to pay his debts. Slavery was the direct result of poverty. People also sold themselves into slavery because they were poor peasants and needed food and shelter. Slaves only attempted escape when their treatment was unusually harsh. For many, being a slave in Egypt made them better off than a freeman elsewhere.[13] Young slaves could not be put to hard work and had to be brought up by the mistress of the household. Not all slaves went to houses. Some also sold themselves to temples or were assigned to temples by the king. Slave trading was not very popular until later in Ancient Egypt. Afterwards, slave trades sprang up all over Egypt. However, there was little worldwide trade. Rather, the individual dealers seem to have approached their customers personally.[13] Only slaves with special traits were traded worldwide. Prices of slaves changed with time. Slaves with a special skill were more valuable than those without one. Slaves had plenty of jobs that they could be assigned to. Some had domestic jobs, like taking care of children, cooking, brewing, or cleaning. Some were gardeners or field hands in stables. They could be craftsmen or even get a higher status. For example, if they could write, they could become a manager of the master's estate. Captive slaves were mostly assigned to the temples or a king, and they had to do manual labor. The worst thing that could happen to a slave was being assigned to the quarries and mines. Private ownership of slaves, captured in war and given by the king to their captor, certainly occurred at the beginning of the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550–1295 BCE). Sales of slaves occurred in the Twenty-fifth Dynasty (732–656 BCE), and contracts of servitude survive from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (c. 672 – 525 BCE) and from the reign of Darius: apparently such a contract then required the consent of the slave.

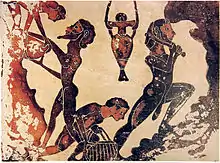

Greece

The study of slavery in Ancient Greece remains a complex subject, in part because of the many different levels of servility, from traditional chattel slave through various forms of serfdom, such as helots, penestai, and several other classes of non-citizens.

Most philosophers of classical antiquity defended slavery as a natural and necessary institution.[14] Aristotle believed that the practice of any manual or banausic job should disqualify the practitioner from citizenship. Quoting Euripides, Aristotle declared all non-Greeks slaves by birth, fit for nothing but obedience.

By the late 4th century BCE passages start to appear from other Greeks, especially in Athens, which opposed slavery and suggested that every person living in a city-state had the right to freedom subject to no one, except those laws decided using majoritarianism. Alcidamas, for example, said: "God has set everyone free. No one is made a slave by nature." Furthermore, a fragment of a poem of Philemon also shows that he opposed slavery.

Greece in pre-Roman times consisted of many independent city-states, each with its own laws. All of them permitted slavery, but the rules differed greatly from region to region. Greek slaves had some opportunities for emancipation, though all of these came at some cost to their masters. The law protected slaves, and though a slave's master had the right to beat him at will, a number of moral and cultural limitations existed on excessive use of force by masters.

In ancient Athens, about 10-30% of the population were slaves.[15][16] The system in Athens encouraged slaves to save up to purchase their freedom, and records survive of slaves operating businesses by themselves, making only a fixed tax-payment to their masters. Athens also had a law forbidding the striking of slaves—if a person struck an apparent slave in Athens, that person might find himself hitting a fellow-citizen, because many citizens dressed no better. It startled other Greeks that Athenians tolerated back-chat from slaves (Old Oligarch, Constitution of the Athenians). Pausanias (writing nearly seven centuries after the event) states that Athenian slaves fought together with Athenian freemen in the Battle of Marathon, and the monuments memorialize them.[17] Spartan serfs, Helots, could win freedom through bravery in battle. Plutarch mentions that during the Battle of Salamis Athenians did their best to save their "women, children and slaves".

On the other hand, much of the wealth of Athens came from its silver mines at Laurion, where slaves, working in extremely poor conditions, produced the greatest part of the silver (although recent excavations seem to suggest the presence of free workers at Laurion). During the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, twenty thousand Athenian slaves, including both mine-workers and artisans, escaped to the Spartans when their army camped at Decelea in 413 BC.

Other than flight, resistance on the part of slaves occurred only rarely. GEM de Ste. Croix gives two reasons:

- slaves came from various regions and spoke various languages

- a slave-holder could rely on the support of fellow slave-holders if his slaves offered resistance.

Athens had various categories of slave, such as:

- House-slaves, living in their master's home and working at home, on the land or in a shop.

- Freelance slaves, who didn't live with their master but worked in their master's shop or fields and paid him taxes from money they got from their own properties (insofar as society allowed slaves to own property).

- Public slaves, who worked as police-officers, ushers, secretaries, street-sweepers, etc.

- War-captives (andrapoda) who served primarily in unskilled tasks at which they could be chained: for example, rowers in commercial ships, or miners.

In some areas of Greece there existed a class of unfree laborers tied to the land and called penestae in Thessaly and helots in Sparta. Penestae and helots did not rate as chattel slaves; one could not freely buy and sell them.

The comedies of Menander show how the Athenians preferred to view a house-slave: as an enterprising and unscrupulous rascal, who must use his wits to profit from his master, rescue him from his troubles, or gain him the girl of his dreams. These plots were adapted by the Roman playwrights Plautus and Terence, and in the modern era influenced the character Jeeves and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.

Rome

Rome differed from Greek city-states in allowing freed slaves to become Roman citizens. After manumission, a slave who had belonged to a citizen enjoyed not only passive freedom from ownership, but active political freedom (libertas), including the right to vote, though he could not run for public office.[18] During the Republic, Roman military expansion was a major source of slaves. Besides manual labor, slaves performed many domestic services, and might be employed at highly skilled jobs and professions. Teachers, accountants, and physicians were often slaves. Greek slaves in particular might be highly educated. Unskilled slaves, or those condemned to slavery as punishment, worked on farms, in mines, and at mills.

See also

References

- ↑ "Ancient Slavery". Ditext.com. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- ↑ Roth, Martha. Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor. pp. 13–22.

- ↑ "A Collection of Contracts from Mesopotamia, c. 2300 - 428 BCE".

- ↑ Johns, Claude Hermann Walter. "BABYLONIAN LAW — The Code of Hammurabi". Eleventh Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, 1910-1911.

- ↑ King, L. W. "HAMMURABI'S CODE OF LAWS".

- ↑ Leviticus 25:8–13

- ↑ Deuteronomy 15:12

- ↑ Leviticus 25:44–47

- ↑ Exodus 21:26–27

- ↑ Williams, Peter J. (21 December 2015). "Does the Bible Support Slavery?". Be Thinking. Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ↑ Ephesians 6:5–9

- ↑ 1 Timothy 6:1

- 1 2 "Slaves and Slavery in Ancient Egypt". Touregypt.net. 2011-10-24. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- ↑ G.E.M. de Ste. Croix. The Class Struggle in the Ancient Greek World. pp. 409 ff. – Ch. VII, § ii The Theory of Natural Slavery.

- ↑ Hopkins, Keith (31 January 1981). Conquerors and Slaves. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-521-28181-2.

- ↑ "Confronting Slavery in the Classical World | Emory | Michael C. Carlos Museum". carlos.emory.edu. Retrieved 2023-07-15.

- ↑ Pausanias (1918). Description of Greece. Translated by Jones, W.H.S.; H.A. Ormerod. London: William Heinemann Ltd. ISBN 0-674-99328-4. OCLC 10818363.

- ↑ Fergus Millar, The Crowd in Rome in the Late Republic (University of Michigan, 1998, 2002), pp. 23, 209.