.jpg.webp) Royal Oak at anchor in 1937 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Royal Oak |

| Builder | Devonport Royal Dockyard |

| Cost | £2,468,269 |

| Laid down | 15 January 1914 |

| Launched | 17 November 1914 |

| Commissioned | 1 May 1916 |

| Identification | Pennant number: 08[1] |

| Nickname(s) | Mighty Oak[2] |

| Fate | Sunk by U-47, 14 October 1939 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | Revenge-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 620 ft 7 in (189.2 m) |

| Beam | 88 ft 6 in (27 m) |

| Draught | 33 ft 7 in (10.2 m) (Deep load) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 Shafts; 2 steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph) |

| Range | 7,000 nmi (12,960 km; 8,060 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Crew | 909 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour |

|

HMS Royal Oak was one of five Revenge-class battleships built for the Royal Navy during the First World War. Completed in 1916, the ship first saw combat at the Battle of Jutland as part of the Grand Fleet. In peacetime, she served in the Atlantic, Home and Mediterranean fleets, more than once coming under accidental attack. Royal Oak drew worldwide attention in 1928 when her senior officers were controversially court-martialled, an event that brought considerable embarrassment to what was then the world's largest navy. Attempts to modernise Royal Oak throughout her 25-year career could not fix her fundamental lack of speed and, by the start of the Second World War, she was no longer suitable for front-line duty.

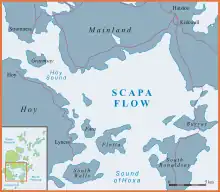

On 14 October 1939, Royal Oak was anchored at Scapa Flow in Orkney, Scotland, when she was torpedoed by the German submarine U-47. Of Royal Oak's complement of 1,234 men and boys, 835 were killed that night or died later of their wounds. The loss of the outdated ship—the first of five Royal Navy battleships and battlecruisers sunk in the Second World War—did little to affect the numerical superiority enjoyed by the British navy and its Allies, but it had a considerable effect on wartime morale. The raid made an immediate celebrity and war hero of the U-boat commander, Günther Prien, who became the first German submarine officer to be awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. Before the sinking of Royal Oak, the Royal Navy had considered the naval base at Scapa Flow impregnable to submarine attack, but U-47's raid demonstrated that the German navy was capable of bringing the war to British home waters. The shock resulted in rapid changes to dockland security and the construction of the Churchill Barriers around Scapa Flow, with the added advantage of being topped by roads running between the islands.

The wreck of Royal Oak, a designated war grave, lies almost upside down in 100 feet (30 m) of water with her hull 16 feet (4.9 m) beneath the surface. In an annual ceremony marking the loss of the ship, Royal Navy divers place a White Ensign underwater at her stern. Unauthorised divers are prohibited from approaching the wreck under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986.

Design and description

The Revenge-class ships were designed as slightly smaller, slower, and more heavily protected versions of the preceding Queen Elizabeth-class battleships. As an economy measure they were intended to revert to the previous practice of using both fuel oil and coal, but First Sea Lord Jackie Fisher rescinded the decision for coal in October 1914. While under construction the ships were redesigned to employ oil-fired boilers that increased the power of the engines by 9,000 shaft horsepower (6,700 kW) over the original specification.[3]

_profile_drawing.png.webp)

Royal Oak had a length overall of 620 feet 7 inches (189.2 m), a beam of 88 feet 6 inches (27 m) and a deep draught of 33 feet 7 inches (10.2 m). She had a designed displacement of 27,790 long tons (28,240 t) and displaced 31,130 long tons (31,630 t) at deep load. She was powered by two sets of Parsons steam turbines, each driving two shafts, using steam from 18 Yarrow boilers. The turbines were rated at 40,000 shaft horsepower (30,000 kW) and intended to reach a maximum speed of 23 knots (42.6 km/h; 26.5 mph). During her sea trials on 22 May 1916, the ship reached a top speed of only 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph) from 40,360 shp (30,100 kW).[4] She had a range of 7,000 nautical miles (12,964 km; 8,055 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (18.5 km/h; 11.5 mph).[5] Her crew numbered 909 officers and ratings in 1916.[6]

The Revenge class was equipped with eight breech-loading (BL) 15-inch (381 mm) Mk I guns in four twin gun turrets, in two superfiring pairs fore and aft of the superstructure, designated 'A', 'B', 'X', and 'Y' from front to rear. Twelve of the fourteen BL 6-inch (152 mm) Mk XII guns were mounted in casemates along the broadside of the vessel amidships; the remaining pair were mounted on the shelter deck and were protected by gun shields. Their anti-aircraft (AA) armament consisted of two quick-firing (QF) 3-inch (76 mm) 20 cwt Mk I[lower-alpha 1] guns. The ships were fitted with four submerged 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes, two on each broadside.[7]

Royal Oak was completed with two fire-control directors fitted with 15-foot (4.6 m) rangefinders. One was mounted above the conning tower, protected by an armoured hood, and the other was in the spotting top above the tripod foremast. Each turret was also fitted with a 15-foot rangefinder. The main armament could also be controlled by 'X' turret. The secondary armament was primarily controlled by directors mounted on each side of the compass platform on the foremast once they were fitted in March 1917.[8] A torpedo-control director with a 15-foot rangefinder was mounted at the aft end of the superstructure.[9]

The ship's waterline belt consisted of Krupp cemented armour (KC) that was 13 inches (330 mm) thick between 'A' and 'Y' barbettes and thinned to 4 to 6 inches (100 to 150 millimetres) towards the ship's ends, but did not reach either the bow or the stern. Above this was a strake of armour 6 inches thick that extended between 'A' and 'X' barbettes. Transverse bulkheads 4 to 6 inches thick ran at an angle from the ends of the thickest part of the waterline belt to 'A' and 'Y' barbettes.[10] The gun turrets were protected by 11 to 13 inches (279 to 330 mm) of KC armour, except for the turret roofs which were 4.75–5 inches (121–127 mm) thick. The barbettes ranged in thickness from 6–10 inches (152–254 mm) above the upper deck, but were only 4 to 6 inches thick below it. The Revenge-class ships had multiple armoured decks that ranged from 1 to 4 inches (25 to 102 mm) in thickness.[11] The main conning tower had 13 inches of armour on the sides with a 3-inch roof. The torpedo director in the rear superstructure had 6 inches of armour protecting it.[12] After the Battle of Jutland, 1 inch of high-tensile steel was added to the main deck over the magazines and additional anti-flash equipment was installed in the magazines.[13]

The ship was fitted with flying-off platforms, mounted on the roofs of 'B' and 'X' turrets, in 1918; from which fighters and reconnaissance aircraft could launch. In 1934 the platforms were removed from the turrets and a catapult was installed on the roof of 'X' turret, along with a crane to recover a seaplane.[14]

Major alterations

Royal Oak was extensively refitted between 1922 and 1924, when her anti-aircraft defences were upgraded by replacing the original three-inch AA guns with a pair of QF four-inch (102 mm) Mk V AA guns.[15] A 30-foot (9.1 m) rangefinder[13] was fitted in 'B' turret and a simple high-angle rangefinder was added above the bridge.[15] Underwater protection improved by the addition of anti-torpedo bulges. They were designed to reduce the effect of torpedo detonations and improve stability at the cost of widening the ship's beam by over 13 feet (4.0 m).[16] They increased her beam to 102 feet 1 inch (31.1 m), reduced her draught to 29 feet 6 inches (9 m),[17] increased her metacentric height to 6.3 feet (1.9 m) at deep load,[15] and all the changes to her equipment increased her crew to a total of 1,188. Despite the bulges she was able to reach a speed of 21.75 knots (40.28 km/h; 25.03 mph).[17] A brief refit in early 1927 saw the addition of two more four-inch AA guns and the removal of the six-inch guns from the shelter deck.[18] About 1931, a High-Angle Control System (HACS) Mk I director replaced the high-angle rangefinder on the spotting top. Two years later, the aft pair of torpedo tubes were removed.[17]

The ship received a final refit between 1934 and 1936, when her deck armour was increased to 5 inches (13 cm) over the magazines and to 3.5 inches (8.9 cm) over the engine rooms. In addition to a general modernisation of the ship's systems, her anti-aircraft defences were strengthened by replacing the single mounts of the AA guns with twin mounts for the QF 4-inch Mark XVI gun and adding a pair of octuple mounts for two-pounder Mk VIII "pom-pom" guns to sponsons abreast the funnel.[16] Two positions for "pom-pom" anti-aircraft directors were added on new platforms abreast and below the fire-control director in the spotting top. A HACS Mk III director replaced the Mk I in the spotting top and another replaced the torpedo director aft. A pair of quadruple mounts for Vickers .50 machine guns were added abreast the conning tower. The mainmast was reconstructed as a tripod to support the weight of a radio-direction finding office and a second High-Angle Control Station.[19] The forward pair of submerged torpedo tubes were removed and four experimental 21-inch torpedo tubes were added above water forward of 'A' turret.[20]

Construction and service

Royal Oak was laid down at Devonport Royal Dockyard on 15 January 1914. She was launched on 17 November, and after fitting-out was commissioned on 1 May 1916 at a final cost of £2,468,269.[21] Named after the Royal Oak in which Charles II hid following his defeat at the 1651 Battle of Worcester, she was the eighth vessel to bear the name Royal Oak, replacing a pre-dreadnought scrapped in 1914.[22] Upon completion Royal Oak was assigned to the Third Division of the Fourth Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet, under the command of Captain Crawford Maclachlan.[23]

First World War

Battle of Jutland

In an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet, the German High Seas Fleet, composed of 16 dreadnoughts, 6 pre-dreadnoughts, 6 light cruisers, and 31 torpedo boats, departed the Jade early on the morning of 31 May. The fleet sailed in concert with Rear-Admiral Franz von Hipper's five battlecruisers and supporting cruisers and torpedo boats. The Royal Navy's Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. The Admiralty ordered Admiral John Jellicoe, commander of the Grand Fleet – totalling 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers – to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[24] The initial action was fought primarily by the British and German battlecruiser formations in the afternoon, but by 18:00 the Grand Fleet approached the scene.[25] Fifteen minutes later, Jellicoe gave the order to turn and deploy the fleet for action.[26]

The German cruiser SMS Wiesbaden had become disabled by British shellfire, and both sides concentrated in the area, the Germans trying to protect their cruiser and the British attempting to sink her. At 18:29, Royal Oak opened fire on the German cruiser, firing four salvoes from her main guns in quick succession, along with her secondary battery. She scored a hit on Wiesbaden aft with her third salvo. In return, Royal Oak was straddled by a German salvo at 18:33 but was undamaged.[27] German torpedo boats attempted to reach Wiesbaden shortly after 19:00, and at 19:07, Royal Oak's secondary guns opened fire on them, believing they were instead trying to launch a torpedo attack.[28] By 19:15, Royal Oak's gunners had observed the German battlecruiser squadron and opened fire at the leading vessel, SMS Derfflinger. The gunners overestimated the range initially, but by 19:20 had found the correct distance and scored a pair of hits aft, which did not inflict serious damage. Derfflinger then disappeared in the haze, so Royal Oak shifted fire to the next battlecruiser, SMS Seydlitz. She scored a hit at 19:27 before Seydlitz too was lost in the mist.[29]

While Royal Oak was attacking the battlecruisers, a German torpedo boat flotilla launched an attack on the British battleline. Royal Oak's secondary guns were the first to open fire, at 19:16, followed quickly by the rest of the British ships.[30] Following the German destroyer attack, the High Seas Fleet disengaged, and Royal Oak and the rest of the Grand Fleet saw no further action in the battle. This was, in part, due to confusion aboard the fleet flagship over the exact location and course of the German fleet; without this information, Jellicoe could not bring his fleet to action. At 21:30, the Grand Fleet began to reorganise into its night-time cruising formation.[31] Early on the morning of 1 June, the Grand Fleet combed the area, looking for damaged German ships, but after spending several hours searching, they found none.[32] In the course of the battle, Royal Oak had fired 38 rounds from her main battery and 84 rounds from her secondary guns.[33]

Later actions

Following the battle, Royal Oak was reassigned to the First Battle Squadron. On 18 August, the Germans again sortied, this time to bombard Sunderland; Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, the German fleet commander, hoped to draw out the British battlecruisers and destroy them. British signals intelligence decrypted German wireless transmissions, allowing Jellicoe enough time to deploy the Grand Fleet in an attempt to engage in a decisive battle. Both sides withdrew after their opponents' submarines inflicted losses in the action of 19 August 1916: the British cruisers Nottingham and Falmouth were both torpedoed and sunk by German U-boats, and the German battleship SMS Westfalen was damaged by the British submarine E23. After returning to port, Jellicoe issued an order that prohibited risking the fleet in the southern half of the North Sea due to the overwhelming risk from mines and U-boats.[34] In late 1917, the Germans began using destroyers and light cruisers to raid the British convoys to Norway; this forced the British to deploy capital ships to protect the convoys. In April 1918, the German fleet sortied in an attempt to catch one of the isolated British squadrons, though the convoy had already passed safely. The Grand Fleet sortied too late to catch the retreating Germans, although the battlecruiser SMS Moltke was torpedoed and badly damaged by the submarine HMS E42.[35]

On 5 November 1918, in the final week of the First World War, Royal Oak was anchored off Burntisland in the Firth of Forth accompanied by the seaplane tender Campania and the light battlecruiser Glorious. A sudden Force 10 squall caused Campania to drag her anchor, collide with Royal Oak and then with Glorious. Both capital ships suffered only minor damage, but Campania was holed by her initial collision with Royal Oak. The ship's engine rooms flooded, and she settled by the stern and sank five hours later, without loss of life.[36]

Following the capitulation of Germany in November 1918, the Allies interned most of the High Seas Fleet at Scapa Flow. The fleet rendezvoused with the British light cruiser Cardiff, which led the ships to the Allied fleet that was to escort the Germans to Scapa Flow. The fleet consisted of 370 British, American, and French warships. The High Seas Fleet remained in captivity during the negotiations that ultimately produced the Treaty of Versailles. Konteradmiral Ludwig von Reuter believed the British intended to seize the German ships on 21 June 1919, which was the deadline for Germany to have signed the peace treaty. That morning, the Grand Fleet left Scapa Flow to conduct training manoeuvres, and while they were away von Reuter issued the order to scuttle the High Seas Fleet.[37]

1920s

The peacetime reorganisation of the Royal Navy assigned Royal Oak to the Second Battle Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet. Modernised by a 1922–24 refit, she was transferred in 1926 to the Mediterranean Fleet, based in Grand Harbour, Malta. In early 1928, this duty saw a notorious incident which the contemporary press dubbed the "Royal Oak Mutiny".[38] What began as a simple dispute between Rear-Admiral Bernard Collard and Royal Oak's two senior officers, Captain Kenneth Dewar and Commander Henry Daniel, over the band at the ship's wardroom dance,[lower-alpha 2] descended into a bitter personal feud that spanned several months.[40] Dewar and Daniel accused Collard of "vindictive fault-finding" and openly humiliating and insulting them before their crew; in return, Collard countercharged the two with failing to follow orders and treating him "worse than a midshipman".[41]

When Dewar and Daniel wrote letters of complaint to Collard's superior, Vice-Admiral John Kelly, he immediately passed them on to the Commander-in-Chief Admiral Sir Roger Keyes. On realising that the relationship between the two and their flag admiral had irretrievably broken down, Keyes hurriedly convened a Board of Enquiry, the outcome of which was to remove all three men from their posts and send them back to England.[42] The Board sat on the eve of a major naval exercise, which Keyes was obliged to postpone, causing rumours to fly around the fleet that the Royal Oak had experienced a mutiny. The story was picked up by the press worldwide, which described the affair with some hyperbole.[43] Public attention reached such proportions as to raise the concerns of the King, who summoned First Lord of the Admiralty William Bridgeman for an explanation.[43]

For their letters of complaint, Dewar and Daniel were controversially charged with writing "subversive documents".[44] In a pair of highly publicised courts-martial held in Gibraltar, both were found guilty and severely reprimanded, leading Daniel to resign from the Navy. Collard himself was criticised for the excesses of his conduct by the press and in Parliament, and on being denounced by Bridgeman as "unfitted to hold further high command",[45] was forcibly retired from service.[46] Of the three, only Dewar escaped with his career, albeit a damaged one: he remained in the Royal Navy, but in a series of more minor commands.[47] His promotion to rear-admiral, which would normally have been a formality, was delayed until the following year, just one day before his retirement.[48] Daniel attempted a career in journalism, but when this and other ventures were unsuccessful, he disappeared into obscurity amid poor health in South Africa.[49] Collard retreated to private life and never spoke publicly of the incident again. On the retired list, he was promoted from Rear- to Vice-Admiral on 1 April 1931.[50]

The scandal proved an embarrassment to the reputation of the Royal Navy, then the world's largest, and it was satirised at home and abroad through editorials, cartoons,[51] and even a comic jazz oratorio composed by Erwin Schulhoff.[52] One consequence of the damaging affair was an undertaking from the Admiralty to review the means by which naval officers might bring complaints against the conduct of their superiors.[45]

1930s

During the Spanish Civil War, Royal Oak was tasked with conducting non-intervention patrols around the Iberian Peninsula. On such a patrol and steaming 30 nautical miles (56 km; 35 mi) east of Gibraltar on 2 February 1937, she came under aerial attack by three aircraft of the Republican forces. They dropped three bombs (two of which exploded) within 3 cables (550 m) of the starboard bow, causing no damage.[53] The British chargé d'affaires protested about the incident to the Republican Government, which admitted its error and apologised for the attack.[54][55] Later that same month, while stationed off Valencia on 23 February 1937 during an aerial bombardment by the Nationalists, she was accidentally struck by an anti-aircraft shell fired from a Republican position.[53] Five men were injured, including Royal Oak's captain, T. B. Drew.[56] On this occasion the British did not protest to the Republicans, deeming the incident "an act of God".[57]

In May 1937, she and HMS Forester escorted SS Habana, an ocean liner carrying thousands of Basque child refugees, to the Southampton Docks.[58] In July, as the war in northern Spain flared up, Royal Oak, along with her sister HMS Resolution rescued the steamer Gordonia when Spanish Nationalist warships attempted to capture her off Santander. She was unable on 14 July to prevent the seizure of the British freighter Molton by the Nationalist cruiser Almirante Cervera while trying to enter Santander. The merchantmen had been engaged in the evacuation of refugees.[59]

This same period saw Royal Oak star alongside fourteen other Royal Navy vessels in the 1937 British film melodrama Our Fighting Navy, the plot of which centres around a coup in the fictional South American republic of Bianco. The Royal Navy saw the film as a recruitment opportunity and provided warships and extras. Royal Oak portrays a rebel battleship El Mirante, whose commander forces a British captain (played by Robert Douglas) into choosing between his lover and his duty.[60] The film was poorly received by critics, but gained some redemption through its dramatic scenes of naval action.[61]

In 1938, Royal Oak returned to the Home Fleet and was made flagship of the Second Battle Squadron based in Portsmouth. On 24 November 1938, she returned the body of the British-born Queen Maud of Norway, who had died in London, to Oslo for a state funeral, accompanied by her husband King Haakon VII.[62] Paying off in December 1938, Royal Oak was recommissioned the following June, and in 1939 embarked on a short training cruise in the English Channel in preparation for another 30-month tour of the Mediterranean,[63] for which her crew were issued tropical uniforms.[64] As hostilities loomed, the battleship was instead dispatched north to Scapa Flow, and was at anchor there when war was declared on 3 September.[63]

Second World War

The next few weeks of the Phoney War proved uneventful, but in October 1939 Royal Oak joined the search for the German battleship Gneisenau, which had been ordered into the North Sea as a diversion for the commerce-raiding heavy cruisers Deutschland and Admiral Graf Spee.[65] The search was ultimately fruitless, particularly for Royal Oak, whose top speed, by then less than 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), was inadequate to keep up with the rest of the fleet.[65] On 12 October, Royal Oak returned to the defences of Scapa Flow in poor shape, battered by North Atlantic storms. Many of her Carley Floats had been smashed and several of the smaller-calibre guns rendered inoperable through flooding.[65][66] The mission had underlined the obsolescence of the 25-year-old warship.[65][67] Concerned that a recent overflight by German reconnaissance aircraft heralded an imminent air attack upon Scapa Flow, Admiral of the Home Fleet Charles Forbes ordered most of the fleet to disperse to safer ports. Royal Oak remained behind, her anti-aircraft guns still deemed a useful addition to Scapa's otherwise scanty air defences.[66]

Sinking

Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow made a near-ideal anchorage. Situated at the centre of the Orkney Islands off the north coast of Scotland, the natural harbour, large enough to contain the entire Grand Fleet,[68] was surrounded by a ring of islands separated by shallow channels subject to fast-racing tides. That U-boats still posed a threat had long been realised, and a series of countermeasures were installed during the early years of the First World War.[69] Blockships were sunk at critical points; and floating booms deployed to block the three widest channels, operated by tugboats to allow the passage of friendly shipping. It was considered possible, but highly unlikely, that a U-boat commander might attempt to race through undetected before the boom was closed.[69] Two submarines unsuccessfully attempted infiltration during the First World War: on 23 November 1914 U-18 was rammed twice before running aground with the capture of her crew,[70][71] and UB-116 was detected by hydrophone and destroyed with the loss of all hands on 28 October 1918.[72][73]

Scapa Flow provided the main anchorage for the British Grand Fleet throughout most of the First World War, but in the interwar period this passed to Rosyth, further south in the Firth of Forth.[69][74] Scapa Flow was reactivated with the advent of the Second World War, becoming a base for the British Home Fleet.[69] Its natural and artificial defences, while still strong, were recognised as in need of improvement, and in the early weeks of the war were in the process of being strengthened by the provision of additional blockships.[75]

Special Operation P: the raid by U-47

Kriegsmarine Commander of Submarines (Befehlshaber der U-Boote) Karl Dönitz devised a plan to attack Scapa Flow by submarine within days of the outbreak of war.[76] Its goal would be twofold: first, displacing the Home Fleet from Scapa Flow would slacken the British North Sea blockade and grant Germany greater freedom to attack the Atlantic convoys; second, the blow would be a symbolic act of vengeance, striking at the same location where the German High Seas Fleet had scuttled itself following Germany's defeat in the First World War. Dönitz hand-picked Kapitänleutnant Günther Prien for the task,[76][lower-alpha 3] scheduling the raid for the night of 13/14 October 1939, when the tides would be high and the night moonless.[76]

Dönitz was aided by high-quality photographs from a reconnaissance overflight by Siegfried Knemeyer (who received his first Iron Cross for the mission), which revealed the weaknesses of the defences and an abundance of targets.[76] He directed Prien to enter Scapa Flow from the east via Kirk Sound, passing to the north of Lamb Holm, a small, low-lying island between Burray and Mainland.[77] Prien initially mistook the more southerly Skerry Sound for the chosen route, and his sudden realisation that U-47 was heading for the shallow blocked passage forced him to order a rapid turn to the northeast.[78] On the surface, and illuminated by a bright display of the aurora borealis,[79] the submarine threaded between the sunken blockships Seriano and Numidian, grounding itself temporarily on a cable strung from Seriano.[77] It was briefly caught in the headlights of a taxi onshore, but the driver raised no alarm.[80][lower-alpha 4] On entering the harbour proper at 00:27 on 14 October, Prien entered a triumphant Wir sind in Scapa Flow!!![lower-alpha 5] in the log and set a south-westerly course for several kilometres before reversing direction.[77] To his surprise, the anchorage appeared to be almost empty; unknown to him, Forbes's order to disperse the fleet had removed some of the biggest targets. U-47 had been heading directly towards four warships, including the newly commissioned light cruiser Belfast, anchored off Flotta and Hoy 4 nautical miles (7.4 kilometres; 4.6 miles) distant, but Prien gave no indication he had seen them.[81]

On the reverse course, a lookout on the bridge spotted Royal Oak lying approximately 4,400 yards (4,000 m) to the north, correctly identifying her as a battleship of the Revenge class. Mostly hidden behind her was a second ship, only the bow of which was visible to U-47. Prien mistook her to be a battlecruiser of the Renown class, German intelligence later labelling her Repulse.[77] She was in fact the World War I seaplane tender Pegasus.[82]

At 00:58 U-47 fired a salvo of three torpedoes from its bow tubes, a fourth lodging in its tube. Two failed to find a target, but a single torpedo struck the bow of Royal Oak at 01:04, shaking the ship and waking the crew.[83] There was little visible damage, but the starboard anchor chain had been severed, clattering noisily down through its slips. Initially, it was suspected that there had been an explosion in the ship's forward inflammable store, used to store materials such as kerosene. Mindful of the unexplained explosion that had destroyed HMS Vanguard at Scapa Flow in 1917,[71][lower-alpha 6] an announcement was made over Royal Oak's tannoy system to check the magazine temperatures,[lower-alpha 7] but many sailors returned to their hammocks, unaware the ship was under attack.[83][87]

Prien turned his submarine and attempted another shot via his stern tube, but this too missed. Reloading his bow tubes, he doubled back and fired a salvo of three torpedoes, all at Royal Oak.[77] This time he was successful. At 01:16, all three struck the battleship in quick succession amidships and detonated.[88][89] The explosions blew a hole in the armoured deck, destroying the Stokers', Boys' and Marines' messes and causing a loss of electrical power.[90] Cordite from a magazine ignited and the ensuing fireball passed rapidly through the ship's internal spaces.[90] Royal Oak quickly listed to 15°, sufficient to push the open starboard-side portholes below the waterline.[lower-alpha 8] She soon rolled further onto her side to 45°, hanging there for several minutes before disappearing beneath the surface at 01:29, 13 minutes after Prien's second strike.[92] 835 men died with the ship or died later of their wounds.[lower-alpha 9] The dead included Rear-Admiral Henry Blagrove, commander of the Second Battle Squadron. 134 of the dead were boy seamen, not yet 18 years old, the largest ever such loss in a single Royal Navy action.[94]

Rescue efforts

The tender Daisy 2, skippered by John Gatt, had been tied up for the night to Royal Oak's port side. As the sinking battleship began to list to starboard, Gatt ordered Daisy 2 to be cut loose, his vessel becoming briefly caught on Royal Oak's rising anti-torpedo bulge and lifted from the sea before freeing herself.[95]

Many of Royal Oak's crew who had managed to jump from the sinking ship were dressed in little more than their nightclothes and were unprepared for the chilling water. A thick layer of fuel oil coated the surface, filling men's lungs and stomachs and hampering their efforts to swim. Of those who attempted the half-mile (800 m) swim to the nearest shore, only a handful survived.[96]

Royal Oak's port side pinnace was manoeuvred away from the sinking ship and paddled away using wooden boards as there had been insufficient time to raise steam. The boat became overladen and capsized 300 metres from Royal Oak, throwing those on deck into the water and trapping those below.[97][lower-alpha 10]

Gatt switched the lights of Daisy 2 on and he and his crew managed to pull 386 men from the water, including Royal Oak's commander, Captain William Benn.[98] The rescue efforts continued for another two and a half hours until nearly 4:00 am, when Gatt abandoned the search for more survivors and took those he had to Pegasus. Aided by boats from Pegasus and the harbour,[99] he was responsible for rescuing almost all the survivors, an act for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross,[100] the only military award made by the British in connection with the disaster.[101] Pegasus had sent a message by signal lamp to the port signal station about five minutes after the sinking, saying "General. Send all boats", and half an hour later "Royal Oak is sinking after several internal explosions".[102] The total number of survivors was 424.[103]

Aftermath

The British were initially confused as to the cause of the sinking, suspecting either an on-board explosion or aerial attack.[69] Once it was realised that a submarine attack was the most likely explanation, steps were rapidly made to seal the anchorage, but U-47 had already escaped and was on its way back to Germany. The BBC released news of the sinking by late morning on 14 October, and its broadcasts were received by the German listening services and by U-47 itself. Divers sent down on the morning after the explosion discovered remnants of a German torpedo, confirming the means of attack. On 17 October, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill officially announced the loss of Royal Oak to the House of Commons, first conceding that the raid had been "a remarkable exploit of professional skill and daring", but then declaring that the loss would not materially affect the naval balance of power.[104] An Admiralty board of inquiry convened between 18 and 24 October to establish the circumstances under which the anchorage had been penetrated. In the meantime, the Home Fleet was ordered to remain at safer ports until security issues at Scapa could be addressed.[105] Churchill was obliged to respond to questions in the House as to why Royal Oak had had aboard so many boys,[106] most of whom died. He defended the Royal Navy tradition of sending boys aged 15 to 17 to sea, but the practice was generally discontinued shortly after the disaster, and under 18-year-olds served on active warships in only the most exceptional circumstances.[94]

The Nazi Propaganda Ministry was quick to capitalise on the successful raid,[107][108] and radio broadcasts by the popular journalist Hans Fritzsche displayed the triumph felt throughout Germany.[109] Prien and his crew reached Wilhelmshaven at 11:44 on 17 October and were immediately greeted as heroes, learning that Prien had been awarded the Iron Cross First Class, and each man of the crew the Iron Cross Second Class.[110] Hitler sent his personal plane to bring the crew to Berlin, where he further invested Prien with the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.[111] This decoration, made for the first time to a German submarine officer, later became the customary decoration for successful U-boat commanders. Dönitz was rewarded by promotion from Commodore to Rear-Admiral and was made Flag Officer of U-boats.[110]

Prien was nicknamed "The Bull of Scapa Flow" and his crew decorated U-47's conning tower with a snorting bull mascot, later adopted as the emblem of the 7th U-boat Flotilla. He found himself in demand for radio and newspaper interviews,[110] and his 'autobiography' was published the following year, titled Mein Weg nach Scapa Flow.[lower-alpha 11] Ghost-written for him by a journalist, Paul Weymar, following some brief interviews with Prien in March and April 1940, the manuscript was edited by the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (the German high command) and the Reich Ministry of Propaganda. It was intended as an adventure story for boys.[112] When Prien received a copy of the book, he angrily made numerous corrections to the text, and when an English translation of the book was published in 1955, Weymar wrote a letter of protest to the British publisher saying that the "demonstrably false" account should not have been published out of context and he donated his royalties to charity.[113][114]

The Admiralty Board of Inquiry's president was Admiral Reginald Plunkett-Ernle-Erle-Drax, assisted by Admiral Robert Raikes and Captain Gerard Muirhead-Gould.[115] Their official report into the disaster condemned the defences at Scapa Flow, and censured Sir Wilfred French, Admiral Commanding, Orkneys and Shetlands, for their unprepared state. French was placed on the retired list,[116] despite having warned the previous year of Scapa Flow's deficient anti-submarine defences, and volunteering to bring a small ship or submarine himself past the blockships to prove his point.[117] On Churchill's orders, the eastern approaches to Scapa Flow were sealed with concrete causeways linking Lamb Holm, Glimps Holm, Burray and South Ronaldsay to Mainland. Constructed largely by Italian prisoners of war, the Churchill Barriers, as they became known, were essentially complete by September 1944, and were opened officially just after VE Day in May 1945.[118]

In a second report, the Board of Inquiry considered the actual sinking of Royal Oak and the resulting loss of life, which having been in port and in calm water was thought to be "very heavy". The report concluded that the main cause was due to an unusually high number of men having been below the main armoured deck because they had been sent to air defence stations. Their escape was slowed because of the number of watertight doors which were closed. The question of "deadlights" was also considered; these were ventilated metal plates that replaced the glass panes in the scuttles or portholes when ships were in port, allowing the wartime blackout to be observed. It was thought that water flooding through these had hastened the initial heeling over, but having the ventilators closed would not have saved the ship.[119]

In the years that followed, a rumour circulated that Prien had been guided into Scapa by Alfred Wehring, a German agent living in Orkney in the guise of a Swiss watchmaker named Albert Oertel;[120] following the attack, 'Oertel' supposedly escaped in the submarine B-06 to Germany.[121] This account of events originated as an article by the journalist Curt Riess in the 16 May 1942 issue of the American magazine Saturday Evening Post and was later embellished by other authors.[120][122] Post-war searches through German and Orcadian archives have failed to find any evidence for the existence of Oertel, Wehring or a submarine named B-06, and the story is now held to be wholly fictitious.[123][124] In 1959, the Orkneys' preeminent watchmaker, Mr E. W. Hourton, informed "with the utmost assurance" the editor of The Orkney Herald that in his lifetime there had never been a watchmaker named Oertel in Kirkwall nor anyone resembling such a person.[121] Orkney's chief librarian, in a 1983 letter to the historian Nigel West, suggested that the name Albert Oertel was likely a pun on the well-known Albert Hotel in Kirkwall.[120]

Survivors

In the immediate aftermath of the sinking, Royal Oak's survivors were billeted in the towns and villages of Orkney. A funeral parade for the dead took place at Lyness on Hoy on 16 October; many of the surviving crew, having lost all their own clothing on the ship, attended in borrowed boiler suits and gym shoes.[125] They were generally granted a few days survivors' leave by the navy, and then assigned to ships and roles elsewhere.[126]

Prien did not survive the war: he and U-47 were lost on 7 March 1941, possibly as a result of an attack by the British destroyer HMS Wolverine.[127] News of the loss was kept secret by the Nazi government for ten weeks.[128] Several U-47 crew from the Royal Oak mission did survive, having been transferred to other vessels. Some of them subsequently met with their former enemies from Royal Oak and forged friendships with them.[129][lower-alpha 12]

The HMS Royal Oak Association holds an Act of Remembrance annually at Portsmouth, the Royal Oak's home port, on the Saturday nearest to 13 October; originally at the Naval Memorial at Southsea,[130] but in later years at St Ann's Church, Portsmouth Naval Base. At the service on 9 October 2019, eighty years after the sinking, a memorial stone was unveiled in the church by Anne, Princess Royal, the Commodore-in-Chief of HMNB Portsmouth. Some one hundred and fifty relatives and descendants of the crew were in attendance.[131]

Kenneth Toop, who survived the sinking while serving as a boy, first class, on Royal Oak, served as the Association's honorary secretary for fifteen years.[132] The last remaining survivor of Royal Oak, Arthur Smith, died on 11 December 2016. Serving as a 17-year-old boy, first class, he had been on watch on the bridge when the ship was struck and jumped from the sinking vessel, swimming in the wrong direction until he was picked up by a boat and transferred to the Daisy 2.[133]

Wreck

Status as war grave

Despite the relatively shallow water in which she sank, the majority of bodies could not be recovered from Royal Oak. Marked by a buoy at 58°55′44″N 2°59′09″W / 58.92889°N 2.98583°W, the wreck has been designated a war grave and all diving or other unauthorised forms of exploration are prohibited under the Protection of Military Remains Act 1986.[134] In clear water conditions, the upturned hull can be seen reaching to within 5 m of the surface. The brass letters that formed Royal Oak's name were removed as a keepsake by a recreational diver in the 1970s. They were returned almost twenty years later, and are now displayed in the Scapa Flow visitor centre in Lyness.[135] Royal Oak's loss is commemorated in an annual ceremony in which Royal Navy divers place the White Ensign underwater at her stern.[136]

A memorial at St Magnus Cathedral in nearby Kirkwall displays a plaque dedicated to those who died, beneath which a book of remembrance lists their names. This list of names was not released by the Government until 40 years after the sinking. Each week a page of the book is turned. The ship's bell was recovered in the 1970s and, after being restored, was added to the memorial in St Magnus.[137] Twenty-six bodies, eight of which could not be identified,[138] were interred at the naval cemetery in nearby Lyness.[139]

Environmental concerns

Royal Oak sank fully fuelled with approximately 3,000 tons of furnace fuel oil aboard.[140] The oil leaked from the corroding hull at an increased rate during the 1990s and concerns about the environmental impact led the Ministry of Defence to consider plans for extracting it.[141] Royal Oak's status as a war grave required that surveys and any proposed techniques for removing the oil be handled sensitively: plans in the 1950s to raise and salvage the wreck had been dropped in response to public opposition.[142] In addition to the ethical concerns, poorly managed efforts could destabilise the wreck, resulting in a mass release of the remaining oil;[143] the ship's magazines also containing many tons of unexploded ordnance.[144][lower-alpha 13]

The MOD commissioned a series of multi-beam sonar surveys to image the wreck and appraise its condition.[145] The high-resolution sonograms showed Royal Oak to be lying almost upside down with her top works forced into the seabed. The tip of the bow had been blown off by U-47's first torpedo and a gaping hole on the starboard flank was the result of the triple strike from her second successful salvo.[144][146] Following several years of delays, Briggs Marine was contracted by the MoD to conduct the task of pumping off the remaining oil.[147] Royal Oak's mid-construction conversion to fuel oil had placed her fuel tanks in unconventional positions, complicating operations. By 2006, all double bottom tanks had been cleared and the task of removing oil from the inner wing tanks with cold cutting equipment began the next year.[144] By 2010, 1,600 tons of fuel oil had been removed, and the wreck was declared to be no longer actively releasing oil into Scapa Flow.[147] Up to 783 m3 of oil is thought to remain within the ship; plans exist to resume pumping in mid-2021.[140]

2019 survey

Rebreather diver Emily Turton announced at the EUROTEK advanced diving conference in December 2018 that an international team of experts were surveying the wreck of Royal Oak to create a three-dimensional image of the war grave. This process takes thousands of man-hour dives over several months. The team used an extensive range of technology including videography, underwater photography and 3D photogrammetry to record the wreck. The survey had the full backing of the Royal Navy and the Royal Oak Association.[148]

See also

- List by death toll of ships sunk by submarines

- USS Arizona – another battleship sunk in harbour by a surprise attack and now a war grave

- Drake's Drum— mysterious victory drumming that erupted aboard Royal Oak when the German Imperial Navy surrendered at Scapa Flow in 1918 was attributed to the ghost of Sir Francis Drake

Notes

- ↑ "Cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight, 20 cwt referring to the weight of the gun.

- ↑ The irascible Collard infamously called Marine Bandmaster Percy Barnacle "a bugger" in the presence of guests, and that he had "never heard such a bloody noise".[39]

- ↑ Dönitz said of Prien: "He, in my opinion, possessed all the personal qualities and the professional ability required. I handed over to him the whole file on the subject and left him free to accept the task or not, as he saw fit."[76]

- ↑ The taxi driver's name was Robbie Tullock. He did not notice U-47 passing through his headlights.[80]

- ↑ "We are in Scapa Flow!"

- ↑ Cdr R.F. Nichols, Royal Oak's second-in-command, had narrowly escaped death 22 years earlier as a midshipman of Vanguard when he had been away from the ship the night she exploded.[84] He had been attending a concert-party on board the amenities ship Gourko, given by coincidence by sailors of Royal Oak, and had overstayed only because the show had overrun.[85]

- ↑ Cordite, used for propelling the shells, was prone to explode if allowed to overheat. The Court of Enquiry convened to investigate the loss of Vanguard concluded that the explosion of a cordite charge, either unstable or carelessly placed, was a likely cause of the disaster.[86]

- ↑ The portholes were not, in fact, fully open, but were covered with light excluders, designed to provide ventilation while maintaining blackout. Crucially, they were not watertight.[91]

- ↑ The official death toll for Royal Oak has varied over the years owing to confusion over similar names, lost records, and delayed deaths. The currently accepted figure of 835 deaths was determined in 2019 after research by a team of local historians.[93]

- ↑ Its wreck was not discovered until 2017.[97]

- ↑ "My Path to Scapa Flow"

- ↑ One U-47 crew member, Herbert Hermann, later took British citizenship.[129]

- ↑ By 2019, the ship was thought to contain 248 tons of TNT equivalent of unexploded ordnance.[140]

Footnotes

- ↑ Warlow & Bush, p. 1.

- ↑ Gardiner 1965, p. 87.

- ↑ Burt 1986, pp. 81, 271–272

- ↑ Burt 1986, pp. 276, 281

- ↑ Burt 2012, p. 156

- ↑ Burt 1986, pp. 276, 282

- ↑ Burt 1986, pp. 274–276

- ↑ Raven & Roberts 1976, p. 33

- ↑ Burt 1986, p. 276

- ↑ Burt 1986, pp. 272–273, 276

- ↑ Raven & Roberts 1976, p. 36

- ↑ Burt 1986, p. 277

- 1 2 Raven & Roberts 1976, p. 44

- ↑ Raven & Roberts 1976, pp. 44, 172–173

- 1 2 3 Burt 1986, p. 282

- 1 2 Campbell 1980, p. 23

- 1 2 3 Burt 2012, p. 163

- ↑ Burt 1986, p. 284

- ↑ Raven & Roberts 1976, pp. 172–173

- ↑ Burt 1986, p. 285

- ↑ Burt 1986, pp. 276–277

- ↑ Colledge & Warlow 2006, pp. 300–301

- ↑ Battle of Jutland: Order of Battle, Schlielauf, Bill, archived from the original on 14 December 2006, retrieved 22 February 2007

- ↑ Tarrant 1995, pp. 62–64

- ↑ Campbell 1998, p. 37

- ↑ Campbell 1998, p. 146

- ↑ Campbell 1998, pp. 152–157

- ↑ Campbell 1998, p. 210

- ↑ Campbell 1998, pp. 207–208

- ↑ Campbell 1998, pp. 211–212

- ↑ Campbell 1998, pp. 256, 274

- ↑ Campbell 1998, pp. 309–310

- ↑ Campbell 1998, pp. 346, 358

- ↑ Massie 2003, pp. 682–684

- ↑ Halpern 1995, pp. 418–420

- ↑ Admiralty (1918), ADM156/90: Board of Enquiry into sinking of HMS Campania, HMSO

- ↑ Herwig 1998, pp. 254–256

- ↑ "Admiral's Oaths", Time, 9 April 1928, archived from the original on 3 March 2009, retrieved 29 December 2006

- ↑ Glenton 1991, pp. 28–34

- ↑ "Trial by Oaths", Time, 16 April 1928, archived from the original on 30 September 2007, retrieved 29 December 2006

- ↑ Glenton 1991, pp. 177–183

- ↑ Gardiner 1965, pp. 132–134

- 1 2 "Royal Oak", Time, 26 March 1928, archived from the original on 3 March 2009, retrieved 29 December 2006

- ↑ Gardiner 1965, p. 176

- 1 2 "Questions for the First Lord of the Admiralty", Hansard Parliamentary Debates, 18 April 1928

- ↑ Glenton 1991, p. 162

- ↑ Gardiner 1965, p. 226

- ↑ "No. 33523". The London Gazette. 6 August 1929. p. 5145.

- ↑ Gardiner 1965, pp. 236–238

- ↑ "No. 33706". The London Gazette. 10 April 1931. p. 2332.

- ↑ Glenton 1991, p. 1

- ↑ "Erwin Schulhoff", exil-archiv (in German), Else Lasker-Schüler-Foundation, archived from the original on 18 October 2007, retrieved 3 September 2009

- 1 2 Admiralty, ADM53/105583: Ship's Log: HMS Royal Oak, February 1937, HMSO

- ↑ "Incident near Gibraltar", The Scotsman, 4 February 1937

- ↑ Bombing Attack on HMS Royal Oak, Attacks on HM Ships August 1936 – September 1937, HMSO, 1937

- ↑ "Shell falls on the Royal Oak", The Scotsman, 25 February 1937

- ↑ "Shell hurts five on ship", The Washington Post, 24 February 1937

- ↑ BBC, Britain's Basque Bastion, archived from the original on 30 October 2005, retrieved 1 February 2008

- ↑ Gretton 1984, pp. 379–381

- ↑ Film & TV Database, British Film Institute, archived from the original on 5 May 2009, retrieved 17 March 2009

- ↑ Mackenzie, S. P. (2001), British War Films, 1939–1945: The Cinema and the Services, Continuum International, p. 18, ISBN 1-85285-258-5

- ↑ "Late Queen Maud", The Scotsman, 24 November 1938

- 1 2 McKee 1959, p. 17

- ↑ Taylor 2008, p. 45

- 1 2 3 4 McKee 1959, pp. 23–24

- 1 2 Weaver 1980, pp. 29–30

- ↑ Sarkar 2010, p. 49

- ↑ Miller 2000, p. 15

- 1 2 3 4 5 Admiralty 1939

- ↑ Helgason, Guðmundur. "WWI U-boats: U 18". German and Austrian U-boats of World War I - Kaiserliche Marine - Uboat.net. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- 1 2 Miller 2000, p. 51

- ↑ Miller2000, pp. 24–25

- ↑ Helgason, Guðmundur. "WWI U-boats: UB 116". German and Austrian U-boats of World War I - Kaiserliche Marine - Uboat.net. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- ↑ Scapa Flow, firstworldwar.com, 22 December 2002, archived from the original on 16 February 2007, retrieved 24 December 2006

- ↑ "Lord's Admissions", Time, 20 November 1939, archived from the original on 8 March 2008, retrieved 22 December 2006

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dönitz 1959, pp. 67–69

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kriegsmarine 1939

- ↑ Snyder 1976, p. 86

- ↑ Prien 1969, p. 152

- 1 2 Weaver 1980, "Chapter 3: The Car on the Shore"

- ↑ Weaver 1980, p. 101

- ↑ Snyder 1976, p. 91

- 1 2 Snyder 1976, p. 95

- ↑ Vanguard's Casualties + Survivors, Great War Document Archive, archived from the original on 6 March 2017, retrieved 1 January 2008

- ↑ Snyder 1976, p. 101

- ↑ Smith 1989, pp. 84–85

- ↑ McKee 1959, p. 39

- ↑ McKee 1959, p. 42

- ↑ Weaver 1980, p. 118

- 1 2 Weaver 1980, pp. 60–61

- ↑ Snyder 1976, p. 115

- ↑ Snyder 1976, p. 121

- ↑ "Images reveal extent of HMS Royal Oak torpedo attack", BBC News, BBC News Scotland, 14 October 2019, retrieved 17 October 2019

- 1 2 Taylor 2008, pp. 96–97

- ↑ Weaver 1980, "Chapter 5: 'Daisy, Daisy"

- ↑ Snyder 1976, pp. 135–139

- 1 2 Stickland, Katy (12 October 2017). "Missing HMS Royal Oak steam pinnace discovered". Yachting and Boating World. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ↑ "Royal Navy's Loss", The Scotsman, 16 October 1939

- ↑ Admiralty, ADM53/110029: Ship's Log: HMS Pegasus, October 1939, HMSO

- ↑ "Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood", Supplement to London Gazette, 1 January 1940

- ↑ McKee1959, "Dedication"

- ↑ Weaver 1980, p. 58

- ↑ Weaver 1980, p. 56

- ↑ "U-Boat Warfare", Hansard Parliamentary Debates, 17 October 1939

- ↑ Weaver 1980, pp. 112–128

- ↑ "Boys (Active Service)", Hansard Parliamentary Debates, 25 October 1939, archived from the original on 5 July 2009, retrieved 14 October 2009

- ↑ Smith 1989, pp. 89–95

- ↑ "German claims", The Scotsman, 17 October 1939

- ↑ Two Broadcasts by Hans Fritzsche, archived from the original on 11 December 2006, retrieved 1 January 2007

- 1 2 3 Snyder 1976, pp. 179–180

- ↑ Williamson, Gordon & Bujeiro, Ramiro (2004). Knight's Cross and Oak-Leaves Recipients 1939–40. Osprey Publishing. pp. 20–23. ISBN 978-1-84176-641-6.

- ↑ Weaver 1980, pp. 133–134

- ↑ Weaver 1980, "Chapter 10: The Neger in the Woodpile"

- ↑ McKee 1959, "Chapter 13: Such Exaggerations and Inaccuracies ..."

- ↑ Weaver 1980, p. 77

- ↑ Weaver 1980, p. 120

- ↑ Weaver 1980, p. 123

- ↑ "The Churchill Barriers", Burray, archived from the original on 2 May 2006, retrieved 3 February 2007

- ↑ Weaver 1980, p. 104

- 1 2 3 Hayward 2003, pp. 30–31

- 1 2 McKee 1959, "Chapter 14: The Watchmaker who never was"

- ↑ Knobelspiesse, A. V. (1996), Masterman Revisited, Center for the Study of Intelligence, archived from the original on 13 June 2007, retrieved 9 February 2012

- ↑ Snyder 1976, p. 174

- ↑ Pforzheimer, Walter (1987), "Literature on Intelligence" (PDF), Proc. 31st Annual Military Librarians' Workshop, Defense Intelligence Agency: 23–37, archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2012, retrieved 10 June 2007

- ↑ Taylor 2008, p. 90

- ↑ Sarkar 2010, pp. 75–76

- ↑ Snyder 1976, p. 203

- ↑ Sarkar 2010, p. 130

- 1 2 Sarkar 2010, pp. 208–209

- ↑ Sarkar 2010, pp. 87–88

- ↑ Alison Shaw (23 June 2015). "Obituary: Kenneth Toop, survivor of HMS Royal Oak". The Scotsman. Retrieved 26 May 2021.

- ↑ Taylor, Craig (15 December 2016). "Only the memories are left". The Orcadian.

- ↑ Wrecks designated as Military Remains, Maritime and Coastguard Agency, archived from the original on 19 February 2012, retrieved 27 December 2006

- ↑ Sarkar 2010, p. 138

- ↑ Remembrance Day: Royal Oak's Royal Navy standard replaced by divers, BBC, 8 November 2013, retrieved 4 February 2020

- ↑ Memorial to HMS Royal Oak, St Magnus Cathedral, archived from the original on 2 February 2007, retrieved 27 December 2006

- ↑ "Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ↑ Smith 1989, p. 104

- 1 2 3 Hill, Polly (22 May 2019). Managing the Wreck of HMS Royal Oak (PDF). Spillcon 2019. Perth. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ↑ Arlidge, John (18 February 2001), "New battle engulfs Royal Oak", The Observer, archived from the original on 18 August 2016, retrieved 17 December 2016

- ↑ Snyder 1976, p. 210

- ↑ "HMS Royal Oak plans delayed by a year", The Orcadian, 23–29 April 2001, archived from the original on 15 December 2006

- 1 2 3 "Technology gives new view of HMS Royal Oak" (PDF), DLO News, Defence Logistics Organisation, August 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2012

- ↑ Rowland, C., Fishing With Sound: An Aesthetic Approach to Visualising Our Maritime Heritage (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2014, retrieved 9 April 2012

- ↑ Watson, Jeremy (24 September 2006), "Picture perfect: the fallen Oak", The Scotsman on Sunday

- 1 2 Royal Oak Oil Removal Programme, Briggs Marine, archived from the original on 3 January 2014, retrieved 27 January 2012

- ↑ "New images reveal sunken Royal Oak battleship". BBC. 1 February 2019. Archived from the original on 5 May 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

References

- Admiralty (1939), ADM199/158: Board of Enquiry into Sinking of HMS Royal Oak, HM Stationery Office

- Burt, R. A. (2012), British Battleships, 1919–1939 (2nd ed.), Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-59114-052-8

- Burt, R. A. (1986), British Battleships of World War One, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 0-87021-863-8

- Campbell, John (1998), Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting, London: Conway Maritime Press, ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1

- Campbell, N.J.M. (1980). "Great Britain". In Chesneau, Roger (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. New York: Mayflower Books. pp. 2–85. ISBN 0-8317-0303-2.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969], Ships of the RoyalNavy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.), London: Chatham Publishing, ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8

- Dönitz, Karl (1959), Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days, English translation by R.H. Stevens, Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-80764-5

- Gardiner, Leslie (1965). The Royal Oak Courts Martial. Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons. OCLC 794019632.

- Glenton, Robert (1991), The Royal Oak Affair: The Saga of Admiral Collard and Bandmaster Barnacle, Leo Cooper, ISBN 0-85052-266-8

- Gretton, Peter (1984), The Forgotten Factor: The Naval Aspects of the Spanish Civil War, Oxford University Press

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Hayward, James (2003), Myths and Legends of the Second World War, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509-3875-7

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980], "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918, Amherst: Humanity Books, ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9

- Kriegsmarine (1939), Log of the U-47, reproduced in Snyder and Weaver

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-45671-1.

- Miller, James (2000), Scapa: Britain's Famous War-time Naval Base, England: Birlinn, ISBN 1-84158-005-8

- McKee, Alexander (1959), Black Saturday: The Royal Oak Tragedy at Scapa Flow, England: Cerberus, ISBN 1-84145-045-6

- Prien, Günther (1969), Mein Weg nach Scapa Flow, Translated into English by Georges Vatine as I Sank the Royal Oak, Wingate-Baker, ISBN 0-09-305060-7

- Raven, Alan & Roberts, John (1976), British Battleships of World War Two: The Development and Technical History of the Royal Navy's Battleship and Battlecruisers from 1911 to 1946, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 0-87021-817-4

- Sarkar, Dilip (2010), Hearts of Oak: The Human Tragedy of HMS Royal Oak, Amberley, ISBN 978-1-84868-944-2

- Smith, Peter C. (1989), The Naval Wrecks of Scapa Flow, The Orkney Press, ISBN 0-907618-20-0

- Snyder, Gerald (1976), The Royal Oak Disaster, Presidio Press, ISBN 0-89141-063-5

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995), Jutland: The German Perspective, London: Cassell Military Paperbacks, ISBN 0-304-35848-7

- Taylor, David (2008), Last Dawn: The Royal Oak Tragedy at Scapa Flow, Argyll, ISBN 978-1-906134-13-6

- Warlow, B. & Bush, S. (2021). Pendant Numbers of the Royal Navy: A Complete History. Seaforth. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-5267-9378-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weaver, H. J. (1980), Nightmare at Scapa Flow: The Truth About the Sinking of HMS Royal Oak, England: Cressrelles, ISBN 0-85956-025-2

Further reading

- Kriegsmarine. "Report on Sinking of Royal Oak". uboatarchive.net. British Admiralty Naval Intelligence Division translation 24/T 16/45. Archived from the original on 3 January 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2006.

- Lenton, H. T. (1998). British & Empire Warships of the Second World War. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-048-7.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1966]. British Battleships, Warrior 1860 to Vanguard 1950: A History of Design, Construction, and Armament (New & rev. ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

External links

- hmsroyaloak.co.uk Website dedicated to the ship and its crew

- Royal Oak details and hydrographic report (in French, German and Dutch)

- Maritimequest photo gallery

- HMS Royal Oak at naval-history.net

- Helgason, Guðmundur. "The Bull of Scapa Flow". German U-boats of WWII – uboat.net.

- Animation of wreck

- Part transcript of ADM 199/158 Board of Enquiry in National Archives

- IWM interview with survivor Howard Instance

- IWM interview with survivor John Hall

- IWM interview with survivor Herbert Pocock

- Battle of Jutland Crew Lists Project: HMS Royal Oak crew list