| St Stephen Walbrook | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Location | 39 Walbrook, Walbrook, London EC4N 8BN |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | https://ststephenwalbrook.net/ |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed building |

| Architect(s) | Sir Christopher Wren |

| Style | Baroque |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | London |

St Stephen Walbrook is a church in the City of London, part of the Church of England's Diocese of London. The present domed building was erected to the designs of Sir Christopher Wren following the destruction of its medieval predecessor in the Great Fire of London in 1666. It is located in Walbrook, next to the Mansion House, and near to Bank and Monument Underground stations.

Early history

The original church of St Stephen stood on the west side of the street today known as Walbrook and on the east bank of the Walbrook,[1] once an important fresh water stream for the Romans running south-westerly across the City of London from the City Wall near Moorfields to the Thames. The original church is thought to have been built directly over the remains of a Roman Mithraic Temple following a common Christian practice of hallowing former heathen sites of worship.[2]

The church was moved to its present higher site on the other side of Walbrook Street, still on the east side of the River Walbrook[3] (later diverted and concealed in a brick culvert running under Walbrook Street and Dowgate Hill on a straightened route to the Thames),[4] in the 15th century. In 1429 Robert Chichele, acting as executor of the will of the former Lord Mayor, William Standon, had bought a piece of land close to the Stocks Market (on the site of the later Mansion House) and presented it to the parish.[3] Several foundation stones were laid at a ceremony on 11 May 1429,[5] and the church was consecrated ten years later, on 30 April 1439.[6] At 125 feet (38 m) long and 67 feet (20 m) wide, it was considerably larger than the present building.[7]

The church was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666.[3] It contained a memorial to the composer John Dunstaple. The wording of the epitaph had been recorded in the early 17th century, and was reinstated in the church in 1904, some 450 years after his death. The nearby church of St Benet Sherehog, also destroyed in the Great Fire, was not rebuilt; instead its parish was united with that of St Stephen.[3]

Wren's church

The present building was constructed between 1672 and 1679[8] to a design by Sir Christopher Wren, at a cost of £7,692.[7] The mason was Thomas Strong brother of Edward Strong the Elder and the spire is by Edward Strong the Younger.[9] It is rectangular in plan,[10] with a dome and an attached north west tower. Entry to the church is up a flight of sixteen steps, enclosed in a porch attached to the west front.[3] Wren also designed a porch for the north side of the church. This was never built, but there once was a north door, which was bricked up in 1685, as it let in the offensive smells from the slaughterhouses in the neighbouring Stocks Market.[11] The walls, tower,[12] and internal columns [3] are made of stone, but the dome is of timber[12] and plaster with an external covering of copper[13]

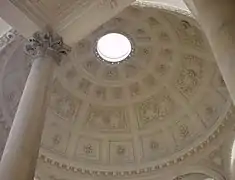

The 63 feet (19 m) high dome is based on Wren's original design for St Paul's, and is centred over a square of twelve columns[14] of the Corinthian order.[3] The circular base of the dome is not carried, in the conventional way, by pendentives formed above the arches of the square, but on a circle formed by eight arches that spring from eight of the twelve columns, cutting across each corner in the manner of the Byzantine squinch.[14] This all contributes to create what many consider to be one of Wren's finest church interiors. Sir Nikolaus Pevsner lists it as one of the ten most important buildings in England.

The contemporary carved furnishings of the church, including the altarpiece and Royal Arms, the pulpit and font cover, are attributed to the carpenters Thomas Creecher and Stephen Colledge, and the carvers William Newman and Jonathan Maine.[15]

In 1760 a new organ was provided by George England.

In 1776 the central window in the east wall was bricked up to allow for the installation of Devout Men Taking Away the Body of St Stephen, a painting by Benjamin West, which the rector, Thomas Wilson, had commissioned for the church.[16][17] The next year Wilson set up in the church a statue of Catharine Macaulay, (then still alive) whose political ideas he admired. It was removed after protests.[18] The east window was unblocked, and the picture moved to the north wall, during extensive restorations in 1850.[19]

Recent history

The church suffered slight damage from bombing during the London Blitz of 1941 and was later restored. In 1954, the united parishes of St Mary Bothaw and St Swithin London Stone (merged in 1670) were themselves united with the parish of St Stephen.

The church was designated a Grade I listed building on 4 January 1950.[13]

In 1953 the Samaritans charity was founded by the rector of St Stephen's, Dr Chad Varah. The first Samaritans branch (known as Central London Branch) operated from a crypt beneath the church before moving to Marshall Street in Soho. In tribute to this, a telephone is preserved in a glass box in the church. The Samaritans began with this telephone, and today the voluntary organisation staffs a 24-hour telephone hot-line for people in emotional need.

In 1987, as part of a major programme of repairs and reordering,[17] a massive white polished stone altar commissioned from the sculptor Henry Moore by churchwarden Peter Palumbo was installed in the centre of the church.[20] Its unusual positioning required the authorisation of a rare judgement of the Court of Ecclesiastical Causes Reserved.[21] In 1993 a circle of brightly coloured kneelers designed by Patrick Heron was added around the altar.[22]

Benjamin West's Devout men taking away the body of St Stephen, previously hung on the north interior wall, was put into storage following the reordering. This decision was controversial, as the initial removal of the painting was illegal.[23] In 2013 the church was given permission to sell the painting to a foundation, despite opposition from the London Diocesan Advisory Committee for the Care of Churches, and by the Church of England's Church Buildings Council.[23] Prior to the painting's export, a temporary export bar was placed on it to give it a last chance to stay in the UK.[24] The foundation has since loaned it to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which has undertaken restoration work on the painting.[17][25]

On 14 July 1994, the church was the venue for the wedding of Lady Sarah Armstrong-Jones to Daniel Chatto.[26]

At the time of his retirement in 2003, at the age of 92, Dr Chad Varah was the oldest serving incumbent in the Church of England.[27]

Rectors

- Peter 1301–1302 [28]

- Hugh de Marny 1315

- Willian de Stansfield 1325–1327

- Thomas Blundell 1350–1359

- Robert Eleker 1351–1385

- John Brown 1391–1395

- John Horewood 1395–1396

- Henry Chichele 1396–1397. Later Archbishop of Canterbury

- John Horewood 1397–1400

- John Beachfount 1400–1403

- Radman died 1419

- William Rock 1422. Resigned

- Thomas Southwell 1428–1440

- William Trokill 1440–1474

- Robert Rous 1474–1479

- William Sutton 1479–1502

- John Young 1502

- John Kite 1522–1534

- Elisha Bodley 1534

- Thomas Becon

- William Ventris 1554–1556

- Henry Pendleton 1556–1557

- Humphrey Busby 1557–1558

- Philip Pettit 1563 or 1564

- John Bendale 1563 or 1564

- Henry Wright 1564–1572

- Henry Trippe 1572–1601

- Roger Fenton 1601–1616

- Thomas Muriel 1615–1625

- Aaron Wilson 1625–1635

- Thomas Howell 1635–1641

- Michael Thomas 1641–1642

- Thomas Warren 1642

- Thomas Watson 1642–1662. Sequestered.

- Robert Marriott 1662–1689

- William Stonestreet 1689–1716

- Joseph Rawson 1716–1719

- Joseph Watson 1719–1737

- Thomas Wilson 1737–1784

- George S. Townely 1784–1835

- George Croly 1835–1861. Also a poet and novelist.

- William Windle 1861–1899

- Robert Stuart de Corcy Laffan 1899–1927[29]

- Charles Clark 1927–1940[30][31]

- Frank Gillingham 1940–1953[32]

- Chad Varah 1953–2003[33]

- Peter Delaney 2004–2014. As priest in charge[34]

- Jonathan Evens 2015–2018. As priest in charge

- Stephen Baxter 2018–

Burials

_School_-_Sir_Rowland_Hill_(1492%E2%80%931561)_-_1298284_-_National_Trust.jpg.webp)

- Sir Rowland Hill, of Soulton publisher of the Geneva Bible, styled "First Protestant Lord Mayor of London": his monument was lost in the Great Fire of London but was restated at Hawkstone

- John Dunstaple, musician

- Elizabeth Jekyll (1624-1653) diarist[35]

- John Vanbrugh, architect

The nearest London Underground station is Bank.

Gallery

Interior of St Stephen Walbrook

Interior of St Stephen Walbrook St Stephen Walbrook Ceiling 21st century

St Stephen Walbrook Ceiling 21st century The organ over the west door

The organ over the west door The wooden pulpit with its huge tester

The wooden pulpit with its huge tester The covered font

The covered font The dome and lantern seen from outside

The dome and lantern seen from outside

See also

Notes

- ↑ White 1900, p.285

- ↑ "Early History of St Stephen Walbrook". St Stephen Walbrook. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Godwin, George; John Britton (1839). "St Stephen's, Walbrook". The Churches of London: A History and Description of the Ecclesiastical Edifices of the Metropolis. London: C. Tilt. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ↑ White 1900, p.63

- ↑ "The City of London Churches: monuments of another age" Quantrill, E; Quantrill, M p90: London; Quartet; 1975

- ↑ White 1900, p.288

- 1 2 White 1900, p.296

- ↑ "The City Churches" Tabor, M. p102:London; The Swarthmore Press Ltd; 1917

- ↑ Dictionary of British Sculptors 1660–1859 by Rupert Gunnis

- ↑ Britton and Pugin 1825, p34

- ↑ Perks, Sydney (1922). The History of the Mansion House. Cambridge University Press. p. 119.

- 1 2 Britton and Pugin 1825, p37

- 1 2 Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1285320)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- 1 2 Betjeman, John (1967). The City of London Churches. Andover: Pitkin. ISBN 0-85372-112-2.

- ↑ S. Bradley and N. Pevsner, London: The City Churches (The Buildings of England), (Yale University Press, London and New Haven 2002), pp. 129–30.

- ↑ White 1900, p.386

- 1 2 3 "Anglican court says Benjamin West altarpiece can go to Boston". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ White 1900, p.387

- ↑ White 1900, p.299

- ↑ Tucker, T. (2006). The Visitors Guide to the City of London Churches. London: Friends of the City Churches. ISBN 0-9553945-0-3.

- ↑ Re St Stephen Walbrook [1987] 2 All ER 578

- ↑ "Patrick Heron – St Stephen Walbrook". ststephenwalbrook.net.

- 1 2 Grosvenor, Bendor. "Church of England to sell important Benjamin West?". Art history news. Retrieved 6 November 2015.

- ↑ "Taking the body of St Stephen overseas". GOV.UK.

- ↑ "Conservation in Action: Benjamin West". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ "Looking back at the nuptials of Princess Margaret's daughter, Lady Sarah Chatto, on her wedding anniversary". Tatler. London. 14 July 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ↑ "Obituaries – The Reverend Prebendary Chad Varah". The Telegraph. 9 November 2007. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ↑ Rectors to 1904 from White, J. G. (1904). History of the Ward of Walbrook in the City of London. London: Privately printed. p. 338.; others as indicated

- ↑ "Mr. De Courcy Laffan". The Times (London, England). 18 January 1927. p. 16.

- ↑ "Ecclesiastical News". The Times (London, England). 9 November 1927. p. 17.

- ↑ "Church Times: "Clerical Obituary", 26 January 1940, p 67". Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ↑ "Church Times: "Clerical Obituary", 10 April 1953, p 280". Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ↑ "Obituary". The Independent. 10 November 2007. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- ↑ "The Venerable Peter Delaney MBE;". Trust for London. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ↑ Clarke, Elizabeth R. (23 September 2004). "Jekyll, John and Elizabeth et al". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1 (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/67136. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

References

- Britton, John; Pugin, A. (1825). Illustrations of the Public Buildings of London: With Historical and Descriptive Accounts of each Edifice. Vol. 1. London.

- White, J.G. (1904). History of the Ward of Walbrook in the City of London. London: Privately printed.