| St Mary Magdalene's Church, Battlefield | |

|---|---|

St Mary Magdalene's Church, Battlefield, from the southeast | |

| 52°45′02″N 2°43′25″W / 52.7506944°N 2.7235849°W | |

| OS grid reference | SJ 512 172 |

| Location | Battlefield, Shropshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | Churches Conservation Trust |

| History | |

| Authorising papal bull | 30 October 1410, from John XXIII |

| Status | Chantry 1406, Collegiate church by 1410–1548 Parish church, c.1548–1982 |

| Founded | 28 October 1406 (grant of site authorised) |

| Founder(s) | Roger Ive Richard Hussey Henry IV |

| Dedication | Saint Mary Magdalene |

| Dedicated | In or before March 1409 |

| Events | c.1500: West tower completed. 1548: College and chantry dissolved. 1861–62: Major restoration. |

| Associated people | Richard Hussey granted site. Henry IV granted advowsons and tithes, re-founded church in 1410. Edward VI presided over dissolution of chantries and colleges. Lady Annabella Brinckman initiated Victorian restoration. |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Redundant |

| Heritage designation | Grade II* |

| Designated | 19 September 1972 |

| Architect(s) | Samuel Pountney Smith (restoration) |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Gothic, Gothic Revival |

| Groundbreaking | 1406 |

| Completed | 1862 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Limestone, tiles and slates on roofs |

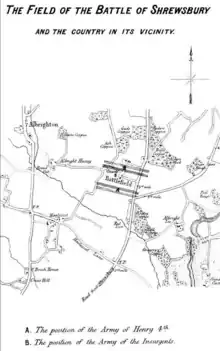

St Mary Magdalene's Church is in the village of Battlefield, Shropshire, England, dedicated to Jesus' companion Mary Magdalene. It was built on the site of the 1403 Battle of Shrewsbury between Henry IV and Henry "Hotspur" Percy, and was originally intended as a chantry, a place of intercession and commemoration for those killed in the fighting. It is probably built over a mass burial pit.[1] It was originally a collegiate church staffed by a small community of chaplains whose main duty was to perform a daily liturgy for the dead. Roger Ive, the local parish priest, is generally regarded as the founder, although the church received considerable support and endowment from Henry IV.

After the dissolution of the college and chantry in 1548, the building was used as the local parish church and it underwent serious decay, punctuated by attempts at rebuilding from the mid-18th century. A restoration in Victorian times was controversial in intention, scope and detail, although many original features remain. Today it is a redundant Anglican church. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II* listed building,[2] and is under the care of the Churches Conservation Trust.[3]

Foundation

The founders

In a grant of 27 May 1410 Henry IV portrayed himself as founder of the memorial chapel and chantry at Battlefield, granting land other endowments to Roger Ive, the Rector of Albright Hussey for this purpose.[4] Henry's version of events was long taken at face value, despite available evidence in his own letters patent that clearly contradicted it. In a 1792 contribution to The Gentleman's Magazine, David Parkes described Battlefield church as originally "a collegiate church of secular canons, built undoubtedly by order of the king."[5] Richard Brooke, writing about the field of battle in 1857, explained

In gratitude for, and in commemoration of, this victory, Henry the Fourth erected on the spot Battlefield Church; and from the circumstance of the battle having been fought on St Mary Magdalen's eve, he, in compliance with the prevalent opinions of the age, and probably also from his considering himself in some degree indebted to her for the victory, caused the church to be dedicated to St. Mary Magdalen.[6]

However, a Georgian historian of Shropshire, John Brickdale Blakeway, had long before disentangled the course of the foundation,[7] making clear that the initiative was local, coming from Roger Ive, the parish rector, and Richard Hussey, the lord of the manor. Blakeway's notes were not published until 1889, more than 60 years after his death, so W. G. D. Fletcher, an important Victorian antiquarian, was sometimes credited with discovering Roger Ive's claim to be the true founder.[8]

The true moment of foundation had already passed almost four years earlier than Henry IV's grant of 1410. On 28 October 1406 Henry had himself given a licence to Richard Hussey, the lord of the manor of Albright Hussey, to make a grant of two acres of land in Hateley Field to Roger Ive.[9] The land was to be held in frankalmoin, free of military and other secular services. Its initial purpose was specified as providing a site for a chantry chapel to sing masses for the souls of the king himself, his ancestors, and those killed in the battle. The foundation of the church was almost certainly on the suggestion of Roger Ive, with Hussey apparently entirely responsive and willing to donate the site.

Roger Ive is described as "of Leaton" and this is likely to be the village a short distance to the west of Albright Hussey (now Albrighton): there is another Leaton to the east of Shrewsbury. He was presented to the rectory of Albright Hussey by Richard Hussey on 22 October 1398.[10][11] On 8 January 1399 he was presented to the rectory of nearby Fitz, where Haughmond Abbey, a nearby Augustinian house, held the advowson.[12] Although a pluralist, Ive held two fairly poor benefices. Albright Hussey had once been divided between two important Shrewsbury churches, St Alkmund's and St Mary's, and there were still pensions and other outgoings to both St Mary's and Lilleshall Abbey, which had superseded the college of St Alkmund's.[13] Haughmond Abbey also took a cut at Fitz, where it had wrested control from St Mary's in 1256 after trial by combat.[14] In 1535, when Albright Hussey had been effectively absorbed into Battlefield chapel, it brought in only 20 shillings per year. Ive was clearly a strong and forceful personality who dominated developments at Battlefield until his retirement in 1447.[15]

Richard Hussey was a member of the Shropshire landed gentry, a middling landowner, although not a nobleman. The extent and limits of his wealth were displayed in January 1415 when he granted

"to Roger Yve clerk, Richard Colfex clerk, and William Sumpnour clerk, all my lands and tenements, rents and services, with their appurtenances, which I have in the towns of Adbryghton Husee, Harlascote, Salop, and Monkeforyate, within the county of Salop, together with the advowsons of the chapel of Adbrighton husee and of the chantry of blessed Mary Magdalene of the Batelfeld, and of Penkeriche within the county of Stafford: To have and to hold all the lands and tenements aforesaid, rents and services, with their appurtenances, together with the Advowsons aforesaid, to the aforesaid Roger, Richard and William, of the chief lords of those fees, their heirs and assigns, by the services thence due and of right accustomed, for ever."[16]

Fletcher, who gives the text of the document, points out that it was not intended to donate this property to the chaplains of Battlefield chapel, who never owned it. Rather it was part of a fresh settlement of the property. A grant to feoffees could both aid in tax avoidance and give the donor considerably greater freedom in disposing of his property. There is some ambiguity about whether the document was issued at Albright Hussey or Penkridge (Penkeriche) in neighbouring Staffordshire. During the late 12th century the Hussey family had held a large estate at Penkridge and were apparently recognised as lords of the manor.[17] A minority and the resulting wardship allowed King John to exert pressure on Hugh Hose or Hussey to transfer the estate and the important Collegiate Church of St Michael and All Angels to Henry de Loundres, recently consecrated Archbishop of Dublin in 1215.[18] Thereafter the Archbishops always held the deanery of the church, which belonged to the Crown,[19] despite Hussey's claim to the advowson. However, this assertion of a shadowy "intermediate lordship" in Penkridge seems to have been a family strategy for about three centuries.[20] Richard Hussey was presumably asserting the prestige of a family that had once been considerably more notable.

Henry IV's contribution

.jpg.webp)

Although the 1406 grant asserts that Hateley Field was the scene of the battle between and the king and Henry Percy, Philip Morgan, in a 600th-anniversary lecture, reminds us that "the battle had been fought across the open fields of three adjacent townships which also lay within at least two parishes of the nearby town."[21] The Victoria County History volume describes what followed the foundation as a series of "negotiations, 1406-10, between Ive, Hussey, and the Crown."[22] Morgan, in his classification of medieval memorial chapels, assigns Battlefield to those founded by "private speculators."[23] The negotiations seem to have drawn the king into a closer partnership. On 17 March 1409, in his capacity as Duke of Lancaster, Henry IV incorporated the chapel as a perpetual chantry, dedicated to Mary Magdalene, with eight chaplains, one of whom was to be Master. He also signalled his intention to grant it the advowson of St Michael's Church, St Michael's on Wyre, Lancashire.[24][25] This promise was implemented by letters patent under the seal of the Duchy of Lancaster on 28 May 1409.[26] The chapel was allowed not only to present the priest but to appropriate the tithes of Michaellskirke. The king had implied that the chapel was already built but this cannot have been entirely true, as he ordered the lead for the roof from the duchy's receiver at Tutbury Castle only in August of that year.[27]

Royal re-foundation

In the following year, the status and constitution of the chapel were changed. Ive had surrendered the land to the king, probably late in 1409, as Fletcher writes, "for some reason that does not appear."[28] Morgan points out that kings had an obvious motive to "assimilate a monument which might act as a focus for opposition to an official programme of memorialisation."[29] It suited Ive, Hussey and the king alike that the new foundation should appear to be a royal initiative. Blakeway, comments:

Upon the face of this' transaction, it rather looks as if Henry at first wished to give it the air of a tribute of loyal affection to his person and title from one of his zealous subjects; and considering the way in which he came by the crown, it was not unimportant for him to give it this appearance. At least I cannot otherwise account for this needlessly circuitous mode of conveyance. Why he found it afterwards expedient to proceed in a more direct course, and become himself the immediate founder, does not appear.[30]

On 7 February 1410, the king commissioned Sir William Walford to take possession of the site on his behalf.[31] The document gives a detailed description of the site and nearby property of the chapel and mysteriously describes it as having only six chaplains, together with Roger Ive as Master or Warden. It also includes Richard Hussey and his wife Isolda among those whose souls were to benefit from the masses offered. On 27 May 1410 the chapel was re-founded by a royal charter.[32] This established a community of five chaplains and a master to pray daily for the souls of the king, Richard Hussey and his wife, and for those killed in the battle. Ives and his successors as rector were to hold this post. The advowsons of St Michael's chapel in Shrewsbury Castle and its dependent chapel, St Julian's Church in Shrewsbury, and of St Andrew's Church in Shifnal were added to the endowments and Battlefield chapel was allowed to appropriate the tithes of all of them.[4] It was also allowed to hold a fair on the patronal feast, 22 July, each year.[33] The warden was to be free of all taxes and impositions, even those agreed by the clergy.

Papal confirmation

Ives wrote to obtain papal confirmation of the foundation. This came from John XXIII, a nominee of the Council of Pisa during the Western Schism, and so later condemned as an antipope. John's bull of 30 October 1410 was the first document explicitly to describe the Battlefield church as a college of priests: "a certain college which was called a perpetual chantry."[34] The document rehearsed the history of the foundation, the property boundaries and the endowments, confirming all of the king's grants, with the exception of the fair.[35][34]

Dedication

The dedication of the college and chantry was to Mary Magdalene and this had been decided by the time of Henry IV's endowment of Battlefield chapel in March 1409,[24] if not earlier. The Battle of Shrewsbury took place on 21 July, the vigil or eve of St Mary Magdalene's Day, which falls on 22 July. The unknown and unrecovered bodies of the dead would have been buried mainly on the saint's day. The only extant seal of the college, found on a deed of 1530,[36] is marked SIGILLUM COMMUNE DOMINI ROGERI IVE PRIMI MAGISTRI ET SUCCESSORUM SUORUM COLLEGII BEATE MARIE MAGDALENE IUXTA SALOP, showing that the dedication persisted and was regularly attested. The festival of Mary Magdalene was celebrated annually and accompanied by the fair.

Collegiate life

Colleges of secular clergy were the dominant form for new religious foundation by the 15th century.[37] The closest example to Battlefield was the College of St Bartholomew's Church, Tong, founded under a licence granted to Isabel of Pembridge on 25 November 1410, and so almost contemporary,[38] although it was purely a family chantry[39] and mausoleum, without the wider historical reference of Battlefield. There were a number of powerful older collegiate churches in the region, including those at Shrewsbury, St Peter's at Wolverhampton and St Michael's at Penkridge. These differed in significant ways from Battlefield. Blakeway comments that "a prebend in the more wealthy collegiate churches was recognised in the Middle Ages, and even much later, as a source of income for a good man of business, a clerk in the royal chancery or exchequer, or a useful member of the Roman curia."[40] Unlike these absentee careerists, "the chantry priests formed a resident body with definite duties."

Life in common

The chaplains at Battlefield initially had quarters in a three-story building next to the south side of the chancel and there are still visible remains of this.[41] Roger Philips acquired two parcels of land close to the south gate of the church and built three chambers on each to replace the old building. As he approached death in 1478 he settled these on the chaplains, on condition that they celebrate his anniversary on the Saturday after St Martin's Day (11 November) and pay 8d. annual rent to the Hussey family.[42] It is possible that a room in the church tower, which had a fireplace, also served as quarters for a resident priest.[43][44]

The duties and routines of the chaplains are covered in the will of Roger Ive,[45] This was made on 30 October 1444[46] and enrolled later in the Close Rolls.[47] In the will Ive mentions two deceased chaplains whose souls should be prayed for: William Howyk and Thomas Kyrkeby.[48] The executors of the will include three more chaplains: William Michell, Richard Jewet and John Ive,[49] a total of five, and possibly the original chaplains.[37]

Ive confirms that the chaplains then lived in a single manse, which had a shared buttery and kitchen. They had a single large dining table with two benches and a substantial batterie de cuisine, as well as 20 pewter vessels. These and all the other furnishings and fittings Ive bequeathed to them: up to this point they had been his own personal possessions.[50] The two daily meals, dinner and supper, were to be eaten together, with the Master, in the common dining hall: not privately or away from the premises. The annual boarding charge was to be four marks. They were under a general duty of obedience, sworn to the master on admission. Not only were they to eat together, but they must not leave the college without the master or warden's permission, on pain of a 3s. 4d. fine.[51] The penalty for keeping a wife or concubine was to be permanent expulsion from the college and forfeiture of any outstanding salary.[52] They had been accustomed to receive a salary of eight marks each from the proceeds of St Michael's on Wyre but Ive decreed that they should receive a pay rise of two marks, on condition that they recite a special collect for his soul on his anniversary, together with a Placebo or Vespers of the dead[53] and a Dirige or Matins of the dead, and a Requiem on the following day, in addition to the regular masses for the kings, the Hussey family and the battle-dead.[54]

Divine office

The tasks of the chaplains revolved around the Liturgy of the Hours, supplemented by liturgies specifically concerned with commemoration and the Sacrifice of the Mass specifically for the dead. These all followed the Use of Sarum, the dominant liturgical pattern in England at that period. There were a to be a Placebo and a Dirige each day, with the suffrages or memorial Preces, for souls of the departed: Henry IV and Henry V, described as founders; Richard Hussey, the first patron, and his wife Isolda; their descendants John Hussey, a further, deceased Richard Hussey, the surviving Richard Hussey and Thomas Hussey; Roger Ive, the first Master and the deceased chaplains, Howyk and Kyrkeby; and the those killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury. There were also two masses daily. The chaplains were bequeathed income from Ford Chapel on condition they undertake additional weekly observances, preferably on Monday:[48] this he reckoned would be enough to give them an extra four pence per week.[55] In most cases they were required to sit in facing rows in the choir, not in a single group.

The goods considered necessary for the divine office were listed carefully by Ive at the beginning of his will.[56] The equipment included three silver-gilt chalices; a silver-gilt pax board or osculatory, which was used for passing on the kiss of peace during Mass;[49] two silver cruets; three brass bells, which hung in the belfry. There was a substantial collection of books: two portiphories or ledgers, large books, which were breviaries of the Sarum rite; three gilt crosses; two new missals; two new graduals, containing the sung part of the Mass; three old missals, including one covered in red leather; an old portiphory; a processional; an executor of the office, probably a book of rubrics; a collectarium; four books of the Placebo and Dirige; a psalter, Then come the vestments: a complete suit in red velvet; a red velvet cope with two dalmatics; a suit made of white silk; a white silk cope with two dalmatics; four further suits. Finally is mentioned a yearly Manual, the handbook for administering the sacraments.[53]

Other activities

During a boundary dispute in 1581, a 63-year old witness, John Clarke, recalled "beinge a boy & goeing to schoole to the colledge of Battelfild, about 55 years past or thereabouts."[57] Fletcher considered that this was evidence that the college provided education locally.[58] Morgan points out the library of Trinity College, Cambridge has "a school book of a particular sort" that once belonged to Battlefield College. This is a parchment volume of 294 folios, bound with oak boards covered in white skin, and covering a range of subjects.[59]

In his will Roger Ive directed that any surplus remaining from alms and oblations collected for construction of the belfry should go to the poor and their almshouse.[51] In addition, this "hospital" was to receive any funds remaining if the chaplains failed to merit their pay rise of two marks.[55] This makes clear that such a hospital of almshouse was at least intended.

However, no expenditure by the college on either education or a hospital was recorded in the Valor Ecclesiasticus of 1535 or subsequently.[60] If they existed, they must have disappeared well before the closure of the college.

Observance and distraction

The chaplains were secular clergy, without a monastic rule, living in close proximity to lay people and subject to all the pressures of community and political life. Roger Ive considered the pressures so great that he obtained from Henry VI an exclusive right for the college to execute a wide range of writs and other legal instruments within its own site and the nearby estates.[61] The background was a period of political crisis, as well as great fiscal pressure for the government, as Suffolk, York and Henry VI himself competed for the power left vacant by the overthrow of the king's uncle, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, and the English cause in the Hundred Years' War was brought to the edge of disaster.[62] Even John Gillingham, whose revisionist account stresses the essential stability and continuity of 15th century government,[63] paints a picture of mismanagement, policy confusion, and an increasingly angry population during the 1440s.[64] According to the king's grant, the chaplains had complained that they were constantly harassed by all kinds of royal and local officials: bailiffs, Justices of the peace, Justices of assize, Seneschals and Marshals of the royal household, Sheriffs, Escheators, Coroners. They had been subject to undue fines, redemptions, amercements and distraints. This treatment was both pauperising the chaplains and reducing the value of their estates. It was necessary to give them peace and quiet so that they might attend seriously to their liturgical duties and so their servants and tenants might work conscientiously for them.[65] The solution was the reserve to the Master and chaplains the execution of all briefs, precepts, warrants, bills and mandates throughout the immediate territory of the chapel, the whole of the manor of Adbrighton Hussey and the township of Harlescott.[66] Hence, all of the royal and local officials who had been troubling the priests were forbidden to enter these areas in execution of writs of any kind.

Blakeway pointed out that the maximum income a chaplain might receive under Ive's will, including all supplements, was £7 5s. 4d. This would leave only £4 12s. after deducting the charge for board and lodging: not much for "the unremitted services of a man of education for every day of the year, and almost every hour of the day and night."[67] In fact the pay rise decreed by Ive seems not to have been granted, as the remaining chaplains were still receiving only 8 marks annually in 1548 on the eve of dissolution.[68] A small increment in kind might have come from the use of a garden and fish pond, which chaplains were certainly allowed in the later years of the college.[69] However, "whatever we may think of the utility of their employment, the members of this establishment did not eat the bread of idleness."[67]

Pluralism was a possible source of distraction and inattention to the business of the college. Adam Grafton exemplified pluralism, holding a wide range of posts that overlapped with his mastership of the college (1478 – c. 1518).[71] He was Vicar of St Alkmund's Church, Shrewsbury; Rector of St Dionis Backchurch, London; Rector of Upton Magna and Withington, Shropshire; Prebendary at St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury; Prebendary of Wellington in Lichfield Cathedral;[72] Dean of St Mary's College, Shrewsbury;[73] Archdeacon of Salop;[74] Archdeacon of Stafford.[75] It is likely he was seldom, if ever, resident at Battlefield: he perhaps lived at Withington, as it was there that he met with the Abbot of Haugmond and the Bailiffs of Shrewsbury for discussions in 1506.[76] The local bishop was the ordinary charged with instituting canonical visitations to investigate the chapel's discipline. A visitation in 1518 found the Master and chaplains struggling financially, partly owing to the burden of paying a pension to the recently retired Adam Grafton. However, they were generally observing the statutes well.[77] However it was not so in 1524.

Endowments and income

Roger Ive seems to have been largely content with the endowments secured by the college in 1410 and only small further acquisitions were made.[15] The assets of the college were concentrated in a tract of Shropshire, within a short distance of Watling Street, and well within the Diocese of Lichfield and Coventry. The one exception was St Michael's Church at St Michael's on Wyre, just to the east of Blackpool. This fell within the powerful and wealthy Archdiaconate of Richmond, which was able to act in most respects as a diocese in its own right, although actually part of the Diocese of York.[78]

Lands and rights

The lands and other known assets of Battlefield College are listed below.

| Location | Donor or original owner | Acquisition date | Nature of property | Approximate coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battlefield | Richard Hussey | 1406,[9] confirmed by King's re-donation, 1410.[4] | Battlefield church site and surrounding land | 52°45′03″N 2°43′25″W / 52.7507°N 2.7237°W |

| St Michael's Church, St Michael's on Wyre | Henry IV as Duke of Lancaster: "which advowson is parcel of our heritage of Lancaster."[79] | 1409 | Advowson, tithes and other dues | 53°51′46″N 2°49′10″W / 53.8628°N 2.8195°W |

| St Andrew's Church, Idsall[80] (now Shifnal) | Henry IV | 1410 | Advowson, tithes and other dues | 52°39′53″N 2°22′33″W / 52.6646°N 2.3758°W |

| Dawley Church (now Holy Trinity) | Henry IV | 1410 | Tithes and other dues. Dawley was included in the grant of Idsall church, as it was a dependent chapel.[81] | 52°39′18″N 2°27′48″W / 52.6550°N 2.4634°W |

| St Michael's Chapel, Shrewsbury Castle | Henry IV, a royal grant as St Michael's was a royal free chapel.[82] | 1410 | Advowson, tithes and other dues. | 52°42′27″N 2°44′59″W / 52.7076°N 2.7498°W |

| St Julian's Church, Shrewsbury | Henry IV, a royal grant as St Julian's was a royal free chapel.[83] and a dependency of St Michael's.[80] | 1410 | Tithes and other dues. | 52°42′25″N 2°45′08″W / 52.707°N 2.7521°W |

| Ford chapel (St Michael's Church) | Henry IV, a royal grant as Ford chapel was a dependency of St Michael's Chapel at Shrewsbury Castle, although not mentioned in the charter of 1410.[84] | 1410 | Tithes and other dues. | 52°43′09″N 2°52′18″W / 52.7191°N 2.8716°W |

| Harlescott | Purchased. Leased from Shrewsbury Abbey. | 1421 and 1428 | Small areas of land | 52°44′12″N 2°43′29″W / 52.7367°N 2.7246°W |

| Albright Hussey | Leased from Shrewsbury Abbey for 99 years, along with lands in Harlescott.[85] | 1421 and 1428 | Small areas of land | 52°44′12″N 2°43′29″W / 52.7367°N 2.7246°W |

| Aston, Shifnal,[86][47] called in 1534 Aston juxta Shuffnall[87] | Purchased. | Before 1444 | Township and grange | 52°40′10″N 2°21′18″W / 52.6694°N 2.3550°W, |

These properties did not necessarily come to Battlefield chapel immediately. St Michael's Chapel at Shrewsbury Castle was resigned by John Repynton, its warden, together with St Julian's, only in 1416[88] or 1417.[89] It seems that Ive was not always quick to find clergy for the appropriated chapels and churches. In the 1440s, the delay at Ford Chapel, which lay within a manor belonging to Lady Elizabeth Audley, widow of John Tuchet, 4th Baron Audley, was so prolonged that she enlisted the help of her brother, John Stafford, the Bishop of Bath and Wells and Lord Chancellor. Stafford wrote to William Heyworth, who was Bishop of Lichfield, although addressing him as Bishop of Chester, demanding rapid action to rectify the situation.[90]

Legal moves

The Masters of Battlefield were willing to defend their endowments and income at law when necessary. A record of the Court of Common Pleas, dated 1418, indicates that Roger Ive was expected to pay an annual rent to the Archdeacon of Richmond, Stephen Scrope,[91] a son of the late Richard le Scrope, Archbishop of York.[92] The record contains the response of Roger Ive or Yve, and thus is an extended rebuttal of the Archdeacon's claim.

Such actions were often collusive, intended to set a right enjoyed through custom and practice in writing. In his last years as Master, Ive fought an action in the Exchequer of Pleas, thought to be collusive,[93] to vindicated the college's exemption from taxation.[94] In 1461, early in his wardenship, Roger Philips demanded the tithes of Derfald, the deer park attached to Shrewsbury Castle, basing his claim on the college's rectorship of St Michael's Chapel at the castle. A dispute ensued with Haughmond Abbey, which had a grange there. This issue was finally resolved with the help of a mediator. Haughmond agreed to pay four shillings annually for the tithes and five for additional land nearby.[95]

Fundraising efforts

The fair was a useful source of income, coupled with the attraction of the Battlefield Church as a centre of pilgrimage. Both needed an added stimulus to bring in substantial profits, and this was achieved by soliciting the grant of indulgences for those who attended.[59] An indulgence of forty days' purgatory "for all supporters of the college or chantry of Mary Magdalene"[96] was granted on 17 April 1418 by Edmund Lacey, the Bishop of Hereford: well-timed to bring pilgrims to the fair, three months later. In 1423 Pope Martin V granted the much greater indulgence of five years and five quarantines (forty-day periods) to all who visited the Battlefield chapel on Passion Sunday or the following two days and made a donation to its construction and upkeep.[97] In 1443 Pope Eugenius IV extended the term of the indulgence again to seven years and seven quarantines, explicitly in response to a request from Henry VI. On this occasion, the pilgrim could attend on any of the major festivals or on St Mary Magdalene's Day.[98] In 1460 John Hales, then Bishop of Lichfield, granted a forty-day indulgence to all who made "pleasing gifts" to the college for construction or maintenance work.[99]

It seems that the bishop's indulgence did not bring in the required funds.[100] The following year brought in a new Yorkist régime that proved responsive to the needs of the college. Edward IV noted that the chantry was for his own "safe condition" (presumably as it was for the successors of Henry IV) and permitted the third master, Roger Philips, to send out his proctor, Thomas Brown, on a fund-raising mission across Staffordshire, Derbyshire and Warwickshire.[101] Morgan8 suggests that the church had become by this time a focus of resistance for Yorkists seeking to rally against the Lancastrian dynasty: this is evidenced by the presence of the arms of William FitzAlan, 16th Earl of Arundel,[102] who notably switched sides, joining Edward at Pontefract in 1460.[103] The king took Brown and his retinue under his own protection and ordered royal and local officials to ensure their safety and expedite restitution of any losses they might suffer. The use of proctors to collect funds evidently continued. On 10 March 1480 Thomas Mylling commended such a mission to his clergy.[104] On 14 July 1484 Myllyng issued a licence for Battlefield College to use its proctors collect alms throughout his diocese until Christmas.[105] As late as 11 October 1525 Henry VIII granted a brief to allow three of the college's proctor's to collect alms.[76][106]

Valor Ecclesiasticus

Under the Tudor dynasty the college's exemption from taxation was lost. A receipt, dated 1519, is extant for tax payments made by the college in respect of Ford chapel.[107] There is also a slightly threatening note demanding payment of taxes in person at the George Hotel, near Shrewsbury, on 18 January 1544. The burden of taxation was one of the complaints of the college, alongside that of pension payments to a retired Master, Adam Grafton, at the visitation of 1518.[77] However, in 1530 the college leased half its land at Aston, together with two houses and some of the tithes, to the Forster family for just 30 shillings a year and on a 94-year lease.[107]

At the Valor Ecclesiasticus in 1535 the whole of Aston brought in only 60 shillings, the only item to appear under the heading of Temporalities.[108] The college's gross income was given as £56 and sixteen pence, or £56 1s. 4d. By far the largest single contribution was a payment of £31 16s. from the lessee of the rectory of St Michael's on the Wyre. The rectory at Idsall or Shifnal was worth only £10. Small sums came from the tithes of the small chapels, including just 20 shillings from Albrighton itself, and £2 6s. 8d. from alms and oblations. The expenses were dominated by the salary of the Master, John Hussey, who drew £34 1s. 8d. The other five chaplains each received £4. The Valor Ecclesiasticus proved the death knell for small monasteries and nunneries, which were dissolved in the following year. However, its findings had no such consequences for Battlefield Church, which was not a monastery.

Masters or wardens

The following is a list of known masters or wardens of Battlefield College, based on that in the Victoria County History[109]

| Name | Instituted or first mentioned | Resigned or died | Key events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roger Ive or Yve | 1409>[25] | Resigned 1447,[110] on an annual pension of £10[111] | Ive has long been acknowledged as the true founder of Battlefield College.[8] In the later years of his mastership he seems to have been preoccupied with stabilising it as a durable institution that would outlast his personal involvement. In Michaelmas term of 1443 he commenced an action to vindicate the college's exemption from taxation.[112] His will of 1444 arranges the transfer of a wide range of his personal assets to the chaplains as a corporate group.[56] On 4 December 1445 he obtained from Henry VI for the college the exclusive right to execute writs in the vicinity of the college.[61] As there is no mention of his pension when Roger Phelips was instituted Master in 1454, he may have been dead by then.[113] | |

| Henry Bastard | 14 April 1447[114] | Died 1454 | Henry Bastard was a Master of Arts. Apparently he tried to exercise spiritual jurisdiction over the church of St Julian,[115] although the college held only the advowson and rectorship. | |

| Roger Phelips or Philips | 26 May 1454 | Died 1478 | At his institution, Phelips was forbidden to exercise spiritual jurisdiction over St Julian's or any other appropriated chapel by Bishop Reginald Boulers. He was required to take all of the college's documents relating to property grants to Beaudesert Palace by 1 June for inspection by the bishop personally. He was able to obtain from the succeeding bishop, John Hales, an indulgence for donors to the college[99] and from Edward IV permission to use proctors to raise funds.[101] It was Phelips who came to an agreement with Haughmond Abbey over the Shrerwsbury Castle deerpark.[95] | |

| Adam Grafton | Instituted 17 November 1478. | Resigned by 1518. Died 27 July 1530.[70] | A distinguished cleric, Grafton acted as chaplain to both Edward V and Arthur, Prince of Wales. He held numerous ecclesiastical posts alongside his mastership of Battlefield.[71] He was buried at Withington.[70] He was probably responsible for completing the tower of Battlefield Church and his name is carried on a shield in panelling on the east side of the tower: Ive had made construction of a replacement bell tower a priority use for alms,[51] but it was not completed until about the turn of the century.[116] | |

| John Hussey | Occurs 1518. | Last occurs 1521, died before 1524 | Little is known for certain of Hussey. He is known from a 61-year lease of land at Aston to the Hatton family, which he made in 1521.[117] | |

| Humphrey Thomas | Occurs from 1524 | Died 1534 | Thomas was able in 1525 to get permission from Henry VIII to send his proctors out fundraising because "the profits and revenues of the college named are not enough for the support of the master or warden and for the support of the other burdens falling daily upon the college."[76] In 1528 and 1530 he too granted very long leases of land at Aston.[118] | |

| John Hussey | Instituted 18 October 1534 | Surrendered at dissolution, 1548 | Hussey continued the policy of long leases, this time in Lancashire.[119] He was compelled to make returns on the value of the college's holdings under the Valor Ecclesiasticus.[120] he appointed a proctor to raise funds in London and Middlesex.[121] His last known act as master seems to have been his appointment of Edward Stevens to correct and reform crimes and to prove wills within the boundaries of St Julian's.[122][123] He retired on a pension of 20 marks.[124] | |

Dissolution

Abolition of chantries and colleges

The Dissolution of Colleges Act 1545 gave all colleges, free chapels and chantries to the king and commissioners were sent to inspect and report on them, issuing a certificate afterwards.[125] In 1546 the financial position of Battlefield was found to be broadly similar to that in Valor Ecclesiasticus.[126] However, the warden, John Hussey, had a salary of £20 19s. 5d., considerably less than a decade earlier, as it was calculated as the surplus remaining after the work of the college had been discharged – essentially the operating profit of the chantry.[127] The "five brethren" were still on salaries of 106s. 8d. or eight marks apiece. The certificate made clear that Battlefield was not, in fact, the parish church but was "wythin the paryshe of Adbryghton Hussie."

However, the college and most others were not actually dissolved at this point and a new Dissolution of Colleges Act 1547 was passed in 1547, the first year of the reign of Edward VI. A further inspection and certification followed, pending dissolution. Contrary to the previous inspection, this asserted that Battlefield was a parish church and it had 100 people in "necessitye of a Curate."[68] John Hussey's salary had contracted a little further, to £19 6s. and he was recorded as 40 years of age and in possession of another living. However, the certificate for St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury, where he held a prebend worth 7s. 2d. showed him as 36 years old and his other living, i.e. Battlefield, as paying only £13 6s. 8d.:[128] unexplained discrepancies. The other chaplains' incomes had not changed.[68] Only four were named: John Parson (aged 92), Roger Mosse (aged 50), John Buttrye (aged 40) and Edward Shord (aged 60). The college had devoted no money to preachers, schools or to the poor in that year.[129]

It appears that Battlefield College was closed early in 1548 and a pension of 20 marks was granted to Hussey in June.[124] The church became the parish church of Albright Hussey.[130] The second certificate had commented that Edward Shord "serveth the Cure."[68] After the dissolution, he was retained as curate of the parish church on a salary of £5.[131] When the collector or bailiff, John Cupper or Cowper, reported on his work, subsequently, he noted that Shord had been allocated a room called the Curate Chamber, worth 2s. 4d., for which no rent had been paid.[132]

Disposal of properties

While John Cupper handled the income stream from the properties of the former college, they were advertised for sale by the Court of Augmentations. The business was handled centrally for the Court by Sir Walter Mildmay, one of its surveyors,[133] and a client of Thomas Seymour, although a future Chancellor of the Exchequer of England.[134] The asking price was generally twenty times the annual value. Locally, the valuations and details of the Shropshire properties were signed off for the Court of Augmentations by Richard Cupper or Couper,[135] its surveyor in Shropshire and Staffordshire, who seems to have been John Cupper's brother,[136] and who was certainly a Shropshire man, although he too was now based in London. Richard Cupper was a client and close aide of William Paget, a key figure in the king's administration and an important Staffordshire landowner, although his family too were probably of humble origins in the West Midlands.[137]

John Cupper then appeared in his rôle as a large-scale speculator. In concert with Richard Trevor, both said to be London gentlemen, he bid for the Battlefield College properties.[138] However, the venture was much bigger than this. For a batch of properties, including numerous chantry estates, which were granted to them on 10 April 1549, they paid the Court of Augmentations the then large sum of £2050 13s 9d,[139] (equivalent to £1,047,654 in 2021) The former assets of Battlefield included in the deal were the church and rectory of St. Julian, Shrewsbury;[140] the site of the college (excluding the curate's lodging); Albright Hussey chapel; tithes of grain, corn, sheaves and hay in Harlescott, then in the tenure of Thomas Ireland; cottages called "lez bothes" on Hussey estate land near the college, which seem to have been market stalls; and the proceeds of the annual fair on St Mary Magdalene's day.[141][142] Thomas Ireland bought his tithes from John Cowper on 2 July that year.[143] It is probable Cowper and Trevor disposed of the remaining properties in a similar way, looking first to purchasers who already had an interest in the land and thus in maximising the profit of their own labours: certainly the former Hussey land was bought back at some stage in the process and remained in the family until 1638.

Small estates in Lancashire, around St Michael's on Wyre were marketed in a similar way and granted on 12 December 1549 to John Pykarell and John Barnard, who paid £243 18s 10d. (equivalent to £124,628 in 2021) for a batch that also included properties in Norfolk and Kent.[144] The particulars for the sale, drawn up by the Court of Augmentations, priced these former Battlefield properties at £26 8s., twenty-two times their annual value.[145] Thomas Sydney of Norfolk and Nicholas Halswell of Norfolk agreed to pay £40 for the township of Aston at Shifnal on 3 April 1553.[146] This was granted[147] on 1 May as part of a large batch for which they paid £1709 19s. 8½d. (equivalent to £772,354 in 2021), channelling the payment through Sir Edmund Peckham,[148] a prominent supporter of Princess Mary who was high treasurer of all the mints in England [149]

This fire sale at the end of a Protestant reign was followed by a long lull. Not until late in the reign of Elizabeth I did sales recommence, with the rectory of Shifnal put on the market in 1588 and Ford church two years later.[150] The patronage and rectory of St Michael's Church, St Michael's on Wyre, were retained by the Crown until the reign of James I.[151]

Decay and restoration

The college buildings were disused and were probably soon demolished. Their fabric would have been taken for other purposes. To the south of the church a surviving series of depressions has been thought to mark the site of the college fishponds or stews.[152][153] Falling population meant that the church continued to be used but its condition deteriorated. The roof was repaired in 1749, but later the nave roof completely collapsed.[1] In the late 18th century the nave was abandoned and the chancel was restored in neoclassical style, with four Doric columns forming a square.[154] The roofline of this modification was clearly visible from the south east or north east.[155] Philip Morgan gives credit for renewing interest in Battlefield Church and its history to two 18th century clerics: Leonard Hotchkiss and Edward Williams, who held the livings of both Battlefield and nearby Uffington and completed several watercolours. An illustrated contribution to the Gentleman's Magazine from David Parkes in 1792 also spread both information and misinformation, ascribing the foundation of the church to Henry IV and misrepresenting the pietà as a Madonna and child.[5] Drawings of the church from the mid-19th century show that it was not entirely roofless,[156] as the chancel remained in parochial use and the roof line was clearly visible from some viewpoints.

Richard Brooke visited the church in 1856, in preparation for his book on 15th century English battlefields and wrote:

The church is a handsome ecclesiastical edifice. The nave or body is now roofless and dilapidated; and, from its moss-grown and impaired appearance, must have been a ruin for a long period. It is said that the nave of the church suffered during the rule of the Parliament or of Cromwell. Its exterior walls, the mullions, and most of the tracery work (which is undoubtedly handsome) of its windows are, however, still existing. The nave is entered by a door in the original pointed arched doorway, on the north side; and its floor has long been used as a graveyard, or place of interment.[157]

Despite the decay, Brooke cautioned in a strongly-worded footnote against excessive zeal for restoration or improvement of the building.

When I visited the church in May 1856, 1 was very sorry to hear that a subscription had been entered into, for the purpose of what was termed "renovating" this curious and interesting edifice. As far as respects removing the modern pillars, and the plastered ceiling from the chancel, and making the latter appear more in accordance with its ancient state, few persons would object to that measure; but it ought to be borne in mind that the chancel will accommodate, and much more than accommodate, the whole number of church-goers of the very scanty population of Battlefield parish; and that the renovation or rebuilding of any other part is wholly unnecessary, with reference to the spiritual requirements of the parishioners. It would evince great want of taste and judgment to renovate or restore the ancient nave and tower. The remains are most valuable to the historian and archaeologist. The interval was so very short, comparatively speaking, between the erection of the church in the reign of Henry IV, and the seizure of the edifice and its contiguous college and hospital in the reign of Henry VIII, that we cannot doubt that the remains are now an authentic and interesting example of church architecture of the reign of the former monarch. The parties who wish for or recommend the renovation of the nave, or the restoration of the whole of Battlefield Church, may possibly find some architect, who, like an old-clothes man, may undertake to "renovate" the article which he is accustomed to deal in, or, in other words, to make it "as good as new"; but when the alterations in this church are finished, they may probably furnish an example of a lamentable destruction of a very ancient, curious, and historical relic of times gone by.[158]

In 1638 the ownership of the church site and the Albright Hussey estate had passed from the Hussey family to Pelham Corbet of Leigh.[159] It passed through the male line from Pelham Corbet until 1859, when a lifetime's interest was inherited by Lady Annabella Brinckman née Corbet, who was married to Sir Theodore Brinckman. She commissioned the architect Samuel Pountney Smith to restore the church and to build a mortuary chapel. This work was carried out between 1860 and 1862.

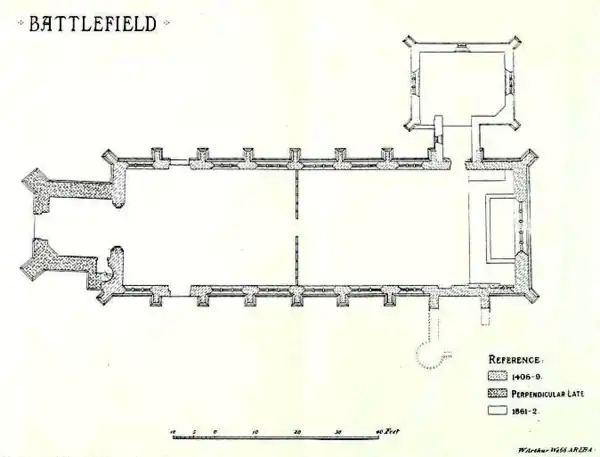

The Churches Conservation Trust is very positive about the restoration: "Much of the church we see today is the result of an extensive restoration in the 1860s, by a distinguished local architect S Pountney Smith, who saved the church from ruin." It mentions the features he created, including the "magnificent hammerbeam roof."[3] On the other hand, its guide for visitors, downloadable from the same webpage, minimises the impact of the restoration: "The fabric survives unaltered, very rare for a medieval church which would typically be built, rebuilt and added onto for hundreds of years." The clergyman and architectural lecturer David Cranage had some reservations, remarking in his 1903 article:

Turning now to the building itself, we must see how far the architectural detail fits in with the documentary evidence. We must first remember, however, that the church has undergone "restoration." Much of the prominent detail in the accompanying general views is modern, and dates from 1861–62, when the church was restored and added to under the direction of Mr. S. Pountney Smith. Mention should be made of the parapets and pinnacles, the hammer-beam roof, the screen and seats.[160]

Cranage included a plan of the restored church, but this is able to indicate clearly only the scope of the structural additions, while the impact came through these prominent details. Morgan identifies common features in all Pountney Smith's restorations, of which there were many. At three similar churches, including Battlefield, "he retained a medieval west tower whilst virtually rebuilding the remainder."[161] He is particularly critical of the hammerbeam roof, which was variously received but "fussy, handsome or magnificent, the problem is that it isn't medieval." There was a lack of real evidence on which to base a reconstruction.

In 1864 Lady Brinckman died and the Albright Hussey estate, including the church site, passed to the Pigott family, relatives who were required to change their name to Corbet.[151] After more than a century of further use as a parish church, the building was declared redundant in 1982 and became vested in the Churches Conservation Trust.[1] The tower and the nave underwent repairs in 1984.[162] It remains a memorial chapel to the battle-dead, with an annual service of commemoration.[163]

Architecture

Setting

The church is oriented very closely to the geographical east and stands in a churchyard, with the modern approach usually through a gate to the north. The old college precincts lay to the south but evidence of these is now very scanty.[164] On the south side of the chancel are slight remains of the foundations of the original college quarters,[41] but nothing of the building erected later by Phelips. Further away, to the south, are the footings of a former round tower. Some of the gravestones in the churchyard contain Victorian and Art Deco carving. At the north entrance to the churchyard is a lychgate which was built during the Victorian restoration but contains wood brought from Upton Magna church.[165]

Exterior

The church is built in limestone with roofs of tiles and Welsh slates.[2] Its plan consists of a simple rectangle, with a five-bay chancel and a four-bay nave of equal width. There is a west tower and a vestry (the former mortuary chapel) to the north-east. The tower is almost as wide as the nave, and is in two stages. It has diagonal buttresses and a square southeast stair turret. The name of Master Adam Grafton is inscribed on a shield high on the east side.[44] Also on the tower are the arms of Sir John Talbot, 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury.[1] In the lower stage is a west door above which is a two-light window. The upper stage has paired bell openings on each side. At the summit is a quatrefoil frieze, an embattled parapet, and pinnacles at the corners.[2] In the body of the church the bays are separated by full-height buttresses. The tracery in most of the windows is in Decorated style, inserted as part of the restoration, but some windows have retained their original tracery.[154] The east window is in Perpendicular style and has five lights. Above this window in a niche is a statue of Henry IV. The parapet of the nave is plain, and that of the chancel is an openwork quatrefoil.[2] Around the church are gargoyles representing mythical beasts and soldiers, almost all of them modern.[166] The vestry is battlemented and on its wall is the carved crest of the Corbet family (two crows).[1]

Interior

There is no structural division between the nave and the chancel. The dividing screen, which dominates the view on entering the building, was installed by Pountney Smith in the Victorian restoration.[165] The screen is controversial, as it would only have been strictly necessary if Battlefield had originally been a parish church, with the need to house the laity separately in a nave to the west of the chancel. It was not a parish church until after the Reformation. Cranage was even-handed on this feature, acknowledging the doubts but drawing attention to the much worse alternative of a brick wall used by the 18th century rebuilders: in general he approved.

The controversial hammerbeam roof by Pountney Smith is supported on the original stone corbels.[154] One of the corbels is carved with a Green Man.[1] The roof is decorated with carved shields acting as bosses, pendants, and traceried panelling.[2] The shields display the arms of knights who fought in the battle.[165] The church is paved with encaustic tiles made by Maw of Ironbridge.[2][154]

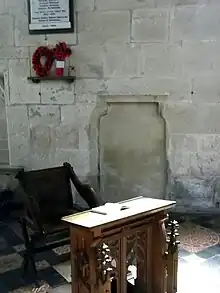

In the southeast part of the chancel is a triple sedilia, a set of three stone seats for the officiating priest and the assisting deacon and subdeacon. One sedile was for a time, both before and after the Victorian restoration, used to house the pietà.[166] There is also what remains of a piscina, or ceremonial wash basin: it has lost its projecting bowl but the niche is clear. There is a blocked doorway that formerly led to and from the chaplains' quarters, affording quick access to the chancel. On the wall of the chancel's south side is a marble tablet which is a war memorial to local men who died serving in the First and Second World Wars.[167] The doorway on the north of the chancel leads to the vestry, which is the former Corbet mortuary.[154] The reredos was designed by Pountney Smith, and contains high relief sculptures depicting the Nativity, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection. The font and the pulpit were also designed by Pountney Smith.[154] The pulpit is in stone with a white marble panel depicting Moses striking the rock to produce water. The top of the font is octagonal and is carved with angels. The ends of the wooden pews are carved with birds and animals.[1]

On the north side of the chancel is an oak pietà or Lady of Pity, dating probably from the middle of the 15th century. This is about 1.15m. In height and hollowed out behind.[166] It sometimes said to be from the church at Albright Hussey.[2][154] Previously there was also a belief that it was brought from Coventry.[168] However, there is no evidence for either suggestion and Thomas Auden challenged the need for a theory of removal as early as 1903, pointing out the existence of other oak carvings in Shropshire churches of the period. He considered the image particularly appropriate as "in a Church whose special object was the commemoration of the dead, it would be natural to place over one of the altars the figure of the Madonna represented in her hour of sorrow over her own dead Son. "Our Lady of Pity" would be to medieval ideas the very embodiment of all that is tender and sympathetic towards human sorrow, and so most appropriate in such a position." Although at first arguing for a date near the beginning of the 15th century, he later drew attention to a carving of the same subject on a bench end at St Laurence's Church, Ludlow, which can be dated with some confidence to 1447.[169] Victoria County History accepts this as a likely approximate date for the pietà.[170] Morgan thinks the statue was original to the college, especially in the light of other relatively high-status and expensive items, like the school book.[59]

In the vestry is stained glass from a number of sources, including original glass from the church, possibly dating from about 1434–45, and some early 16th-century French glass brought here from Normandy, as well as display material related to the battle. In the body of the church is glass by Lavers and Barraud dating from 1861 to 1863. The east window in the chancel contains a depiction of Mary Magdalene, and in the north and south windows are the twelve apostles. The west window of the tower depicts Christ and John the Baptist.[154] Also in the church is a wall memorial to the Corbet family under three ornate arches, hatchments, and Victorian gas fitments.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hollinshead, Liz (2002), Church of St Mary Magdalen, Battlefield: Information for Teachers, Churches Conservation Trust

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Historic England. "Church of St Mary Magdalene, Shrewsbury (1246192)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- 1 2 "Church of St Mary Magdalene, Battlefield, Shropshire". Churches Conservation Trust. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 Fletcher, pp. 187–9.

- 1 2 Gentleman's Magazine, volume 62, part 2, p. 893. Online copies of the note generally omit the illustration but it is available at Shropshire Archives: Battlefield church and Pieta.

- ↑ Brooke, p. 9.

- ↑ Blakeway, pp. 321–3.

- 1 2 Cranage, p. 171.

- 1 2 Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1405–1408, p. 263.

- ↑ Eyton, volume 10, p. 86.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 78.

- ↑ Eyton, volume 10, p. 153-4.

- ↑ Eyton, volume 10, p. 84-5.

- ↑ Eyton, volume 10, p. 152.

- 1 2 Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 14.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 194–5.

- ↑ Midgeley (ed.).Penkridge: Manors

- ↑ Rotuli Chartarum, p. 218.

- ↑ Midgeley (ed.).Penkridge: Churches, note anchor 155

- ↑ Midgeley (ed.).Penkridge: Manors, note anchor 135-7

- ↑ Morgan, p. 2.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 6.

- ↑ Morgan, p. 3.

- 1 2 Fletcher, p. 181.

- 1 2 Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 59.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 182–3.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 184–5.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 185.

- ↑ Morgan, p. 4.

- ↑ Blakeway, p. 323.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 173-4.

- ↑ Calendar of Charter Rolls, 1341–1417, p. 443.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 190.

- 1 2 Fletcher, p. 191.

- ↑ Lateran Regesta 147: 3 Kal. November 1410, Castel San Pietro, near Bologna. (f. 250.)

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 229.

- 1 2 Morgan, p. 6

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1408–1413, p. 280.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: College of St. Bartholomew, Tong, note anchor 1.

- ↑ Blakeway, p. 271.

- 1 2 Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 36.

- ↑ Blakeway, pp. 344–5.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, footnote 36.

- 1 2 Cranage, p. 175.

- ↑ Morgan, p. 5.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 201ff.

- 1 2 Calendar of Close Rolls, 1441–1447, p. 371.

- 1 2 Fletcher, p. 206.

- 1 2 Fletcher, p. 209.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 202-3.

- 1 2 3 Fletcher, p. 204.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 208–9.

- 1 2 Fletcher, p. 210.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 205.

- 1 2 Fletcher, p. 207.

- 1 2 Fletcher, p. 202.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 240.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 239.

- 1 2 3 Morgan, p. 7.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 51.

- 1 2 Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1441–1446, p. 412.

- ↑ Jacob, pp. 473–93.

- ↑ Gillingham, p. 53.

- ↑ Gillingham, pp. 56–64

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 211.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 212.

- 1 2 Blakeway, p. 332-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Hamilton Thompson, p. 345.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 47.

- 1 2 3 Fletcher, p. 223.

- 1 2 Fletcher, p. 222.

- ↑ Jones, B. (1964). Prebendaries: Wellington. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ June 1513, 27-30, p. 932. in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 1, 1509-1514.

- ↑ Jones, B. (1964). Archdeacons of Salop. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Jones, B. (1964). Archdeacons of Stafford. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 Blakeway, p. 336.

- 1 2 .Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 43.

- ↑ McCall, p. 1.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 183.

- 1 2 Fletcher, p. 189.

- ↑ Eyton, volume 8, p.45

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p. 422.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p. 424.

- ↑ Eyton, volume 7, p. 192.

- ↑ Blakeway, p. 326.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 203.

- ↑ Eyton, volume 2, p. 334, footnote 266.

- ↑ Calendar of Close Rolls, 1413–1419, p. 354.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 197.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 200–1.

- ↑ Plea Rolls of the Court of Common Pleas; National Archives; CP 40 / 629 at Anglo-American Legal Tradition. Entry, with Salop in the margin, goes on to next page.

- ↑ McCall, p. xxvii, footnote 2.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 27.

- ↑ Blakeway, pp. 326–7.

- 1 2 Fletcher, pp. 221–2.

- ↑ Registrum Edmundi Lacy, p. 20.

- ↑ Lateran Regesta 231: Id. March 1423, St. Peter's, Rome. (f. 77.)

- ↑ Lateran Regesta 341: 7 Id. June, Siena. (f. 208d.)

- 1 2 Fletcher, pp. 218–19.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 219.

- 1 2 Fletcher, p. 220.

- ↑ Morgan, p. 8.

- ↑ Jacob, p. 557.

- ↑ Registrum Thome Myllyng, p. 57.

- ↑ Registrum Thome Myllyng, pp. 93–4.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 226.

- 1 2 Blakeway, p. 325.

- ↑ Valor Ecclesiasticus, volume 3, p. 195.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen: Masters of Battlefield College.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 213.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 215.

- ↑ Blakeway, p. 327.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, footnote 34.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 214.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 216.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 29.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 224–5.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 226–9.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 231–2.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 232–4.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 234–5.

- ↑ Blakeway, p. 344.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 238–9.

- 1 2 Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 52.

- ↑ Hamilton Thompson, p. 269.

- ↑ Hamilton Thompson, p. 286.

- ↑ Hamilton Thompson, p. 313.

- ↑ Hamilton Thompson, p. 339.

- ↑ Hamilton Thompson, p. 346.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 54.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 55.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 245

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 248–9.

- ↑ Thorpe, S. M.; Swales, R. J. W. (1982). Bindoff, S. T. (ed.). MILDMAY, Walter (by 1523-89), of Apethorpe, Northants. and London. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Fletcher, p. 251.

- ↑ McIntyre, Elizabeth; Hawkyard, A.D.K. (1982). Bindoff, S. T. (ed.). CUPPER (COUPER), Richard (by 1519-83/84), of London; Powick and Worcester, Worcs. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Hawkyard, A.D.K. (1982). Bindoff, S. T. (ed.). PAGET, William (by 1506-63), of Beaudesert Park and Burton-upon-Trent, Staffs., West Drayton, Mdx., and London. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Fletcher, pp. 249–51.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1548–1549, p. 391.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1548–1549, p. 394.

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1548–1549, p. 395.

- ↑ Fletcher, pp. 251–3

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 257

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1549–1551, p. 136-7.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 254

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 256

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1547–1553, p. 56

- ↑ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1547–1553, p. 54

- ↑ Dale, M . K. (1982). Bindoff, S. T. (ed.). PECKHAM, Sir Edmund (by 1495-1564), of the Blackfriars, London and Denham, Bucks. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 61-2.

- 1 2 Fletcher, p. 258

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 64.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 260

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Newman, John; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2006), Shropshire, The Buildings of England, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 136–137, ISBN 0-300-12083-4

- ↑ Cf. The photograph of watercolour illustration by Edward Williams at Shropshire Archives: St Mary Magdalene Church, Battlefield: North and east Elevation and Tower

- ↑ An example is Shropshire Archives: Battlefield church, from a drawing by James Sayer.

- ↑ Brooke, pp. 11–2.

- ↑ Brooke, p. 12, footnote 1.

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 257-8

- ↑ Cranage, p. 174.

- ↑ Morgan, p. 10.

- ↑ Cf. Photograph at Shropshire Archives: Battlefield Church with scaffolding.

- ↑ Morgan, p. 11.

- ↑ Cf. The plan by Pountney Smith reproduced above from Cranage, following p. 175.

- 1 2 3 Cranage, p. 176.

- 1 2 3 Cranage, p. 173.

- ↑ Francis, Peter (2014). Shropshire War Memorials, Sites of Remembrance. YouCaxton Publications. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-909644-11-3.Francis also considers the building itself an early pre-20th century form of war memorial.

- ↑ Auden (1903), p. xv.

- ↑ Auden (1904), p. xvii-xviii.

- ↑ Gaydon, Pugh (eds.). Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen, note anchor 32.

References

- "Anglo American Legal Tradition". University of Houston. 11 January 2003. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Auden, Thomas (1903). "Our Lady of Pity". Transactions of the Shropshire Archæological and Natural History Society. 3. 3: xiv–xvi. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Auden, Thomas (1904). "Our Lady of Pity". Transactions of the Shropshire Archæological and Natural History Society. 3. 4: xiv–xvi. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Bannister, Arthur Thomas, ed. (1920). Registrum Thome Myllyng, Episcopi Herefordensis. Vol. 26. London: Canterbury and York Society. Retrieved 28 May 2018. at Internet Archive.

- Bindoff, S. T., ed. (1982). History of Parliament, 1509–1558: Members. London: History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Blakeway, John Brickdale (1889). "Battlefield". Transactions of the Shropshire Archæological and Natural History Society. 2. 1: 321–45. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Bliss, W. H.; Twemlow, J. A., eds. (1904). Calendar of Papal Registers Relating To Great Britain and Ireland, 1404–1415. Vol. 6. London: HMSO/British History Online. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Brewer, John Sherren, ed. (1920). Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, 1509-1514. Vol. 1. London: HMSO/British History Online. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Brooke, Richard (1857). Visits to Fields of Battle, in England, of the Fifteenth Century. London: John Russel Smith. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "Church of St Mary Magdalene, Battlefield, Shropshire". Churches Conservation Trust. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Cranage, D. H.S . (1903). "Battlefield Church". Transactions of the Shropshire Archæological and Natural History Society. 3. 3: 171–6. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- Eyton, Robert William (1855). Antiquities of Shropshire. Vol. 2. London: John Russel Smith. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Eyton, Robert William (1858). Antiquities of Shropshire. Vol. 7. London: John Russel Smith. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Eyton, Robert William (1859). Antiquities of Shropshire. Vol. 8. London: John Russell Smith. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Eyton, Robert William (1860). Antiquities of Shropshire. Vol. 10. London: John Russell Smith. pp. xvii–xviii. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Fletcher, W. G. D. (1903). "Battlefield College". Transactions of the Shropshire Archæological and Natural History Society. 3. 3: 177–260. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- M J Angold; G C Baugh; Marjorie M Chibnall; D C Cox; D T W Price; Margaret Tomlinson; B S Trinder (1973). "Colleges of secular canons: Battlefield, St Mary Magdalen". In Gaydon, A. T.; Pugh, R. B. (eds.). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 2. University of London & History of Parliament Trust. pp. 128–131. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2010 – via British History Online.

- Gillingham, John (1981). The Wars of the Roses: Peace and Conflict in 15th Century England (2001 ed.). Phoenix. ISBN 1-84212-274-6.

- Hamilton Thompson, A. (1910). "Certificates of the Shropshire Chantries". Transactions of the Shropshire Archæological and Natural History Society. 3. 10: 269–392. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Hardy, Thomas Duffus, ed. (1837). Rotuli Chartarum in Turri Londinensi Asservati. Vol. 1. London: uk Public Record Office. Retrieved 30 May 2018. At Bayerische Staatsbibliothek digital.

- Jacob, E. F. (1961). The Fifteenth Century. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821714-5.

- Jones, B. (1964). Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1300-1541: Volume 10, Coventry and Lichfield Diocese. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1916). Calendar of the Charter Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: 15 Edward III–5 Henry V, 1341–1417. Vol. 5. London: HMSO. Retrieved 22 May 2018. at Internet Archive.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1929). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry V, 1413–1419. Vol. 1. London: HMSO. Retrieved 25 May 2018. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1937). Calendar of the Close Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry VI, 1441–1447. Vol. 4. London: HMSO. Retrieved 25 May 2018. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1907). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1405–1408. Vol. 3. London: HMSO. Retrieved 22 May 2018. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1909). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry IV, 1408–1413. Vol. 4. London: HMSO. Retrieved 22 May 2018. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1908). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry VI, 1441–1446. Vol. 4. London: HMSO. Retrieved 16 June 2018. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1924). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward VI, 1548–1549. Vol. 2. London: HMSO. Retrieved 4 June 2018. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1925). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward VI, 1549–1551. Vol. 3. London: HMSO. Retrieved 4 June 2018. at Hathi Trust.

- Maxwell Lyte, H. C., ed. (1926). Calendar of the Patent Rolls, Preserved in the Public Record Office: Edward VI, 1547–1553. Vol. 5. London: HMSO. pp. 6v. Retrieved 4 June 2018. at Hathi Trust.

- McCall, H. B. (1910). Richmondshire Churches. London: Elliot Stock. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Midgley, L. Margaret, ed. (1959). A History of the County of Stafford. Vol. 5. London: British History Online, originally Victoria County History. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

- Morgan, Philip (11 January 2003). "The Building and Restorations of Battlefield Church". Academia. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- Owen, Hugh; Blakeway, John Brickdale (1825). A History of Shrewsbury. Vol. 2. London: Harding Leppard. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Parkes, D. (1792). Urban (pseudonym), Sylvanus (ed.). "Battlefield". The Gentleman's Magazine. 1. 62 (2): 893. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Parry, Joseph Henry, ed. (1917). Registrum Edmundi Lacy, Episcopi Herefordensis. Vol. 21. London: Canterbury and York Society. Retrieved 26 May 2018. at Internet Archive.

- "Shropshire Archives". Shropshire Council. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- Twemlow, J. A., ed. (1906). Calendar of Papal Registers Relating To Great Britain and Ireland, 1417–1431. Vol. 7. London: HMSO/British History Online. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Twemlow, J. A., ed. (1909). Calendar of Papal Registers Relating To Great Britain and Ireland, 1427–1447. Vol. 8. London: HMSO/British History Online. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- Valor Ecclesiasticus. Vol. 3. London: Record Office. 1817. Retrieved 29 May 2018.