Stereoscopic depth rendition specifies how the depth of a three-dimensional object is encoded in a stereoscopic reconstruction. It needs attention to ensure a realistic depiction of the three-dimensionality of viewed scenes and is a specific instance of the more general task of 3D rendering of objects in two-dimensional displays.

Depth in stereograms

A stereogram consists of a pair of two-dimensional frames, one for each eye. Common to both are the widths and heights of objects; their depth is encoded in the differences between right and left eye views. The geometric relationship between an object's third dimension and these position differences is presented below and depends on the location of the stereo-camera lenses and the observer's eyes. Other factors, however, contribute to the depth seen in a stereoscopic view and whether it corresponds to that in the actual object; the act of viewing a stereoscopic display often alters observers' three-dimensional perception.[1]

Stereoscopic reconstruction

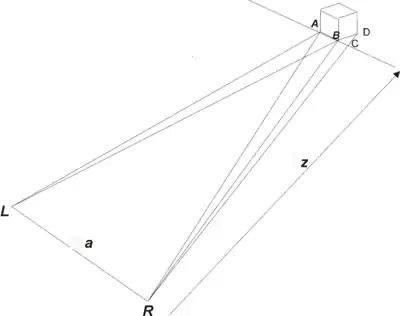

The right and left eyes' panels in a stereoscopic reconstruction are created by projection from the principal points of the twin recording camera. The geometrical situation is most clearly understood by analyzing how the screens are generated when a small cubical element of side length dx = dy = dz is photographed from a distance z with a twin camera whose lenses are a distance a apart.

In the left eye panel of the stereogram the distance AB is the representation of the front face of the cube, in the right eye panel, there is in addition BC, the representation of the cube's depth, i.e., the intercept on the screen of the rays from the cameras’ principal points to the back of the cube. This interval computes to the first order to . (To simplify the account, the right and left screens are taken to be superimposed, as they would be in a 3D display with LCD goggles.) Hence the depth/width ratio of the cube’s view, as embodied in its representation on the viewing screen, is r = a×dz/z×dx = a/z since dx=dz and depends solely on the distance of the target from the twin lenses and their separation and remains constant with scale or magnification changes. The depth/width ratio of the actual object, of course, is 1.00.

This stereogram with the cube, whose depth/width ratio had been captured with recording parameters ac and zc and embodied in the ratio BC/AB = rc=ac/zc, is now viewed by an observer with interocular separation ao at a distance zo. An overall scale change in BC/AB does not matter, but unless ro = rc, i.e., ao/zo = ac/zc. this no longer represents a cube but rather becomes, for this observer at this distance, a configuration for which

R = rc/ro ...... (1)

i.e., whose depth is R times that of a cube.

Depth rendition defined

The stereoscopic depth rendition r is a measure of the flattening or expansion in depth for a display situation and is equal to the ratio of the angles of depth and width subtended at the eye in the stereogram reconstruction of a small cubical element. A value r > 1 says that what is seen has an expanded depth relative to the actual configuration.

A numerical example will illustrate: a structure is photographed by a stereocamera with interlens separation ac = 25 cm from a distance of 1 m, zc = 100. Hence rc = ac/zc = 0.25 and on the screens the right and left representation of the cube's far edge will be separated by ¼ the distance of the width. This stereogram is now viewed from a distance of 39 cm (the magnification does not matter, only the ratio BC/AB has to have been conserved) by an observer with interocular distance 6.5 cm, i.e., ro = 6.5/39 = 0.167. According to equation (1) for this view the structure has a stereoscopic depth rendition given by R = rc/ro = 0.25/0.167 = 1.5, meaning that the observer is presented with the geometrical situation not of a cube but of a structure 1.5× as deep as it is wide. For this to become a cube ro needs to be 0.25 which occurs for an observation distance zo = 6.5/0.25 = 26 cm.

This example illustrates that a given stereoscopic presentation for a given observer gains in depth/width ratio (expands in depth) with increasing observation distance. Observers, who can fuse the twin images of the rings by voluntarily changing their convergence, can verify this by moving away and towards the viewing screen.

Homeomorphic and heteromorphic rendition

Only when the recording and viewing situations have the same r value, i.e., only when ac/zc = ao/zo will the depth/width ratios of the actual structure and its view be identical. This particular condition has been termed homeomorphic by Moritz von Rohr and was contrasted by him with the heteromorphic one in which the r values of the stereoscopic and actual views differ.[2]

Non-veridical depth: other factors

But homeomorphic rendition with geometrical parameters identical to the original does not assure that an observer's perception of depth in a stereoscopic image is the same as that in the actual three-dimensional structure. An observer judgment of the apparent disposition of objects in space depends on many factors other than the geometrical ones that pertain to the angles subtended by the components at the two eyes. This was well described in the classical study by Wallach and Zuckerman who pointed out that the depth in the view through binoculars seems foreshortened.[3] Scenes appear flattened through field glasses, even non-prismatic ones without artificial extension of the base, which provide merely overall magnification and leave the r value unchanged.

In contrast to the rules, laid out above, for calculating the geometrically defined stereoscopic depth rendition, the perceived depth involves factors — context, previous experience — that are individual and not specifiable with the same degree of generality. Chief among them is the distance at which the configuration appears to the viewer. This is by no means fixed: the subjective z is only vaguely related to the actual object distance, as is obvious in watching 3D film. Because apparent distance is the main source of judging object size (size or subjective constancy), observers' reports on the perceived depth/width ratio can deviate substantially from calculated values.[4][5][6] On the other hand, recent research confirms that the relative depths seen in three-dimensional configurations scale up more or less in proportion to the stereoscopic depth rendition arrived at within the purely geometrical framework.[7]

References

- ↑ Westheimer, Gerald (2011). "Three-dimensional displays and stereo vision". Proc. Roy. Soc. B, 278, 2241-2248. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2777.

- ↑ v. Rohr, Moritz (1907). Die Binokularen Instrumente. Berlin: Julius Springer.

- ↑ Wallach, H. and Zuckerman, C. (1963). "The constancy of stereoscopic depth". Am. J. Psychol., 76, 404–412.

- ↑ Gogel, W.C. (1960). "Perceived frontal size as a determiner of perceived binocular depth". J. Psychol., 50, 119–131.

- ↑ Foley, J.M. (1968). "Depth, size and distance in stereoscopic vision". Percept Psychophys, 3, 265–274.

- ↑ Johnston, E.B. (1991). "Systematic distortions of shape from stereopsis". Vision Research, 31, 1351–1360.

- ↑ Westheimer, Gerald (2011). "Depth rendition of three-dimensional displays", J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 28, 1185–1190.