Stonehenge in July 2007 | |

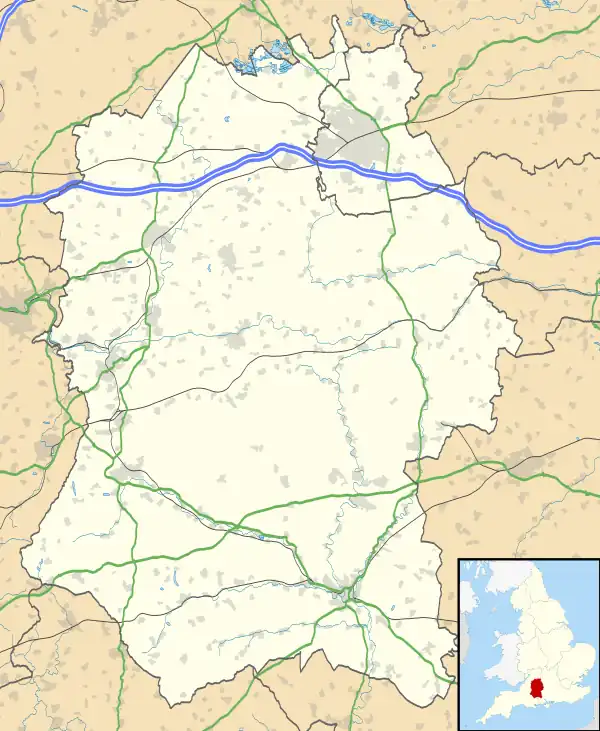

Map of Wiltshire showing the location of Stonehenge | |

| Location | Wiltshire, England |

|---|---|

| Region | Salisbury Plain |

| Coordinates | 51°10′44″N 1°49′34″W / 51.17889°N 1.82611°W |

| Type | Monument |

| Height | Each standing stone was around 13 ft (4.0 m) high |

| History | |

| Material | Sarsen, Bluestone |

| Founded | Bronze Age |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | Multiple |

| Ownership | The Crown |

| Management | English Heritage |

| Website | www |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii |

| Designated | 1986 (10th session) |

| Part of | Stonehenge, Avebury and Associated Sites |

| Reference no. | 373 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Official name | Stonehenge, the Avenue, and three barrows adjacent to the Avenue forming part of a round barrow cemetery on Countess Farm[1] |

| Designated | 18 August 1882 |

| Reference no. | 1010140[1] |

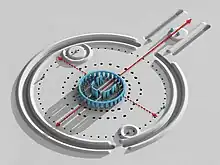

3D model (click to interact) | |

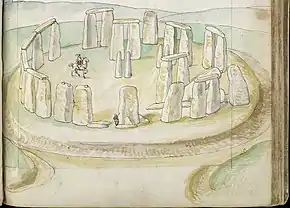

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, two miles (3 km) west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around 13 feet (4.0 m) high, seven feet (2.1 m) wide, and weighing around 25 tons, topped by connecting horizontal lintel stones. Inside is a ring of smaller bluestones. Inside these are free-standing trilithons, two bulkier vertical sarsens joined by one lintel. The whole monument, now ruinous, is aligned towards the sunrise on the summer solstice and sunset on the winter solstice. The stones are set within earthworks in the middle of the densest complex of Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments in England, including several hundred tumuli (burial mounds).[2]

Archaeologists believe that Stonehenge was constructed in several phases from around 3100 BC to 1600 BC, with the circle of large sarsen stones placed between 2600 BC and 2400 BC. The surrounding circular earth bank and ditch, which constitute the earliest phase of the monument, have been dated to about 3100 BC. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the bluestones were given their current positions between 2400 and 2200 BC,[3] although they may have been at the site as early as 3000 BC.[4][5][6]

One of the most famous landmarks in the United Kingdom, Stonehenge is regarded as a British cultural icon.[7] It has been a legally protected scheduled monument since 1882,[1] when legislation to protect historic monuments was first successfully introduced in Britain. The site and its surroundings were added to UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites in 1986. Stonehenge is owned by the Crown and managed by English Heritage; the surrounding land is owned by the National Trust.[8][9]

Stonehenge could have been a burial ground from its earliest beginnings.[10] Deposits containing human bone date from as early as 3000 BC, when the ditch and bank were first dug, and continued for at least another 500 years.[11]

Etymology

The Oxford English Dictionary cites Ælfric's tenth-century glossary, in which henge-cliff is given the meaning 'precipice', or stone; thus, the stanenges or Stanheng "not far from Salisbury" recorded by eleventh-century writers are "stones supported in the air". In 1740, William Stukeley notes: "Pendulous rocks are now called henges in Yorkshire ... I doubt not, Stonehenge in Saxon signifies the hanging stones."[12] Christopher Chippindale's Stonehenge Complete gives the derivation of the name Stonehenge as coming from the Old English words stān 'stone', and either hencg 'hinge' (because the stone lintels hinge on the upright stones) or hen(c)en 'to hang' or 'gallows' or 'instrument of torture' (though elsewhere in his book, Chippindale cites the 'suspended stones' etymology).[13]

The "henge" portion has given its name to a class of monuments known as henges.[12] Archaeologists define henges as earthworks consisting of a circular banked enclosure with an internal ditch.[14] As often happens in archaeological terminology, this is a holdover from antiquarian use.

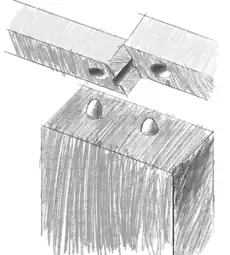

Despite being contemporary with true Neolithic henges and stone circles, Stonehenge is in many ways atypical – for example, at more than 24 feet (7.3 m) tall, its extant trilithons' lintels, held in place with mortise and tenon joints, make it unique.[15][16]

Early history

Mike Parker Pearson, leader of the Stonehenge Riverside Project based around Durrington Walls, noted that Stonehenge appears to have been associated with burial from the earliest period of its existence:

Stonehenge was a place of burial from its beginning to its zenith in the mid third millennium B.C. The cremation burial dating to Stonehenge's sarsen stones phase is likely just one of many from this later period of the monument's use and demonstrates that it was still very much a domain of the dead.[11]

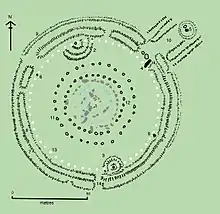

Stonehenge evolved in several construction phases spanning at least 1500 years. There is evidence of large-scale construction on and around the monument that perhaps extends the landscape's time frame to 6500 years. Dating and understanding the various phases of activity are complicated by disturbance of the natural chalk by periglacial effects and animal burrowing, poor quality early excavation records, and a lack of accurate, scientifically verified dates. The modern phasing most generally agreed to by archaeologists is detailed below. Features mentioned in the text are numbered and shown on the plan, right.

Before the monument (from 8000 BC)

Archaeologists have found four, or possibly five, large Mesolithic postholes (one may have been a natural tree throw), which date to around 8000 BC, beneath the nearby old tourist car-park in use until 2013. These held pine posts around two feet six inches (0.75 m) in diameter, which were erected and eventually rotted in situ. Three of the posts (and possibly four) were in an east–west alignment which may have had ritual significance.[17] Another Mesolithic astronomical site in Britain is the Warren Field site in Aberdeenshire, which is considered the world's oldest lunisolar calendar, corrected yearly by observing the midwinter solstice.[18] Similar but later sites have been found in Scandinavia.[19] A settlement that may have been contemporaneous with the posts has been found at Blick Mead, a reliable year-round spring one mile (1.6 km) from Stonehenge.[20][21]

Salisbury Plain was then still wooded, but 4,000 years later, during the earlier Neolithic, people built a causewayed enclosure at Robin Hood's Ball, and long barrow tombs in the surrounding landscape. In approximately 3500 BC, a Stonehenge Cursus was built 2,300 feet (700 m) north of the site as the first farmers began to clear the trees and develop the area. Other previously overlooked stone or wooden structures and burial mounds may date as far back as 4000 BC.[22][23] Charcoal from the 'Blick Mead' camp 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from Stonehenge (near the Vespasian's Camp site) has been dated to 4000 BC.[24] The University of Buckingham's Humanities Research Institute believes that the community who built Stonehenge lived here over a period of several millennia, making it potentially "one of the pivotal places in the history of the Stonehenge landscape."[20]

Stonehenge 1 (c. 3100 BC)

The first monument consisted of a circular bank and ditch enclosure made of Late Cretaceous (Santonian Age) Seaford chalk, measuring about 360 feet (110 m) in diameter, with a large entrance to the north east and a smaller one to the south. It stood in open grassland on a slightly sloping spot.[25] The builders placed the bones of deer and oxen in the bottom of the ditch, as well as some worked flint tools. The bones were considerably older than the antler picks used to dig the ditch, and the people who buried them had looked after them for some time prior to burial. The ditch was continuous but had been dug in sections, like the ditches of the earlier causewayed enclosures in the area. The chalk dug from the ditch was piled up to form the bank. This first stage is dated to around 3100 BC, after which the ditch began to silt up naturally. Within the outer edge of the enclosed area is a circle of 56 pits, each about 3.3 feet (1 m) in diameter, known as the Aubrey holes after John Aubrey, the seventeenth-century antiquarian who was thought to have first identified them. These pits and the bank and ditch together are known as the Palisade or Gate Ditch.[26] The pits may have contained standing timbers creating a timber circle, although there is no excavated evidence of them. A recent excavation has suggested that the Aubrey Holes may have originally been used to erect a bluestone circle.[27] If this were the case, it would advance the earliest known stone structure at the monument by some 500 years.

In 2013 a team of archaeologists, led by Mike Parker Pearson, excavated more than 50,000 cremated bone fragments, from 63 individuals, buried at Stonehenge.[4][5] These remains had originally been buried individually in the Aubrey holes, exhumed during a previous excavation conducted by William Hawley in 1920, been considered unimportant by him, and subsequently re-interred together in one hole, Aubrey Hole 7, in 1935.[28] Physical and chemical analysis of the remains has shown that the cremated were almost equally men and women, and included some children.[4][5] As there was evidence of the underlying chalk beneath the graves being crushed by substantial weight, the team concluded that the first bluestones brought from Wales were probably used as grave markers.[4][5] Radiocarbon dating of the remains has put the date of the site 500 years earlier than previously estimated, to around 3000 BC.[4][5] A 2018 study of the strontium content of the bones found that many of the individuals buried there around the time of construction had probably come from near the source of the bluestone in Wales and had not extensively lived in the area of Stonehenge before death.[29]

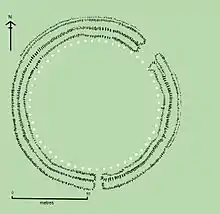

Between 2017 and 2021, studies by Professor Parker Pearson (UCL) and his team suggested that the bluestones used in Stonehenge had been moved there following dismantling of a stone circle of identical size to the first known Stonehenge circle (110m) at the Welsh site of Waun Mawn in the Preseli Hills.[30][31] It had contained bluestones, one of which showed evidence of having been reused in Stonehenge. The stone was identified by its unusual pentagonal shape and by luminescence soil dating from the filled-in sockets which showed the circle had been erected around 3400-3200 BC, and dismantled around 300–400 years later, consistent with the dates attributed to the creation of Stonehenge.[30][31] The cessation of human activity in that area at the same time suggested migration as a reason, but it is believed that other stones may have come from other sources.[30][31]

Stonehenge 2 (c. 2900 BC)

The second phase of construction occurred approximately between 2900 and 2600 BC.[32] The number of postholes dating to the early third millennium BC suggests that some form of timber structure was built within the enclosure during this period. Further standing timbers were placed at the northeast entrance, and a parallel alignment of posts ran inwards from the southern entrance. The postholes are smaller than the Aubrey Holes, being only around 16 inches (0.4 m) in diameter, and are much less regularly spaced. The bank was purposely reduced in height and the ditch continued to silt up. At least twenty-five of the Aubrey Holes are known to have contained later, intrusive, cremation burials dating to the two centuries after the monument's inception. It seems that whatever the holes' initial function, it changed to become a funerary one during Phase two. Thirty further cremations were placed in the enclosure's ditch and at other points within the monument, mostly in the eastern half. Stonehenge is therefore interpreted as functioning as an enclosed cremation cemetery at this time,[32] the earliest known cremation cemetery in the British Isles. Fragments of unburnt human bone have also been found in the ditch-fill. Dating evidence is provided by the late Neolithic grooved ware pottery that has been found in connection with the features from this phase.

Stonehenge 3 I (c. 2600 BC)

Archaeological excavation has indicated that around 2600 BC, the builders abandoned timber in favour of stone and dug two concentric arrays of holes (the Q and R Holes) in the centre of the site. These stone sockets are only partly known (hence on present evidence are sometimes described as forming 'crescents'); however, they could be the remains of a double ring. Again, there is little firm dating evidence for this phase. The holes held up to 80 standing stones (shown blue on the plan), only 43 of which can be traced today. It is generally accepted that the bluestones (some of which are made of dolerite, an igneous rock), were transported by the builders from the Preseli Hills, 150 miles (240 km) away in modern-day Pembrokeshire in Wales. Another theory is that they were brought much nearer to the site as glacial erratics by the Irish Sea Glacier[33] although there is no evidence of glacial deposition within southern central England.[34] A 2019 publication announced that evidence of Megalithic quarrying had been found at quarries in Wales identified as a source of Stonehenge's bluestone, indicating that the bluestone was quarried by human agency and not transported by glacial action.[35]

The long-distance human transport theory was bolstered in 2011 by the discovery of a megalithic bluestone quarry at Craig Rhos-y-felin, near Crymych in Pembrokeshire, which is the most likely place for some of the stones to have been obtained.[34] Other standing stones may well have been small sarsens (sandstone), used later as lintels. The stones, which weighed about two tons, could have been moved by lifting and carrying them on rows of poles and rectangular frameworks of poles, as recorded in China, Japan and India. It is not known whether the stones were taken directly from their quarries to Salisbury Plain or were the result of the removal of a venerated stone circle from Preseli to Salisbury Plain to "merge two sacred centres into one, to unify two politically separate regions, or to legitimise the ancestral identity of migrants moving from one region to another".[34] Evidence of a 110-metre (360 ft) stone circle at Waun Mawn near Preseli, which could have contained some or all of the stones in Stonehenge, has been found, including a hole from a rock that matches the unusual cross-section of a Stonehenge bluestone "like a key in a lock".[36] Each monolith measures around 6.6 feet (2 m) in height, between 3.3 and 4.9 ft (1 and 1.5 m) wide and around 2.6 feet (0.8 m) thick. What was to become known as the Altar Stone is almost certainly derived from the Senni Beds, perhaps from 50 miles (80 kilometres) east of the Preseli Hills in the Brecon Beacons.[34]

The north-eastern entrance was widened at this time, with the result that it precisely matched the direction of the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset of the period. This phase of the monument was abandoned unfinished, however; the small standing stones were apparently removed and the Q and R holes purposefully backfilled.

The Heel Stone, a Tertiary sandstone, may also have been erected outside the north-eastern entrance during this period. It cannot be accurately dated and may have been installed at any time during phase 3. At first, it was accompanied by a second stone, which is no longer visible. Two, or possibly three, large portal stones were set up just inside the north-eastern entrance, of which only one, the fallen Slaughter Stone, 16 feet (4.9 m) long, now remains. Other features, loosely dated to phase 3, include the four Station Stones, two of which stood atop mounds. The mounds are known as "barrows" although they do not contain burials. Stonehenge Avenue, a parallel pair of ditches and banks leading two miles (3 km) to the River Avon, was also added.

Stonehenge 3 II (2600 BC to 2400 BC)

During the next major phase of activity, 30 enormous Oligocene–Miocene sarsen stones (shown grey on the plan) were brought to the site. They came from a quarry around 16 miles (26 km) north of Stonehenge, in West Woods, Wiltshire.[37] The stones were dressed and fashioned with mortise and tenon joints before 30 sarsens were erected as a 108-foot (33 m) diameter circle of standing stones, with a ring of 30 lintel stones resting on top. The lintels were fitted to one another using tongue and groove joints – a woodworking method, again. Each standing stone was around 13 feet (4.1 m) high, 6.9 feet (2.1 m) wide and weighed around 25 tons. Each had clearly been worked with the final visual effect in mind: The orthostats widen slightly towards the top in order that their perspective remains constant when viewed from the ground, while the lintel stones curve slightly to continue the circular appearance of the earlier monument.

The inward-facing surfaces of the stones are smoother and more finely worked than the outer surfaces. The average thickness of the stones is 3.6 feet (1.1 m) and the average distance between them is 3.3 feet (1 m). A total of 75 stones would have been needed to complete the circle (60 stones) and the trilithon horseshoe (15 stones). It was thought the ring might have been left incomplete, but an exceptionally dry summer in 2013 revealed patches of parched grass which may correspond to the location of missing sarsens.[38] The lintel stones are each around 10 feet (3.2 m) long, 3.3 feet (1 m) wide and 2.6 feet (0.8 m) thick. The tops of the lintels are 16 feet (4.9 m) above the ground.

Within this circle stood five trilithons of dressed sarsen stone arranged in a horseshoe shape 45 feet (13.7 m) across, with its open end facing northeast. These huge stones, ten uprights and five lintels, weigh up to 50 tons each. They were linked using complex jointing. They are arranged symmetrically. The smallest pair of trilithons were around 20 feet (6 m) tall, the next pair a little higher, and the largest, single trilithon in the south-west corner would have been 24 feet (7.3 m) tall. Only one upright from the Great Trilithon still stands, of which 22 feet (6.7 m) is visible and a further 7.9 feet (2.4 m) is below ground. The images of a 'dagger' and 14 'axeheads' have been carved on one of the sarsens, known as stone 53; further carvings of axeheads have been seen on the outer faces of stones 3, 4, and 5. The carvings are difficult to date but are morphologically similar to late Bronze Age weapons. Early 21st century laser scanning of the carvings supports this interpretation. The pair of trilithons in the north east are smallest, measuring around 20 feet (6 m) in height; the largest, which is in the south-west of the horseshoe, is almost 25 feet (7.5 m) tall.

This ambitious phase has been radiocarbon dated to between 2600 and 2400 BC,[39] slightly earlier than the Stonehenge Archer, discovered in the outer ditch of the monument in 1978, and the two sets of burials, known as the Amesbury Archer and the Boscombe Bowmen, discovered three miles (5 km) to the west. Analysis of animal teeth found two miles (3 km) away at Durrington Walls, thought by Parker Pearson to be the 'builders camp', suggests that, during some period between 2600 and 2400 BC, as many as 4,000 people gathered at the site for the mid-winter and mid-summer festivals; the evidence showed that the animals had been slaughtered around nine months or 15 months after their spring birth. Strontium isotope analysis of the animal teeth showed that some had been brought from as far afield as the Scottish Highlands for the celebrations.[5][6]

At about the same time, a large timber circle and a second avenue were constructed at Durrington Walls overlooking the River Avon. The timber circle was orientated towards the rising Sun on the midwinter solstice, opposing the solar alignments at Stonehenge. The avenue was aligned with the setting Sun on the summer solstice and led from the river to the timber circle. Evidence of huge fires on the banks of the Avon between the two avenues also suggests that both circles were linked. They were perhaps used as a procession route on the longest and shortest days of the year. Parker Pearson speculates that the wooden circle at Durrington Walls was the centre of a 'land of the living', whilst the stone circle represented a 'land of the dead', with the Avon serving as a journey between the two.[40]

Stonehenge 3 III (2400 BC to 2280 BC)

Later in the Bronze Age, although the exact details of activities during this period are still unclear, the bluestones appear to have been re-erected. They were placed within the outer sarsen circle and may have been trimmed in some way. Like the sarsens, a few have timber-working style cuts in them suggesting that, during this phase, they may have been linked with lintels and were part of a larger structure.

Stonehenge 3 IV (2280 BC to 1930 BC)

This phase saw further rearrangement of the bluestones. They were arranged in a circle between the two rings of sarsens and in an oval at the centre of the inner ring. Some archaeologists argue that some of these bluestones were from a second group brought from Wales. All the stones formed well-spaced uprights without any of the linking lintels inferred in Stonehenge 3 III. The Altar Stone may have been moved within the oval at this time and re-erected vertically. Although this would seem the most impressive phase of work, Stonehenge 3 IV was rather shabbily built compared to its immediate predecessors, as the newly re-installed bluestones were not well-founded and began to fall over. However, only minor changes were made after this phase.

Stonehenge 3 V (1930 BC to 1600 BC)

Soon afterwards, the northeastern section of the Phase 3 IV bluestone circle was removed, creating a horseshoe-shaped setting (the Bluestone Horseshoe) which mirrored the shape of the central sarsen Trilithons. This phase is contemporary with the Seahenge site in Norfolk.

After the monument (1600 BC on)

The Y and Z Holes are the last known construction at Stonehenge, built about 1600 BC, and the last usage of it was probably during the Iron Age. Roman coins and medieval artefacts have all been found in or around the monument but it is unknown if the monument was in continuous use throughout British prehistory and beyond, or exactly how it would have been used. Notable is the massive Iron Age hillfort known as Vespasian's Camp (despite its name, not a Roman site) built alongside the Avenue near the Avon. A decapitated seventh-century Saxon man was excavated from Stonehenge in 1923.[41] The site was known to scholars during the Middle Ages and since then it has been studied and adopted by numerous groups.[42]

Function and construction

Stonehenge was produced by a culture that left no written records. Many aspects of Stonehenge, such as how it was built and for what purposes it was used, remain subject to debate. A number of myths surround the stones.[43] The site, specifically the great trilithon, the encompassing horseshoe arrangement of the five central trilithons, the heel stone, and the embanked avenue, are aligned to the sunset of the winter solstice and the opposing sunrise of the summer solstice.[44][45] A natural landform at the monument's location followed this line, and may have inspired its construction.[46] The excavated remains of culled animal bones suggest that people may have gathered at the site for the winter rather than the summer.[47] Further astronomical associations, and the precise astronomical significance of the site for its people, are a matter of speculation and debate.

There is little or no direct evidence revealing the construction techniques used by the Stonehenge builders. Over the years, various authors have suggested that supernatural or anachronistic methods were used, usually asserting that the stones were impossible to move otherwise due to their massive size. However, conventional techniques, using Neolithic technology as basic as shear legs, have been demonstrably effective at moving and placing stones of a similar size.[48] The most common theory of how prehistoric people moved megaliths has them creating a track of logs which the large stones were rolled along.[49] Another megalith transport theory involves the use of a type of sleigh running on a track greased with animal fat.[49] Such an experiment with a sleigh carrying a 40-ton slab of stone was successfully conducted near Stonehenge in 1995. A team of more than 100 workers managed to push and pull the slab along the 18-mile (29 km) journey from the Marlborough Downs.[49]

Proposed functions for the site include usage as an astronomical observatory or as a religious site. In the 1960s Gerald Hawkins described in detail how the site was apparently set out to observe the Sun and Moon over a recurring 56-year cycle.[50] More recently two major new theories have been proposed. Geoffrey Wainwright, president of the Society of Antiquaries of London, and Timothy Darvill, of Bournemouth University, have suggested that Stonehenge was a place of healing—the primeval equivalent of Lourdes.[51] They argue that this accounts for the high number of burials in the area and for the evidence of trauma deformity in some of the graves. However, they do concede that the site was probably multifunctional and used for ancestor worship as well.[52] Isotope analysis indicates that some of the buried individuals were from other regions. A teenage boy buried approximately 1550 BC was raised near the Mediterranean Sea; a metal worker from 2300 BC dubbed the "Amesbury Archer" grew up near the Alpine foothills of Germany; and the "Boscombe Bowmen" probably arrived from Wales or Brittany, France.[53]

On the other hand, Mike Parker Pearson of Sheffield University has suggested that Stonehenge was part of a ritual landscape and was joined to Durrington Walls by their corresponding avenues and the River Avon. He suggests that the area around Durrington Walls Henge was a place of the living, whilst Stonehenge was a domain of the dead. A journey along the Avon to reach Stonehenge was part of a ritual passage from life to death, to celebrate past ancestors and the recently deceased.[40] Both explanations were first mooted in the twelfth century by Geoffrey of Monmouth, who extolled the curative properties of the stones and was also the first to advance the idea that Stonehenge was constructed as a funerary monument. Whatever religious, mystical or spiritual elements were central to Stonehenge, its design includes a celestial observatory function, which might have allowed prediction of eclipse, solstice, equinox and other celestial events important to a contemporary religion.[50]

There are other hypotheses and theories. According to a team of British researchers led by Mike Parker Pearson of the University of Sheffield, Stonehenge may have been built as a symbol of "peace and unity", indicated in part by the fact that at the time of its construction, Britain's Neolithic people were experiencing a period of cultural unification.[43][54]

Stonehenge megaliths include smaller bluestones and larger sarsens (a term for silicified sandstone boulders found in the chalk downs of southern England). The bluestones are composed of dolerite, tuff, rhyolite, or sandstone. The igneous bluestones appear to have originated in the Preseli hills of southwestern Wales about 140 miles (230 km) from the monument.[34] The sandstone Altar Stone may have originated in east Wales. Recent analysis has indicated the sarsens originated from West Woods, about 16 miles (26 km) from the monument.[37] Researchers from the Royal College of Art in London have discovered that the monument's igneous bluestones possess "unusual acoustic properties" – when struck they respond with a "loud clanging noise". Rocks with such acoustic properties are frequent in the Carn Melyn ridge of Presili; the Presili village of Maenclochog (Welsh for bell or ringing stones), used local bluestones as church bells until the 18th century. According to the team, these acoustic properties could explain why certain bluestones were hauled such a long distance, a major technical accomplishment at the time. In certain ancient cultures, rocks that ring out, known as lithophonic rocks, were believed to contain mystic or healing powers, and Stonehenge has a history of association with rituals. The presence of these "ringing rocks" seems to support the hypothesis that Stonehenge was a "place for healing" put forward by Darvill, who consulted with the researchers.[55]

DNA studies and historical context

Researchers studying DNA extracted from Neolithic human remains across Britain determined that the ancestors of the people who built Stonehenge were early European farmers who came from the Eastern Mediterranean, travelling west from there, as well as Western hunter-gatherers from western Europe. DNA studies indicate that early European farmers had a predominantly Aegean ancestry, although their agricultural techniques seem to have come originally from Anatolia. These Aegean farmers moved to Iberia before heading north, reaching Britain in about 4,000 BC.[57][58] Neolithic individuals in the British Isles were close to Iberian and Central European Early and Middle Neolithic populations, modelled as having about 75% ancestry from Aegean farmers with the rest coming from Western Hunter-Gatherers in continental Europe.[58] They subsequently replaced most of the hunter-gatherer population in the British Isles without mixing much with them.[59] At that time, Britain was inhabited by groups of hunter-gatherers who were the first inhabitants of the island after the last Ice Age ended about 11,700 years ago.[60] Despite their mostly Aegean ancestry, the paternal (Y-DNA) lineages of Neolithic farmers in Britain were almost exclusively of Western Hunter-Gatherer origin.[61] This was also the case among other megalithic-building populations in northwest Europe,[62][lower-alpha 1][63][lower-alpha 2] meaning that these populations were descended from a mixture of hunter-gatherer males and farmer females.[lower-alpha 3]

This mixture appears to have happened primarily on the continent before the Neolithic farmers migrated to Britain.[57][58] The dominance of Western Hunter-Gatherer male lineages in Britain and northwest Europe is also reflected in a general 'resurgence' of hunter-gatherer ancestry, predominantly from males, across western and central Europe in the Middle Neolithic.[64][lower-alpha 4]

The Bell Beaker people arrived later, around 2,500 BC, migrating from mainland Europe. The earliest British beakers, most likely speakers of Indo-European languages whose ancestors migrated from the Pontic–Caspian steppe,[60] were similar to those from the Rhine.[65] There was again a large population replacement in Britain.[66] More than 90% of Britain's Neolithic gene pool was replaced with the arrival of the Bell Beaker people,[67] who had approximately 50% WSH ancestry.[68] The Bell Beakers also left their impact on Stonehenge construction,[69] constructing Stonehenge III. They are also associated with the Wessex culture.

The latter appears to have had wide-ranging trade links with continental Europe, going as far as Mycenaean Greece. The wealth from such trade probably permitted the Wessex people to construct the second and third (megalithic) phases of Stonehenge and also indicates a powerful form of social organisation.[70]

The Bell Beakers were also associated with the tin trade, which was Britain's only unique export at the time. Tin was important because it was used to turn copper into bronze, and the Beakers derived much wealth from this.[71]

There is evidence to suggest that despite the introduction of farming in the British Isles, the practice of cereal cultivation fell out of favor between 3300 and 1500 BC, with much of the population reverting to a pastoralist subsistence pattern focused on hazelnut gathering and pig and cattle rearing. A majority of the major phases of Stonehenge's construction took place during such a period where evidence of large-scale agriculture is equivocal. Similar associations between non-cereal farming subsistence patterns and monumental construction are also seen at Poverty Point and Sannai Maruyama.[72]

Modern history

Folklore

.jpg.webp)

"Heel Stone", "Friar's Heel", or "Sun-Stone"

The Heel Stone lies northeast of the sarsen circle, beside the end portion of Stonehenge Avenue.[73] It is a rough stone, 16 feet (4.9 m) above ground, leaning inwards towards the stone circle.[73] It has been known by many names in the past, including "Friar's Heel" and "Sun-stone".[74][75] At the Summer solstice an observer standing within the stone circle, looking northeast through the entrance, would see the Sun rise in the approximate direction of the Heel Stone, and the Sun has often been photographed over it.

A folk tale relates the origin of the Friar's Heel reference.[76][77]

The Devil bought the stones from a woman in Ireland, wrapped them up, and brought them to Salisbury plain. One of the stones fell into the Avon, the rest were carried to the plain. The Devil then cried out, "No-one will ever find out how these stones came here!" A friar replied, "That's what you think!", whereupon the Devil threw one of the stones at him and struck him on the heel. The stone stuck in the ground and is still there.[78]

Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable attributes this tale to Geoffrey of Monmouth, but though book eight of Geoffrey's Historia Regum Britanniae does describe how Stonehenge was built, the two stories are entirely different.

The name is not unique; there was a monolith with the same name recorded in the nineteenth century by antiquarian Charles Warne at Long Bredy in Dorset.[79]

Arthurian legend

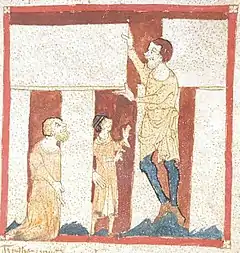

The twelfth-century Historia Regum Britanniae ("History of the Kings of Britain"), by Geoffrey of Monmouth, includes a fanciful story of how Stonehenge was brought from Ireland with the help of the wizard Merlin.[80] Geoffrey's story spread widely, with variations of it appearing in adaptations of his work, such as Wace's Norman French Roman de Brut, Layamon's Middle English Brut, and the Welsh Brut y Brenhinedd.

According to the tale, the stones of Stonehenge were healing stones, which giants had brought from Africa to Ireland. They had been raised on Mount Killaraus to form a stone circle, known as the Giant's Ring or Giant's Round. The fifth-century king Aurelius Ambrosius wished to build a great memorial to the British Celtic nobles slain by the Saxons at Salisbury. Merlin advised him to use the Giant's Ring. The king sent Merlin and Uther Pendragon (King Arthur's father) with 15,000 men to bring it from Ireland. They defeated an Irish army led by Gillomanius, but were unable to move the huge stones. With Merlin's help, they transported the stones to Britain and re-erected them as they had stood.[81] Mount Killaraus may refer to the Hill of Uisneach.[82] Although the tale is fiction, archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson suggests it may hold a "grain of truth", as evidence suggests the Stonehenge bluestones were brought from the Waun Mawn stone circle on the Irish Sea coast of Wales.[83]

Another legend tells how the invading Saxon king Hengist invited British Celtic warriors to a feast but treacherously ordered his men to massacre the guests, killing 420 of them. Hengist erected Stonehenge on the site to show his remorse for the deed.[84]

Sixteenth century to present

Stonehenge has changed ownership several times since King Henry VIII acquired Amesbury Abbey and its surrounding lands. In 1540 Henry gave the estate to the Earl of Hertford. It subsequently passed to Lord Carleton and then the Marquess of Queensberry. The Antrobus family of Cheshire bought the estate in 1824. During the First World War an aerodrome (Royal Flying Corps "No. 1 School of Aerial Navigation and Bomb Dropping")[85] was built on the downs just to the west of the circle and, in the dry valley at Stonehenge Bottom, a main road junction was built, along with several cottages and a cafe. Stonehenge was one of several lots put up for auction in 1915 by Sir Cosmo Gordon Antrobus, soon after he had inherited the estate from his brother. The auction by Knight Frank & Rutley estate agents in Salisbury was held on 21 September 1915 and included "Lot 15. Stonehenge with about 30 acres, 2 rods, 37 perches [12.44 ha] of adjoining downland."[86]

In 1915, Cecil Chubb bought the site for £6,600 (£562,700 in 2024) and gave it to the nation three years later, with certain conditions attached. Although it has been speculated that he purchased it at the suggestion of – or even as a present for – his wife, in fact he bought it on a whim, as he believed a local man should be the new owner.[86]

In the late 1920s a nationwide appeal was launched to save Stonehenge from the encroachment of the modern buildings that had begun to rise around it.[87] By 1928 the land around the monument had been purchased with the appeal donations and given to the National Trust to preserve. The buildings were removed (although the roads were not), and the land returned to agriculture. More recently the land has been part of a grassland reversion scheme, returning the surrounding fields to native chalk grassland.[88]

Neopaganism

During the twentieth century, Stonehenge began to revive as a place of religious significance, this time by adherents of Neopaganism and New Age beliefs, particularly the Neo-druids. The historian Ronald Hutton would later remark that "it was a great, and potentially uncomfortable, irony that modern Druids had arrived at Stonehenge just as archaeologists were evicting the ancient Druids from it."[89] The first such Neo-druidic group to make use of the megalithic monument was the Ancient Order of Druids, who performed a mass initiation ceremony there in August 1905, in which they admitted 259 new members into their organisation. This assembly was largely ridiculed in the press, who mocked the fact that the Neo-druids were dressed up in costumes consisting of white robes and fake beards.[90]

Between 1972 and 1984, Stonehenge was the site of the Stonehenge Free Festival. After the Battle of the Beanfield between police and New Age travellers in 1985, this use of the site was stopped for several years and ritual use of Stonehenge is now heavily restricted.[91] Some Druids have arranged an assembling of monuments styled on Stonehenge in other parts of the world as a form of Druidist worship.[92]

The earlier rituals were complemented by the Stonehenge Free Festival, loosely organised by the Polytantric Circle, held between 1972 and 1984, during which time the number of midsummer visitors had risen to around 30,000.[93] However, in 1985 the site was closed to festivalgoers by a High Court injunction.[94] A consequence of the end of the festival in 1985 was the violent confrontation between the police and New Age travellers that became known as the Battle of the Beanfield when police blockaded a convoy of travellers to prevent them from approaching Stonehenge. Beginning in 1985, the year of the Battle, no access was allowed into the stones at Stonehenge for any religious reason. This "exclusion-zone" policy continued for almost fifteen years: until just before the arrival of the twenty-first century, visitors were not allowed to go into the stones at times of religious significance, the winter and summer solstices, and the vernal and autumnal equinoxes.[95]

However, following a European Court of Human Rights ruling obtained by campaigners such as Arthur Uther Pendragon, the restrictions were lifted.[94] The ruling recognized that members of any genuine religion have a right to worship in their own church, and Stonehenge is a place of worship to Neo-Druids, Pagans and other "Earth based' or 'old' religions.[96] Meetings were organised by the National Trust and others to discuss the arrangements.[97] In 1998, a party of 100 people was allowed access and these included astronomers, archaeologists, Druids, locals, pagans and travellers.[97] In 2000, an open summer solstice event was held and about seven thousand people attended.[97] In 2001, the numbers increased to about 10,000.[97]

Setting and access

When Stonehenge was first opened to the public it was possible to walk among and even climb on the stones, but the stones were roped off in 1977 as a result of serious erosion.[98] Visitors are no longer permitted to touch the stones but are able to walk around the monument from a short distance away. English Heritage does, however, permit access during the summer and winter solstice, and the spring and autumn equinox. Additionally, visitors can make special bookings to access the stones throughout the year.[99] Local residents are still entitled to free admission to Stonehenge because of an agreement concerning the moving of a right of way.[100]

The access situation and the proximity of the two roads have drawn widespread criticism, highlighted by a 2006 National Geographic survey. In the survey of conditions at 94 leading World Heritage Sites, 400 conservation and tourism experts ranked Stonehenge 75th in the list of destinations, declaring it to be "in moderate trouble".[101]

As motorised traffic increased, the setting of the monument began to be affected by the proximity of the two roads on either side—the A344 to Shrewton on the north side, and the A303 to Winterbourne Stoke to the south. Plans to upgrade the A303 and close the A344 to restore the vista from the stones have been considered since the monument became a World Heritage Site. However, the controversy surrounding expensive re-routing of the roads has led to the scheme being cancelled on multiple occasions. On 6 December 2007, it was announced that extensive plans to build Stonehenge road tunnel under the landscape and create a permanent visitors' centre had been cancelled.[102]

On 13 May 2009, the government gave approval for a £25 million scheme to create a smaller visitors' centre and close the A344, although this was dependent on funding and local authority planning consent.[103] On 20 January 2010 Wiltshire Council granted planning permission for a centre 1.5 mi (2.4 kilometres) to the west and English Heritage confirmed that funds to build it would be available, supported by a £10m grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund.[104] On 23 June 2013 the A344 was closed to begin the work of removing the section of road and replacing it with grass.[105][106] The centre, designed by Denton Corker Marshall, opened to the public on 18 December 2013.[107]

Archaeological research and restoration

.jpg.webp)

1600–1900

Throughout recorded history, Stonehenge and its surrounding monuments have attracted attention from antiquarians and archaeologists. John Aubrey was one of the first to examine the site with a scientific eye in 1666, and in his plan of the monument, he recorded the pits that now bear his name, the Aubrey holes. William Stukeley continued Aubrey's work in the early eighteenth century, but took an interest in the surrounding monuments as well, identifying (somewhat incorrectly) the Cursus and the Avenue. He also began the excavation of many of the barrows in the area, and it was his interpretation of the landscape that associated it with the Druids.[108] Stukeley was so fascinated with Druids that he originally named Disc Barrows as Druids' Barrows.

The most accurate early plan of Stonehenge was that made by Bath architect John Wood in 1740.[109] His original annotated survey has recently been computer redrawn and published.[110] Importantly Wood's plan was made before the collapse of the southwest trilithon, which fell in 1797 and was restored in 1958.[111]

William Cunnington was the next to tackle the area in the early nineteenth century. He excavated some 24 barrows before digging in and around the stones and discovered charred wood, animal bones, pottery and urns. He also identified the hole in which the Slaughter Stone once stood. Richard Colt Hoare supported Cunnington's work and excavated some 379 barrows on Salisbury Plain including on some 200 in the area around the Stones, some excavated in conjunction with William Coxe. To alert future diggers to their work they were careful to leave initialled metal tokens in each barrow they opened. Cunnington's finds are displayed at the Wiltshire Museum. In 1877 Charles Darwin dabbled in archaeology at the stones, experimenting with the rate at which remains sink into the earth for his book The Formation of Vegetable Mould Through the Action of Worms.

Stone 22 fell during a fierce storm on 31 December 1900.[112]

1901–2000

_-_1906.jpg.webp)

William Gowland oversaw the first major restoration of the monument in 1901, which involved the straightening and concrete setting of sarsen stone number 56 which was in danger of falling. In straightening the stone he moved it about half a metre from its original position.[110] Gowland also took the opportunity to further excavate the monument in what was the most scientific dig to date, revealing more about the erection of the stones than the previous 100 years of work had done. During the 1920 restoration William Hawley, who had excavated nearby Old Sarum, excavated the base of six stones and the outer ditch. He also located a bottle of port in the Slaughter Stone socket left by Cunnington, helped to rediscover Aubrey's pits inside the bank and located the concentric circular holes outside the Sarsen Circle called the Y and Z Holes.[113]

Richard Atkinson, Stuart Piggott and John F. S. Stone re-excavated much of Hawley's work in the 1940s and 1950s, and discovered the carved axes and daggers on the Sarsen Stones. Atkinson's work was instrumental in furthering the understanding of the three major phases of the monument's construction.

In 1958 the stones were restored again, when three of the standing sarsens were re-erected and set in concrete bases. The last restoration was carried out in 1963 after stone 23 of the Sarsen Circle fell over. It was again re-erected, and the opportunity was taken to concrete three more stones. Later archaeologists, including Christopher Chippindale of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge and Brian Edwards of the University of the West of England, campaigned to give the public more knowledge of the various restorations and in 2004 English Heritage included pictures of the work in progress in its book Stonehenge: A History in Photographs.[114][115][116]

In 1966 and 1967, in advance of a new car park being built at the site, the area of land immediately northwest of the stones was excavated by Faith and Lance Vatcher. They discovered the Mesolithic postholes dating from between 7000 and 8000 BC, as well as a 10-metre (33 ft) length of a palisade ditch – a V-cut ditch into which timber posts had been inserted that remained there until they rotted away. Subsequent aerial archaeology suggests that this ditch runs from the west to the north of Stonehenge, near the avenue.[113]

Excavations were once again carried out in 1978 by Atkinson and John Evans, during which they discovered the remains of the Stonehenge Archer in the outer ditch,[117] and in 1979 rescue archaeology was needed alongside the Heel Stone after a cable-laying ditch was mistakenly dug on the roadside, revealing a new stone hole next to the Heel Stone.

In the early 1980s Julian C. Richards led the Stonehenge Environs Project, a detailed study of the surrounding landscape. The project was able to successfully date such features as the Lesser Cursus, Coneybury Henge and several other smaller features.

In 1993 the way that Stonehenge was presented to the public was called 'a national disgrace' by the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee. Part of English Heritage's response to this criticism was to commission research to collate and bring together all the archaeological work conducted at the monument up to this date. This two-year research project resulted in the publication in 1995 of the monograph Stonehenge in its landscape, which was the first publication presenting the complex stratigraphy and the finds recovered from the site. It presented a rephasing of the monument.[118]

21st century

More recent excavations include a series of digs held between 2003 and 2008 known as the Stonehenge Riverside Project, led by Mike Parker Pearson. This project mainly investigated other monuments in the landscape and their relationship to the stones — notably, Durrington Walls, where another "Avenue" leading to the River Avon was discovered. The point where the Stonehenge Avenue meets the river was also excavated and revealed a previously unknown circular area which probably housed four further stones, most likely as a marker for the starting point of the avenue.

In April 2008, Tim Darvill of the University of Bournemouth and Geoff Wainwright of the Society of Antiquaries began another dig inside the stone circle to retrieve datable fragments of the original bluestone pillars. They were able to date the erection of some bluestones to 2300 BC,[3] although this may not reflect the earliest erection of stones at Stonehenge. They also discovered organic material from 7000 BC, which, along with the Mesolithic postholes, adds support for the site having been in use at least 4,000 years before Stonehenge was started. In August and September 2008, as part of the Riverside Project, Julian C. Richards and Mike Pitts excavated Aubrey Hole 7, removing the cremated remains from several Aubrey Holes that had been excavated by Hawley in the 1920s, and re-interred in 1935.[28] A licence for the removal of human remains at Stonehenge had been granted by the Ministry of Justice in May 2008, in accordance with the Statement on burial law and archaeology issued in May 2008. One of the conditions of the licence was that the remains should be reinterred within two years and that in the intervening period they should be kept safely, privately and decently.[119][120]

A new landscape investigation was conducted in April 2009. A shallow mound, rising to about 16 in (40 centimetres) was identified between stones 54 (inner circle) and 10 (outer circle), clearly separated from the natural slope. It has not been dated but speculation that it represents careless backfilling following earlier excavations seems disproved by its representation in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century illustrations. There is some evidence that, as an uncommon geological feature, it could have been deliberately incorporated into the monument at the outset.[25] A circular, shallow bank, little more than four inches (10 cm) high, was found between the Y and Z hole circles, with a further bank lying inside the "Z" circle. These are interpreted as the spread of spoil from the original Y and Z holes, or more speculatively as hedge banks from vegetation deliberately planted to screen the activities within.[25]

In 2010, the Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project discovered a "henge-like" monument less than 0.62 mi (1 km) away from the main site.[121] This new hengiform monument was subsequently revealed to be located "at the site of Amesbury 50", a round barrow in the Cursus Barrows group.[122]

In November 2011, archaeologists from University of Birmingham announced the discovery of evidence of two huge pits positioned within the Stonehenge Cursus pathway, aligned in celestial position towards midsummer sunrise and sunset when viewed from the Heel Stone.[123][124] The new discovery was made as part of the Stonehenge Hidden Landscape Project which began in the summer of 2010.[125] The project uses non-invasive geophysical imaging technique to reveal and visually recreate the landscape. According to team leader Vince Gaffney, this discovery may provide a direct link between the rituals and astronomical events to activities within the Cursus at Stonehenge.[124]

In December 2011, geologists from University of Leicester and the National Museum of Wales announced the discovery of the source of some of the rhyolite fragments found in the Stonehenge debitage. These fragments do not seem to match any of the standing stones or bluestone stumps. The researchers have identified the source as a 230-foot (70 m) long rock outcrop called Craig Rhos-y-felin (51°59′30″N 4°44′41″W / 51.99167°N 4.74472°W), near Pont Saeson in north Pembrokeshire, located 140 miles (220 km) from Stonehenge.[126][127]

In 2014, the University of Birmingham announced findings including evidence of adjacent stone and wooden structures and burial mounds near Durrington, overlooked previously, that may date as far back as 4000 BC.[128] An area extending to 4.6 square miles (12 km2) was studied to a depth of three metres with ground-penetrating radar equipment. As many as seventeen new monuments, revealed nearby, may be Late Neolithic monuments that resemble Stonehenge. The interpretation suggests a complex of numerous related monuments. Also included in the discovery is that the cursus track is terminated by two 16-foot (5 m) wide, extremely deep pits,[129] whose purpose is still a mystery.

An announcement in November 2020 stated that a plan to construct a four-lane tunnel for traffic below the site had been approved. This was intended to eliminate the section of the A303 that runs close to the circle. The plan had received opposition from a group of "archaeologists, environmentalists and modern-day druids" according to National Geographic but was supported by others who wanted to "restore the landscape to its original setting and improve the experience for visitors". Opponents of the plan were concerned that artifacts that are underground in the area would be lost or that excavation in the area could de-stabilize the stones, leading to their sinking, shifting or perhaps falling.[130][131]

In February 2021, archaeologists announced the discovery of "vast troves of Neolithic and Bronze Age artifacts"[131] while conducting excavations for the proposed highway tunnel near Stonehenge. The find included Bronze Age graves, late neolithic pottery and C-shaped enclosure on the intended site of the Stonehenge road tunnel. Remains also contained a shale object in one of the graves, burnt flint in C-shaped enclosure and the final resting place of a baby.[132]

In January 2022, archaeologists announced the discovery of thousands of prehistoric pits during an electromagnetic induction field survey around Stonehenge. Based on the shape of the pits and the artifacts found inside, the study's lead author, Philippe De Smedt, assumed that six of the 9 large pits excavated were made by prehistoric humans. One of the oldest was about 10000 years old and contained hunting tools.[133][134]

On 14 July 2023, the Department for Transport announced that, despite the original planning application having been overturned by the High Court in 2021, the Transport Secretary, Mark Harper, had approved plans for a 2 mi (3.2 km) road tunnel.[135]

Origin of sarsens and bluestones

In July 2020, a study led by David Nash of the University of Brighton concluded that the large sarsen stones were "a direct chemical match" to those found at West Woods near Marlborough, Wiltshire, some 15 miles (25 km) north of Stonehenge.[136] A core sample, originally extracted in 1958, had recently been returned. First the fifty-two sarsens were analysed using methods including x-ray fluorescence spectrometry to determine their chemical composition which revealed they were mostly similar. Then the core was destructively analysed and compared with stone samples from various locations in southern Britain. Fifty of the fifty-two megaliths were found to match sarsens in West Woods, thereby identifying the probable origin of the stones.[136][137][138]

During 2017 and 2018, excavations by professor Parker Pearson's team at Waun Mawn, a large stone circle site in the Preseli Hills, suggested that the site had originally housed a 110-metre (360 ft) diameter stone circle of the same size as Stonehenge's original bluestone circle, also orientated towards the midsummer solstice.[30][31] The circle at Waun Mawn also contained a hole from one stone which had a distinctive pentagonal shape, very closely matching the one pentagonal stone at Stonehenge (stonehole 91 at Waun Mawn / stone 62 at Stonehenge).[30][31] Soil dating of the sediments within the revealed stone holes, via optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), suggested the absent stones at Waun Mawn had been erected around 3400–3200 BC, and removed around 300–400 years later, a date consistent with theories that the same stones were moved and used at Stonehenge, before later being reorganised into their present locations and supplemented with local sarsens as was already understood.[30][31] Human activity at Waun Mawn ceased around the same time which has suggested that some people may have migrated to Stonehenge.[30][31] It has also been suggested that stones from other sources may have been added to Stonehenge, perhaps from other dismantled circles in the region.[30][31]

Further work in 2021 by Parker Pearson's team concluded that the Waun Mawn circle had never been completed, and of the stones which might once have stood at the site, no more than 13 had been removed in antiquity.[139][lower-alpha 5]

In popular culture

See also

Historical context

- Prehistoric Britain – Prehistoric human occupation of Britain

- Neolithic British Isles – British, Irish and Manx history c. 4100–2500 BC

- Bell Beaker culture – Archaeological culture, 2800–1800 BC

- Bronze Age Britain – Period of British history from c. 2500 until c. 800 BC

Other monuments in the Stonehenge ritual landscape

- Bluestonehenge – Prehistoric monument in Wiltshire, England

- Bush Barrow – Archaeological site in England

- Cuckoo Stone – Neolithic standing stone in Wiltshire, England

- Durrington Walls – Late Neolithic palisaded enclosure

- Normanton Down Barrows – Barrows in England

- Stonehenge Avenue – ancient avenue on Salisbury plain, Wiltshire, England

- Stonehenge Cursus – Neolithic monument in Wiltshire, England

- Woodhenge – Neolithic henge and timber circle monument near Stonehenge

About Stonehenge and replicas of Stonehenge

- Archaeoastronomy and Stonehenge – Stonehenge's use in tracking seasons

- Cultural depictions of Stonehenge

- Excavations at Stonehenge – Archaeological excavations at Stonehenge site

- Stonehenge replicas and derivatives – A list of non-ephemeral examples

- Stonehenge Free Festival – 1974–1984 UK music festival

- Stonehenge Landscape – Estate owned by the National Trust of England

Fiction

- Stonehenge, novel

Similar sites

- Stonehenge replicas and derivatives – A list of non-ephemeral examples

- Almendres Cromlech – Stone circle in Évora, Portugal

- Arkaim – Ancient settlement of the Sintashta culture

- Cahokia – Archaeological site near East St. Louis, Illinois, USA

- Carhenge – replica of Stonehenge near the city of Alliance, Nebraska

- Göbekli Tepe – Neolithic archaeological site in Turkey

- Goloring – ancient earthworks near Koblenz, Germany

- Goseck circle – Neolithic henge monument – Calendar circle built circa 4900 BC in Germany

- List of largest monoliths

- Maryhill Stonehenge – Stonehenge replica in Maryhill, Washington, U.S.

- Medicine wheel – Ancient stone circles in North America

- Nabta Playa – Calendar circle built circa 5000 BC in Egypt

- Newgrange – Neolithic monument in County Meath, Ireland

- Ring of Brodgar – A neolithic stone circle in Orkney, Scotland

- Carahunge – Prehistoric archaeological site in Armenia

Sites with similar sunrise or sunset alignments

- Manhattanhenge – Solar phenomenon in Manhattan, New York City

- MIThenge – Hallway at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Museums with collections from the World Heritage Site

- The Salisbury Museum – museum in Salisbury, England

- Wiltshire Museum – museum in Devizes, England

Footnotes

- ↑ "Whereas mtDNA lineages from megalith burials harbor haplogroups K, H, HV, V, U5b, T, and J (among others), males from megalith burials belong almost exclusively to YDNA haplogroup I, more specifically to the I2a sublineage, which has a time to most recent common ancestor of ~15000 BCE. This pattern of uniparental marker diversity is found not only among individuals buried in megaliths, but also in other farmer groups from the fourth millennium BCE, which display similar patterns of uniparental marker diversity ... The high frequency of the hunter-gatherer-derived I2a male lineages among megalith as well as nonmegalith individuals suggests a male sex-biased admixture process between the farmer and the hunter-gatherer groups. ... The I2 YDNA lineages that are very common among European Mesolithic hunter-gatherers are distinctly different from the YDNA lineages of the European Early Neolithic farmer groups, but frequent in the farmer groups of the fourth millennium BCE, suggesting a male hunter-gatherer admixture over time."[62]

- ↑ "... the predominance of a single Y haplogroup (I-M284) across the Irish and British Neolithic population. ... provides further evidence of the importance of patrilineal ancestry in these societies."[63]

- ↑ "Whereas mtDNA lineages from megalith burials harbor haplogroups K, H, HV, V, U5b, T, and J (among others), males from megalith burials belong almost exclusively to YDNA haplogroup I, more specifically to the I2a sublineage, which has a time to most recent common ancestor of ~15000 BCE. This pattern of uniparental marker diversity is found not only among individuals buried in megaliths, but also in other farmer groups from the fourth millennium BCE, which display similar patterns of uniparental marker diversity ... The high frequency of the hunter-gatherer-derived I2a male lineages among megalith as well as nonmegalith individuals suggests a male sex-biased admixture process between the farmer and the hunter-gatherer groups. ... The I2 YDNA lineages that are very common among European Mesolithic HGs are distinctly different from the YDNA lineages of the European Early Neolithic farmer groups, but frequent in the farmer groups of the fourth millennium BCE, suggesting a male hunter-gatherer admixture over time."[62]

- ↑ "We provide the first evidence for sex-biased admixture between hunter-gatherers and farmers in Europe, showing that the Middle Neolithic “resurgence” of hunter-gatherer-related ancestry in central Europe and Iberia was driven more by males than by females."[64]

- ↑ "In summary, the 2021 excavations provide evidence that only 30% of Waun Mawn's stone circle was ever completed, leaving large gaps on the west and south sides. [...] if Waun Mawn provided some of the bluestones for Stonehenge, these can only have been a small portion of the total."[139]

References

- 1 2 3 Historic England. "Stonehenge, the Avenue, and three barrows adjacent to the Avenue forming part of a round barrow cemetery on Countess Farm (1010140)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ↑ Young, Christopher; Chadburn, Amanda; Bedu, Isabelle (January 2009). "Stonehenge World Heritage Site Management Plan 2009" (PDF). UNESCO: 20–22.

- 1 2 Morgan, James (21 September 2008). "Dig pinpoints Stonehenge origins". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 September 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kennedy, Maev (9 March 2013). "Stonehenge may have been burial site for Stone Age elite, say archaeologists". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Legge, James (9 March 2012). "Stonehenge: new study suggests landmark started life as a graveyard for the 'prehistoric elite'". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- 1 2 "Stonehenge builders travelled from far, say researchers". BBC News. 9 March 2013. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ↑ Scott, Julie; Selwyn, Tom (2010). Thinking Through Tourism. Berg. p. 191.

- ↑ "History of Stonehenge". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

The monument remained in private ownership until 1918 when Cecil Chubb, a local man who had purchased Stonehenge from the Antrobus family at an auction three years previously, gave it to the nation. Thereafter, the duty to conserve the monument fell to the state, today a role performed on its behalf by English Heritage.

- ↑ "Ancient ceremonial landscape of great archaeological and wildlife interest". Stonehenge Landscape. National Trust. Archived from the original on 18 June 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ↑ Pitts, Mike (8 August 2008). "Stonehenge: one of our largest excavations draws to a close". British Archaeology (102): 13. ISSN 1357-4442.

- 1 2 Schmid, Randolph E. (29 May 2008). "Study: Stonehenge was a burial site for centuries". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Stonehenge; henge2". Oxford English Dictionary (2 ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1989.

- ↑ Chippindale, C (2004), Stonehenge Complete, London: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-28467-9

- ↑ See the English Heritage definition Archived 16 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Anon. "Stonehenge : Wiltshire England What is it?". Megalithic Europe. The Bradshaw Foundation. Archived from the original on 30 May 2009. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ↑ Alexander, Caroline. "If the Stones Could Speak: Searching for the Meaning of Stonehenge". National Geographic Magazine. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 28 September 2009. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ↑ Exon, 30-31; Southern, Patricia, The Story of Stonehenge, Ch. 2 Archived 7 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine, 2012, Amberley Publishing Limited, ISBN 1-4456-1587-8, 978-1-4456-1587-5

- ↑ V. Gaffney; et al. "Time and a Place: A luni-solar 'time-reckoner' from 8th millennium BC Scotland". Internet Archaeology. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ Exon, 30

- 1 2 "The New Discoveries at Blick Mead: the Key to the Stonehenge Landscape". University of Buckingham. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ↑ Professor David Jacques FSA (21 September 2016). "'The Cradle of Stonehenge'? Blick Mead – a Mesolithic Site in the Stonehenge Landscape – Lecture Transcript". www.gresham.ac.uk. Gresham College. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ↑ Webb, John (1665). Stone-Henge Restored with Observations on Rules of Architecture. London: Tho. Bassett. p. 17. OCLC 650116061.

- ↑ Charlton, Dr. Walter (1715). The Chorea Gigantum, Or, Stone-Heng Restored to the Danes. London: James Bettenham. p. 45. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ↑ Sarah Knapton (19 December 2014). "Stonehenge discovery could rewrite British pre-history". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 Field, David; et al. (March 2010). "Introducing 'Stonehedge'". British Archaeology (111): 32–35. ISSN 1357-4442.

- ↑ Cleal et al, 1996. Antiquity, 1996 Jun, Vol.70(268), pp.463-465

- ↑ Parker Pearson, Mike; Richards, Julian; Pitts, Mike (9 October 2008). "Stonehenge 'older than believed'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- 1 2 Mike Parker Pearson (20 August 2008). "The Stonehenge Riverside Project". Sheffield University. Archived from the original on 26 October 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ↑ Christophe Snoeck; et al. (2 August 2018). "Strontium isotope analysis on cremated human remains from Stonehenge support links with west Wales". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 10790. Bibcode:2018NatSR...810790S. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-28969-8. PMC 6072783. PMID 30072719.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Pearson, Mike Parker; Pollard, Josh; Richards, Colin; Welham, Kate; Kinnaird, Timothy; Shaw, Dave; et al. (12 February 2021). "The original Stonehenge? A dismantled stone circle in the Preseli Hills of west Wales". Antiquity. 95 (379): 85–103. doi:10.15184/aqy.2020.239.

Waun Mawn is the third largest of Britain's great stone circles with diameters over 100 m.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Curry, Andrew (11 February 2021). "England's Stonehenge was erected in Wales first". Science. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- 1 2 Burns, William E. (2020). Science and Technology in World History. ABC-CLIO. p. 100.

- ↑ John, Brian (26 February 2011). "Stonehenge: glacial transport of bluestones now confirmed?" (PDF) (Press release). University of Leicester. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Parker Pearson, Michael; et al. (December 2015). "Craig Rhos-y-felin: a Welsh bluestone megalith quarry for Stonehenge". Antiquity. 89 (348): 1331–1352. doi:10.15184/aqy.2015.177.

- ↑ Pearson, Mike Parker; Pollard, Josh; Richards, Colin; Welham, Kate; Casswell, Chris; French, Charles; Schlee, Duncan; Shaw, Dave; Simmons, Ellen; Stanford, Adam; Bevins, Richard; Ixer, Rob (2019). "Megalith quarries for Stonehenge's bluestones". Antiquity. 93 (367): 45–62. doi:10.15184/aqy.2018.111. S2CID 166415345.

- ↑ Alberge, Dalya (12 February 2021). "Dramatic discovery links Stonehenge to its original site – in Wales". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- 1 2 Nash, David; Ciborowski, T. Jake R.; Ullyott, J. Stewart; Pearson, Mick Parker (29 July 2020). "Origins of the sarsen megaliths at Stonehenge". Science Advances. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 5 (31): eabc0133. Bibcode:2020SciA....6..133N. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abc0133. PMC 7439454. PMID 32832694. S2CID 220937543.

- ↑ Banton, Simon; Bowden, Mark; Daw, Tim; Grady, Damian; Soutar, Sharon (July 2013). "Patchmarks at Stonehenge". Antiquity. 88 (341): 733–739. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00050651. S2CID 162412146.

- ↑ Pearson, Mike; Cleal, Ros; Marshall, Peter; Needham, Stuart; Pollard, Josh; Richards, Colin; et al. (September 2007). "The age of Stonehenge" (PDF). Antiquity. 811 (313): 617–639. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00095624. S2CID 162960418. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- 1 2 Pearson, M. Parker (2005). Bronze Age Britain. B.T. Batsford. pp. 63–67. ISBN 978-0-7134-8849-4.

- ↑ "Skeleton unearthed at Stonehenge was decapitated" Archived 30 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (9 June 2000), ABCE News (13 June 2000), Fox News (14 June 2000), New Scientist (17 June 2000), Archeo News (2 July 2000)

- ↑ "Research on Stonehenge". English Heritage. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- 1 2 "Stonehenge a monument to unity, new theory claims – CBS News". CBS News. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

- ↑ "Understanding Stonehenge: Two Explanations". DNews. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ↑ Schombert. "Stonehenge revealed: Why Stones Were a "Special Place"". University of Oregon. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ↑ Alberge, Dalya (8 September 2013). "Stonehenge was built on solstice axis, dig confirms". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ Pearson (22 June 2013). "Stonehenge". Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ↑ John Coles (2014), Archaeology by Experiment, Routledge, pp. 76–77, ISBN 9781317606086

- 1 2 3 "Stonehenge". Gale Encyclopedia of the Unusual and Unexplained. US: Gale. 2003. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- 1 2 Hawkins, GS (1966). Stonehenge Decoded. ISBN 978-0-88029-147-7.

- ↑ Satter, Raphael (27 September 2008). "UK experts say Stonehenge was place of healing". USA Today. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ↑ Maev Kennedy (23 September 2008). "The magic of Stonehenge: new dig finds clues to power of bluestones". Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ "Stonehenge boy 'was from the Med'". BBC News. 28 September 2010. Archived from the original on 29 September 2010. Retrieved 28 August 2010.

- ↑ Williams, Thomas; Koriech, Hana (2012). "Interview with Mike Parker Pearson". Papers from the Institute of Archaeology. 22: 39–47. doi:10.5334/pia.401.

- ↑ "RCA Research Team Uncovers Stonehenge's Sonic Secrets". Royal College of Art. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ↑ Curry, Andrew (August 2019). "The first Europeans weren't who you might think". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021.

- 1 2 Paul Rincon, Stonehenge: DNA reveals origin of builders. Archived 5 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine BBC News website, 16 April 2019

- 1 2 3 Brace, Selina; Diekmann, Yoan; Booth, Thomas J.; van Dorp, Lucy; Faltyskova, Zuzana; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Olalde, Iñigo; Ferry, Matthew; Michel, Megan; Oppenheimer, Jonas; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Stewardson, Kristin; Martiniano, Rui; Walsh, Susan; Kayser, Manfred; Charlton, Sophy; Hellenthal, Garrett; Armit, Ian; Schulting, Rick; Craig, Oliver E.; Sheridan, Alison; Parker Pearson, Mike; Stringer, Chris; Reich, David; Thomas, Mark G.; Barnes, Ian (2019). "Ancient genomes indicate population replacement in Early Neolithic Britain". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (5): 765–771. Bibcode:2019NatEE...3..765B. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0871-9. ISSN 2397-334X. PMC 6520225. PMID 30988490.

- ↑ Patterson, Nick; et al. (2022). "Large-Scale Migration into Britain During the Middle to Late Bronze Age". Nature. 601 (7894): 588–594. Bibcode:2022Natur.601..588P. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04287-4. PMC 8889665. PMID 34937049.

Whole genome ancient DNA studies have shown that the first Neolithic farmers of the island of Great Britain who lived 3950–2450 BCE derived roughly 80% of their ancestry from Early European Farmers (EEF) who originated in Anatolia more than two millennia earlier, and 20% from Mesolithic hunter-gatherers (Western European Hunter-Gatherers: WHG) with whom they mixed in continental Europe, indicating that local WHG in Britain contributed negligibly to later populations.

- 1 2 McNish, James (22 February 2018). "The Beaker people: a new population for ancient Britain". Natural History Museum.

- ↑ Olalde, Inigo (2018). "The Beaker Phenomenon and the Genomic Transformation of Northwest Europe". Nature. 555 (7695): 190–196. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..190O. doi:10.1038/nature25738. PMC 5973796. PMID 29466337.

Another striking observation is the haplogroup composition of Neolithic males in Britain (n=34), who displayed entirely I2a2 and I2a1b haplogroups. There is no evidence at all for a contribution to Neolithic farmers in Britain of the Y chromosome haplogroups (e.g., G2) that were predominant in Anatolian farmers and in Linearbandkeramik central European farmers.

- 1 2 3 Sánchez-Quinto, Federico (2019). "Megalithic tombs in western and northern Neolithic Europe were linked to a kindred society". PNAS. 116 (19): 9469–9474. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.9469S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1818037116. PMC 6511028. PMID 30988179.

- 1 2 Cassidy, Lara (2020). "A dynastic elite in monumental Neolithic society". Nature. 582 (7812): 384–388. Bibcode:2020Natur.582..384C. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2378-6. PMC 7116870. PMID 32555485.

- 1 2 Mathieson, Ian (2018). "The genomic history of south eastern Europe". Nature. 555 (7695): 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- ↑ Needham, S. (2005). "Transforming Beaker Culture in North-West Europe: processes of fusion and fission". Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. 71: 171–217. doi:10.1017/s0079497x00001006. S2CID 193226917.

- ↑ Barras, Colin (27 March 2019). "Story of most murderous people of all time revealed in ancient DNA". New Scientist.

- ↑ The Beaker Phenomenon And The Genomic Transformation Of Northwest Europe (2017)

- ↑ Bianca Preda (6 May 2020). "Yamnaya - Corded Ware - Bell Beakers: How to conceptualise events of 5000 years ago". The Yamnaya Impact On Prehistoric Europe. University of Helsinki.

- ↑ Barry W. Cunliffe, The Oxford Illustrated History of Prehistoric Europe. Archived 12 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine Oxford University Press, 2001. p.254

- ↑ Dr Andrew Fitzpatrick, Wessex Culture-an elitist subgroup? Archived 25 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine Wessex Archaeology, December 2012

- ↑ Bradley, Richard (2007). The prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84811-4. p.146

- ↑ Stevens, Chris; Fuller, Dorian (2015). "Did Neolithic farming fail? The case for a Bronze Age agricultural revolution in the British Isles". Antiquity. 86 (333): 707–722. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00047864. S2CID 162740064.

- 1 2 Stanford, Peter (2011). The Extra Mile: A 21st century Pilgrimage. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 20.

- ↑ Stevens, Edward (July 1866). "Stonehenge and Abury". The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Review. Vol. 11. London: Bradbury, Evans & Co. p. 69. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Measuring Time: Teacher's Guide. Burlington, NC: National Academy of Sciences. 1994. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-89278-707-4. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Andrew Oliver, ed. (1972). "July 1776". The Journal of Samuel Curwen, loyalist. Vol. 1. Harvard University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-674-48380-4. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ "Jeffery of Monmouth's Account of Stonehenge". A Description of Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. Salisbury: J Easton. 1809. p. 5. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Brewer, Ebenezer Cobham. Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. New York: Harper and Brothers. p. 380. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Warne, Charles, 1872, Ancient Dorset. Bournemouth.

- ↑ Historia Regum Britanniae, Book 8, ch. 10.

- ↑ Ring, Trudy (editor). International Dictionary of Historic Places, Volume 2: Northern Europe. Routledge, 1995. pp.34-35

- ↑ Dames, Michael. Ireland: A Sacred Journey. Element Books, 2000. p.190