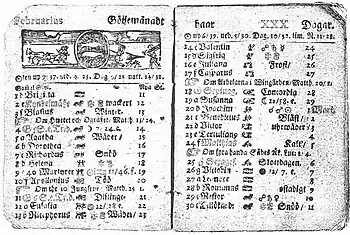

The Swedish calendar (Swedish: svenska kalendern) or Swedish style (svenska stilen) was a calendar in use in Sweden and its possessions from 1 March 1700 until 30 February 1712 (see below). It was one day ahead of the Julian calendar and ten days behind the Gregorian calendar. Easter was calculated astronomically, with a minor exception, from 1740 to 1844.

Solar calendar

In November 1699, the Government of Sweden decided that, rather than adopt the Gregorian calendar outright, it would gradually approach it over a 40-year period. The plan was to skip all leap days in the period 1700 to 1740. Every fourth year, the gap between the Swedish calendar and the Gregorian would reduce by one day, until they finally lined up in 1740. In the meantime, this calendar would not be in line with either of the major alternative calendars and the differences would change every four years.

In accordance with the plan, 29 February was omitted in 1700, but the Great Northern War stopped any further omissions from being made in the following years.

In January 1711, King Charles XII declared that Sweden would abandon the calendar, which was not in use by any other nation, in favour of a return to the older Julian calendar. An extra day was added to February in the leap year of 1712, thus giving the month a unique 30-day (30 February) and the year a 367-day length.

In 1753, one year later than England and its colonies, Sweden introduced the Gregorian calendar. The leap of 11 days was accomplished in one step, with 17 February being followed by 1 March.[1]

Easter

Easter was to be calculated according to the Easter rules of the Julian calendar from 1700 until 1739, but from 1700 to 1711, Easter Sunday was dated in the anomalous Swedish calendar, described above.

In 1740, Sweden finally adopted the "improved calendar" already adopted by the Protestant states of Germany in 1700 (which they used until 1775). Its improvement was to calculate the full moon and vernal equinox of Easter according to astronomical tables, specifically Kepler's Rudolphine Tables at the meridian of Tycho Brahe's Uraniborg observatory (destroyed long before) on the former Danish island of Hven near the southern tip of Sweden.[2][3] In addition to the usual medieval rule that Easter was the first Sunday after the first full moon after the vernal equinox, the astronomical Easter Sunday was to be delayed by one week if this calculation would have placed it on the same day as the first day of Jewish Passover week, Nisan 15. It conflicts with the Julian Easter, which could not occur on the 14th day of the moon (Nisan 14), but was permitted on Nisan 15 to 21 although those dates were calculated via Christian, not Jewish, tables (see Computus). The resulting astronomical Easter dates in the Julian calendar used in Sweden from 1740 to 1752 occurred on the same Sunday as the Julian Easter every three years but were earlier than the earliest canonical limit for Easter of 22 March in 1742, 1744 and 1750.

After the adoption of the Gregorian solar calendar in 1753, three astronomical Easter dates were one week later than the Gregorian Easter in 1802, 1805 and 1818. Before Sweden formally adopted the Gregorian Easter in 1844, two more should have been delayed in 1825 and 1829 but were not.

Finland was part of Sweden until 1809 when it became the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland within the Russian Empire due to the Finnish War. Until 1866, Finland continued to observe the astronomical Easter, which was one week after the Gregorian Easter in 1818, 1825, 1829 and 1845. However, Russia then used the Julian calendar and Julian Easter so the comparison given above applies: that the astronomical Easter agreed with the Julian Easter about every third year but was sometimes earlier than 22 March in the Julian calendar.

See also

References

- ↑ Roscoe Lamont, The reform of the Julian calendar (II), Popular Astronomy 28 (1920) 18–32, see pages 24–25.

- ↑ Anomalous Easter Sunday Dates during the 18th and early 19th Century by Robert van Gent

- ↑ Anomalous Easter Sunday Dates in Sweden and Finland by Robert van Gent