In computer science and computer programming, system time represents a computer system's notion of the passage of time. In this sense, time also includes the passing of days on the calendar.

System time is measured by a system clock, which is typically implemented as a simple count of the number of ticks that have transpired since some arbitrary starting date, called the epoch. For example, Unix and POSIX-compliant systems encode system time ("Unix time") as the number of seconds elapsed since the start of the Unix epoch at 1 January 1970 00:00:00 UT, with exceptions for leap seconds. Systems that implement the 32-bit and 64-bit versions of the Windows API, such as Windows 9x and Windows NT, provide the system time as both SYSTEMTIME, represented as a year/month/day/hour/minute/second/milliseconds value, and FILETIME, represented as a count of the number of 100-nanosecond ticks since 1 January 1601 00:00:00 UT as reckoned in the proleptic Gregorian calendar.

System time can be converted into calendar time, which is a form more suitable for human comprehension. For example, the Unix system time 1000000000 seconds since the beginning of the epoch translates into the calendar time 9 September 2001 01:46:40 UT. Library subroutines that handle such conversions may also deal with adjustments for time zones, daylight saving time (DST), leap seconds, and the user's locale settings. Library routines are also generally provided that convert calendar times into system times.

Many implementations that currently store system times as 32-bit integer values will suffer from the impending Year 2038 problem. These time values will overflow ("run out of bits") after the end of their system time epoch, leading to software and hardware errors. These systems will require some form of remediation, similar to efforts required to solve the earlier Year 2000 problem. This will also be a potentially much larger problem for existing data file formats that contain system timestamps stored as 32-bit values.

Other time measurements

Closely related to system time is process time, which is a count of the total CPU time consumed by an executing process. It may be split into user and system CPU time, representing the time spent executing user code and system kernel code, respectively. Process times are a tally of CPU instructions or clock cycles and generally have no direct correlation to wall time.

File systems keep track of the times that files are created, modified, and/or accessed by storing timestamps in the file control block (or inode) of each file and directory.

History

Most first-generation personal computers did not keep track of dates and times. These included systems that ran the CP/M operating system, as well as early models of the Apple II, the BBC Micro, and the Commodore PET, among others. Add-on peripheral boards that included real-time clock chips with on-board battery back-up were available for the IBM PC and XT, but the IBM AT was the first widely available PC that came equipped with date/time hardware built into the motherboard. Prior to the widespread availability of computer networks, most personal computer systems that did track system time did so only with respect to local time and did not make allowances for different time zones.

With current technology, most modern computers keep track of local civil time, as do many other household and personal devices such as VCRs, DVRs, cable TV receivers, PDAs, pagers, cell phones, fax machines, telephone answering machines, cameras, camcorders, central air conditioners, and microwave ovens.

Microcontrollers operating within embedded systems (such as the Raspberry Pi, Arduino, and other similar systems) do not always have internal hardware to keep track of time. Many such controller systems operate without knowledge of the external time. Those that require such information typically initialize their base time upon rebooting by obtaining the current time from an external source, such as from a time server or external clock, or by prompting the user to manually enter the current time.

Implementation

The system clock is typically implemented as a programmable interval timer that periodically interrupts the CPU, which then starts executing a timer interrupt service routine. This routine typically adds one tick to the system clock (a simple counter) and handles other periodic housekeeping tasks (preemption, etc.) before returning to the task the CPU was executing before the interruption.

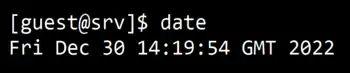

Retrieving system time

The following tables illustrate methods for retrieving the system time in various operating systems, programming languages, and applications. Values marked by (*) are system-dependent and may differ across implementations. All dates are given as Gregorian or proleptic Gregorian calendar dates.

The resolution of an implementation's measurement of time does not imply the same precision of such measurements. For example, a system might return the current time as a value measured in microseconds, but actually be capable of discerning individual clock ticks with a frequency of only 100 Hz (10 ms).

Operating systems

| Operating system | Command or function | Resolution | Epoch or range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Android | java.lang.System.currentTimeMillis() |

1 ms | 1 January 1970 |

| BIOS (IBM PC) | INT 1Ah, AH=00h[1] |

54.9254 ms 18.2065 Hz |

Midnight of the current day |

INT 1Ah, AH=02h[2] |

1 s | Midnight of the current day | |

INT 1Ah, AH=04h[3] |

1 day | 1 January 1980 to 31 December 1999 or 31 December 2079 (system dependent) | |

| CP/M Plus | System Control Block:[4]scb$base+58h, Days since 31 December 1977scb$base+5Ah, Hour (BCD)scb$base+5Bh, Minute (BCD)scb$base+5Ch, Second (BCD) |

1 s | 31 December 1977 to 5 June 2157 |

BDOS function 69h> (T_GET):[5]word, Days since 1 January 1978byte, Hour (BCD)byte, Minute (BCD)byte, Second (BCD) | |||

| DOS (Microsoft) | C:\> DATEC:\> TIME |

10 ms | 1 January 1980 to 31 December 2099 |

INT 21h, AH=2Ch SYSTEM TIME[6]INT 21h, AH=2Ah SYSTEM DATE[7] | |||

| iOS (Apple) | CFAbsoluteTimeGetCurrent()[8] |

< 1 ms | 1 January 2001 ±10,000 years |

| macOS | CFAbsoluteTimeGetCurrent()[9] |

< 1 ms[10][note 1] | 1 January 2001 ±10,000 years[10][note 1] |

| OpenVMS | SYS$GETTIM() |

100 ns[11] | 17 November 1858 to 31 July 31,086[12] |

| () | 1 μs[13] | 1 January 1970 to 7 February 2106[14] | |

| () | 1 ns[13] | ||

| z/OS | STCK[15]: 7–187 |

2−12 μs 244.14 ps[15]: 4–45, 4–46 |

1 January 1900 to 17 September 2042 UT[16] |

STCKE |

1 January 1900 to AD 36,765[17] | ||

| Unix, POSIX (see also C date and time functions) |

$datetime() |

1 s | (*) 1 January 1970 (to 19 January 2038 prior to Linux 5.9) to 2 July 2486 (Since Linux 5.10) 1 January 1970 to 4 December AD 292,277,026,596 |

| () | 1 μs | ||

| () | 1 ns | ||

| OS/2 | DosGetDateTime() |

10 ms | 1 January 1980 to 31 December 2079[18] |

| Windows | GetSystemTime() |

1 ms | 1 January 1601 to 14 September 30828, 02:48:05.4775807 |

GetSystemTimeAsFileTime() |

100 ns | ||

GetSystemTimePreciseAsFileTime() |

Programming languages and applications

| Language/Application | Function or variable | Resolution | Epoch or range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ada | Ada.Calendar.Clock |

100 μs to 20 ms (*) |

1 January 1901 to 31 December 2099 (*) |

| AWK | systime() |

1 s | (*) |

| BASIC, True BASIC | DATE, DATE$TIME, TIME$ |

1 s | (*) |

| Business BASIC | DAY, TIM |

0.1 s | (*) |

| C (see C date and time functions) | time() |

1 s (*)[note 2] | (*)[note 2] |

| C++ | std::time() std::chrono::system_clock::now() |

1 s (*)[note 2] 1 ns (C++11, OS dependent) |

(*)[note 2] |

| C# | System.DateTime.Now[19]System.DateTime.UtcNow[20] |

100 ns[21] | 1 January 0001 to 31 December 9999 |

| CICS | ASKTIME |

1 ms | 1 January 1900 |

| COBOL | FUNCTION CURRENT-DATE |

1 s | 1 January 1601 |

| Common Lisp | (get-universal-time) |

1 s | 1 January 1900 |

| Delphi (Borland) | datetime |

1 ms (floating point) |

1 January 1900 |

| Delphi (Embarcadero Technologies)[22] |

System.SysUtils.Time[23] |

1 ms | 0/0/0000 0:0:0:000 to 12/31/9999 23:59:59:999 [sic] |

System.SysUtils.GetTime[24] (alias for System.SysUtils.Time) | |||

System.SysUtils.Date[25] |

0/0/0000 0:0:0:000 to 12/31/9999 0:0:0:000 [sic] | ||

System.DateUtils.Today[26] | |||

System.DateUtils.Tomorrow[27] | |||

System.DateUtils.Yesterday[28] | |||

System.SysUtils.Now[29] |

1 s | 0/0/0000 0:0:0:000 to 12/31/9999 23:59:59:000 [sic] | |

System.SysUtils.DayOfWeek[30] |

1 day | 1 to 7 | |

System.SysUtils.CurrentYear[31] |

1 year | (*) | |

| Emacs Lisp | (current-time) |

1 μs (*) | 1 January 1970 |

| Erlang | erlang:system_time(), os:system_time()[32] |

OS dependent, e.g. on Linux 1ns[32] | 1 January 1970[32] |

| Excel | date() |

? | 0 January 1900[33] |

| Fortran | DATE_AND_TIMESYSTEM_CLOCK |

(*)[34] | 1 January 1970 |

CPU_TIME |

1 μs | ||

| Go | time.Now() |

1 ns | 1 January 0001 |

| Haskell | Time.getClockTime |

1 ps (*) | 1 January 1970 (*) |

Data.Time.getCurrentTime |

1 ps (*) | 17 November 1858 (*) | |

| Java | java.util.Date()System.currentTimeMillis() |

1 ms | 1 January 1970 |

System.nanoTime()[36] |

1 ns | arbitrary[36] | |

Clock.systemUTC()[37] |

1 ns | arbitrary[38] | |

| JavaScript, TypeScript | (new Date()).getTime()Date.now() |

1 ms | 1 January 1970 |

| Matlab | now |

1 s | 0 January 0000[39] |

| MUMPS | $H (short for [[Horology|$HOROLOG]]) |

1 s | 31 December 1840 |

| LabVIEW | Tick Count |

1 ms | 00:00:00.000 1 January 1904 |

Get Date/Time in Seconds |

1 ms | 00:00:00.000 1 January 1904 | |

| Objective-C | [NSDate timeIntervalSinceReferenceDate] |

< 1 ms[40] | 1 January 2001 ±10,000 Years[40] |

| OCaml | Unix.time() |

1 s | 1 January 1970 |

Unix.gettimeofday() |

1 μs | ||

| Extended Pascal | GetTimeStamp() |

1 s | (*) |

| Turbo Pascal | GetTime()GetDate() |

10 ms | (*) |

| Perl | time() |

1 s | 1 January 1970 |

Time::HiRes::time[41] |

1 μs | ||

| PHP | time()mktime() |

1 s | 1 January 1970 |

microtime() |

1 μs | ||

| PureBasic | Date() |

1 s | 1 January 1970 to 19 January 2038 |

| Python | datetime.now().timestamp() |

1 μs (*) | 1 January 1970 |

| RPG | CURRENT(DATE), %DATECURRENT(TIME), %TIME |

1 s | 1 January 0001 to 31 December 9999 |

CURRENT(TIMESTAMP), %TIMESTAMP |

1 μs | ||

| Ruby | Time.now()[42] |

1 μs (*) | 1 January 1970 (to 19 January 2038 prior to Ruby 1.9.2[43]) |

| Scheme | (get-universal-time)[44] |

1 s | 1 January 1900 |

| Smalltalk | Time microsecondClock(VisualWorks) |

1 s (ANSI) 1 μs (VisualWorks) 1 s (Squeak) |

1 January 1901 (*) |

Time totalSeconds(Squeak) | |||

SystemClock ticksNowSinceSystemClockEpoch(Chronos) | |||

| SQL | CURDATE() or CURRENT DATECURTIME() or CURRENT TIMEGETDATE() or GETUTCDATE()NOW() or CURRENT TIMESTAMPSYSDATE() |

3 ms | 1 January 1753 to 31 December 9999 (*) |

| 60 s | 1 January 1900 to 6 June 2079 | ||

| Standard ML | Time.now() |

1 μs (*) | 1 January 1970 (*) |

| TCL | [clock seconds] |

1 s | 1 January 1970 |

[clock milliseconds] |

1 ms | ||

[clock microseconds] |

1 μs | ||

[clock clicks] |

1 μs (*) | (*) | |

| Windows PowerShell | Get-Date[45][46] |

100 ns[21] | 1 January 0001 to 31 December 9999 |

[DateTime]::Now[19][DateTime]::UtcNow[20] | |||

| Visual Basic .NET | System.DateTime.Now[19]System.DateTime.UtcNow[20] |

100 ns[21] | 1 January 0001 to 31 December 9999 |

See also

Notes

- 1 2 The Apple Developer Documentation is not clear on the precision & range of CFAbsoluteTime/CFTimeInterval, except in the CFRunLoopTimerCreate documentation which refers to 'sub-millisecond at most' precision. However, the similar type NSTimeInterval appears to be interchangeable, and has the precision and range listed.

- 1 2 3 4 The C standard library does not specify any specific resolution, epoch, range, or datatype for system time values. The C++ library encompasses the C library, so it uses the same system time implementation as C.

References

- ↑ Ralf D. Brown (2000). "Int 0x1A, AH=0x00". Ralf Brown's Interrupt List.

- ↑ Ralf D. Brown (2000). "Int 0x1A, AH=0x02". Ralf Brown's Interrupt List.

- ↑ Ralf D. Brown (2000). "Int 0x1A, AH=0x04". Ralf Brown's Interrupt List.

- ↑ "CP/M Plus (CP/M Version 3.0) Operating System Guide" (PDF).

- ↑ "BDOS system calls".

- ↑ Ralf D. Brown (2000). "Int 0x21, AH=0x2c". Ralf Brown's Interrupt List.

- ↑ Ralf D. Brown (2000). "Int 0x21, AH=0x2a". Ralf Brown's Interrupt List.

- ↑ "Time Utilities Reference". iOS Developer Library. 2007.

- ↑ "Time Utilities Reference". Mac OS X Developer Library. 2007.

- 1 2 "Time Utilities - Foundation". Apple Developer Documentation. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ↑ Ruth E. Goldenberg; Lawrence J. Kenah; Denise E. Dumas (1991). VAX/VMS Internals and Data Structures, Version 5.2. Digital Press. ISBN 978-1555580599.

- ↑ "Why is Wednesday, November 17, 1858 the base time for OpenVMS (VAX VMS)?". Stanford University. 24 July 1997. Archived from the original on 24 July 1997. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- 1 2 "VSI C Run-Time Library Reference Manual for OpenVMS Systems" (PDF). VSI. November 2020. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ↑ "OpenVMS and the year 2038". HP. Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- 1 2 z/Architecture Principles of Operation (PDF). Poughkeepsie, New York: International Business Machines. 2007.

- ↑ IBM intends to extend the date range on future systems beyond 2042. z/Architecture Principles of Operation, (Poughkeepsie, New York:International Business Machines, 2007) 1-15, 4-45 to 4-47.

- ↑ "Expanded 64-bit time values". IBM. Retrieved 2021-04-18.

- ↑ Jonathan de Boyne Pollard. "The 32-bit Command Interpreter".

On OS/2 Warp 4, date and time can both operate well beyond the year 2000, and even well beyond the year 2038, and in fact up to the year 2079, which is the limit for OS/2 Warp 4's real-time clock.

- 1 2 3 "DateTime.Now Property". Microsoft Docs.

- 1 2 3 "DateTime.UtcNow Property". Microsoft Docs.

- 1 2 3 "DateTime.Ticks Property". Microsoft Docs.

- ↑ "Date and Time Support". Embarcadero Developer Network. 2013.

- ↑ "System.SysUtils.Time". Embarcadero Developer Network. 2013.

- ↑ "System.SysUtils.GetTime". Embarcadero Developer Network. 2013.

- ↑ "System.SysUtils.Date". Embarcadero Developer Network'. 2013.

- ↑ "System.DateUtils.Today". Embarcadero Developer Network. 2013.

- ↑ "System.DateUtils.Tomorrow". Embarcadero Developer Network. 2013.

- ↑ "System.DateUtils.Yesterday". Embarcadero Developer Network. 2013.

- ↑ "System.SysUtils.Now". Embarcadero Developer Network. 2013.

- ↑ "System.SysUtils.DayOfWeek". Embarcadero Developer Network. 2013.

- ↑ "System.SysUtils.CurrentYear". Embarcadero Developer Network. 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Time and Time Correction in Erlang". www.erlang.org.

- ↑ "XL2000: Early Dates on Office Spreadsheet Component Differ from Excel". Microsoft Support. 2003. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007.

In the Microsoft Office Spreadsheet Component, the value 0 evaluates to the date December 30, 1899 and the value 1 evaluates to December 31, 1899. ... In Excel, the value 0 evaluates to January 0, 1900 and the value 1 evaluates to January 1, 1900.

- ↑ "SYSTEM_CLOCK". Intel Fortran Compiler 19.0 Developer Guide and Reference. 29 April 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ↑ "SYSTEM_CLOCK — Time function". The GNU Fortran Compiler. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- 1 2 "System.nanoTime() method". Java Platform, Standard Edition 6: API Specification. 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ↑ "Clock.systemUTC() and other methods". Java Platform, Standard Edition 8: API Specification. 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "JSR-310 Java Time System". Java Platform, Standard Edition 8: API Specification. 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "Matlab Help".

- 1 2 "NSTimeInterval - Foundation". Apple Developer Documentation.

- ↑ Douglas Wegscheild, R. Schertler, and Jarkko Hietaniemi, "Time::HiRes". CPAN - Comprehensive Perl Archive Network. 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ James Britt; Neurogami. "Time class". Ruby-Doc.org: Help and documentation for the Ruby programming language. Scottsdale, AZ. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ Yugui (18 August 2010). "Ruby 1.9.2 is released".

The new 1.9.2 is almost compatible with 1.9.1, except these changes: ... Time is reimplemented. The bug with year 2038 is fixed.

- ↑ "MIT/GNU Scheme 9.2: 15.5 Date and Time".

- ↑ "Using the Get-Date Cmdlet". Microsoft Docs. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ↑ "Windows PowerShell Tip of the Week – Formatting Dates and Times". Microsoft Docs. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

External links

- Critical and Significant Dates, J. R. Stockton (retrieved 3 December 2015)

- The Boost Date/Time Library (C++)

- The Boost Chrono Library (C++)

- The Chronos Date/Time Library (Smalltalk)

- Joda Time, The Joda Date/Time Library (Java)

- The Perl DateTime Project Archived 2009-02-19 at the Wayback Machine (Perl)

- date: Ruby Standard Library Documentation (Ruby)

.png.webp)