| Tetris | |

|---|---|

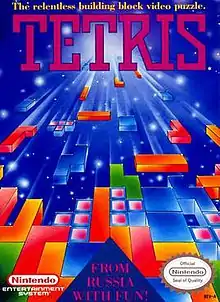

North American box art | |

| Developer(s) | Nintendo R&D1 |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Producer(s) | Gunpei Yokoi |

| Composer(s) | Hirokazu Tanaka |

| Series | Tetris |

| Platform(s) | Nintendo Entertainment System |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Puzzle |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Tetris or classic Tetris is a puzzle video game for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) released in 1989, based on Tetris (1985[1]) by Alexey Pajitnov. It is the first official console release of Tetris to have been developed and published by Nintendo. It was preceded by an official Tetris for the Family Computer in Japan in December 1988,[2] and an unofficial Tetris by Tengen in North America in May 1989.

Gameplay

This version of Tetris has two modes of play: A-Type and B-Type. In A-Type play, the goal is to achieve the highest score. As lines are cleared, the level advances and increases the speed of the falling blocks. At the beginning of a B-Type game, the board starts with randomized obstacle blocks at the bottom of the field, and the goal is to clear 25 lines. In B-Type, the level remains constant, and the player chooses the height of the obstacle beforehand.[3]

During play, the tetrominoes are chosen randomly. This leaves the possibility of extended periods with no long bar pieces, which are essential because Tetrises are worth more than clearing the equivalent amount of lines in singles, doubles, or triples. The next piece to fall is shown in a preview window next to the playfield. In a side panel, the game tracks how many of each tetromino has appeared in the game so far.[3]

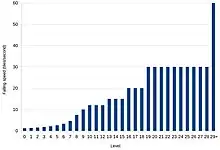

In A-Type, the level advances for every 10 lines cleared. Each successive level increases the points scored by line clears and changes the colors of the game pieces.[3] All levels from 1 to 10 increase the game speed. After level 10, the game speed only increases on levels 13, 16, 19, and 29, at which point the speed no longer increases. On level 29, pieces fall at 1 grid cell every frame, which is too fast for almost all players, and it is thus called the "kill screen".[4] The developers of the game never intended anyone to play past the killscreen, as the game does not properly display the level numbers past 29,[5] but with modern speed techniques, skilled players can play past level 29.[6][4]

When starting a game, the player can select a starting level from 0 to 9, but if the A button is held on the controller when selecting a level, 10 additional levels are added, raising the starting options to 0 to 19.[3] When starting on a later level, the level is not supposed to advance until as many lines have been cleared as it would have taken to advance from level 0 to the starting level.[3] Due to a bug, the levels will begin advancing earlier than intended when starting on level 10 or higher.[7]

At the end of an A-Type game, a substantial score yields an animated ending of a rocket launch in front of Saint Basil's Cathedral. The size of the rocket depends on the score, ranging from a bottle rocket to the Buran spaceplane. In the best ending, a UFO appears on the launch pad and the cathedral lifts off.[7] After a high-level B-Type game, various Nintendo characters perform in front of the cathedral.[7][9] After clearing around 1550 lines, the game is at risk of crashing due to inefficient multiplication operations.[7] Crashing the game in this way is popularly considered "beating the game", a feat first achieved on 21 December 2023 by 13-year-old Willis Gibson, known by his online alias "Blue Scuti".[10][11][12]

Scoring

The score received by each line clear is dependant on the level. Each type of clear, being a single, double, triple, or Tetris, has a base value which is multiplied by the number 1 higher than the current level. For any level , a single will give points, a double will give points, a triple will give points, and a Tetris will give points.[3] The game also awards points for holding the down key to make pieces fall faster, awarding 1 point for every grid cell that a piece is continuously soft dropped.[3] Unlike line clears, this does not scale by level.

This scoring convention makes scoring Tetrises much more efficient than scoring an equivalent amount of lines through smaller line clears. At level 0, a Tetris awards 300 points per line cleared, a triple awards 100 points per line cleared, a double awards 50 points per line cleared, and a single awards 40 points per line cleared.

Speed techniques

One of the most limiting factors in NES Tetris is the speed at which a tetromino can be moved left and right. When a movement key is pressed, the piece will instantly move one grid cell, stop for 16 frames due to delayed auto-shift, before moving again once every 6 frames[13] (10 times a second, as the game runs at 60 fps[14]). At higher levels, waiting for this delay is not feasible because the pieces fall too fast.

A technique known as "hypertapping" is used to circumvent this delay. When hypertapping, horizontal tetromino speed is maximized by rapidly tapping the D-pad more than 10 times per second.[15] The technique involves flexing the bicep until it tremors, so that the high speed tremor taps the thumb on the D-pad.[6] Thor Aackerlund was the first hypertapper,[6] but the technique was very rare until it was popularized by Joseph Saelee in 2018.[16] Jacob Sweet of The New Yorker described hypertapping as "turning [the] thumb into a jackhammer."[6]

In 2020, the "rolling" technique was developed by competitive NES Tetris player Chris "Cheez_fish" Martinez.[17] When rolling, a stationary finger is placed on the D-pad, while the other hand's fingers are drummed across the back of the controller, pushing the buttons up into the stationary hand.[18] To reduce friction, a glove may be worn on the drumming hand.[19] This technique is both much faster and less physically straining than hypertapping[18] – it allows pieces to be shifted horizontally up to 30 times per second, enabling play far past level 29. Since 2021, rolling has been attributed to numerous world records and is used in tournaments such as the Classic Tetris World Championship.[17]

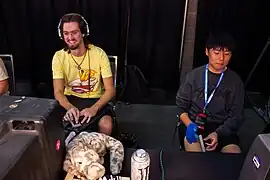

A hypertapper

A hypertapper A hypertapper (left) competes with a roller (right)

A hypertapper (left) competes with a roller (right)- Video of people rolling

Competition

The 1990 Nintendo World Championships were based on A-Type Tetris, Super Mario Bros., and Rad Racer. In each round, contestants were given a total of six minutes to score as much as possible across all three games. As the Tetris score was multiplied 25 times in the final tally, the prevailing strategy was to rush through the other two games to spend all available time in Tetris.[20][21]

In 2009, Harry Hong became the first independently verified person to achieve the maximum score of 999,999 points, known as a max-out score. Earlier plausible but unverified max-out scores were claimed by Thor Aackerlund c. 1990 and Jonas Neubauer c. 2002.[6]

Since 2010, the NES version of Tetris has been featured in the annual Classic Tetris World Championship (CTWC), which consists of a one-on-one competition to score the most points. Specialized cartridges give both competitors the option to use the same piece sequence.[22]

Since 2017, the tournament Classic Tetris Monthly (CTM) has run every month with the same one-on-one format as the CTWC. The CTM rules are more relaxed than those of the CTWC, allowing the usage of emulators and third party hardware.[23][4]

Level 29 "kill screen"

The game pieces reach their maximum falling speed on level 29,[4] when the speed suddenly doubles.[6] According to The New Yorker, level 29 "seems intentionally impossible—a quick way for developers to end the game."[6] Because of this "hard wall", efficient play was required to accumulate points before level 29 ended the game.[4] In the 2000s, level 29 came to be known as the game's "kill screen",[6] though this label would turn out to be inaccurate – level 29 does not make it impossible to continue playing.[5]

Thor Aackerlund, a hypertapper, first demonstrated that level 29 could be beaten in 2011. A recording of Aackerlund reaching level 30 appears in the documentary film Ecstasy of Order: The Tetris Masters.[6] From level 30, the game's level counter stops working correctly, further suggesting that the developers did not believe level 29 could be surpassed.[4][5][24] Level 31 was first reached in 2018 by 15-year-old hypertapper Joseph Saelee,[25] and by 2020 hypertappers had gone as far as level 38.[26]

Kyle Orland of Ars Technica writes that as a result of the rolling technique introduced by Martinez in 2020, "players were getting good enough to effectively play indefinitely on the same 'Level 29' speed that had been considered an effective kill screen just a few years earlier."[26] Unexpected behaviors of the game become relevant at very high levels. From level 138, a byte overflow causes Tetris to load color palettes from unrelated areas of memory, creating unusual and unintended game piece colors.[26][7] In particular, levels 146 and 148 – called the "dusk" and "charcoal" levels – make the game pieces extremely difficult to see against the black background, hindering further progression.[26][28] In 2014, an AI researcher discovered that Tetris is at risk of crashing after about 1550 lines are cleared,[7] corresponding to level 155.[26]

In December 2023, 13-year-old roller Willis Gibson from Stillwater, Oklahoma was the first to complete the "charcoal" level 148.[29] He continued playing, and deliberately caused Tetris to crash on level 157. Because Tetris had been considered unwinnable (due to games necessarily ending with "topping out"), Gibson is credited with being the first person to "beat the game" since its release in 1989.[30][31][32] In a statement, Tetris Company CEO Maya Rogers congratulated Gibson for his "feat that defies all preconceived limits" of Tetris.[33] Cofounders Alexey Pajitnov and Henk Rogers met Gibson in January 2024, calling his playthrough an "amazing, amazing achievement."[34]

Due to extremely prolonged games, the Classic Tetris World Championship has modified their competition cartridges in 2023 to include a "super killscreen" at level 39.[22]

Development

Licensing

By 1989, about six companies claimed rights to create and distribute the Tetris software for home computers, game consoles, and handheld systems.[35] ELORG, the Soviet bureau that held the ultimate copyright, claimed that none of the companies were legally entitled to produce an arcade version, and signed those rights over to Atari Games. Non-Japanese console and handheld rights were signed over to Nintendo.

Tetris was shown at the January 1988 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, where it was picked up by Dutch-born American games publisher Henk Rogers, then based in Japan. This eventually led to an agreement brokered with Nintendo where Tetris became a launch game for Game Boy and bundled with every system.[36]

Implementation

The Nintendo home release was developed by Gunpei Yokoi. Pajitnov is credited for the "original concept, design and program"[3] but was not directly involved in developing this version.[37]

The NES does not have hardware support for generating random numbers.[38] A pseudo-random number generator was implemented with a 16-bit linear feedback shift register. The algorithm produces a close, but slightly uneven distribution of the seven types of game pieces; for every 224 pieces, there is one fewer long bar piece than would be expected from an even distribution.[7]

The game's code includes an unfinished and inaccessible two-player versus mode, which sends rows of garbage blocks (with one opening) to the bottom of the opponent's board when lines are cleared. This feature may have been scrapped due to a rushed development schedule, or to promote sales of the Game Link Cable which enables a two-player mode in Nintendo's Game Boy Tetris.[7]

Music

The soundtrack was written by Nintendo composer Hirokazu Tanaka, who also scored the Game Boy version.[36] Focusing on Russian classical music,[8] the soundtrack features arrangements of "The Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy" from Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker and the overture from Georges Bizet's opera Carmen. The former replaces the arrangement of "Korobeiniki",[7] present in the Game Boy version, which has become strongly associated with Tetris.[36]

Release and reception

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | |

| Aktueller Software Markt | 8.2/12[40] |

| Computer Entertainer |

Tetris was marketed extensively for the 1989 Christmas season.[42] Television advertising used the slogan "You've been Tetris-ized!", referring to the Tetris effect.[43] The tagline "From Russia with fun!" appears on the game's cover, referencing From Russia, with Love by Ian Fleming.[44][45]

In its first six months of release by 1990, Nintendo's NES version of Tetris had sales of 1.5 million copies totaling $52 million (equivalent to $123 million in 2022), surpassing Spectrum HoloByte's versions for personal computers at 150,000 copies for $6 million (equivalent to $14.8 million in 2022) in the previous two years since 1988.[46] As of 2004, 8 million copies of the NES version were sold worldwide.[47] Unlike the Game Boy version,[48] the NES release was not made available for purchase on Nintendo's Virtual Console.[49]

Michael Suck of Aktueller Software Markt considered the game a success, praising the adjustable starting level and music. Suck considered the graphics to be adequate, noting that they do not overwhelm the senses.[40]

IGN noted that "almost everyone" regarded Nintendo's Tetris as inferior to Atari's Tetris, which was pulled from shelves due to licensing issues.[50] Computer Entertainer recommended Nintendo's Tetris only to consumers who had not played Atari's version, which it says has superior graphics, gameplay and options – further calling its removal from stores "unfortunate for players" of puzzle games.[41] Electronic Gaming Monthly called Atari's version "more playable and in-depth" than Nintendo's.[51]

Legacy

Tetris & Dr. Mario (1994) features an enhanced remake of Tetris.[52] Tetris Effect: Connected (2020) includes a game mode that simulates the rules and visuals of Tetris for the NES.[53][54]

The events that lead to Nintendo acquiring the license to publish a Tetris game for consoles are explained in BBC's TV documentary Tetris: From Russia with Love (2004), as well as a dramatic retelling in Tetris (2023).[55]

Since 2018, Nintendo's Tetris has experienced a resurgence in popularity with a younger audience. In 2020, more people attained a max-out score than from 1990 to 2019 combined.[6]

Use in research

In 2018, 11 Tetris experts were instructed to play with the next piece preview window disabled ("no next box"). Their average score was found to drop dramatically, from 465,371 in control games to 6,457 with no next box. The author notes that even though one participant went on to become that year's world champion, no player was recorded scoring a tetris[lower-alpha 2] during any of the no next box games.[56]

In a 2023 study, 160 people were recorded playing NES Tetris. The recordings suggested that novice players blink less than usual while playing Tetris, whereas experienced players remained closer to their normal blinking rate. The study concludes that a person's Tetris ability can be assessed by their blink rate during the first minute of play.[57]

Notes

- ↑ The level counter erroneously displays E9 because level 146 is far outside the normal range of levels that were defined by the developers.[24]: 2m38s [7]

- ↑ Scoring a tetris refers to the act of clearing four lines at once with a long bar piece.

References

- ↑ "Tetris | video game | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- ↑ "Products: Family Computer". Bullet-Proof Software. Archived from the original on August 23, 2000.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tetris Instruction Booklet (PDF). USA: Nintendo of America. 1989. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "How Gen Z is pushing NES Tetris to its limits". Engadget. May 6, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Good, Owen S. (April 13, 2019). "Elite Tetris player takes the NES version where no one has gone before". Polygon. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Sweet, Jacob (March 26, 2021). "The Revolution in Classic Tetris". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Birken, Mike (January 28, 2014). "Applying Artificial Intelligence to Nintendo Tetris". Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- 1 2 Sheff, David (1994). Game Over: How Nintendo Conquered The World. United Kingdom: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0307800749.

- ↑ Oxford, David (July 4, 2019). "Mario Mania: Game Cameos for the Fan's Complete Collection – Tetris for NES". Old School Gamer Magazine. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ↑ Winslow, Levi (January 2, 2024). "Three Decades Later, Someone Has Finally Beaten Tetris On NES". Kotaku. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ↑ Paul, Andrew (January 2, 2024). "A 13-year-old wunderkind is the first human to 'beat' Tetris". Popular Science. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ↑ Ferreira Santos, Sofia (January 3, 2024). "Tetris: US teenager claims to be first to beat video game". BBC News. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ↑ "What is DAS and Hyper Tapping in Tetris - Simon Laroche". simon.lc. October 30, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ↑ "PlatformFramerates". TASVideos. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- ↑ Gach, Ethan (October 22, 2018). "16-Year-Old Dethrones Tetris World Champion With Difficult Hyper-Tap Technique". Kotaku. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ↑ Karnadi, Chris (July 21, 2022). "Teens are rewriting what is possible in the world of competitive Tetris". Polygon. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- 1 2 Bankhurst, Adam (April 29, 2021). "NES Tetris Players Are Using a Special Technique Called Rolling to Set New World Records". IGN. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- 1 2 "NES Tetris Players Call It 'Rolling,' And They're Setting New World Records". Kotaku. April 26, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ↑ Marshall, Jessica (November 16, 2023). "Boy Wonder: Stillwater teen places third in Classic Tetris World Championship". Stillwater News Press. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ↑ McGuire, Keegan (February 18, 2022). "The Untold Truth Of The Nintendo World Championship". Looper. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ↑ Nauert, Donn (June 1990). "The Biggest "Easter Egg" of All". VideoGames & Computer Entertainment. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- 1 2 "Official Classic Tetris World Championship Site". Retrieved October 22, 2023.

- ↑ Bennett-Cohen, Justin (December 16, 2021). "The Classic Tetris Monthly Tournament: What Is It and How Do You Compete?". MUO. Retrieved April 18, 2023.

- 1 2 Sharma, Palki (January 4, 2024). "13-year-old Becomes First Human to Beat Tetris: All You Need to Know". Vantage with Palki Sharma. Firstpost. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ↑ Neumann, Sean (October 19, 2018). "This Bartender Is Secretly the Greatest Tetris Player in the World". Vice. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orland, Kyle (January 2, 2024). "34 years later, a 13-year-old hits the NES Tetris "kill screen"". Ars Technica. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ↑ Randall, Harvey (January 3, 2024). "After 34 years, a 13 year-old prodigy has become the first person to 'beat' Tetris by reaching the holy grail of high-level play: a 'true killscreen'". PC Gamer. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ↑ Bailey, Kat (January 2, 2024). "'Impossible' Tetris NES Beaten for the First Time in 34 Years by 13-Year-Old Phenom". IGN. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ↑ Elmquist, Jason (January 3, 2024). "Wunderkind: Stillwater teen becomes first documented human to 'beat' Tetris". Stillwater News Press. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ↑ Montgomery, Blake (January 3, 2024). "Oklahoma 13-year-old believed to be first person ever to beat Tetris". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ "Oklahoma 13-year-old becomes first person to beat Tetris". YouTube. The Guardian. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ Carroll, Rory (January 4, 2024). "Thirteen-year-old becomes first player to beat Tetris". Reuters.

- ↑ Hamilton, David (January 4, 2024). "13-year-old gamer becomes the first to beat the 'unbeatable' Tetris — by breaking it". Associated Press. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ↑ "13-year-old meets Tetris creator after beating original game". NBC News. January 5, 2024. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ "From Russia with Litigation". Next Generation. No. 26. Imagine Media. February 1997. p. 42.

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Bobbie (June 2, 2009). "How Tetris conquered the world, block by block". The Guardian.

- ↑ Cohen, Rebecca (January 5, 2024). "Teen who beat Tetris gets a surprise meeting with game's creator". NBC News. Retrieved January 7, 2024.

- ↑ Ngo, Trang; Williams, Aaron (September 2022). Entropy Lost: Nintendo’s Not-So-Random Sequence of 32,767 Bits (PDF). FDG '22: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games. Article 65, pp. 1-10.

- ↑ Weiss, Brett Alan. "Tetris". AllGame. Archived from the original on February 16, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2014.

- 1 2 Suck, Michael (November 1989). "Konvertierungen auf einen Blick: Tetris". Aktueller Software Markt (in German).

- 1 2 "The Video Game Update: Tetris". Computer Entertainer. 8 (8): 11. November 1989. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ↑ Coffin, Deborah (1990). "Tetris: A Metaphor for Life". ETC: A Review of General Semantics. 47 (1): 72–76. JSTOR 42577174.

- ↑ Higgins, Chris (June 6, 2015). "This Weekend in Recent History". Mental Floss. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ Gibbons, William (2009). "Blip, Bloop, Bach? Some Uses of Classical Music on the Nintendo Entertainment System". Music and the Moving Image. 2 (1): 40–52. doi:10.5406/musimoviimag.2.1.0040. JSTOR 10.5406/musimoviimag.2.1.0040.

- ↑ Paiva de Oliveira, Raul; Bisoffi, Rafael Augusto Bonin (October 16, 2013). Nationalism in an abstract game: How the Tetris soundtrack determines its cultural markedness (PDF). Proceedings of SBGames 2013. São Paulo. pp. 386–394. ISSN 2179-2259.

- ↑ Dvorchak, Robert (June 17, 1990). "Soviet Game Conquers the Free Market : Technology: Tetris, an electronic Rubik's Cube, proves to be addictive. Sales are sizzling. Sequel is coming from East Bloc". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 10, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2021.

- ↑ Director/Producer: Magnus Temple; Executive Producer: Nick Southgate (2004). "Tetris: From Russia With Love". BBC Four. Event occurs at 51:23. BBC. BBC Four.

The real winners were Nintendo. To date, Nintendo dealers across the world have sold 8 million Tetris cartridges on the Nintendo Entertainment system.

- ↑ Vincent, Alice (December 31, 2014). "It's game over for Tetris on Nintendo 3DS". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ↑ "The Slow Decline of the Virtual Console". GameZone. May 4, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ↑ Claiborn, Sam. "48. Tetris (Tengen) - Top 100 NES Games". IGN. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ↑ Harris, Steve (November 1989). "Nintendo Ignores 16-bit in '89". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 4. p. 50. See also p. 22.

- ↑ "Now Playing". Nintendo Power. Vol. 70. March 1995. pp. 102–107. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ↑ Viray, Aileen (June 16, 2021). "Tetris Effect: Connected cross-platform multiplayer comes to PS4 this July". PlayStation Blog. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ↑ McWhertor, Michael (October 28, 2020). "Tetris Effect: Connected pays homage to classic NES version". Polygon. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ↑ Pingitore, Silvia (March 19, 2023). "Interview with Tetris creator Alexey Pajitnov". Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ↑ Berry, Jacquelyn (June 2023). "No Next Box, No Experts: A Special Case of Epistemic Behavior in Extreme Tetris Expertise" (PDF). Journal of Expertise. 6 (2): 164–175.

- ↑ Guglielmo, Gianluca; Klincewicz, Michal; Huis in 't Veld, Elisabeth; Spronck, Pieter (October 13, 2023). "Tracking Early Differences in Tetris Performance using Eye Aspect Ratio Extracted Blinks" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Games. doi:10.1109/TG.2023.3324511. ISSN 2475-1502.