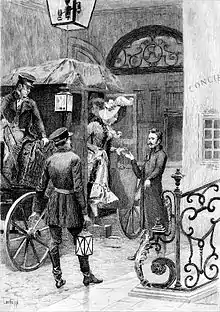

Illustration from an 1897 edition by Oreste Cortazzo | |

| Author | Honoré de Balzac |

|---|---|

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Series | La Comédie humaine |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Publisher | Furne |

Publication date | 1842 |

| Media type | |

| Preceded by | Le Curé de Tours |

| Followed by | L'illustre Gaudissart |

La Rabouilleuse (The Black Sheep, or The Two Brothers) is an 1842 novel by Honoré de Balzac, and is one of The Celibates in the series La Comédie humaine.[1] The Black Sheep is the title of the English translation by Donald Adamson published by Penguin Classics. It tells the story of the Bridau family, trying to regain their lost inheritance after a series of mishaps.

Though for years an overlooked work in Balzac's canon, it has gained popularity and respect in recent years. The Guardian listed The Black Sheep 12 on its list of the 100 Greatest Novels of All Time.[2]

Plot summary

The action of the novel is divided between Paris and Issoudun. Agathe Rouget, who was born in Issoudun, was sent by her father, Doctor Rouget, to be raised by her maternal relatives, the Descoings, in Paris. Doctor Rouget suspects (wrongly) that he is not her biological father. In Paris she marries a man named Bridau and they have two sons, Philippe and Joseph. Monsieur Bridau dies relatively young, Philippe, who is the elder and his mother's favourite, becomes a soldier in Napoleon's armies and Joseph becomes an artist. Philippe is shown to be a courageous soldier but is also a heavy drinker and gambler. He resigns from the army after the Bourbon Restoration out of loyalty to Napoleon. Joseph is a dedicated artist and the more loyal son, but his mother does not understand his artistic vocation.

After leaving the army Philippe takes part in the failed Champ d'Asile settlement in Texas. On returning to France he is unemployed and lives with his mother and Madame Descoings, becoming a financial drain on them, mainly because of his hard drinking and gambling. Philippe becomes estranged from his mother and brother after he steals money from Madame Descoings, which inadvertently leads to her death. The money Philippe steals had been intended by Madame Descoings to purchase a lottery ticket, on which she regularly spends her savings fervently using the same set of numbers each time. On this occasion Descoings' lucky numbers are called yet without a ticket Descoings is unable to claim the three million franc prize, resulting in her going into shock and eventually dying from grief. Philippe is soon afterwards arrested for his involvement in an anti-government conspiracy.

Meanwhile, in Issoudun, Agathe's elder brother, Jean-Jacques, takes in an ex-soldier named Max Gilet as a boarder. Max is suspected of being his illegitimate half brother. Max and Jean-Jacques' servant, Flore Brazier, work together to control Jean-Jacques. Max socialises with and leads a group of local young men who call themselves The Knights of Idleness and frequently play practical jokes around the town. Two of these are against a Spanish immigrant named Fario, destroying his cart and his grain and therefore ruining his business.

It is now that Joseph and his mother travel to Issoudun to try to persuade Jean-Jacques to give Agathe money to help cover Philippe's legal costs. They stay with their friends the Hochons. Jean-Jacques and Max give them only some old paintings but only Joseph recognises their value. Joseph tells of his luck to the Hochons, not realising that their grandsons are friends of Max. Afterwards when Max discovers the value of the paintings he coerces Joseph into returning them. Then one night while Max is out walking he is stabbed by Fario. As Max is recovering he decides to blame Joseph for the stabbing. Joseph is arrested but later cleared and released, and he and his mother return to Paris.

In the meantime Philippe has been convicted for his plotting. However he cooperates with the authorities and gets a light sentence of five years’ police supervision in Autun. Philippe gets his lawyer to change the location to Issoudun in order to claim his mother's inheritance for himself. He challenges Max to a duel with sabres and kills him. He then takes control of Jean-Jacques and his household, forcing Flore to become Jean-Jacques' wife.

Philippe marries Flore after the death of Jean-Jacques. Flore dies soon afterwards. The book hints that both of these deaths are arranged by Philippe but is not explicit about the means. Through his connexions Philippe has now obtained the title Comte de Brambourg. Philippe's attempted marriage to a rich man's daughter falls through when his friends disclose his past to her father. Prior to this, Agathe, who now runs a successful lottery office thanks to Joseph, still views Philippe as a good son despite his neglect of the family. In contrast, she views Joseph as a disappointment, indifferent to his art, which to her is only bringing him into debt. Agathe writes to Philippe to ask him to visit her and help Joseph financially but he bluntly refuses and wishes to cut all ties with the family in case they jeopardise his noble standing. Philippe's cruelty results in Agathe falling into despair and becoming fatally ill. During confession on her deathbed a priest chastises Agathe for neglecting her only honest son, Joseph, while offering her love only to Philippe. Seeing the error of her ways Agathe realises she has not loved Joseph as well as he deserves and begs for his forgiveness, although Joseph consoles her by claiming she is a good mother and despite not understanding art she has always provided for him, allowing him to work as an artist. Joseph spends the next two weeks attending to his mother until finally attempting to reconcile Philippe and their mother before her death, which fails. Philippe's fortunes take a turn for the worse after some unsuccessful speculation and he rejoins the army to take part in the war in Algeria, where he is killed in action, so that in the end Joseph, now a successful artist, inherits the family fortune and Philippe’s title as Comte de Brambourg, much to his amusement.

Explanation of title

‘La Rabouilleuse’ is the nickname of Flore Brazier used behind her back by the people of Issoudun. Max takes offence when some of his friends use it in conversation. Adamson translates the term as ‘the Fisherwoman’. The nickname is a reference to the job that she did as a young girl when helping her uncle to catch for crayfish by stirring up (‘rabouiller’) the streamlets.[3] That was before she became a servant to the Rouget household. The English title of the book therefore moves the focus from her to the Bridau brothers.[4]

Adaptations

In 1903 Emile Fabre adapted the story to a play with the same name,[5] itself later adapted to two movies called Honor of the Family (in 1912 and 1931). The book was broadcast by BBC Radio 4 as its Classic Serial on Sunday 17 August and Sunday 24 August 2008, with actor Geoffrey Whitehead as the narrator.

The French film The Opportunists (1960) is also based on this novel.

Footnotes

- ↑ Honoré de Balzac. "The Human Comedy: Introductions and Appendix". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Robert McCrum (8 August 2006). "The 100 greatest novels of all time: The list | Books | The Observer". London: Guardian. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ↑ Cerfberr, Anatole; Christophe, Jules François. Repertory of the Comedie Humaine, entry for 'BRIDAU (Flore Brazier, Madame Philippe)'. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 7 April 2018.

- ↑ Adamson, Donald. Translator's Introduction, The Black Sheep, Penguin Classics, 1970

- ↑ Flat, Paul (21 March 1903). "La Rabouilleuse: drame en quatre actes, tiré du roman de Balzac". Theatres. Revue bleue: politique et littéraire (in French). G. Baillière. XIX (12): 379.

Bibliography

- Balzac, Honoré de. La Rabouilleuse. 1842.

- Adamson, Donald. Translator's Introduction, The Black Sheep. Penguin Classics, 1970, pp. 7–20.

- (in French) Hélène Colombani Giaufret, « Balzac linguiste dans Les Célibataires », Studi di storia della civiltà letteraria francese, I-II. Paris, Champion, 1996, p. 695-717.

- (in French) Lucienne Frappier-Mazur, « Max et les Chevaliers : famille, filiation et confrérie dans La Rabouilleuse », Balzac, pater familias, Amsterdam, Rodopi, 2001, p. 51-61.

- (in French) Gaston Imbault, « Autour de La Rabouilleuse », L'Année balzacienne, Paris, Garnier Frères, 1965, p. 217-32.

- Fredric Jameson, « Imaginary and Symbolic in La Rabouilleuse », Social Science Information, 1977, n° 16, p. 59-81.

- Doris Y. Kadish, « Landscape, Ideology, and Plot in Balzac's Les Chouans », Nineteenth-Century French Studies, 1984,n° 12 (3-4), 43–57.

- Dorothy Magette, « Trapping Crayfish: The Artist, Nature, and Le Calcul in Balzac’s La Rabouilleuse », Nineteenth-Century French Studies, Fall-Winter 1983–1984, n° 12 (1-2), p. 54-67.

- Allan H. Pasco, « Process Structure in Balzac’s La Rabouilleuse », Nineteenth-Century French Studies, Fall 2005-Winter 2006, n° 34 (1-2), p. 21-31.

- Donato Sperduto, Oltre il tempo e oltre la cuccagna, Wip Edizioni, Bari, 2023.