The Mothers of Invention | |

|---|---|

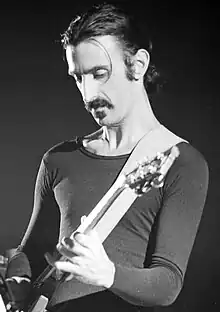

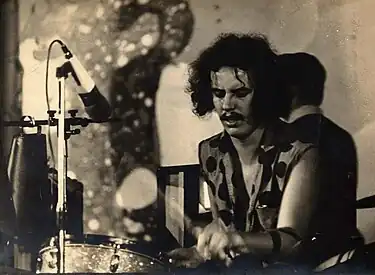

.jpg.webp) The Mothers of Invention touring Europe in 1968. Back row: Roy Estrada, Frank Zappa, Don Preston. Front row: Jimmy Carl Black, Bunk Gardner. | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as |

|

| Origin | Pomona, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Years active |

|

| Labels | |

| Spinoffs | |

| Past members | Personnel |

The Mothers of Invention (also known as the Mothers) was an American rock band from California.[3] Formed in 1964, their work is marked by the use of sonic experimentation, innovative album art, and elaborate live shows.

Originally an R&B band called the Soul Giants, the band's first lineup included Ray Collins, David Coronado, Ray Hunt, Roy Estrada, and Jimmy Carl Black. Frank Zappa was asked to take over as the guitarist following a fight between Collins and Coronado, the band's original saxophonist/leader. Zappa insisted they perform his original material - and on Mother's Day in 1965 - changed their name to the Mothers. Record executives demanded the name be changed, and so "out of necessity", Zappa later said, "We became the Mothers of Invention".

After early struggles, the Mothers earned substantial popular commercial success. The band first became popular playing in California's underground music scene in the late 1960s. With Zappa at the helm, it was signed to jazz label Verve Records as part of the label's diversification plans.[4] Verve released the Mothers of Invention's début double album Freak Out! in 1966, featuring a lineup including Zappa, Collins, Black, Estrada and Elliot Ingber. Don Preston joined the band soon after. Under Zappa's leadership and a changing lineup, the band released a series of critically acclaimed albums, including Absolutely Free, We're Only in It for the Money, and Uncle Meat, before being disbanded by Zappa in 1969. In 1970, he formed a new version of the Mothers that included Ian Underwood, Jeff Simmons, George Duke, Aynsley Dunbar and singers Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan (formerly of the Turtles, but who for contractual reasons were credited in this band as the Phlorescent Leech & Eddie). Later adding another ex-Turtle, bassist Jim Pons, this lineup endured through 1971, when Zappa was injured by an audience member during a concert appearance.

Zappa focused on big-band and orchestral music while recovering from his injuries, and in 1973 formed the Mothers' final lineup, which included drummer Ralph Humphrey, trumpeter Sal Marquez, keyboardist/vocalist George Duke, trombonist Bruce Fowler, bassist Tom Fowler, percussionist Ruth Underwood and keyboardist/saxophonist Ian Underwood. The final album using the Mothers as a backing band, Bongo Fury (1975), featured guitarist Denny Walley and drummer Terry Bozzio, who continued to play for Zappa on non-Mothers releases.

History

Early years (1964–1965)

The Soul Giants were formed in 1964. In early 1965, Frank Zappa was approached by Ray Collins who asked him to take over as the guitarist following a fight between Collins and the group's original guitarist.[5] Zappa accepted, and convinced the other members that they should play his music to increase the chances of getting a record contract.[6] Original leader David Coronado did not think that the band would be employable if they played original material, and left the band.[6] Zappa soon assumed leadership and the role as co-lead singer, even though he never considered himself a singer.[7]

The band was renamed the Mothers, coincidentally on Mother's Day.[8] The group increased their bookings after beginning an association with manager Herb Cohen, while they gradually gained attention on the burgeoning Los Angeles underground music scene.[9] In early 1966, they were spotted by leading record producer, Tom Wilson, when playing Zappa's "Trouble Every Day", a song about the Watts Riots.[10][11] Wilson had earned acclaim as the producer for singer-songwriter Bob Dylan and the folk-rock act Simon & Garfunkel, and was notable as one of the few African Americans working as a major label pop music producer at this time.[12]

Wilson signed the Mothers to the Verve Records division of MGM Records, which had built up a strong reputation in the music industry for its releases of modern jazz recordings in the 1940s and 1950s, but was attempting to diversify into pop and rock audiences. Verve insisted that the band officially rename themselves because "Mother" in slang terminology was short for "motherfucker"—a term that apart from its profanity, in a jazz context connotes a very skilled musical instrumentalist.[13] The label suggested the name "The Mothers Auxiliary", which prompted Zappa to come up with the name "The Mothers of Invention".

Debut album: Freak Out! (1966)

With Wilson credited as producer, the Mothers of Invention, augmented by a studio orchestra, recorded the groundbreaking Freak Out! (1966) which, preceded by Bob Dylan's Blonde on Blonde, was the second rock double album of new material ever released. It mixed R&B, doo-wop, musique concrète,[14] and experimental sound collages that captured the "freak" subculture of Los Angeles at that time.[15] Although he was dissatisfied with the final product—in a late 1960s radio interview (included in the posthumous MOFO Project/Object compilation) Zappa recounted that the side-long closing track "Return of the Son of Monster Magnet" was intended to be the basic track for a much more complex work which Verve did not allow him to complete—Freak Out immediately established Zappa as a radical new voice in rock music, providing an antidote to the "relentless consumer culture of America".[16] The sound was raw, but the arrangements were sophisticated. While recording in the studio, some of the additional session musicians were shocked that they were expected to read the notes on sheet music from charts with Zappa conducting them, since it was not standard when recording rock music.[17] The lyrics praised non-conformity, disparaged authorities, and had dadaist elements. Yet, there was a place for seemingly conventional love songs.[18] Most compositions are Zappa's, which set a precedent for the rest of his recording career. He had full control over the arrangements and musical decisions and did most overdubs. Wilson provided the industry clout and connections to get the group the financial resources needed.[19]

Wilson nominally produced the Mothers' second album Absolutely Free (1967), which was recorded in November 1966, and later mixed in New York, although by this time Zappa was in de facto control of most facets of the production. It featured extended playing by the Mothers of Invention and focused on songs that defined Zappa's compositional style of introducing abrupt, rhythmical changes into songs that were built from diverse elements.[20] Examples are "Plastic People" and "Brown Shoes Don't Make It", which contained lyrics critical of the hypocrisy and conformity of American society, but also of the counterculture of the 1960s.[21] As Zappa put it, "[W]e're satirists, and we are out to satirize everything."[22]

New York period (1966–1968)

The Mothers of Invention played in New York in late 1966 and were offered a contract at the Garrick Theater during Easter 1967. This proved successful and Herb Cohen extended the booking, which eventually lasted half a year.[23] As a result, Zappa and his wife, along with the Mothers of Invention, moved to New York.[24] Their shows became a combination of improvised acts showcasing individual talents of the band as well as tight performances of Zappa's music. Everything was directed by Zappa's famous hand signals.[25] Guest performers and audience participation became a regular part of the Garrick Theater shows. One evening, Zappa managed to entice some U.S. Marines from the audience onto the stage, where they proceeded to dismember a big baby doll, having been told by Zappa to pretend that it was a "gook baby".[26]

Situated in New York, and only interrupted by the band's first European tour, the Mothers of Invention recorded the album widely regarded as the peak of the group's late 1960s work, We're Only in It for the Money (released 1968).[27] It was produced by Zappa, with Wilson credited as executive producer. From then on, Zappa produced all albums released by the Mothers of Invention and as a solo artist. We're Only in It for the Money featured some of the most creative audio editing and production yet heard in pop music, and the songs ruthlessly satirized the hippie and flower power phenomena.[28][29] The cover photo parodied that of the Beatles' Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band,[30] its art provided by Cal Schenkel whom Zappa had met in New York. This initiated a lifelong collaboration in which Schenkel designed covers for numerous Zappa and Mothers albums.[31]

Reflecting Zappa's eclectic approach to music, the next album, Cruising with Ruben & the Jets (1968), was very different. It represented a collection of doo-wop songs; listeners and critics were not sure whether the album was a satire or a tribute.[32] Zappa has noted that the album was conceived in the way Stravinsky's compositions were in his neo-classical period: "If he could take the forms and clichés of the classical era and pervert them, why not do the same ... to doo-wop in the fifties?"[33] A theme from Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring is heard during one song. The album and a single consisting of the songs "Deseri" and "Jelly Roll Gum Drop" were released under the alias Ruben and the Jets.[1][34]

Return to Los Angeles and break up (1968–1969)

Zappa and the Mothers of Invention returned to Los Angeles in the summer of 1968. Despite being a success with fans in Europe, the Mothers of Invention were not faring well financially.[35] Their first records were vocally oriented, but Zappa wrote more instrumental jazz and classical oriented music for the band's concerts, which confused audiences. Zappa felt that audiences failed to appreciate his "electrical chamber music".[36][37] Recorded from September 1967 to September 1968 and released in early 1969, Uncle Meat, the final release by the original Mothers, was a double album of varied music, intended as a soundtrack for a proposed film of the same name.

In November 1968, after Collins had left for the final time, Zappa recruited future Little Feat guitarist Lowell George to replace him.

In 1969, there were nine band members and Zappa was supporting the group himself from his publishing royalties, whether they played or not.[35] 1969 was also the year Zappa, fed up with the label's interference, left MGM Records for Warner Bros.' Reprise subsidiary, where Zappa/Mothers recordings would bear the Bizarre Records imprint.

In late 1969, Zappa broke up the band. He often cited the financial strain as the main reason,[38] but also commented on the band members' lack of sufficient effort.[39] Many band members were bitter about Zappa's decision, and some took it as a sign of Zappa's concern for perfection at the expense of human feeling.[37] Others were irritated by "his autocratic ways",[19] exemplified by Zappa's never staying at the same hotel as the band members.[40] Several members would, however, play for Zappa in years to come. He did, however, start recruiting new band members at this time, even asking Micky Dolenz from The Monkees to join. Zappa had appeared on the series and in the movie Head.[41][42] Remaining recordings with the band from this period were collected on Weasels Ripped My Flesh and Burnt Weeny Sandwich (both released in 1970).

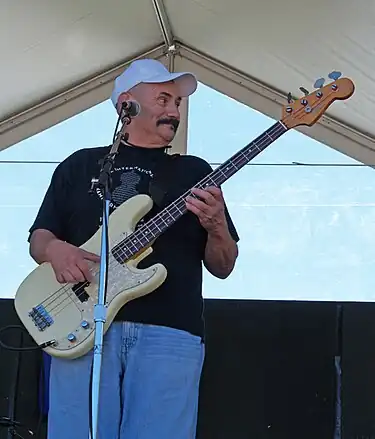

George and Estrada formed Little Feat with Richie Hayward and Bill Payne after the Mothers disbanded.

Rebirth of the Mothers and filmmaking (1970)

Later in 1970, Zappa formed a new version of the Mothers (from then on, he mostly dropped the "of Invention"). It included British drummer Aynsley Dunbar, jazz keyboardist George Duke, Ian Underwood, Jeff Simmons (bass, rhythm guitar), and three members of the Turtles: bass player Jim Pons, and singers Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan, who, due to persistent legal and contractual problems, adopted the stage name "The Phlorescent Leech and Eddie", or "Flo & Eddie".[43]

This version of the Mothers debuted on Zappa's next solo album Chunga's Revenge (1970),[44] which was followed by the double-album soundtrack to the movie 200 Motels (1971), featuring the Mothers, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Ringo Starr, Theodore Bikel, and Keith Moon. Co-directed by Zappa and Tony Palmer, it was filmed in a week at Pinewood Studios outside London.[45] Tensions between Zappa and several cast and crew members arose before and during shooting.[45] The film deals loosely with life on the road as a rock musician.[46] It was the first feature film photographed on videotape and transferred to 35 mm film, a process which allowed for novel visual effects.[47] It was released to mixed reviews.[48] The score relied extensively on orchestral music, and Zappa's dissatisfaction with the classical music world intensified when a concert, scheduled at the Royal Albert Hall after filming, was canceled because a representative of the venue found some of the lyrics obscene. In 1975, he lost a lawsuit against the Royal Albert Hall for breach of contract.[49]

After 200 Motels, the band went on tour, which resulted in two live albums, Fillmore East – June 1971 and Just Another Band From L.A.; the latter included the 20-minute track "Billy the Mountain", Zappa's satire on rock opera set in Southern California. This track was representative of the band's theatrical performances in which songs were used to build up sketches based on 200 Motels scenes as well as new situations often portraying the band members' sexual encounters on the road.[50][51]

Accident, attack and their aftermath (1971–1972)

In December 1971, there were two serious setbacks. While performing at Casino de Montreux in Switzerland, the Mothers' equipment was destroyed when a flare set off by an audience member started a fire that burned down the casino.[52] Immortalized in Deep Purple's song "Smoke on the Water", the event and immediate aftermath can be heard on the bootleg album Swiss Cheese/Fire, released legally as part of Zappa's Beat the Boots II compilation. After a week's break, the Mothers played at the Rainbow Theatre, London, with rented gear. During the encore, an audience member pushed Zappa off the stage and into the concrete-floored orchestra pit. The band thought Zappa had been killed—he had suffered serious fractures, head trauma and injuries to his back, leg, and neck, as well as a crushed larynx, which ultimately caused his voice to drop a third after healing.[52] This accident resulted in him using a wheelchair for an extended period, forcing him off the road for over half a year. Upon his return to the stage in September 1972, he was still wearing a leg brace, had a noticeable limp and could not stand for very long while on stage. Zappa noted that one leg healed "shorter than the other" (a reference later found in the lyrics of songs "Zomby Woof" and "Dancin' Fool"), resulting in chronic back pain.[52] Meanwhile, the Mothers were left in limbo and eventually formed the core of Flo and Eddie's band as they set out on their own.

Top 10 album (1973–1975)

After releasing a solo jazz-oriented album Waka/Jawaka, and following it up with a Mothers album, The Grand Wazoo, with large bands, Zappa formed and toured with smaller groups that variously included Ian Underwood (reeds, keyboards), Ruth Underwood (vibes, marimba), Sal Marquez (trumpet, vocals), Napoleon Murphy Brock (sax, flute and vocals), Bruce Fowler (trombone), Tom Fowler (bass), Chester Thompson (drums), Ralph Humphrey[53] (drums), George Duke (keyboards, vocals), and Jean-Luc Ponty (violin).

Zappa continued a high rate of production through the first half of the 1970s, including the solo album Apostrophe (') (1974), which reached a career-high No. 10 on the Billboard pop album charts[54] helped by the chart single "Don't Eat the Yellow Snow".[55] Other albums from the period are Over-Nite Sensation (1973), which contained several future concert favorites, such as "Dinah-Moe Humm" and "Montana", and the albums Roxy & Elsewhere (1974) and One Size Fits All (1975) which feature ever-changing versions of a band still called the Mothers, and are notable for the tight renditions of highly difficult jazz fusion songs in such pieces as "Inca Roads", "Echidna's Arf (Of You)" and "Be-Bop Tango (Of the Old Jazzmen's Church)".[56] A live recording from 1974, You Can't Do That on Stage Anymore, Vol. 2 (1988), captures "the full spirit and excellence of the 1973–75 band".[56]

Zappa released Bongo Fury in 1975, which featured live recordings from a tour that same year which had reunited him with Captain Beefheart for a brief period.[57] They later became estranged for a period of years, but were in contact at the end of Zappa's life.[58] Bongo Fury was the last new album to be credited to the Mothers.

In 1993, Zappa released Ahead of Their Time, an album of a 1968 live performance by the original Mothers of Invention lineup.

Personnel

| Image | Name | Years active | Instruments | Release contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frank Zappa |

|

|

all releases | |

| Roy Estrada |

|

|

| |

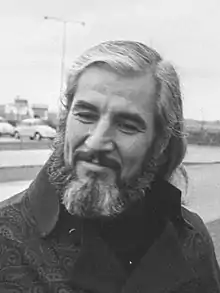

| Jimmy Carl Black | 1964–1969 (died 2008) |

| ||

| Ray Collins |

|

|

| |

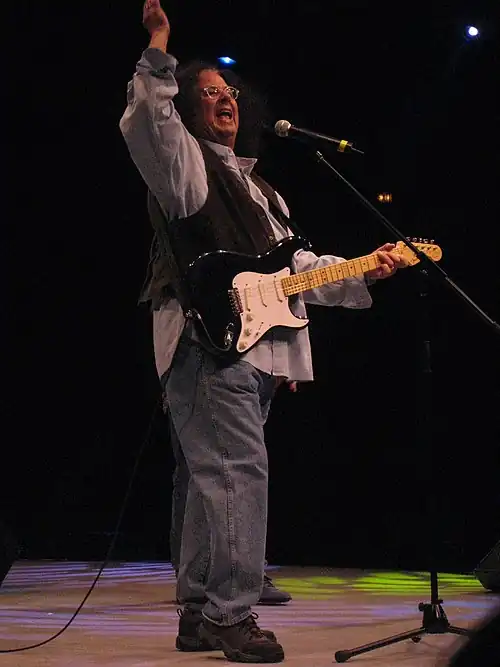

| Don Preston |

|

keyboards |

| |

| David Coronado | 1964 | saxophone | none | |

| Van Dyke Parks | 1965 | keyboards | ||

| Henry Vestine | November 1965 – early 1966 (died 1997) | guitar | ||

| Jim Guercio | early 1966 | |||

| Steve Mann | early 1966 (died 2009) | |||

| Elliot Ingber | early 1966–September 1966 |

| ||

| Denny Bruce | August 1966 | drums | none | |

| Euclid James "Motorhead" Sherwood |

|

|

| |

| Jim Fielder | late 1966–February 1967 |

|

| |

| John Leon "Bunk" Gardner | November 1966–August 1969 | woodwinds |

| |

| Billy Mundi |

|

drums | all releases from Absolutely Free (1967) to Burnt Weeny Sandwich (1970) | |

| Ian Underwood |

|

|

| |

| Art Tripp | March 1968–August 1969 |

|

| |

| Lowell George | November 1968 – May 1969 (died 1979) |

|

| |

| Buzz Gardner | November 1968 – August 1969 (died 2004) |

|

| |

| Aynsley Dunbar | 1970–1971 | drums |

| |

| Mark Volman ("Flo", "The Phlorescent Leach") | vocals |

| ||

| Howard Kaylan ("Eddie") | ||||

| Jeff Simmons |

|

|

Roxy & Elsewhere (1974) | |

| George Duke |

|

|

all releases from 200 Motels (1971) to Bongo Fury (1975) | |

| Jim Pons | February 1971–December 1971 |

|

| |

| Bob Harris | May 1971–August 1971 (died 2001) |

|

Fillmore East – June 1971 (1971) | |

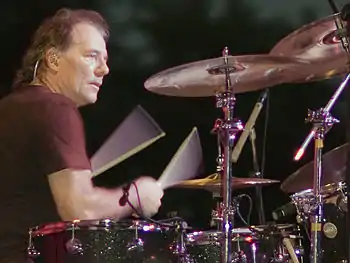

| Ralph Humphrey[59] | early 1973–May 1974 (died 2023)[60] | drums |

| |

| Jean-Luc Ponty | February–August 1973 | violin | Over-Nite Sensation (1973) | |

| Sal Marquez | March 1973–July 1973 |

| ||

| Tom Fowler | 1973–May 1975 | bass | all releases from Over-Nite Sensation (1973) to Bongo Fury (1975) | |

| Ruth Underwood | 1973–December 1975 |

|

| |

| Bruce Fowler |

|

trombone |

| |

| Napoleon Murphy Brock | October 1973–May 1975 |

| ||

| Chester Thompson | October 1973–December 1974 | drums |

| |

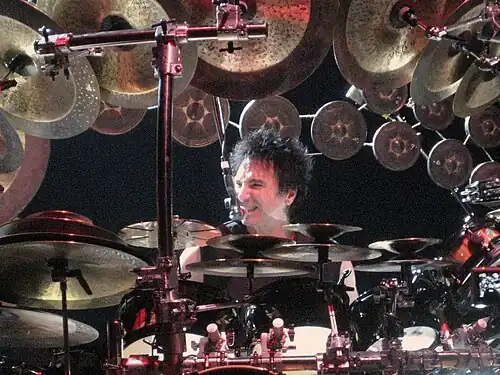

| Terry Bozzio | April 1975–May 1975 | Bongo Fury (1975) | ||

| Denny Walley |

| |||

| Norma Jean Bell | November–December 1975 |

|

none | |

| Novi Novog | September–October 1975 | viola | ||

| Robert "Frog" Camarena | vocals |

|

Timeline

Discography

|

Studio albums

|

Other albums

|

References

- 1 2 Eder, Bruce. "Biography of Ruben and the Jets". AllMusic. Retrieved December 24, 2007.

- ↑ Semley, John (November 26, 2020). "How Weird Was Frank Zappa?". The New Republic. Retrieved June 26, 2023.

It was also the year Zappa and his band, a blues-rock outfit called the Mothers of Invention

- ↑ "Frank Zappa's Mothers of Invention Formed 50 Years Ago in Pomona". The Daily Bulletin. Retrieved March 2, 2022.

- ↑ "The Mothers of Invention | Biography & History". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ↑ Bashe, George-Warren & Pareles 1995.

- 1 2 Zappa & Occhiogrosso 1989, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Swenson, John (March 1980). "Frank Zappa: America's Weirdest Rock Star Comes Clean". High Times.

- ↑ Slaven 2009, p. 42.

- ↑ Walley 1980, p. 58.

- ↑ Miles 2004, p. 103.

- ↑ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 34 – Revolt of the Fat Angel: American musicians respond to the British invaders. [Part 2]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- ↑ Hall, Mitchell K. (2014). The Emergence of Rock and Roll: Music and the Rise of American Youth Culture. Routledge. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-135-05357-4. Extract of page 86

- ↑ Nigel Leigh (March 1993). "Interview with Frank Zappa". The Late Show. Utility Muffin Research Kitchen, Los Angeles, California. BBC2.

- ↑ Lowe 2006, p. 25.

- ↑ Walley 1980, pp. 60–61.

- 1 2 Miles 2004, p. 115.

- ↑ Miles 2004, p. 112.

- ↑ Watson 2005, pp. 10–11.

- 1 2 Miles 2004, p. 123.

- ↑ Lowe 2006, p. 5.

- ↑ Lowe 2006, pp. 38–43.

- ↑ Miles 2004, pp. 135–138.

- ↑ James, 2000, Necessity Is ... , pp. 62–69.

- ↑ Miles 2004, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Miles 2004, p. 147..

- ↑ Zappa & Occhiogrosso 1989, p. 94.

- ↑ Huey, Steve. "We're Only in It for the Money. Review". AllMusic. Retrieved January 2, 2008.

- ↑ Watson 2005, p. 15.

- ↑ Walley 1980, p. 90.

- ↑ As the legal aspects of using the Sgt Pepper concept were unsettled, the album was released with the cover and back on the inside of the gatefold, while the actual cover and back were a picture of the group in a pose parodying the inside of the Beatles album. Miles 2004, p. 151

- ↑ Watson 1995, p. 88.

- ↑ Lowe 2006, p. 58.

- ↑ Zappa & Occhiogrosso 1989, p. 88.

- ↑ Frank Zappa, "Serious Fan Mail", Greasy Love Songs, Zappa Records ZR20010, 2010.

- 1 2 Walley 1980, p. 116.

- ↑ Slaven 2009, pp. 119–120.

- 1 2 Miles 2004, pp. 185–187.

- ↑ Zappa & Occhiogrosso 1989, p. 107.

- ↑ Slaven 2009, p. 120.

- ↑ Miles 2004, p. 116.

- ↑ "'Oh, my God – talk about a redirection': Micky Dolenz on his most interesting post-Monkees job offer". Something Else!. August 27, 2014. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- ↑ Miles 2004, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Miles 2004, p. 201.

- ↑ Miles 2004, p. 205.

- 1 2 Watson 1995, p. 183.

- ↑ Miles 2004, p. 207.

- ↑ Starks 1982, p. 153.

- ↑ Lowe 2006, p. 94.

- ↑ Zappa & Occhiogrosso 1989, pp. 119–137.

- ↑ Miles 2004, pp. 203–204.

- ↑ During the June 1971 Fillmore concerts Zappa was joined on stage by John Lennon and Yoko Ono. This performance was recorded, and Lennon released excerpts on his album Some Time In New York City in 1972. Zappa later released his version of excerpts from the concert on Playground Psychotics in 1992, including the jam track "Scumbag" and an extended avant-garde vocal piece by Ono (originally called "Au"), which Zappa renamed "A Small Eternity with Yoko Ono".

- 1 2 3 Zappa & Occhiogrosso 1989, pp. 112–115.

- ↑ "Ralph Humphrey - DRUMMERWORLD". Archived from the original on April 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Frank Zappa > Charts and Awards > Billboard Albums". AllMusic. Retrieved January 3, 2008.

- ↑ Huey, Steve. "Apostrophe ('). Review". AllMusic. Retrieved January 3, 2008.

- 1 2 Lowe 2006, pp. 114–122.

- ↑ Miles 2004, p. 248.

- ↑ Miles 2004, p. 372.

- ↑ "Ralph Humphrey's page on Drummerworld". Drummerworld.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ↑ Lawrence, George (April 30, 2023). "In Memorian: Ralph Humphrey". Not So Modern Drummer. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

Sources

- Bashe, Patricia Romanowski; George-Warren, Holly; Pareles, Jon (1995). The New Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock & Roll (2nd ed.). New York: Fireside/Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684810447. OCLC 987950913.

- Lowe, Kelly (2006). The words and music of Frank Zappa. Westport, Conn: Praeger. ISBN 9780313054570. OCLC 231671209.

- Miles, Barry (2004). Zappa. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 9780802142153. OCLC 852013692.

- Slaven, Neil (2009). Electric Don Quixote. London: Music Sales. ISBN 9780857120434. OCLC 1028956730.

- Starks, Michael (1982). Cocaine Fiends and Reefer Madness : An Illustrated History of Drugs in the Movies. New York: Cornwall Books. ISBN 9780845345047. OCLC 7247337.

- Walley, David (1980). No commercial potential : the saga of Frank Zappa, then and now. New York: E.P. Dutton. ISBN 9780525931539. OCLC 7067436.

- Watson, Ben (1995). Frank Zappa : The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312119188. OCLC 1035086199.

- Watson, Ben (2005). Frank Zappa : the complete guide to his music. London: Omnibus. ISBN 9780857127389. OCLC 934706705.

- Zappa, Frank; Occhiogrosso, Peter (1989). The real Frank Zappa book. New York: Poseidon Press. ISBN 9780671638702. OCLC 910366907.

External links

- The Mothers of Invention at AllMusic

- The Mothers of Invention discography at Discogs

- Jimmy Carl Black website

- "The Grande Mothers Re:Invented" – MySpace page

- The Mothers of Invention interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

.jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)