Theophilus H. Holmes | |

|---|---|

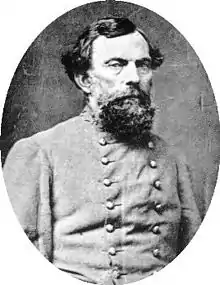

Holmes in uniform, c. 1862 | |

| Birth name | Theophilus Hunter Holmes |

| Born | November 13, 1804 Sampson County, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | June 21, 1880 (aged 75) Fayetteville, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Buried | MacPherson Presbyterian Church, 35°03′38.6″N 78°56′44.1″W / 35.060722°N 78.945583°WFayetteville, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Reserve Brigade, Army of the Potomac District of Fredericksburg Department of North Carolina District of Aquia Trans-Mississippi Department District of Arkansas North Carolina Reserve Forces |

| Battles/wars | |

| Relations | Gabriel Holmes (father) |

| Signature | |

Lieutenant-General Theophilus Hunter Holmes (November 13, 1804 – June 21, 1880) was an American soldier who served as a senior officer of the Confederate States Army and commanded infantry in the Eastern and Trans-Mississippi theaters of the American Civil War. He had previously served with distinction as an officer of the United States Army in the Seminole and Mexican–American wars. A friend and protégé of Confederate States President Jefferson Davis, he was appointed commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department but failed in his key task, which was to defend the Confederacy's hold on the Mississippi.

Early life and education

Holmes was born in Sampson County, North Carolina, in 1804.[1] His father, Gabriel Holmes, was a former Governor of North Carolina and U.S. Congressman.[2][3] After a failed attempt at plantation managing, Holmes asked his father for an appointment to the United States Military Academy, from which he graduated in 1829. He was ranked 44 out of 46 in his class.[4] Holmes was quite deaf and was rarely aware of loud gunfire.[1]

United States Army

I, who knew [Holmes] from his school-boy days, who served with him in garrison and in field, and with pride watched him as he gallantly led a storming party up a rocky height at Monterey, and was intimately acquainted with his whole career during our sectional war, bear willing testimony to the purity, self-abnegation, generosity, fidelity and gallantry, which characterized him as a man and a soldier.

After graduating, Holmes was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the 7th U.S. Infantry Regiment. In 1838, Holmes attained the rank of captain.[3] During his early services, Holmes served in Florida, the Indian Territory, and Texas. Holmes also served in the Second Seminole War, with distinction.[2] In 1841, he married Laura Whetmore, with whom he had eight children.[3] During the Mexican–American War, he was brevetted to major for the Battle of Monterrey in September 1846.[2] This promotion was due to Jefferson Davis witnessing his courageous actions there.[3] He received a full promotion to major of the 8th U.S. Infantry Regiment in 1855.[4]

Confederate States Army

Early service

Almost immediately after the firing on Fort Sumter, Holmes resigned his commission in the U.S. Army and his command of Fort Columbus, on Governors Island in New York City, on April 22, 1861, having accepted a commission as a colonel in the Confederate States Army in March.[2] He commanded the coastal defenses of the Department of North Carolina and then served as a brigadier-general in the North Carolina Militia.[5] He was appointed brigadier-general on June 5, 1861, commanding the Department of Fredericksburg.[3] Holmes was assigned to P. G. T. Beauregard, for the First Battle of Manassas.[4] Beauregard sent Holmes orders to attack the U.S. left, but by the time the orders reached Holmes, the Confederate army was already victorious.[4] Holmes was promoted to major general on October 7, 1861. He subsequently commanded the Aquia District [6] before being assigned to the Department of North Carolina.[3]

Peninsula Campaign

During the Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862, Holmes was moved to the Richmond area to defend it from the U.S. assault on the Confederate capital; thus, he became temporarily attached to the Army of Northern Virginia.[5] His division consisted of the brigades of Brigadier-Generals Junius Daniel, John G. Walker, Henry A. Wise, and the cavalry brigade of Brig. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart. On June 30, 1862, while the Battle of Glendale was fought to the north, Holmes was ordered to cannonade retreating U.S. soldiers near Malvern Hill. His force was repulsed at Turkey Bridge by artillery fire from Malvern Hill and by the U.S. gunboats Galena and Aroostook on the James. His force was in reserve during the Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1, 1862. After the Seven Days Battles, Robert E. Lee expressed displeasure at Holmes's mediocre performance. The two also had fundamental disagreements on strategy. Lee appears to have not been alone in his belief that the nearly 60-year-old Holmes was too old, sluggish, and passive (better as an administrator than a field commander) to wage the aggressive war of movement that Lee planned. In truth, the entire Confederate counterattack in the Seven Days Battles had been handled ineffectively, and many generals were to blame, including Lee himself. Jefferson Davis, in particular, did not think Holmes was any more at fault than the rest of the Army of Northern Virginia's command structure. Nonetheless, his age and unremarkable record in the war up to that point were factors against him, and Lee quickly made it clear that Holmes would not make the cut during the post-Seven Days restructuring of the army. General D. H. Hill, who was known for his sarcastic temperament, also widely spread the story of Holmes, saying, "I thought I heard firing" at Malvern Hill.

Trans-Mississippi Department

Holmes was then reassigned to the command of the Trans-Mississippi Department. On October 10, 1862, Jefferson Davis promoted Holmes to lieutenant-general, but Holmes initially declined, feeling he had done nothing to deserve the promotion. However, Davis urged him, and eventually, Holmes accepted.[4] During his time as commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, Holmes failed to perform his most important duty: defend the Confederacy's hold on the Mississippi River. He refused to send troops to relieve Vicksburg, Mississippi, during the Vicksburg Campaign, leading to a U.S. victory. Holmes, operating from Arkansas, protested that the troops in that state were nearly useless and there was no realistic possibility of using them to relieve Vicksburg. For the most part, the Confederate forces in this remote area were little more than a disorganized mob of militia scattered across all corners of the state. There were few weapons available and even fewer modern ones. For the most part, the soldiers had no shoes, no uniforms, no munitions, no training, organization, or discipline, a situation worsened by the fact that many communities in Arkansas had no government above the village level. People did not pay taxes or have any written laws and strongly resisted any attempt to impose an outside government or military discipline on them. Soldiers in the Arkansas militia did not understand the organization of a proper army or obey orders from above. Even worse, many were in poor physical condition and unable to handle the rigors of a lengthy military campaign. Holmes, for his part, believed that he could muster an army of about 15,000 men in Arkansas, but there would be almost no competent officers to lead it anyway. Further compounding his difficulties were multiple U.S. armies converging on the state from all sides. In this situation, Holmes wrote to Richmond that if, by some miracle, he could organize the Arkansas militia into an army and get them across the Mississippi River, they would desert as soon as they got to the east bank. As another serious difficulty, the remote Trans-Mississippi region had considerably lower support for the Confederate cause than the states of the east. Declaring secession from the United States in 1861 had largely been the decision of the state legislature of Arkansas and was not well received among much of the population. Attempts to enforce conscription into the Confederate army met with resistance. Many locals dodged the draft, became guerrillas, or even joined the U.S. army, resulting in harsh penalties imposed by state governments against draft dodgers.[7]

After numerous complaints were sent to Davis, who had little understanding of events in a region almost 900 miles from Richmond, Holmes was relieved as head of the Trans-Mississippi Department in March 1863.[4]

District of Arkansas

After Holmes was relieved as head of the Trans-Mississippi Department, General Edmund Kirby Smith appointed him head of the District of Arkansas[4] and in June, ordered Holmes to make a desperation attack to take some pressure off the beleaguered Vicksburg garrison. On July 4, the day Vicksburg fell to U.S. General Ulysses Grant's army, Holmes attacked the U.S. garrison at Helena, Arkansas with 8,000 men. He planned a coordinated attack in conjunction with Sterling Price, John S. Marmaduke, James Fleming Fagan, and Governor of Arkansas Harris Flanagin. Despite miscommunication, the Confederate army had some initial success, but after hours of fighting, a general retreat was called. The Confederates pulled back to Little Rock, Arkansas.[4] On July 23, Holmes became ill and temporarily relinquished command in Arkansas to Sterling Price.[1] Price evacuated Little Rock on September 10, and two weeks later Holmes resumed command. In a letter sent to Jefferson Davis on January 29, 1864, Kirby Smith reported that Holmes's age was catching up to him and that he was deficient in energy and suffering memory problems; thus, he needed to be replaced by a younger man. The soldiers he commanded in Arkansas had already taken to sarcastically calling him "Granny". Upon learning of this, an insulted Holmes resigned from his post on February 28.

Later service and life

In April 1864, Holmes commanded the Reserve Forces of North Carolina. Holmes saw little action after being appointed to this new position. He held this position until the end of the war. Holmes, along with General Joseph E. Johnston, surrendered to William Tecumseh Sherman on April 26, 1865.[8] He returned to North Carolina, where he spent the rest of his life as a farmer. Holmes died on June 21, 1880 in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and is buried there in MacPherson Presbyterian Church Cemetery.[3]

See also

Notes

Bibliography

- Dougherty, Kevin, and Michael J. Moore. The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: A Military Analysis. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2005. ISBN 1-57806-752-9.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Hilderman, Walter C. III Theophilus Hunter Holmes: A North Carolina General in the Civil War. McFarland & Company Inc., 2013. ISBN 978-0-7864-7310-6.

- Hoig, Stan. Beyond the Frontier: Exploring the Indian Country. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8061-3052-0.

- Johnston, Joseph E. Narrative of Military Operations. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1874.

- McCrady, Edward, and Samuel A'Court Ashe. Cyclopedia of Eminent and Representative Men of the Carolinas of the Nineteenth Century. Vol. 2. Madison, WS: Brant & Fuller, 1892. OCLC 33265268.

- Welsh, Jack D. Medical Histories of Confederate Generals. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-87338-853-5.

- Williams, Clay. "Theophilus Hunter Holmes." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

Further reading

- Walther, Eric H. William Lowndes Yancey and the Coming of the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 0-8078-3027-5.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

External links

Media related to Theophilus H. Holmes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Theophilus H. Holmes at Wikimedia Commons- Theophilus H. Holmes at Find a Grave