Hinduism is regarded by modern Theosophy as one of the main sources of "esoteric wisdom" of the East. The Theosophical Society was created in a hope that Asian philosophical-religious ideas "could be integrated into a grand religious synthesis."[2][3][4] Prof. Antoine Faivre wrote that "by its content and its inspiration" the Theosophical Society is greatly dependent on Eastern traditions, "especially Hindu; in this, it well reflects the cultural climate in which it was born."[5] A Russian Indologist Alexander Senkevich noted that the concept of Helena Blavatsky's Theosophy was based on Hinduism.[6] According to Encyclopedia of Hinduism, "Theosophy is basically a Western esoteric teaching, but it resonated with Hinduism at a variety of points."[7][note 1]

Philosophical parallels

Merwin Snell's opinion

In 1895, Prof. Merwin Snell (Catholic University of America) published an article, in which he, calling Theosophy a "peculiar form of Neo-Paganism",[10] attempted to determine its attitude to the "various schools of Bauddha and Vaidika" thought, i.e., to Buddhist and Hindu beliefs.[11][note 2]

According to him, there is no connection between Theosophy and Vedism, because the first Vedic texts, the Rigveda, for example, are not containing the doctrine of reincarnation and the law of karma.[14] The Upanishads contain the hidden meaning of the Vedas,[15] and "this is a very important" for understanding Theosophy, since the Upanishads were a basis "of the six great schools of Indian philosophy" which Blavatsky called "the six principles of that unit body of Wisdom of which the 'gnosis', the hidden knowledge, is the seventh."[16] However, according to Snell, only in some cases the Theosophical theory corresponds to the Upanishads, that is, its most important, philosophical, part was "derived from the Darsanas."[note 3][note 4] Thus, Brahman and Maya of the Vedantins, the Purusha and Prakriti of the Sankhya of Kapila, the Yoga of Patanjali, and the Adrishta[20] of the Vaisheshika under the name of karman,[21] all "find their place" in Theosophy.[22] In Snell's opinion, almost all elements of its "religio-philosophical system" are clearly Hindu. Its philosophy is closely linked to the "Vedantized Yoga philosophy, but accepts the main thesis of the pure Advaita school".[23][note 5][note 6]

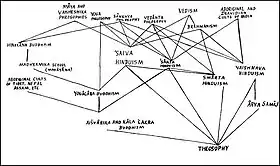

In conclusion, Snell wrote that the "process of Hinduization" of Theosophy can be seen by comparing the first and later works of its leading figures. In his opinion, this process has been greatly influenced by the Society "Arya Samaj", new branch of Vaishnavism (see Fig. 1), which especially emphasized the importance of a study of the Vedas.[25][note 7]

Hinduism and secret teachings

Prof. Donald Lopez noted that in 1878 the founders of the Theosophical Society directed their efforts "toward a broader promotion of a universal brotherhood of humanity, claiming affinities between Theosophy and the wisdom of the Orient, specifically Hinduism and Buddhism."[27] In Jones and Ryan's opinion, the Theosophists "drew freely from their understanding of Eastern thought, particularly Buddhist and Hindu cosmologies."[28][note 8] A British Indologist John Woodroffe noted that the Theosophical teaching was "largely inspired by Indian ideas."[31] Prof. Iqbal Taimni wrote that much of the knowledge about the universe "has always been available, especially in the literature of the ancient religions like Hinduism." But, in most cases, this was presented in the form of difficult-to-understand doctrines. In Taimni's opinion, Theosophy has introduced in them "order, clarity, system and a rational outlook" which allowed us to get a "clear and systematic" understanding of the processes and laws underlying the revealed universe, "both visible and invisible."[32]

According to the Theosophical teaching, the "universal consciousness, which is the essence of all life", lies at the basis of the individual consciousness, and this coincides with the Advaita Vedanta point of view, which states that atman "is identical with Brahman, the universal self".[33] Prof. Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke wrote:

"[Blavatsky's] preference for Advaita Vedanta related to its exposition of the ultimate reality as a monist, nontheistic, impersonal absolute. This nondualist view of Parabrahm as the universal divine principle would become the first fundamental proposition of The Secret Doctrine."[24]

A proem of the book says that there is "an Omnipresent, Eternal, Boundless, and Immutable Principle on which all speculation is impossible, since it transcends the power of human conception and could only be dwarfed by any human expression or similitude."[34] In his book Man, God, and the Universe,[35] Taimni demonstrated several examples showing the coherence of cosmology in The Secret Doctrine with the positions of Hindu philosophy.[note 9]

"In the Absolute there is perfect equilibrium of all opposites and integration of all principles which by their differentiation provide the instruments for running the machinery of a manifested system. The primary differentiation of the Ultimate Reality leads to the appearance of two Realities which are polar in nature and which are called Shiva and Shakti in Hindu philosophy, and the Father-Mother principle in The Secret Doctrine.[37] Shiva is the root of consciousness and Shakti that of power: all manifestations of consciousness are derived from Shiva and those of power from Shakti."[38]

Prof. Robert Ellwood wrote that, according to the Theosophical point of view, spirit and matter are "to be regarded, not as independent realities, but as the two facets or aspects of the Absolute (Parabrahm), which constitute the basis of conditioned Being whether subjective or objective."[39]

According to Hindu philosophy, Shiva consciousness serves as a repository in which the universe is in the pralaya stage. After each period of manifestation, the cosmos, or the solar system, "passes into His Consciousness", in accordance with the eternal alternation of the manifestation phase (Shrishti) and the rest one that is "inherent in the Absolute." This state is "beautifully" described, in Taimni's opinion, in the first stanza of Cosmogenesis in The Secret Doctrine.[40] Thus, the universe in the state of pralaya is in the consciousness of Shiva. In fact, it is "in His Consciousness all the time", and the changes associated with manifestation and pralaya can be viewed as affecting "only the periphery of His Consciousness."[41][note 10]

The Logos of a solar system creates in the "Divine Mind" a thought-form which becomes the basis for the construction of His system. Taimni claimed that this "aspect of the Logos corresponding to Not-Self is called Brahma, or the Third Logos" in Theosophy.[note 11] But a world conceived in this way cannot become, according to Taimni, independent without its being animated by the Logos, just as "a picture in the mind of an artist cannot remain without the artist ensouling it with his attention." The created world animated by the Logos is called Vishnu, the "indwelling Life, or the Second Logos" in Theosophy. "This corresponds to the Ananda aspect which is the relating principle between Sat and Cit or Self and Not-Self," Taimni wrote. But this process of thought-formation, which takes place in consciousness, and not in matter, does not in any way affect the "Logos Himself." He "remains as He was," although He supports and permeates the manifested solar system that He controls. "Having created this world and ensouled it I remain," as Sri Krishna says in The Bhagavad-gita [X, 42]. Thus, the aspect of the Logos, which keeps "unaffected and independent" of the world that He created, "is called Mahesha, or the first Logos" in Theosophy. Taimni explained: "It is the Transcendent Aspect, as Vishnu is the Immanent Aspect and Brahma the Imprisoned Aspect of Divinity, if I may use such a term. The first is related to pure Consciousness, the second to Life and the third to Form."[44]

The Theosophists used the concept of reincarnation common for Hinduism and Buddhism to substantiate the one esoteric core of these religions.[note 12] Thus, for A. P. Sinnett, an author of the Esoteric Buddhism, Gautama Buddha is simply one of a row of mahatmas who have "appeared over the course of the centuries." According to Theosophy, "his next incarnation" that occurred sixty years after his death became Shankara, the "great Vedanta philosopher." Sinnett did not deny that the "uninitiated" researcher would insist on Shankara's date of birth a "thousand years after the death of the Buddha, and would also note Shankara's extreme "antipathy" towards Buddhism. And yet he wrote that the Buddha appeared as Shankara "to fill up some gaps and repair certain errors in his own previous teaching."[46][note 13]

Hinduists and Theosophists

According to John Driscoll, an author of The Catholic Encyclopedia, "India is the home of all theosophic speculation", because the main "idea of Hindu civilization is theosophic." Its evolution, reflected in Indian religious literature, has shaped "the basic principles of theosophy."[48] Prof. Mark Bevir noted that Blavatsky identified India as the "source of the ancient wisdom."[26] She wrote about India the following:

"None is older than she in esoteric wisdom and civilization, however fallen may be her poor shadow—modern India. Holding this country, as we do, for the fruitful hot-bed whence proceeded all subsequent philosophical systems, to this source of all psychology and philosophy a portion of our Society has come to learn its ancient wisdom and ask for the impartation of its weird secrets."[49][note 14]

In 1877, first president of the Theosophical Society Henry Olcott accidentally found out about a movement recently organized in India, whose "aims and ideals, he was given to believe, were identical with those of his own Society." It was the Arya Samaj, founded by one Swami Dayananda, who, as the Theosophists believed, was a member of the same occult Brotherhood, to which their own Masters belonged. Olcott set up "through intermediaries" contact with Arya Samaj and offered to unite.[50]

In May 1878, the union of the two societies was formalized, and the Theosophical Society "changed its name to the Theosophical Society of the Arya Samaj of Aryavarta." But soon Olcott received a translation of the statute and the doctrines of Arya Samaj, which led the Theosophists to some confusion. The views of Swami Dayananda had either "radically changed" or were initially misunderstood. His organization was in fact "merely a new sect of Hinduism", and several years after the arrival of Blavatsky and Olcott in India, the connection between the two societies finally ceased.[51][note 15] Dayananda Saraswati's disappointment was expressed in a form of warning to the members of Arya Samaj on contacts with the Theosophists, whom he called atheists, liars, and egoists.[53] Prof. Lopez noted that the relations that Blavatsky and Olcott established with "South Asians tended to be short-lived." They went to India, believing that Swami Dayananda was, in fact, "an adept of the Himalayan Brotherhood". But in 1882, when he declared that the beliefs of Ceylon Buddhists and Bombay Parsis "both were false religions," Olcott concluded that "the swami was just a swami," but he was not an adept.[54]

Goodrick-Clarke wrote that "educated Indians" were particularly impressed by the Theosophists' defense of their ancient religion and philosophy in the context of the growing self-consciousness of the people, directed against the "values and beliefs of the European colonial powers." Ranbir Singh, the "Maharajah of Kashmir" and a "Vedanta scholar", sponsored Blavatsky and Olcott's travels in India. Sirdar Thakar Singh Sandhanwalia, "founder of the Singh Sabha," became a master ally of the Theosophists.[55][note 16] Prof. Stuckrad noted the wave of solidarity which covered the Theosophists in India had powerful "political implications." He wrote, citing in Cranston's book, that, according to Prof. Radhakrishnan, the philosopher and President of India, the Theosophists "rendered great service" by defending the Hindu "values and ideas"; the "influence of the Theosophical Movement on general Indian society is incalculable."[57]

Bevir wrote that in India Theosophy "became an integral part of a wider movement of neo-Hinduism", which gave Indian nationalists a "legitimating ideology, a new-found confidence, and experience of organisation." He stated Blavatsky, like Dayananda Sarasvati, Swami Vivekananda, and Sri Aurobindo, "eulogised the Hindu tradition", however simultaneously calling forth to deliverance from the vestiges of the past. The Theosophical advocacy of Hinduism contributed to an "idealisation of a golden age in Indian history." The Theosophists viewed traditional Indian society as the bearer of an "ideal religion and ethic."[26]

In Prof. Olav Hammer's opinion, Blavatsky, trying to ascribe the origin of the "perennial wisdom" to the Indians, united "two of the dominant Orientalist discourses" of hers era. Foremost, she singled out the "Aryans of ancient India" into a separate "race." Secondly, she began to consider this "race" as a holder of an "ageless wisdom."[58] According to Hammer, the "indianizing trend" is particularly noticeable in "neo-theosophy." He wrote that a book by Charles W. Leadbeater [and Annie Besant], Man: Whence, How and Whither, in which the Indians play a "central role in the spiritual development of mankind", is one of the typical examples of "emic historiography". Here, the ancient "Aryan race" is depicted by the authors as highly religious.[59]

Subba Row as Theosophist

A Hindu Theosophist Tallapragada Subba Row was born into an "orthodox Smartha Brāhman family." According to his biographer N. C. Ramanujachary, he attracted the attention of Blavatsky with his article "The Twelve Signs of the Zodiac," written in 1881 for a magazine The Theosophist.[60][note 17] According to Prof. Joscelyn Godwin, he showed an unrivaled knowing of esoteric Hindu doctrines and was "the one person known to have conversed with Blavatsky as an equal."[62] The spiritual and philosophical system of which Subba Row was committed is called Tāraka Rāja yoga, "the centre and the heart of Vedāntic philosophy".[63]

His attitude towards Blavatsky changed dramatically after the "Coulomb conspiracy".[64] On 27 March 1885, she wrote, "Subba Row repeats that the sacred science was desecrated and swears he will never open his lips to a European about occultism."[65] In Ramanujachary's opinion, his "deep-rooted" nationalist prejudices clearly appear in such his words:

"It will not be a very easy thing to make me believe that any Englishman can really be induced to labour for the good of my countrymen without having any other motive but sincere feeling and sympathy towards them."[66]

Despite the fact that in 1886 the "atmosphere" became somewhat calmer, Subba Row was "strongly opposed" to Olcott's plans for Blavatsky's return to India.[67] In the Mahatma Letters, it can read about Subba Row the following: "He is very jealous and regards teaching an Englishman as a sacrilege."[68] Nevertheless, his lectures on the Bhagavad Gita,[69] that he delivered in 1886 at the Theosophical Convention, were highly appreciated by many members of the Society. [70]

Parallels of freethinking

- within Hinduism

Religious liberalism in Hinduism became possible due to the anti-dogmatic attitudes that dominated the South Asian tradition, according to which "the highest truth cannot be adequately expressed in words." Thus, every Hindu has the right to freely choose his deity and the path to "supreme truth." In 1995, the Supreme Court of India legally registered tolerance for a different religious position, recognition of the diversity of ways to "liberation" and equal rights of a worshipper in "sacred images" and anyone who is denying such images, as well as "non-attachment to a certain philosophical system."[71][note 18]

- within Theosophy

Prof. Julia Shabanova, referring to the resolutions of the General Council of the Theosophical Society Adyar, wrote that, since members of the Society can be adherents of any religion, not abandoning their dogmas and doctrines, there is no teaching or opinion, no matter where it comes from, which in any way binds the member of the Society and which he could not "free to accept or reject." A recognition of the “three goals of the Society” is the only condition for membership, therefore "neither teacher or author, starting from Blavatsky herself" has not any priority for his teaching or opinion. Every Theosophist has the right to join to any school of thought, according to his choice, but he has no right to impose his choice on others. "Judgments or beliefs do not give the right to privileges" and cannot be the cause of punishment.[72]

Theosophical emblem

According to Stuckrad, when creating the official emblem of the Theosophical Society, some elements were copied, including the swastika, "from the personal seal of Madame Blavatsky."[73] "In India the swastika continues to be the most widely used auspicious symbol of Hindus, Jainas, and Buddhists."[74]

The emblem is crowned with the Hindu sacred word "Om" written in Sanskrit.[75][76] In Hinduism, "Om", representing the unity of atman and Brahman, is being identified with the "entire universe and with its modifications," including temporal, that is, past, present, and future.[1]

Below is written a motto of the Theosophical Society "There is no religion higher than truth." There are several variants of the English translation of the Theosophical motto, which was written in Sanskrit as "Satyāt nāsti paro dharmah."[77] The only correct translation does not exist, because the original contains the word "dharmah" which, according to a Russian Indologist Vladimir Shokhin, is not translated unequivocally into European languages, due to its "fundamental ambiguity."[78]

Blavatsky translated it as "There is no religion (or law) higher than truth," explaining that this is the motto of one of the Maharajas of Benares, "adopted by the Theosophical Society."[79][note 19] Prof. Santucci translated the motto as "There is nothing higher than truth,"[81] Prof. Shabanova —"There is no law higher than truth,"[76] Gottfried de Purucker—"There is no religion (duty, law) higher than truth (reality)."[77] A follower of Advaita Vedanta Alberto Martin said that a maxim "There is no religion higher than truth" can be compared, in relation to an "inspiration or motivation", with one phrase from the Bhagavad Gita which reads: "There is no lustral water like unto Knowledge" (IV, 38).[82] According to Shabanova, the Bhagavad-gita defines dharma as the "essential" duty or goal of a person's life. If we consider the Theosophical motto, as she wrote, in the context that "there is no duty, there is no law, there is no path, along which we can follow, more important than the path to truth," we can get closer to the fuller meaning of this motto.[83][note 20]

Theosophical yoga

Hammer wrote that the Theosophical doctrine of the chakras is a part of the "specific religious" system, which includes a Western scientific and technical rhetoric. Here, the chakras are viewed as "energy vortexes" in the subtle bodies, and this view is at odds with the Indian traditions, where the "chakras are perceived as centers of vital force" for which modern scientific concepts, such as "energy", cannot be applied. According to information obtained from the Tantric sources, it is impossible to ascertain whether the chakras are objectively "existing structures in the subtle body," or they are "created" by a yogi through visualization in the process of his "meditative" practice.[85][note 21]

Woodroffe wrote that a Hindu who practice any form of "spiritual Yoga" usually, unlike the Theosophists,[note 22] does this "not on account of a curious interest in occultism or with a desire to gain 'astral' or similar experiences." His attitude towards this cause is exclusively a "religious one, based on a firm faith in Brahman" and on the desire to unite "with It" in order to receive "Liberation."[88] A Japanese Indologist Hiroshi Motoyama noted that the chakras, according to the Theosophists' statements, are the [psycho-spiritual] organs, which actually exist, while in a traditional Hindu literature they are described as the sets of symbols.[89] Prof. Mircea Eliade wrote that all chakras, always depicted as the lotuses, contain the letters of the Sanskrit alphabet, as well as religious symbols of Hinduism.[90] Woodroffe noted that, in Leadbeater's opinion, at the awakening of the fifth centre a yogi "hears voices" but, according to Shat-chakra-nirupana, the "sound of the Shabda-brahman" is heard at the fourth centre.[91]

Criticism of Theosophy

In Prof. Max Müller's opinion, neither in the Vedas, nor in the Upanishads there are any esoteric overtones announced by the Theosophists, and they only sacrifice their reputation, pandering "to the superstitious belief of the Hindus in such follies."[92]

A French philosopher René Guénon noted that the Theosophical conceptions of evolution are "basically only an absurd caricature of the Hindu theory of cosmic cycles."[93] According to Guénon, the Theosophical motto "There is no religion higher than truth" is a very unfortunate translation of the motto "Satyāt nāsti paro dharmah" which owned by one of the Maharajas of Benares. Thus, in his opinion, the Theosophists not only impudently appropriated the "Hindu device", but also could not correctly translate it. Guénon's translation—"There are no rights superior to those of the Truth".[94]

Prof. Lopez wrote that some Indians, for example, such a "legendary" figure as Vivekananda, after initially "cordial relations with the Theosophists," disavowed the connection between "their Hinduism" and Theosophy.[95] In 1900, Vivekananda, calling Theosophy a "graft of American spiritualism," noted that it was identified by "educated people in the West" as charlatanism and fakirism mixed with "Indian thought," and this was, in his opinion, all the help provided by the Theosophists for Hinduism. He wrote that Dayananda Saraswati "took away his patronage from Blavatskism the moment he found it out. Vivekananda summarized, "The Hindus have enough of religious teaching and teachers amidst themselves even in this Kali Yuga, and they do not stand in need of dead ghosts of Russians and Americans."[96]

In Woodroffe's opinion, despite the fact that the Theosophists widely used the ideas of Hinduism, the meanings they gave to some Hindu terms "is not always" correspond to the meanings that the Hindus themselves placed into these terms. For example, Leadbeater explained the ability of yogi to become "large or small at will (Anima and Maxima Siddhi) to a flexible tube" in the forehead, but the Hindus would say so about this: "All powers (Siddhi) are the attributes of the Lord Ishvara". Woodroffe wrote that one should avoid the terms and definitions adopted by the Theosophical authors. [97] Hammer also noted that in many cases, when the Theosophists borrowed terminology from Sanskrit, they were giving it "entirely new meanings."[98] A Christian theologian Dimitri Drujinin also wrote about the "significant" change by Theosophists the meaning of Hindu terms and content of the concepts when they were used.[99]

A German philosopher Eduard von Hartmann, analyzing Sinnett's book Esoteric Buddhism, has criticized not only the Theosophical concepts, but also the cosmology of Hinduism and Buddhism, on which they are based. In his opinion:

"Indian cosmology cannot rid itself from the constant wavering between sensualistic materialism and a cosmic illusionism. The ultimate reason of this appears to be that the lndians have no idea of objective phenomenality. Because they cannot understand the individualities to be relatively constant centres (conglomerations, groups) of functions of the universal spirit, they must take them either for illusions or for separate senso-material existences. And the latter view is obliged to draw the conclusion that the absolute being from which they emanate or derive their existence must also be senso-material. This can only be avoided and an enlightened idea of spirit can only be arrived at, if one takes our notions of matter to be mere illusions of our senses; the objective matter, however, corresponding with it, to be the product of immaterial forces acting in space, and these forces to be the functions of the one unconscious cosmic force."[100]

See also

Notes

- ↑ According to the researchers in esotericism Emily Sellon and Renée Weber, "it was not until the late nineteenth century, after the advent of the Theosophical movement," that interest in Asian thought appeared.[8]

- ↑ In March 1891, M. M. Snell expressed his opinion on Theosophy in the pages of The Washington Post, after which the newspaper published W.Q. Judge's comment "Tenets of Theosophy."[12] In 1893, Snell was a head of the science section of the First Parliament of the World's Religions.[13]

- ↑ Prof. Olav Hammer wrote that, according to Blavatsky, the main texts of Indian philosophy, the Upanishads, were "expurgated by the brahmins once it became clear to them that they could not be kept entirely out of the reach of individuals of low caste."[17] This was done by removing the "most important" parts of them, although the brahmins have provided the transfer of the main key "among the initiated," so that they could understand the remainder of the text.[18]

- ↑ A Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyov has called the Upanishads the "Theosophical part" of the Vedas.[19]

- ↑ Snell wrote that elements of Buddhism, which are seen in Theosophy (see Fig. 1), have been certainly Hinduized: "When it is remembered that the Advaita and the Yoga are particularly popular among the adherents of the Śaiva form of Hinduism and that the Mahāyāna Buddhism arose from a fusion of Buddhism with the latter, the association of Theosophy with Buddhism, not only in the popular mind, but in that of its adherents, becomes intelligible."[23]

- ↑ As Prof. Goodrick-Clarke noted, Buddhist ideas and Advaita Vedanta were the "common source" of Blavatsky's esoteric doctrine.[24]

- ↑ According to Prof. Mark Bevir, "the most important" Theosophical conception within India was identification of the "universal religion" with the ancient Brahmanism.[26]

- ↑ James Skeen, noting that the ancient Greeks and Hindus believed in evolution, has quoted in the Theosophical book by Virginia Hanson: "In Hindu cosmogony, the beginning of the major evolutionary cycle for this earth, known as a Kalpa, is given as 1,960 million years ago. In theosophical terminology, this would identify the arrival of the life wave on this earth."[29][30]

- ↑ According to Encyclopedia of Hinduism, The Secret Doctrine "remains one of the most influential occult works to appear in the West."[36]

- ↑ According to Hindu philosophy, during the period of "dissolution", the universe collapses "into a mathematical point" that has not any magnitude. This is the "Shiva-Bindu."[42]

- ↑ A European term "the Logos" is equivalent to the Hindu one the "Shabda-Brahman."[43]

- ↑ In a historian Julie Chajes' opinion, reincarnation is a "fundamental principle of Theosophy", which claims that not only individualities are reincarnated, but also the "universes, solar systems, and planets."[45]

- ↑ For more details, see the third volume of The Secret Doctrine.[47]

- ↑ Goodrick-Clarke noted that Hindu philosophy, "in particular Samkara's Advaita Vedanta, the Upanishads, and the Bhagavad Gita," was widely represented in Blavatsky's articles and books.[24]

- ↑ "Theosophy's eclecticism and relativism were profoundly incompatible with Dayananda's fundamentalism, so rapid mutual disenchantment was inevitable."[52]

- ↑ According to Paul Johnson's research, these two Indian leaders may have been prototypes of the Theosophical Mahatmas, Morya and Kuthumi.[56]

- ↑ Senkevich stated that, besides Subba Row, there were also other "talented young men from the Brahmin families" who became the Theosophists, for example, Damodar K. Mavalankar and Mohini Mohun Chatterji.[61]

- ↑ "The same [Hindu] family and even the same person may worship different gods."[71]

- ↑ According to Shabanova, Blavatsky met this Maharaja during hers first travel to India.[80]

- ↑ Ellwood noted that the Bhagavad-gita, "an ancient Hindu text, highly valued by many Theosophists".[84]

- ↑ Tantric practice of the Hindus has always been associated with the "local religious worldview," for example, with some "forms of Kashmiri Shaivism."[86]

- ↑ When the Theosophical Society was created the investigation "the unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in man" was proclaimed its third major task.[87]

References

- 1 2 Степанянц 2009, p. 586.

- ↑ Campbell 1980, Ch. 1.

- ↑ Митюгова 2010.

- ↑ Wakoff 2016.

- ↑ Faivre 2010, p. 86.

- ↑ Сенкевич 2012, p. 457.

- ↑ Jones, Ryan 2006c, p. 448.

- ↑ Sellon, Weber 1992, p. 326.

- ↑ Snell 1895b, p. 258.

- ↑ Snell 1895a, p. 205.

- ↑ Snell 1895b, p. 259.

- ↑ Judge.

- ↑ Chattopadhyaya 1999, p. 159.

- ↑ Snell 1895b, p. 262.

- ↑ Степанянц 2009, p. 822.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1888, p. 278; Snell 1895b, pp. 262–3.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1888, p. 270; Hammer 2003, p. 175.

- ↑ Hammer 2003, p. 175.

- ↑ Соловьёв 1914, p. 295.

- ↑ Степанянц 2009, pp. 58–9.

- ↑ Степанянц 2009, p. 445.

- ↑ Snell 1895b, p. 263.

- 1 2 Snell 1895b, p. 264.

- 1 2 3 Goodrick-Clarke 2008, p. 219.

- ↑ Snell 1895b, p. 265.

- 1 2 3 Bevir 2000.

- ↑ Lopez 2009, p. 11.

- ↑ Jones, Ryan 2006b, p. 242.

- ↑ Hanson 1971, p. 102.

- ↑ Skeen 2002.

- ↑ Woodroffe 1974, p. 14.

- ↑ Taimni 1969, pp. 189–90.

- ↑ Sellon, Weber 1992, p. 323.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1888, p. 14; Percival 1905, p. 205; Santucci 2012, p. 234; Шабанова 2016, p. 91.

- ↑ Taimni 1969.

- ↑ Jones, Ryan 2006a, p. 87.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1888, p. 18.

- ↑ Taimni 1969, p. 162.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1888, p. 15; Ellwood 2014, p. 57.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1888, p. 35.

- ↑ Taimni 1969, pp. 50–1.

- ↑ Woodroffe 1974, pp. 34–5.

- ↑ Subba Row 1888, p. 8; Woodroffe 1974, p. 47.

- ↑ Taimni 1969, p. 88.

- ↑ Chajes 2017, p. 72.

- ↑ Sinnett 1885, pp. 175–6; Lopez 2009, p. 189.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1897, pp. 376–85.

- ↑ Driscoll 1912, p. 626.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1879, p. 5; Kalnitsky 2003, pp. 66–7.

- ↑ Kuhn 1992, p. 110; Goodrick-Clarke 2008, p. 219; Lopez 2009, p. 186; Rudbøg 2012, p. 425.

- ↑ Kuhn 1992, p. 111; Santucci 2012, p. 236; Rudbøg 2012, p. 426.

- ↑ Johnson 1995, p. 62.

- ↑ Ransom 1989, p. 121; Дружинин 2012, p. 21.

- ↑ Olcott 2011, pp. 396, 406; Lopez 2009, p. 186.

- ↑ Goodrick-Clarke 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ Godwin 1994, pp. 302, 329; Johnson 1995, p. 49; Kalnitsky 2003, p. 307; Goodrick-Clarke 2004, p. 12; Lopez 2009, p. 185.

- ↑ Cranston 1993, p. 192; Stuckrad 2005, pp. 126–7.

- ↑ Hammer 2003, p. 120.

- ↑ Besant, Leadbeater 1913, p. 266; Hammer 2003, p. 123.

- ↑ Ramanujachary 1993, p. 21.

- ↑ Сенкевич 2012, p. 349.

- ↑ Godwin 1994, p. 329.

- ↑ Subba Row 1980, p. 364; Ramanujachary 1993, p. 22.

- ↑ Ramanujachary 1993, p. 37.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1973, p. 77; Ramanujachary 1993, p. 41.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1973, p. 318; Ramanujachary 1993.

- ↑ Ramanujachary 1993, p. 38.

- ↑ Barker 1924, p. 70; Ramanujachary 1993, p. 24.

- ↑ Subba Row 1888.

- ↑ Ramanujachary 1993, p. 13.

- 1 2 Канаева 2009, pp. 396, 397.

- ↑ Шабанова 2016, pp. 124–5.

- ↑ Stuckrad 2005, p. 127.

- ↑ Britannica.

- ↑ Emblem.

- 1 2 Шабанова 2016, p. 130.

- 1 2 Purucker 1999.

- ↑ Шохин 2010.

- ↑ Blavatsky 1888, p. xli; Шабанова 2016, p. 123.

- ↑ Шабанова 2016, p. 123.

- ↑ Santucci 2012, p. 242.

- ↑ Martin.

- ↑ Шабанова 2016, p. 29.

- ↑ Ellwood 2014, p. 56.

- ↑ Hammer 2003, pp. 185, 192.

- ↑ Hammer 2003, p. 192.

- ↑ Kuhn 1992, p. 113.

- ↑ Woodroffe 1974, pp. 12–3.

- ↑ Motoyama 2003, p. 189.

- ↑ Eliade 1958, pp. 241–5.

- ↑ Woodroffe 1974, p. 9.

- ↑ Olcott 1910b, p. 61; Lopez 2009, p. 157.

- ↑ Guénon 2004, p. 100.

- ↑ Guénon 2004, pp. 197, 298.

- ↑ Lopez 2009, p. 186.

- ↑ Vivekananda 2018.

- ↑ Woodroffe 1974, pp. 14, 19.

- ↑ Hammer 2003, p. 124.

- ↑ Дружинин 2012, p. 74.

- ↑ Hartmann 1885, p. 176.

Sources

- "Emblem Or Seal". TS Adyar. The Theosophical Society Adyar. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Purucker, G. de, ed. (1999). "Satyat Nasti Paro Dharmah". Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary. Theosophical University Press. ISBN 978-1-55700-141-2. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- "Swastika". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Besant, A.; Leadbeater, C. W. (1913). Man: Whence, How and Whither. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House. OCLC 871602.

- Bevir, M. (2000). "Theosophy as a Political Movement". In Copley, Antony (ed.). Gurus and Their Followers. Oxford University Press. pp. 159–79. ISBN 9780195649581. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Blavatsky, H. P. (October 1879). "What Are The Theosophists?" (PDF). The Theosophist. Bombay: Theosophical Society. 1 (1): 5–7. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ———— (1888). The Secret Doctrine (PDF). Vol. 1. London: Theosophical Publishing Company.

- ———— (1897). Besant, A. (ed.). The Secret Doctrine (PDF). Vol. 3. London: Theosophical Publishing Society.

- ———— (1973) [1925]. The Letters of H. P. Blavatsky to A. P. Sinnett (Reprint ed.). Theosophical University Press. ISBN 1-55700-145-6. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Campbell, B. F. (1980). Ancient Wisdom Revived: A History of the Theosophical Movement. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520039681. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Chajes, J. (2017). "Reincarnation in H. P. Blavatsky's The Secret Doctrine". Correspondences. 5 (1): 65–93. ISSN 2053-7158. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Chattopadhyaya, R. (1999). Swami Vivekananda in India: A Corrective Biography. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120815865. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Cranston, S. L. (1993). HPB: the extraordinary life and influence of Helena Blavatsky, founder of the modern Theosophical movement. G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 9780874776881. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Driscoll, J. T. (1912). "Theosophy". In Herbermann, C. G. (ed.). The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 626–8. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Eliade, M. (1958). Yoga: Immortality and Freedom. Translated by Trask, W. R. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691017648. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Ellwood, R. S. (2014) [1986]. Theosophy: A Modern Expression of the Wisdom of the Ages. Quest Books. Wheaton, Ill.: Quest Books. ISBN 9780835631457. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Faivre, A. (2010). Western Esotericism: A Concise History. SUNY series in Western Esoteric Traditions. Translated by Rhone, Christine. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 9781438433776. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Godwin, J. (1994). The Theosophical Enlightenment. SUNY series in Western esoteric traditions. Albany: SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791421512. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Goodrick-Clarke, N. (2004). Helena Blavatsky. Western esoteric masters series. Berkeley: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-55643-457-X. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ———— (2008). The Western Esoteric Traditions: A Historical Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199717569. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Guénon, R. (2004) [2003]. Theosophy: history of a pseudo-religion. translated by Alvin Moore, Jr. Hillsdale, NY: Sophia Perennis. ISBN 9780900588808. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Hammer, O. (2003) [2001]. Claiming Knowledge: Strategies of Epistemology from Theosophy to the New Age (PhD thesis). Studies in the history of religions. Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004136380. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Hanson, V. (1971). H. P. Blavatsky and The Secret Doctrine. Wheaton, Ill: Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Hartmann, E. (May 1885). "Criticism of Esoteric Buddhism" (PDF). The Theosophist. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House. 6 (8): 175–6.

- Johnson, K. P. (1995). Initiates of Theosophical Masters. SUNY series in Western esoteric traditions. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791425568. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Jones, C.; Ryan, J. (2006a). "Blavatsky, Helena Petrovna". In Melton, J. G. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Encyclopedia of World Religions. Infobase Publishing. pp. 86–7. ISBN 9780816075645. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ————; ———— (2006b). "Krishnamurti, Jiddu". In Melton, J. G. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Encyclopedia of World Religions. Infobase Publishing. pp. 242–4. ISBN 9780816075645. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ————; ———— (2006c). "Tingley, Katherine". In Melton, J. G. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Encyclopedia of World Religions. Infobase Publishing. pp. 447–8. ISBN 9780816075645. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Judge, W. Q. (1891-03-15). "Tenets of Theosophy: Mr. W. Q. Judge Replies to the Strictures of Prof. Snell". The Washington Post. Washington: Beriah Wilkins. 0190-8286. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Kalnitsky, Arnold (2003). The Theosophical Movement of the Nineteenth Century: The Legitimation of the Disputable and the Entrenchment of the Disreputable (D. Litt. et Phil. thesis). Promoter Dr H. C. Steyn. Pretoria: University of South Africa (published 2009). hdl:10500/2108. OCLC 732370968.

- Kuhn, A. B. (1992) [1930]. Theosophy: A Modern Revival of Ancient Wisdom (PhD thesis). American religion series: Studies in religion and culture. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-56459-175-3.

- Kuthumi; et al. (1924). Barker, A. T. (ed.). The Mahatma Letters to A. P. Sinnett from the Mahatmas M. & K. H. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company Publishers. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Lopez, D. (2009). Buddhism and Science: A Guide for the Perplexed. Buddhism and Modernity (Reprint ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226493244. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Martin, A. (2018). "The Celibacy Question". Non-duality magazine. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Motoyama, H. (2003). Theories of the Chakras: Bridge to Higher Consciousness (Reprint ed.). New Age Books. ISBN 9788178220239. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Olcott, H. S. (1910a). "Ch. II. The Fears Of H. P. B.". Old Diary Leaves 1887-92. Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ———— (1910b). "Ch. IV. Formation of the Esoteric Section". Old Diary Leaves 1887-92. Theosophical Publishing House. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ———— (2011). Old Diary Leaves 1875-8. Cambridge Library Collection. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108072939. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Percival, H. W. (1905). "Theosophy". In Gilman, D. C. (ed.). The New International Encyclopaedia. Vol. 19. New York: Dodd, Mead. pp. 204–6.

- Ramanujachary, N. C. (1993). A lonely disciple. Adyar: Theosophical Pub. House. OCLC 30518824.

- Ransom, J. A. (1989). A short history of the Theosophical Society. Adyar: Theosophical Pub. House. ISBN 9788170591221. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Rudbøg, Tim (2012). H. P. Blavatsky's Theosophy in Context (PDF) (PhD thesis). Exeter: University of Exeter. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Santucci, J. A. (2012). "Theosophy". In Hammer, O.; Rothstein, M. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to New Religious Movements. Cambridge Companions to Religion. Cambridge University Press. pp. 231–46. ISBN 9781107493551. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Sellon, E. B.; Weber, R. (1992). "Theosophy and The Theosophical Society". In Faivre, A.; Needleman, J. (eds.). Modern Esoteric Spirituality. New York: Crossroad Publishing Company. pp. 311–29. ISBN 0-8245-1145-X. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Sinnett, A. P. (1885) [1883]. Esoteric Buddhism (5th ed.). London: Chapman and Hall Ltd.

- Skeen, James (2002). Foutz, S. D. (ed.). "Theosophy: A Historical Analysis and Refutation" (PDF). Quodlibet. Chicago, Ill. 4 (2). ISSN 1526-6575. OCLC 42345714. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Snell, M. M. (March 1895). "Modern Theosophy in Its Relation to Hinduism and Buddhism. I". The Biblical World. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 5 (3): 200–5. doi:10.1086/471623. ISSN 0190-3578. S2CID 145176680.

- ———— (April 1895). "Modern Theosophy in Its Relation to Hinduism and Buddhism. II". The Biblical World. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 5 (4): 258–65. ISSN 0190-3578.

- Stuckrad, K. (2005). Western Esotericism: A Brief History of Secret Knowledge. Translated by Goodrick-Clarke, N. London: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 9781845530334. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Subba Row, T. (1888). Discourses on the Bhagavat gita (PDF). The Theosophical Society's Publications. Bombay: Bombay Theosophical Fund. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ———— (1980). Esoteric Writings. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House.

- Taimni, I. K. (1969). Man, God, and the Universe. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House. ISBN 9780722971222. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Vivekananda (2018). "Stray Remarks on Theosophy". Swami Vivekananda: Complete Works. Translated by Kumar, Sanjay. LBA. ISBN 9782377879212. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Wakoff, Michael B. (2016). "Theosophy". In Craig, Edward (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy Online. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780415249126-K109-1. ISBN 9780415250696. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Woodroffe, J. G. (1974) [1919]. The Serpent Power (Reprint ed.). Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486230580. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- In Russian

- Дружинин, Д. (2012). Блуждание во тьме: основные положения псевдотеософии Елены Блаватской, Генри Олькотта, Анни Безант и Чарльза Ледбитера [Wandering in the Dark: The Fundamentals of the Pseudo-theosophy by Helena Blavatsky, Henry Olcott, Annie Besant, and Charles Leadbeater] (in Russian). Нижний Новгород. ISBN 978-5-90472-006-3. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Канаева, Н. А. (2009). "Индуизм" [Hinduism]. In Степанянц, М. Т. [in Russian] (ed.). Индийская философия: энциклопедия (in Russian). М.: Восточная литература. pp. 393–408. ISBN 978-5-02-036357-1. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Митюгова, Е. Л. (2010). "Блаватская Елена Петровна" [Blavatsky Helena Petrovna]. In Стёпин, В. С.; Гусейнов, А. А. (eds.). Новая философская энциклопедия (in Russian). Vol. 1 (2nd add. and corr. ed.). Москва: Мысль. ISBN 9785244011166. OCLC 756276342. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Сенкевич, А. Н. (2012). Елена Блаватская. Между светом и тьмой [Helena Blavatsky. Between Light and Darkness]. Носители тайных знаний (in Russian). Москва: Алгоритм. ISBN 978-5-4438-0237-4. OCLC 852503157. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Соловьёв, В. С. (1914). "Веданта" [Vedanta]. In Соловьёв, С. М. (ed.). Собрание сочинений [Collected Writings] (in Russian). Vol. 10. СПб.: Книгоиздательское Товарищество "Просвещение". pp. 294–7.

- Степанянц, М. Т. [in Russian] (2009). Индийская философия: энциклопедия [Indian Philosophy: encyclopedia] (in Russian). М.: Восточная литература. ISBN 978-5-02-036357-1. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Шабанова, Ю. А. (2016). Теософия: история и современность [Theosophy: History and contemporaneity] (PDF) (in Russian). Харьков: ФЛП Панов А. Н. ISBN 978-617-7293-89-6. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Шохин, В. К. (2010). "Дхарма" [Dharma]. In Стёпин, В. С.; Гусейнов, А. А. (eds.). Новая философская энциклопедия (in Russian). Vol. 1 (2nd add. and corr. ed.). Москва: Мысль. ISBN 9785244011166. OCLC 756276342. Retrieved 13 November 2018.