Thomas Sigismund Stribling | |

|---|---|

T. S. Stribling, photo taken prior to 1907 | |

| Born | March 4, 1881 Clifton, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | July 8, 1965 (aged 84) Florence, Alabama, U. S. |

| Alma mater | University of North Alabama |

| Occupation | Novelist |

| Spouse | Lou Ella Kloss |

Thomas Sigismund Stribling (March 4, 1881 – July 8, 1965) was an American writer. Although he passed the bar and practiced law for a few years, he quickly began to focus on writing. First known for adventure stories published in pulp fiction magazines, he enlarged his reach with novels of social satire set in Middle Tennessee and other parts of the South. His best-known work is the Vaiden trilogy, set in Florence, Alabama. The first volume is The Forge (1931). He won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1933 for the second novel of this series, The Store. The last, set in the 1920s, is The Unfinished Cathedral (1934). Both the second and third novels were chosen as selections by the Literary Guild.

His popularity in the 1920s and 1930s also inspired the adaptation of his works for other mediums. Three of his novels were adapted: Birthright was adapted twice as film, in 1924 (now lost) and 1939 (only part survives). Teeftallow and Fobombo were each adapted as plays under other titles (see Adaptations below) and produced on Broadway in New York City in 1928 and 1932, respectively.

Life

Born March 4, 1881, in Clifton, Tennessee, a small town off the Tennessee River, Thomas Sigismund Stribling was the first child of lawyer Christopher Columbus Stribling and his wife, Amelia Ann (Waits) Stribling. The senior Stribling had served in the Union Army during the American Civil War, while his wife's Waits male relatives had fought for the Confederacy. T.S. Stribling later said that this difference resulted in his being a "doubter and a questioner" (Bain, 433). He spent summers with his Waits grandparents on their farm in Lauderdale County, Alabama, where he later set several of his novels in the city of Florence. He later drew from the family stories of his parents, grandparents and extended family on both sides to create the depth of his post-Reconstruction era novels, which were mostly set in the South.

Stribling completed his high school education at the age of seventeen, at Huntingdon Southern Normal University in 1899, in the nearby town of Huntingdon, Tennessee. By this time Stribling was convinced that he was meant to be a writer, having already sold his first story at the age of 12 for five dollars. He was ready to embark on his future in literature. With that in mind, Stribling became the editor of a small weekly newspaper called the Clifton News. Stribling was hoping to use the Clifton News to enter into his writing career, but he worked there for only about a year before his parents convinced him to return to school and complete his education. In the fall of 1902, Stribling graduated from the Florence Normal School, which later developed as the University of North Alabama, in Florence, Alabama. Stribling earned his teaching certification in one year for grades through high school.

Early career

In 1903, Stribling moved to Tuscaloosa, to teach at Tuscaloosa High School. He taught both mathematics and physical education. He taught there for one year before departing, having "no idea whatever of discipline" in the classroom (Kunitz, 1359); he preferred to continue his own education.

In 1905, Stribling completed his law degree at the University of Alabama School of Law. He passed the bar but used his newly earned degree for only a brief time. In fewer than two years, he served as clerk in the Florence law office of George Jones; as one of the practicing lawyers in the Florence law office of Governor Emmett O'Neal; and as a lawyer in the law office of John Ashcraft. Instead of working on clients' cases, Stribling was using the office supplies, typewriter, and paid hours to perfect his writing craft. Under the advice of his fellow lawyers, Stribling gave up practicing law in 1907.

Writing career

After moving to Nashville, Tennessee in 1907, Stribling picked up a job at the Taylor-Trotwood Magazine as a writer, salesman of ads and subscriptions, and "a sort of sublimated office boy." (Kunitz, 1359) While working there, Stribling had two works of fiction published: The Imitator and The Thrall of the Green, both reflecting the social themes for which he would later become renowned.

Repeating his pattern and encouraged by his small success, Stribling left the magazine in 1908. He moved to New Orleans where he produced "Sunday-school stories at the phenomenal rate of seven per day; many of these stories were eventually published by denominational publishing houses." (Martine, 73) Stribling wrote many more Sunday-school stories.

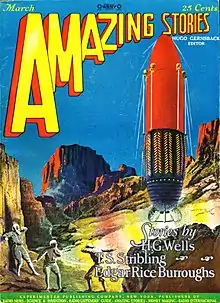

He became even better known for his adventure stories for boys, which were printed in various pulp magazines such as The American Boy, Holland's Magazine, The Youth's Companion, Adventure and Everybody's Magazine. These writings enabled Stribling, for the first time, to live off the profits of his creative ability. For Adventure, Stribling wrote detective stories featuring his psychologist sleuth Doctor Poggioli.[1] Stribling also wrote some science fiction stories with satirical undertones, such as "The Green Splotches" (1920), about aliens in South America, and "Mogglesby" (1930), featuring intelligent apes.[2]

Novels

In 1917, The Cruise of the Dry Dock was published in a limited print run of 250 copies. This was Stribling's first effort at a novel. It was strongly influenced by his adventure writings for boys that were published in various pulp magazines. This World War I story set in the German-infested waters of the Sargasso Sea, where an American crew tries to escape capture and certain death by the hands of the evil enemy. "A potboiler, The Cruise of the Dry Dock is neither in its style nor its choice of subject matter particularly original or impressive." (Martine, 73)

His second novel, Birthright, was first serialized in seven parts in Century Magazine, then collected and published in book form in 1922.[3] This is considered to be Stribling's first serious novel, in which he attempts to "tell the truth" about the negro problem.[4] Birthright was highly praised by critics in both the black and white communities, but it also received mixed reviews.[4] Set in the early 20th century, Birthright is the story of Peter Siner, a young African-American of mixed-race (referred to as mulatto), who has graduated from Harvard and returned to his home town, the fictional Hooker's Bend, Tennessee. He intends to teach in a black school and has hopes of developing a higher level training school, such as Tuskegee or Hampton Institute. He wants to help his race and also heal racial rifts in the village and the South. There he struggles against prejudices of both the white and black man.[5]

His black mother Caroline Siner is a washwoman, and wants him to rise above this place. He indirectly meets his white father for the first time, an older "gentleman", who had helped pay for college, hires him as an assistant to help compile a memoir, and encourages his training school plans. But few others support it, and Peter makes social missteps among both blacks and whites in the small town. Peter finally marries Cissie, a young woman frequently described as an octoroon (meaning she is three-quarters white) and very light with straight hair. She also was educated away from town, but wants to leave, especially after becoming pregnant by a scheming white youth. The couple flee the South, migrating to Chicago, where Peter can take a business job held for him by a Harvard classmate. The Independent found this effort worthy but too bound by stereotypes and the author pushing a theory.[4]

Birthright was a major departure for Stribling from his pulp adventure stories. It is a social critique of not only the discriminatory practices of the South, but in all of America. He notes the social rules, taboos and racial laws of the South that oppressed blacks, such as Jim Crow laws and the Tennessee-initiated Segregation Seating Act for Railroad Cars (1881). Blacks entering the state were required to leave the general cars and move to the segregated car, generally in poorer condition and location on the train.

This novel also reflects ongoing population movements, such as "The Great Migration" of blacks from the mostly rural South to Northern and Midwestern industrial cities. "From 1910 to 1930 between 1.5 million and 2 million African Americans left the South for the industrial cities of the North."[6] The Pennsylvania Railroad hired blacks for construction and to work on its rapidly expanding lines across the country. Many blacks became Pullman workers, considered a good job at the time. World War I had broken out in Europe, and although America had not entered the conflict, it was supplying goods for the war. Northern manufacturers recruited Southern black workers to fill the high demand for factory workers. In addition, blacks voted with their feet, leaving the South to escape Jim Crow laws and racial violence.

During the time that Stribling was writing his adventure stories, he was also traveling extensively, in Europe, and to Cuba and Venezuela. In Venezuela Stribling was inspired to write the novels Fombombo (1923), Red Sand (1924), and Strange Moon (1929). All three are set in Venezuela, and all three explore the country's different social and ethnic classes. He adds a touch of romance and adventure also. All three novels are classified as among the lighter, "fun" reading of Stribling's works.

With Teeftallow (1926) and Brightmetal (1928), Stribling returned to novels set in Middle Tennessee and offering social satire. He became well known for this style. These two novels have some overlap in characters. They explore the problems of the South through the eyes of local whites, both poor and middle class. Neither book gained any high critical praise, but both were well received by the reading community.

Vaiden trilogy

1930 was a highly significant year for Stribling. That year he produced his eleventh novel, The Forge (1931), the first book of a trilogy and social satire following three generations of the Vaiden family. That year he married Lou Ella Kloss, a music teacher and hometown friend. They settled in Clifton, Tennessee.

Set in Florence, Alabama, this trilogy follows the Vaiden family from the Civil War and postwar period of emancipation of slaves, to the post-Reconstruction era in the late nineteenth century, and lastly, to the 1920s. Stribling was one of the most popular writers of his time, and the novels are considered significant in Southern literature:

"Through not great literary art, Stribling's trilogy is, nevertheless, historically significant; for in The Forge, The Store, and Unfinished Cathedral, Stribling introduced a subject matter, themes, plot elements, and character types which parallel and at the same time anticipate those that William Faulkner, who owned copies of this trilogy, would treat in Absalom, Absalom! and in the Snopes trilogy." (Martine, 76)

These three novels represent an ambitious overview of social, political and economic issues encountered in the South by blacks and whites and various social classes among them.

The Forge introduces many of the characters who reappear in the next two novels but does not have a single protagonist. Among these is veteran Miltiades "Milt" Vaiden, who had previously been overseer on a major plantation, although he was son of a poor white blacksmith, Jimmie Vaiden. Col. Milt, as he is known, served as an officer in the Confederacy during the Civil War and returns home to struggle to make a place for himself. Finding work, Vaiden soon also finds a woman who he wants to marry, as a means to reach his dreams. She rejects him, choosing a richer man. Vaiden meets and marries another girl, middle-class Ponny BeShears. While he is not so attracted to her, he learns she will gain a nice inheritance after her father dies. He hopes this will help push him into the mercantile class. The background is based on changes in the post-war era, after slavery is abolished. White Southerners attempt to control the changing social and political landscape of free labor and black enfranchisement, in part through such vigilante groups as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which Vaiden also joins.

Stribling's most famous novel is The Store (1932), the second book in The Vaiden Trilogy. It won a Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1933. It returns to Col. Miltiades "Milt" Vaiden, as he is known by this time in the post-Reconstruction era of the 1880s.[7] He has established himself as a prominent business figure in Florence. The South is developing a new economic and social order, with more businesses and industries, such as textile mills, being established. Throughout the course of novel, Vaiden cultivates a reputation for honesty and square dealing, while he also chooses opportune moments to lie and steal. His successes and failures in the arena of commerce contribute much to the dynamics of the storyline. He becomes a merchant and banker.

Meanwhile, it is revealed that, as a young man, Miltiades had raped Gracie, a mixed-race black girl working for his family. His own father Jimmie Vaiden had forced her enslaved mother into sex, so Gracie is his half-sister. Gracie became pregnant after Militades's assault, and gave birth to a boy she named Toussaint (after a hero of the Haitian Revolution). Her son is three-quarters white by descent.

Gracie never tells Toussaint about his father, nor Vaiden about the boy. Gracie keeps Toussaint with her and tries to get him an education, even under southern limits. She hopes that Toussaint will some day be able to travel North, pass as a white man, and marry a white woman. Toussaint's behavior, and "uppity" attitude in terms of Southern expectations, are a central point of tension throughout the story.

The final book in the trilogy is The Unfinished Cathedral (1934). It is set in Florence in the 1920s at a time of economic boom. The Vaiden family are still main characters. It is a time of the rising white middle class to challenge the long dominance of wealthy landowners and merchants. This period also saw significant changes in the status of Southern women and blacks. The now aged Milt Vaiden is a banker and prominent member of his church, where he supports building a great structure. He plans to be buried there.

He also works to take full advantage of an economic boom stimulated by federal spending under President Herbert Hoover for public works projects. His campaign promises gained new urgency after the stock market crash of 1929. Flood control proposed for the Tennessee River stimulated speculators to acquire land before development took place. As Florence attracts new businesses and residents, Vaiden and others tried to buy land, especially from poor blacks. They had been disenfranchised in the early 20th century, their schools are underfunded, and many are uneducated and left outside the economic boom. Local whites offer sums of money for their land that blacks couldn't refuse, or used threats to run them off, or found other means to cheat them.

In this novel, Stribling moves the trial of the Scottsboro boys to Florence. As he says, he uses it in an incidental way, to show that such a trial could take place in the South. He is most interested in how the various social classes and groups react to it, as well as exploring Northern intervention through activities of the Communist Party, and civil rights groups.[8]

Gracie and her son Toussaint never were able to leave Florence. She is being kept by a white man. Toussaint runs afoul of the law and is lynched with other black men by a white mob.

Meanwhile, the town pastor and Vaiden have gotten caught up in the fever of expansion. The pastor ignores the spiritual needs of the townspeople in favor of promoting Vaiden's goal of building a great church. Vaiden is shocked when his cherished daughter becomes pregnant before she marries, and he realizes the generations have really changed. His world is badly shaken even before a bomb brings down the unfinished cathedral around him.[7]

Reception

J. Donald Adams of the New York Times identified Stribling's strengths and weaknesses as a novelist, while surveying his ambitious Vaiden trilogy. He said that Stribling had "imaginative vigor" and "a distinct narrative sense, a facility in that oldest of story-teller's arts, the awakening of his reader's curiosity as to what will happen next. He has, too, the gift of convincing dialogue."[9] But, Adams said that Stribling lacks feeling for words and his work is unsatisfying in terms of the characters he creates, their experiences do not illuminate life. He also criticizes the writer for relying on coincidence, and falling into melodrama.[9]

In this period of the late 1920s and 1930s, Stribling was among the most popular writers, and also received critical praise. As noted, The Store won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1933. In addition, both the second and third novels of the trilogy were chosen as selections by the Literary Guild, which published their own editions to highlight the honor.[7]

Other novels

Stribling's last two novels are set in the major cities of New York City and Washington, D.C. The Sound Wagon (1935), a political novel set in both cities, explores America's political system and ideals. Like the Vaiden Trilogy, this is a satire. The main character is a young lawyer named Henry Caridius who goes to Washington, D.C. in hopes of making great changes; he fails there. The novel has strong similarities to the plot of Birthright.

These Bars of Flesh (1938), Stribling's last book, is set in New York City. This novel may have been a response to Stribling's having taught English at Columbia University in 1935. The novel is set in a NYC university, where Andrew Barnett from Georgia hopes to attain his degree. Stribling takes a satirical look at campus politics, professor tenure and education, and the extent of the students' lack of awareness.

After this last novel, Stribling continued to write mystery short stories that were published in various magazines. These were eventually collected and published posthumously as The Best of Dr. Poggioli, 1934-1940 (1975).

Adaptations

Stribling's work has been adapted for both film and plays:

- Birthright was twice adapted as a feature film with the same name, both times by noted African-American director Oscar Micheaux. The 1924 version was a silent film. Fifteen years later, Micheaux co-wrote, produced and directed another version, and Birthright was distributed in 1939. The 1924 film is lost and only part of the 1939 Birthright film survives. This remaining portion was restored under the supervision of the Library of Congress.

- Rope. This play was adapted by Stribling with David Wallace from Teeftallow; it was produced at the Biltmore Theatre, on Broadway, New York City (1928)[10]

- The Great Fombombo. This play was adapted by David Wallace from the novel Fombombo; it was produced at the Beachwood Theatre, New York City (1932).

Death and legacy

Stribling and his wife returned in 1959 to live in his hometown of Clifton, Tennessee. During his final months of declining health, the couple stayed in Florence, where he died on July 8, 1965. He is buried in Clifton.

The Stribling home was donated to the city of Clifton in 1946. Following the author's death, the city has operated this residence as the T.S. Stribling Museum, a house museum and library devoted to his life and career. The museum building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as part of Clifton's Water Street Historic District.

Laughing Stock: The Posthumous Autobiography of T.S. Stribling (1982), was compiled from the author's manuscripts by Randy Cross and John T. McMillan, doctoral students at the University of Mississippi. It was published posthumously.

Stribling's private papers are held by the Tennessee State Library and Archives. A copy of his writings and research materials, and some memorabilia, are also found at the Collier Library Archives and Special Collections at the University of North Alabama, his alma mater.

Works

Novels

- The Cruise of the Dry Dock (1917). A children's novel published in a limited edition of 250 copies.

- Birthright (1921). First published as a serial in The Century Magazine from October 1921, then as a novel in 1922. (available free online at Wikisource)

- Fombombo (1922) (available free online @ Google Books,

- Red Sand (1923)

- Teeftallow (1926) (available free online @ Google Books)

- Bright Metal (1928)

- East is East (1922)

- Strange Moon (1929)

- Backwater (1930)

The following three form the Vaiden trilogy:

- The Forge (1931)

- The Store (1932), winner of the 1933 Pulitzer Prize for the Novel

- Unfinished Cathedral (1933)

- The Sound Wagon (1935)

- These Bars of Flesh (1938)

Short story collections

- Clues of the Caribbees: Being Certain Criminal Investigations of Henry Poggioli, Ph. D. (1929)

The following collections were all edited and published posthumously:

- Best Dr. Poggioli Detective Stories (Dover, 1975)

- Dr. Poggioli: Criminologist (Crippen & Landru, 2004)

- Web of the Sun (2012) - also contains "The Green Splotches"

Short fiction

- 'The Father of Invention'. Trotwood Monthly, September 1906

- 'Old Four Toes'. Trotwood Monthly, October 1906

- 'Big Jack'. Great Bend Tribune, 8 May 1908

- 'The Pictures of Jacqueleau'. Illustrated Sunday Magazine, 18 April 1909

- 'The Loot of the Dog Star'. Illustrated Sunday Magazine, 4 July 1909

- 'The Peace Commissioner'. Illustrated Sunday Magazine, 25 July 1909

- 'Romance to Order'. Buffalo Enquirer, 8 December 1909

- 'Seeking the Stolen Service'. Leaonardsville News, 21 July 1910

- 'The Utility Man'. Shelby City Herald, 14 September 1910

- 'Old Block and Chips'. Junction City Republic, 17 December 1910

- 'Getting Action'. The American Boy, February 1915

- 'A Hammerhead Film'. The American Boy, April 1915

Poetry

- Design on Darkness

- The Dead Master. Gastonia Gazette, 11 October 1907

- To a Cherokee Rose. Florence Herald, 21 October 1921

Short non-fiction

- Apology to Florence, Wings Magazine, June 1934. Essay related to his novel The Unfinished Cathedral, before its publication as a Literary Guild selection.

Non-fiction books

- Laughing Stock: The Posthumous Autobiography of T.S. Stribling (1982) This was not Stribling's work, but was compiled from his manuscripts by doctoral students Randy Cross and John T. McMillan at University of Mississippi.

References

- Bain, Robert, comp. and ed. Southern Writers: A Biographical Dictionary. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State Press, 1979. 433.

- Kunitz, Stanley, ed. Twentieth Century Authors: A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Literature. New York: The H. W. Wilson Company, 1942. 1359.

- Martine, James J., ed. Dictionary of Literary Biography: Volume Nine, American Novelist, 1910-1945, Part 3: Mari Sandoz-Stark Young. Detroit, MI: 1981. 72

Notes

- ↑ DeAndrea, William. "Stribling, T(homas) S(igismund)" in Encyclopedia Mysteriosa. MacMillan, 1994 (p. 342).

- ↑ Moskowitz, Sam. "T. S. Stribling, Subliminal Science-Fictionist". Fantasy Commentator, Winter 1989/1990 (pp. 230-243, 277-296).

- ↑ T. S. Stribling, Birthright, New York: The Century Company, 1922

- 1 2 3 Boynton, H. W. (13 May 1922). Book Reviews: Yellow Is Black. Vol. 108. p. 457. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ T. S. Stribling, Birthright, New York: The Century Company, 1922, pp. 1-14, et al.

- ↑ "Great Migration". 2003.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - 1 2 3 "Books: Trilogy Finished". TIME (Magazine). 4 June 1934. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ↑ Stribling, T.S. (June 1934). "An Apology to Florence". Wings. University of North Alabama. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- 1 2 Adams, J. Donald (10 June 1934). "T. S. Stribling Concludes His Trilogy". New York Times. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ↑ "Rope (By D. Wallace) : "A Drama" by David Wallace and T.S. Stribling (Based upon Mr. Stribling's novel, "Teeftallow")". University of Florida. nd. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

External links

- T.S. Stribling Museum

- William E. Smith, Jr., "T. S. Stribling: Southern Literary Maverick", University of North Alabama Collier Library website.

- Thomas Sigismund Stribling at IMDb

- T.S. Stribling at the Internet Broadway Database

- Photos of the first edition of The Store

- Works by T. S. Stribling at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about T. S. Stribling at Internet Archive