A time signal is a visible, audible, mechanical, or electronic signal used as a reference to determine the time of day.

Church bells or voices announcing hours of prayer gave way to automatically operated chimes on public clocks; however, audible signals (even signal guns) have limited range. Busy seaports used a visual signal, the dropping of a ball, to allow mariners to check the chronometers used for navigation. The advent of electrical telegraphs allowed widespread and precise distribution of time signals from central observatories. Railways were among the first customers for time signals, which allowed synchronization of their operations over wide geographic areas. Dedicated radio time signal stations transmit a signal that allows automatic synchronization of clocks, and commercial broadcasters still include time signals in their programming.

Today, global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) radio signals are used to precisely distribute time signals over much of the world. There are many commercially available radio controlled clocks available to accurately indicate the local time, both for business and residential use. Computers often set their time from an Internet atomic clock source. Where this is not available, a locally connected GNSS receiver can precisely set the time using one of several software applications.

Audible and visible time signals

One sort of public time signal is a striking clock. These clocks are only as good as the clockwork that activates them, but they have improved substantially since the first clocks from the 14th century. Until modern times, a public clock such as Big Ben was the only time standard the general public needed.

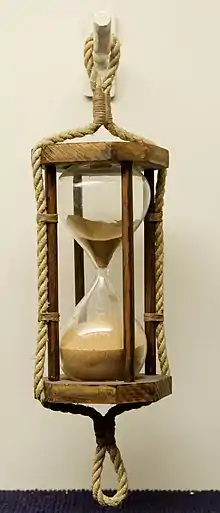

Accurate knowledge of time of day is essential for navigation, and ships carried the most accurate marine chronometers available, although they did not keep perfect time. A number of accurate audible or visible time signals were established in many seaport cities to enable navigators to set their chronometers.

Signal guns

In Vancouver, British Columbia, a "9 O'Clock Gun" is still shot every night at 9 pm. (This gun was brought to Stanley Park in 1894 by the Department of Fisheries originally to warn fishermen of the 6:00 pm Sunday closing of fishing.) The 9:00 pm firing was later established as a time signal for the general population. Until a time gun was installed, the nearby Brockton Point lighthouse keeper detonated a stick of dynamite. Elsewhere in Canada, a "Noon Gun" is fired daily from the citadels in Halifax and Quebec City and from Signal Hill in St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador.[1]

In the same manner, a Noon Gun has been fired in Cape Town, South Africa, since 1806.[2] The gun is fired daily from the Lion Battery at Signal Hill.

The Noonday Gun serves a similar purpose in Hong Kong. The tradition, which started in the 1860s under British colonial rule, has become a tourist attraction in recent times.

A cannon was fired at one o'clock every weekday at Liverpool, England, at the Castle in Edinburgh, Scotland, and also at Perth in Australia to establish the time. The Edinburgh "One O'Clock Gun" is still in operation. A cannon located at the top of Santa Lucia Hill, in Santiago, Chile, is shot every noon.

In Rome, on the Janiculum, a hill west of the Tiber since 1904 a cannon is fired daily at noon towards the river as a time signal. This was introduced in 1847 by Pope Pius IX to synchronise all the church bells of Rome. It was situated in Castel Sant'Angelo until 1903 when it was moved to Monte Mario for a few months until it was placed in its current position. The cannon was silenced from the start of WWII for about twenty years until 21 April 1959, the 2712th anniversary of Rome's founding, and has been in use since then.

For many years an old cannon was fired "about noon" from a mountain near Kabul, Afghanistan.[3][4]

Sirens, whistles, and other audible signals

In many Midwestern US cities where tornadoes are a common hazard, the emergency sirens are tested regularly at a specified time (say, noon each Saturday); while not primarily intended to mark the time, local people often check their watches when they hear this signal. In many non-seafaring communities, loud factory whistles served as public time signals before radio made them obsolete. Sometimes, the tradition of a factory whistle becomes so deeply entrenched in a community that the whistle is maintained long after its original function as a time keeper became obsolete.[5] For example, the University of Iowa's power plant whistle has been reinstated several times by popular demand after numerous attempts to silence it.[6]

Visual signals

In 1861 and 1862, the Edinburgh Post Office Directory published time gun maps relating the number of seconds required for the report of the time gun to reach various locations in the city. Because light travels much faster than sound, visible signals enabled greater precision than audible ones, although audible signals could operate better under conditions of reduced visibility. The first time ball was erected at Portsmouth, England in 1829 by its inventor Robert Wauchope.[7] One was installed in 1833 on the roof of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, and the time ball has dropped at 1:00 pm every day since then.[8] The first American time ball went into service in 1845.[7] In New York City, the ceremonial Times Square Ball drop on New Year's Eve in Times Square is a vestige of a visual time signal.

Electrical time signals

United Kingdom

The first telegraph distribution of time signal in the United Kingdom, indeed, in the world, was initiated in 1852 by the Electric Telegraph Company in collaboration with the Astronomer Royal. Greenwich Mean Time was distributed by telegraph from the Greenwich Observatory. This included a system for synchronising the drop of the time ball at Greenwich with other time balls around the country, one of which was atop the Electric's offices in the Strand.[9]

Other synchronised time balls were atop the Nelson Monument, Edinburgh; the sailors' home Broomielaw, Glasgow; Liverpool and one at Deal, Kent, installed by the Admiralty.[9]

United States

Telegraph signals were used regularly for time coordination by the United States Naval Observatory starting in 1865.[10] By the late 1800s, many U.S. observatories were selling accurate time by offering a regional time signal service.[11]

Sandford Fleming proposed a single 24-hour clock for the entire world. At a meeting of the Royal Canadian Institute on 8 February 1879 he linked it to the anti-meridian of Greenwich (now 180°). He suggested that standard time zones could be used locally, but they were subordinate to his single world time.

Standard time came into existence in the United States on 18 November 1883. Earlier, on 11 October 1883, the General Time Convention, forerunner to the American Railway Association, approved a plan that divided the United States into several time zones. On that November day, the US Naval Observatory telegraphed a signal that coordinated noon at Eastern standard time with 11 am Central, 10 am Mountain, and 9 am Pacific standard time.

A March 1905 issue of The Technical World describes the role of the United States Naval Observatory as a source of time signals:

- One of the most important functions of the Naval Observatory is found in the daily distribution of the correct time to every portion of the United States. This is effected by means of telegraphic signals, which are sent out from Washington at noon daily, except Sundays. The original object of this time service was to furnish mariners in the seaboard cities with the means of regulating their chronometers; but, like many another governmental activity, its scope has gradually broadened until it has become of general usefulness. The electrical impulse which goes forth from the Observatory at noon each day, now sets or regulates automatically more than 70,000 clocks located in all parts of the United States, and also serves, in each of the larger cities of the country, to release a time-ball located on some lofty building of central location. The dropping of the time-ball – accompanied, at some points, with the simultaneous firing of a cannon – is the signal for the regulation by hand of hundreds of other clocks and watches in the vicinity.

Radio time sources

Dedicated time signal broadcasts

The telegraphic distribution of time signals was made obsolete by the use of AM, FM, shortwave radio, Internet Network Time Protocol servers as well as atomic clocks in satellite navigation systems. Time signals have been transmitted by radio since 1905.[12] There are dedicated radio time signal stations around the world.

Time stations operating in the longwave radio band have highly predictable radio propagation characteristics, which gives low uncertainty in the received time signals. Stations operating in the shortwave band can cover wider areas with relatively low-power transmitters, but the varying distance that the signal travels increases the uncertainty of the time signal on a scale of milliseconds.[13]

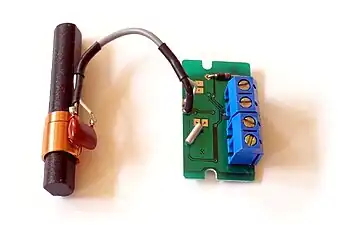

Radio time signal stations broadcast the time in both audible and machine-readable time code form that can be used as references for radio clocks and radio-controlled watches. Typically, they use a national or regional longwave digital signal; for example, station WWVB in the U.S. .[13]

The audio portions of the shortwave WWV and WWVH broadcasts can also be heard by telephone. The time announcements are normally delayed by less than 30 ms when using land lines from within the continental United States, and the stability (delay variation) is generally less than 1 ms. However, when mobile phones are used, the delays are often more than 100 ms, due to the multiple access methods used to share cell channels. In rare instances when the telephone connection is made by satellite, the time is delayed by 250–500 ms.

The audio from the broadcasts is available by telephone by dialling U.S. numbers (303) 499-7111 for WWV (Colorado), and (808) 335-4363 for WWVH (Hawaii). Calls (which are not toll-free) are disconnected after 2 minutes.

Loran-C time signals formerly were also used for radio clock synchronization, by augmenting their highly accurate frequency transmissions with external measurements of the offsets of LORAN navigation signals against time standards.

General broadcasters

As radio receivers became more widely available, broadcasters included time information in the form of voice announcements or automated tones to accurately indicate the hour. The BBC has included time "pips" in its broadcasts from 1922.[12]

In the United States many information-based radio stations (full-service, all-news and news/talk) also broadcast time signals at the beginning of the hour. In New York, WCBS and WINS have distinctive beginning-of-the-hour tones, though the WINS signal is only approximate (several seconds error). WINS also has a tone at 30 minutes past the hour for those setting their clocks. WTIC uses the Morse code V for victory to the tune of Beethoven's 5th Symphony at the beginning of the hour continuously, since 1943.

Broadcast stations using iBiquity Digital's "HD Radio" system are contractually required[14] to delay their analog broadcast by about eight seconds, so it remains in sync with the digital stream. Thus, network-generated time signals and service cues will also be delayed by about eight seconds. (Because of the delay, when WBEN-AM in Buffalo, New York was broadcasting time markers, and was simulcast on an FM station that broadcast in HD; the FM signal did not carry the time signal. WBEN does not broadcast in HD.) Local signals may also be delayed.

The all-news radio stations of the CBS Radio Network, of which WCBS is the flagship, air a "bong" (at a frequency of 440 Hz – the international standard for the musical note A ) that immediately precedes each top-of-the-hour network newscast. (The same bong could be heard on the CBS Television Network, at the top of the hour immediately before the beginning of any televised program, in the 1960s and 1970s.) An automated "chirp" at one second before the hour signals a switch to the radio network broadcast. As an example, KNX, the CBS Radio Network all-news station in Los Angeles, broadcasts this "bong" sound on the hour. However, due to buffering of the digital broadcast on some computers, this signal may be delayed as much as 20 seconds from the actual start of the hour (this is presumably the same situation for all CBS Radio stations, as each station's digital stream is produced and distributed in a similar manner), though unlike program content which is on a broadcast delay for content concerns, the time signal airs as-is over-the-air, meaning it can sometimes be talked over during a live news event or sports play-by-play. KYW-AM in Philadelphia broadcasts a time signal at the top of the hour along with its jingle.

Bonneville International-owned news/talk station KSL (AM-FM) in Salt Lake City uses a "clang" that originates from the Nauvoo Bell on Temple Square, in Salt Lake City, which has been a staple on the station since the early 1960s.

In Canada, the national English-language non-commercial CBC Radio One network broadcast the daily National Research Council Time Signal from 5 November 1939[15] until 9 October 2023.[16] The simulcast would occur daily at 1pm Eastern Time. Its French-language counterpart, Radio-Canada, broadcasts a similar signal at noon. Vancouver radio station CKNW also broadcasts time signals, using a chime every half-hour. Time signals on CBC broadcasts may be delayed up to 3 seconds due to network processing delays between the local radio transmitter and the time signal origin in Ottawa. The CBC's predecessor, the Canadian National Railways Radio network, broadcast the time signal over its Ottawa station, CNRO (originally CKCH), at 9 pm daily and also on its Moncton station, CNRA, beginning in 1923. CNRA closed in 1931 but the broadcasts continued on CNRO when the station was acquired by the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission in 1933 and by the CBC in 1936 before going national in 1939.[17]

In Australia, many information-based radio stations broadcast time signals at the beginning of the hour, and a speaking clock service was also available until October 2019. However, the VNG dedicated time signal service has been discontinued.[18]

In Cuba, Radio Reloj is a radio station which has a time signal over news. Radio Reloj translates to Clock Radio.

Digital delay

Program material, including time signals, that is transmitted digitally (e.g. DAB, Internet radio) can be delayed by tens of seconds due to buffering and error correction, making time signals received on a digital radio unreliable when accuracy is needed.

See also

- American Practical Navigator

- Car radio, Radio Data System (RDS)

- Clock signal

- Extended Data Services and PBS

- Global Positioning System § Timekeeping

- Greenwich Time Signal

- Low frequency, (LF)

- Smart Personal Objects Technology, (SPOT)

- Speaking clock

- Synchronization

- VBI, VITC

- WWVB

- Time synchronization in North America

- Time transfer

- Time and frequency transfer

- Time synchronization

References

- ↑ Parks Canada Agency, Government of Canada (10 April 2019). "Noon Day Gun - Signal Hill National Historic Site". www.pc.gc.ca.

- ↑ "Noon Gun -". bokaap.co.za. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ↑ "The noon gun". Christian Science Monitor. 22 April 1982. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ↑ "The Old Noon Day Gun of Kabul - Afghanistan". digitalsilver.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ↑ Ross, Jenna (9 April 2015). "Midwestern towns with sirens weigh nostalgia against nuisance". Minneapolis Star Tribune. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ Snee, Tom (18 April 2011). "The enduring exhalations of The Whistle". Iowa Now. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- 1 2 Aubin, David The Heavens on Earth: Observatories and Astronomy in Nineteenth-Century Science and Culture p.164. Duke University Press, 2010

- ↑ "Greenwich Time Ball". greenwichmeantime.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 October 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- 1 2 Kieve, Jeffrey L., The Electric Telegraph: A Social and Economic History, pp. 52-53, David and Charles, 1973 OCLC 655205099.

- ↑ "Timekeeping at the U.S. Naval Observatory". Archived from the original on 19 December 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- ↑ Bartky, Ian R. (2000). Selling the true time. Stanford University Press. p. 199. ISBN 9780804738743. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- 1 2 Burns, R.W. (2004). Communications: An international history of the formative years. IET. p. 121. ISBN 0863413277.

- 1 2 McCarthy, Dennis D.; Seidelmann, P. Kenneth (2009). Time: From Earth rotation to atomic physics. Wiley-VCH. p. 256. ISBN 3-527-40780-4.

- ↑ Licensing fact sheet 2009 (PDF) (Report). iBiquity Digital Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2011 – via ibiquity.com.

- ↑ Bartlett, Geoff (5 November 2014). "'The beginning of the long dash' indicates 75 years of official time on CBC". CBC News (cbc.ca). Retrieved 8 April 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Taekema, Dan (10 October 2023). "The end of the long dash: CBC stops broadcasting official 1 P.M. time signal". CBC News (cbc.ca). Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ↑ "The beginning of the long dash". CBC News (cbc.ca). CBC Archives. 1939. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Kruijshoop, Alfred; Walker, Marjorie. "Introduction". Time NZ & A (Report). Retrieved 23 November 2013 – via tufi.alphalink.com.au.

{{cite report}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Further reading

- Downing, Michael (2005). Spring Forward: The annual madness of Daylight Saving Time. Shoemaker and Hoard. ISBN 1-59376-053-1.

External links

- "The Time Ball and the One O'clock Gun". Liverpool, UK: Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory. 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- "Perth". Travel in Western Australia. Travel Downunder. Archived from the original on 2 July 2005. — mentions the time cannon at Perth

- "Noon Gun". Durr Cannon / Research Projects. museums.org.za. South Africa. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. — mentions the time cannon at Cape Town

- "The VNG User's Consortium". tufi.alphalink.com.au. Australia. — The VNG Users' Consortium was working on ways to solve the problem of the lack of accurate time signals in Australia.

- "The Edinburgh time gun". edinphoto.org.uk. Scotland.

- Fawcett, Waldon (March 1905). "Distribution of time signals". The Technical World. Vol. 3, no. 1. pp. 19–26. OCLC 9990027. Retrieved 2 January 2024 – via babel.hathitrust.org.

Many-sided activities of the U.S. Naval Observatory at Washington, DC – the determination of time and other important astronomical work.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

-

- Magazine was published from 1904–1905 by the Armour Institute of Technology.

- "Distributed time service: An upgrade to current time station technology". hireme.geek.nz. New Zealand.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Hacko, Nick, VK2DX. "Receiving, identifying and decoding time signals". GenesisRadio.com.au. Australia.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link)

.png.webp)