Traditional Chinese bookbinding, also called stitched binding (Chinese: 線裝 xian zhuang), is the method of bookbinding that the Chinese, Koreans, Japanese, and Vietnamese used before adopting the modern codex form.[1]

History

Bound scroll

Up until the 9th century during the mid-Tang dynasty, most Chinese books were bound scrolls made of materials such as bamboo, wood, silk, or paper. Originally bamboo and wooden tablets were tied together with silk and hemp cords to fold onto each other like an accordion. Silk and paper gradually replaced bamboo and wood. Some books were not rolled up but pleated and called zhe ben, although this was still one long piece of material.[2]

Butterfly binding, whirlwind binding and others

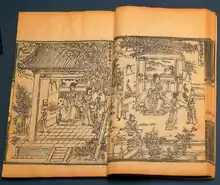

During the 9th and 10th centuries, bound scrolls were gradually replaced by a new book format known as "butterfly binding" (經摺裝, also see Orihon), from the late Tang period onward.[3] This change is tied to the rise of Buddhism and woodblock printing. The accordion-fold books were easier to handle than bound scrolls while reading and reciting sutras. The advantage was that it was now possible to flip to a reference without unfolding the entire document. Woodblock prints also made the new format easier by allowing two mirror images to be easily replicated on a single sheet. Thus two pages were printed on a sheet, which was then folded inwards. The sheets were then pasted together at the fold to make a codex with alternate openings of printed and blank pairs of pages. In the 14th century, the folding was reversed outwards to give continuous printed pages, each backed by a blank hidden page. This development, known as wrapped-back binding (baobei zhuang 包背裝), was used during the Southern Song dynasty and the Ming dynasty; it improved upon the butterfly binding by folding pages the opposite way.[4] The next development known as "whirlwind binding" (xuanfeng zhuang 旋風裝) was to secure the first and last leaves to a single large sheet, so that the book could be opened like an accordion.[5] During the 16th and 17th centuries, pasted bindings were replaced by stitched "thread bindings".[6] Also known as side-stitched binding (xian zhuang 線裝), this type of binding was the final phase of traditional bookbinding in East Asia.[4]

Materials

The paper used as the leaves is usually xuan paper (宣紙). This is an absorbent paper used in traditional Chinese calligraphy and painting. Stronger and better quality papers may be used for more detailed works that involve multicoloured woodblock printing. The covers tend to be a stronger type of paper which is dyed dark blue. Yellow silk can be used and it is more common in works funded by the ruler. The cover is then backed by normal xuan paper to strengthen it. Hardcovers are rare and only used in very important books. The silk cord is almost always white. The case for the books is usually made of wood or bookboard, covered with cloth or silk. The book's inside is covered in paper.

Method

The method of this binding is in several stages:

- The first stage is to fold the printed paper sheets. The printing method was to print on a large sheet, then fold it in half so the text appears on both sides.

- The second stage is to gather all the folded leaves into order and assemble the back and front covers. Important or luxury edition books have a further single leaf inserted in the fold of the leaves. Front covers tend to be replaced over time if it gets damaged. For very old books, the front cover is usually not original; for facsimiles, it is most certainly not.

- The third stage is to punch holes at the spine edge, around 1 cm from the spine. Four holes are the standard. In China, six holes may be used on important books. If the book is a quality edition, the edges of the spine side are wrapped in silk which is stuck on to protect the edges. In Korea, an odd number of holes is normally used, typically three or five.

- The fourth stage is to stitch the whole book together using a thin double silk cord. The knot is tied and concealed in the spine.

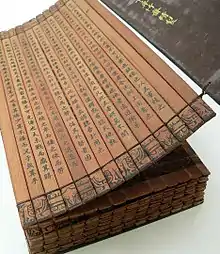

Encasement

After a group of books are printed, they are often put in a case. This is a cloth case that is constructed from boards that have a cloth upholstering. Traditional cloth cases are a single line of boards attached together and covered by the cloth; the insides are papered. The pile of books are placed in the middle board, and the left-hand boards wrap the left side and the front of the books, and the right boards wrap the right side and on top of the left side boards. The right side front board has the title tag pasted on the top right-hand side. The rightmost edge has a lip, from which two straps with ivory or bone tallies are connected to. These straps are pulled down the left side, where there are the loops where they are inserted to secure the whole case together.

Modern cases are much like Western ones. They are basically cuboid with an opening in one side where the books slot in. The Chinese have a separate board to wrap the books before inserting into the case.

References

- ↑ Chinnery, Colin (July 2, 2007). "Bookbinding". International Dunhuang Project. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- ↑ Tsien 1985, p. 227.

- ↑ Tsien 1985, p. 231.

- 1 2 Song, Minah (2009). "The history and characteristics of traditional Korean books and bookbinding". Journal of the Institute of Conservation. 32 (1): 62. doi:10.1080/19455220802630743. ISSN 1945-5224.

- ↑ Wilkinson 2012, p. 912.

- ↑ "Dunhuang concertina binding findings". Archived from the original on March 9, 2000.

Literature

- Kosanjin Ikegami: Japanese Bookbinding: Instructions from a Master Craftsman. Weatherhill, 1986. ISBN 978-0-8348-0196-7

- Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985), Paper and Printing, Needham, Joseph Science and Civilization in China:, vol. 5 part 1, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-08690-6

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012), Chinese History: A New Manual, Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute

External links

- K.T. Wu 吳光清, The Chinese Book: Its Evolution and Development T'ien Hsia Monthly, Vol.III, No.I, August 1936, pp.25-33.

- Japanese bookbinding

- Vietnamese bookbinding

- The Herbert Offen Research Collection of the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum

- A video lesson in Chinese wrapped-back binding (pt. 1)

- A video lesson in Chinese wrapped-back binding (pt. 2)