Unarpur | |

|---|---|

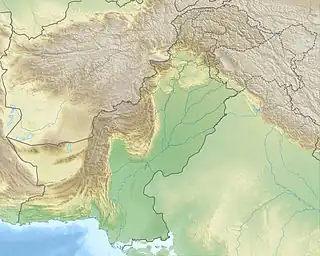

Unarpur Location in Sindh  Unarpur Unarpur (Pakistan) | |

| Coordinates: 25°38′36″N 68°21′21″E / 25.643352°N 68.355715°E[1] | |

| Country | Pakistan |

| Region | Sindh |

| District | Jamshoro |

| Taluka | Manjhand |

| Population (2017)[2] | |

| • Total | 4,092 |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+6 (PDT) |

Unarpur is a village and deh in Manjhand taluka of Jamshoro District, Sindh.[3] It is located close to the west bank of the Indus river, across from Matiari, on the main road from Kotri to Sehwan.[4] As of 2017, Unarpur has a population of 4,092, in 891 households.[2] It is the seat of a tappedar circle, which also includes the villages of Belo Unerpur, Budhapur, Nai Jetharo, and Wachero.[2]

Unarpur has a significant forested area, which was planted by the Talpur Mirs during the 1780s for the purpose of hunting.[4] Once one of the largest forests in Sindh,[4] it has since been severely deforested as the trees standing on some 10,000 acres of land were cut down to clear kachha land for cultivation.[5]

History

During the Mughal era, Unarpur was the seat of a pargana in the sarkar of Chakar Hala.[6] Its dependencies included the villages of Khasa'i Shura and Budhapur.[6]

In April-June 1592, Unarpur[note 1] was the site of a siege between Mirza Jani Beg, the rebellious governor of Thatta, and Abdul Rahim Khan-i-Khanan, representing the Mughal forces loyal to Akbar.[6] After being defeated in battle near the Lakki pass on 11 April, Mirza Jani Beg sailed downstream to Unarpur, where he set up a makeshift fort: the sails of the boats he had sailed here on were converted into sacks and filled with sand, which were then stacked on top of each other to form battlements.[6] A large moat, both deep and wide, was dug around the whole thing.[6] The Khan-i-Khanan arrived on 15 April and laid siege to the Mirza's makeshift fort.[6]

Although the Mirza's forces were numerically stronger, their morale was soon sapped by news of imperial victories elsewhere in the region.[6] Later they ran out of supplies and were forced to eat their own animals to avoid starvation.[6] The Mirza's son and father also both died during the siege, causing him personal distress.[6] Meanwhile, disease broke out in the Khan-i-Khanan's camp.[6] In an attempt to bring the siege to an end, the besieging army prepared to storm the fort from all sides: they dug tunnels, filled the moat, and put up mounds of sand; but the Mirza's troops undid all these attempts and made the whole effort useless.[6]

At last, with the rainy season fast approaching and both sides' troops suffering, the Mirza and Khan-i-Khanan exchanged emissaries to discuss a peaceful agreement to end the siege.[6] [note 2][6] After some negotiations, Mirza Jani Beg formally surrendered on 16 June and the Unarpur "fort" was dismantled.[6]

Around 1874, Unarpur's population was estimated at 1,633 people, including 1,281 Muslims (mostly Shoras) and 352 Hindus (mostly Lohanos).[4] Most residents worked in agriculture.[4] Although not a significant industrial centre, Unarpur did have "a small local trade in grain, ghi and oil."[4] It was the seat of a tappedar and had a school, dharamshala, and small police thana.[4] Part of the road between Unarpur and Petaro was washed away by the Indus in 1869.[4]

Notes

References

- ↑ "Geonames Search". Do a radial search using these coordinates here.

- 1 2 3 Population and household detail from block to tehsil level (Jamshoro District) (PDF). 2017. pp. 11–2. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ↑ "List of Dehs in Sindh" (PDF). Sindh Zameen. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hughes, A.W. (1874). A Gazetteer of the Province of Sindh. London: George Bell and Sons. pp. 12, 335, 507, 695, 869. Retrieved 25 December 2021.

- ↑ Ram, Nanik (2010). "An Analysis of Rural Poverty Trends in Sindh Province of Pakistan". Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences. 4 (6): 1404. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Akhtar, Muhammad Saleem (1983). Shāhjahānī of Yūsuf Mīrak (1044/1634) Sind under the Mughuls: an introduction to, translation of and commentary on the Maẓhar-i Shāhjahānī of Yūsuf Mīrak (1044/1634). pp. 108–113, 255–6. Retrieved 28 December 2021.