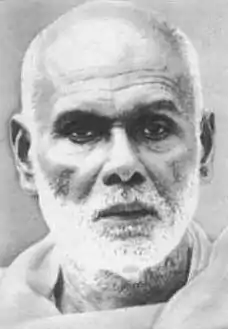

Vagbhatananda | |

|---|---|

| Born | Vayaleri Kunhikkannan Gurukkal April 27, 1885 Kuthuparamba, Kerala |

| Died | October 29, 1939 (aged 54) |

| Known for | Spiritual guru, social reformer |

Vayaleri kunhikannan Gurukkal-(Vagbhatananda) (1885 – October 1939) was a Hindu religious leader and Reform movement in British India. He was the founder of the Atmavidya Sangham, which was fundamentally a group of professionals and intellectuals who sought change, and also the Uralungal Labour Contract Co-Operative Society.[1]

Biography

Vagbatananda was Born in 1885 near Kuthuparamba in a Ezhava family, V. K. Gurukkal undertook his studies under M. K. Gurukkal and Parampath Rairu Nair in the traditional pattern of guru- kula education. According to K.K.N Kurup, "He gained proficiency in scriptures, six systems of Philosophy, logic and other sästras. Then he travelled extensively and propagated the teachings of universal non-duality for a better and egalitarian society. He started Sanskrit School in Calicut and simultaneously took great interest in the activities of Brahma Samaj in that urban centre. This organisation known as Atmavidya Sangham, founded in 1920 by Vagbhatananda had been a major force of social change in Malabar. Like Narayanaguru, Vagbhatananda was also an eminent philosopher who followed the path of Advaita of Sankara.[2]

Vagbhatananda, who was married, died in October 1939. Kurup has described him as a "good combination of an erudite scholar, reformer, organiser, journalist and nationalist. ... His authority was the ancient wisdom of Hinduism, not the dogmatism of theology." [3] The significance of the Atmavidya Sangham declined after his death, being superseded by other secular-oriented reform groups such as the Karshaka Sangham that adopted its agenda. However, it was still active in the 1980s".[4]

Movement

Some time after 1898, Vagbhatananda founded a school to teach Sanskrit in Kozhikode, and also took interest in the work of the Brahmo Samaj that had been founded there that year by Ayyathan Gopalan.[2]

In 1920, Vagbhatananda founded the Atmavidya Sangham, whose principles he outlined in an Advaita treatise titled Atmavidya.[2]K.K.N.Kurup says' "Unlike the Sree Narayana Trust (SNT), which had been established by Narayana Guru, which was significant around the same time, the Atmavidya Sangham consisted mostly of professionals and intellectuals and had a secular approach towards reform.[4] It was instrumental in advancing the development of class organisations among peasants of the region, spreading Marxist–Leninist ideas as a counter to the overbearing feudal and religiously orthodox establishment. Vagbhatananda himself criticised both economic exploitation and the role of foreign governments in supporting it.[5]

Vagbhatananda inspired the formation of Uralungal Labor Contract Co-Operative Society in 1925.[6]

Work

According to Kurup,"Modern Kerala Karshaka Sangham incorporated the programme like inter-caste dining and stood against caste formalities and untouchability. However, Atmavidya Sangham even at present exists with some activities in Kerala. E. M. S. Namboodiripad has assessed the role of Vagbhatananda in these words: Though he could not obtain a universal name or fame like Narayana Guru Swami, Vagbhatananda Gurudeva, born in Kottayam taluk of North Malabar, was one who had greatly contributed to the growth of society.[4] He, even superior in his scholarship and eloquence, to Narayanaguru, first cooperated with the Brahmasamaj and later through his own independent organisation of Atmavidya Sangham initiated programme against casteism, consumption of liquor, etc. and even made a few high caste members as his disciples. No doubt, that he had a significant role in the growth of society in North Malabar." It is a matter of great academic interest for historians and sociologists to trace causes responsible for the decline of a progressive movement like this".[4]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ "Execution Team". Shepherds' Chalet. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Kurup (1988), p. 94

- ↑ Kurup (1988), pp. 94, 97

- 1 2 3 4 Kurup (1988), pp. 98–99

- ↑ Kurup (1988), p. 97

- ↑ Isaac & Williams 2017, p. .

Bibliography

- Isaac, T. M. Thomas; Williams, Michelle (2017). Building alternatives : the story of India's oldest construction workers' cooperative. New Delhi, India: LeftWord. ISBN 978-93-80118-46-8. OCLC 1018245138.

- Kurup, K. K. N. (1988), Modern Kerala: Studies in Social and Agrarian Relations, Mittal Publications, ISBN 9788170990949

Further reading

- Kurup, K. K. N. (September 1988). "Peasantry and the Anti-Imperialist Struggles in Kerala". Social Scientist. 16 (9): 35–45. doi:10.2307/3517171. JSTOR 3517171.