Valeriano Weyler | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor-General of Cuba | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 11 February 1896 – 31 October 1897[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Alfonso XIII | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Sabas Marín y González | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Ramón Blanco y Erenas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor-General of the Philippines | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 5 June 1888 – 17 November 1891 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Alfonso XIII | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Emilio Terrero y Perinat | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Eulogio Despujol y Dusay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau 17 September 1838 Palma de Mallorca, Balearic Islands, Spain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 20 October 1930 (aged 92) Madrid, Spain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Liberal Party | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

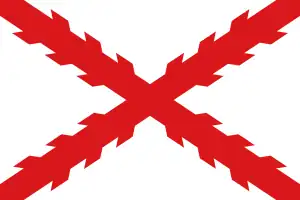

| Allegiance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Commands | 6th Army Corps | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wars | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, 1st Duke of Rubí, 1st Marquess of Tenerife (17 September 1838 – 20 October 1930) was a Spanish general and colonial administrator who served as the Governor-General of the Philippines and Cuba,[2] and later as Spanish Minister for War.

Early life and career

Weyler was born in 1838 in Palma de Mallorca, Spain. His distant paternal ancestors were originally Prussians and served in the Spanish army for several generations.[3] He was educated in his place of birth and in Granada.[4] Weyler decided to enter the Spanish army, being influenced by his father, a military doctor.

He graduated from the Infantry School of Toledo at the age of 16.[4] At 20, Weyler had achieved the rank of lieutenant,[4] and he was appointed the rank of captain in 1861.[5] In 1863, he was transferred to Cuba, and his participation in the campaign of Santo Domingo earned him the Laureate Cross of Saint Ferdinand.[5] During the Ten Years' War that was fought between 1868 and 1878, he served as a colonel[5] under General Arsenio Martínez Campos, but he returned to Spain before the end of the war to fight against Carlists in the Third Carlist War in 1873.[2] In 1878, he was made general.[4]

Canary Islands and Philippines

From 1878 to 1883, Weyler served as Captain-General of Canary Islands. In 1888, Weyler was made Governor-General of the Philippines.[2] Weyler granted the petitions of 20 young women of Malolos, Bulacan, to receive education and to have a night school. The women became known as the Women of Malolos. The original petition was denied by the parish priest of Malolos, who argued that women should always stay at home and take care of the family.

Weyler happened to visit Malolos afterward and granted the petition on account of the persistence the women displayed for their petition. José Rizal wrote a letter to the women, upon request by Marcelo H. del Pilar, praising their initiative and sensibility on their high hopes for women's education and progress. In 1895, he earned the Grand Cross of Maria Christina for his command of troops in the Philippines[2] in which he fought an uprising of Tagalogs[6] and conducted an offensive against the Moros in Mindanao.

Spain

On his return to Spain in 1892, he was appointed to command the 6th Army Corps in the Basque Provinces and Navarre, where he soon quelled agitations. He was then made captain-general at Barcelona, where he remained until January 1896. In Catalonia, with a state of siege, he made himself the terror of the anarchists and communists.[3]

Cuba

After Arsenio Martínez Campos had failed to pacify the Cuban Rebellion, the Conservative government of Antonio Cánovas del Castillo sent Weyler out to replace him. That met the approval of most Spaniards, who thought him the proper man to crush the rebellion.[3]

He was made Governor-General of Cuba with full powers to suppress the insurgency (rebellion was widespread in Cuba) and restore the island to political order and its sugar production to greater profitability. Initially, Weyler was greatly frustrated by the same factors that had made victory difficult for all generals of traditional standing armies fighting against an insurgency.

While the Spanish troops marched in regulation and required substantial supplies, their opponents practiced hit-and-run tactics, lived off the land, and blended in with the noncombatant population. He came to the same conclusions as his predecessors as well: to win Cuba back for Spain, he would have to separate the rebels from the civilians by confining the latter to towns and forts protected by loyal Spanish troops. By the end of 1897, General Weyler had divided the long island of Cuba into different sectors and forced more than 300,000 men, women and children into areas nearby cities. By emptying the land of a sympathetic population, and then burning crops, preventing their replanting, and driving away livestock, the Spanish military made the countryside inhospitable to the insurgents.

Weyler's reconcentrado policy made his military objectives easier to accomplish, but it had devastating humanitarian and political consequences. The reconcentrados, separated from their livelihoods in the countryside and poorly housed at close quarters in the tropical climate, suffered greatly from starvation and disease. Death toll estimates range from 150,000 to 400,000 people.[7][8] Much was made of their suffering in the American press where Weyler became known as "The Butcher".[9] The wave of negative publicity contributed to an atmosphere conducive to the U.S. declaration of war against Spain two months after the sinking of the USS Maine in 1898. The Spanish Conservative government supported Weyler's tactics wholeheartedly, but the Liberals denounced them vigorously for their toll on the Cuban people.

Similar civilian internment policies were applied in the Second Boer War concentration camps by the British (1900–1902),[7] the United States during the Philippine–American War (1899–1902),[7][10] Germany against the Herero (1904–1907) and later by other governments.[7]

The term reconcentrado is thought to have given rise to the term concentration camp, or in German Konzentrationslager, used during World War II and later to describe detention facilities used by the 20th-century regimes of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin. Expert Andrea Pitzer considers these to be the world's first concentration camps.[11]

Weyler's strategy was successful only in alienating the Cuban populace from Spain completely, as well as galvanizing global opinion against Spain. When Spanish Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo was assassinated in June 1897 and a new Liberal ministry took over, Weyler was recalled from Cuba and replaced by the more conciliatory General Ramón Blanco y Erenas.

Return to Spain

He served as Minister of War three separate times (1901–1902, 1905, 1906–1907)[4] and as Chief of Staff of the Army in two separate terms (1916–1922, 1923–1925).

After his return to Spain, Weyler's reputation as a strong and ambitious soldier made him one of those who, in case of any constitutional disturbance, might be expected to play an important role, and his political position was nationally affected by this consideration; his appointment in 1900 as captain-general of Madrid resulted indeed in great success in the defense of the constitutional order. He was minister of war for a short time at the end of 1901, and again in 1905. At the end of October 1909, he was appointed captain-general at Barcelona, where the disturbances connected with the execution of Francisco Ferrer were quelled by him without bloodshed.[3]

Valeriano Weyler, the Marquess of Tenerife, was made Duke of Rubí and Grandee of Spain by royal decree in 1920.[12]

He was charged and imprisoned for opposing the military dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera in the 1920s. He died in Madrid on 20 October 1930. He was buried the next day in a simple casket without state ceremony, as he himself requested.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Austin, Heather. "The Spanish–American War Centennial Website: Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau". Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Weyler y Nicolau, Valeriano". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 567.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "General Valeriano Weyler, Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Valeriano Weyler and Nicolau". Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ↑ "Valeriano Weyler Papers". Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Pitzer, Andrea (2 November 2017). "Concentration Camps Existed Long Before Auschwitz". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ↑ "February, 1896: Reconcentration Policy". PBS. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ↑ "The Butcher of Cuba", "The Salt Lake Tribune", April 5, 1898

- ↑ Storey, Moorfield; Codman, Julian (1902). Secretary Root's record. "Marked severities" in Philippine warfare. An analysis of the law and facts bearing on the action and utterances of President Roosevelt and Secretary Root. Boston: George H. Ellis Company. pp. 89–95. The author compares McKinley's appalled answer to Cuban camps with Root's justification of Philippine camps.

- ↑ "On anniversary of Auschwitz liberation, writer calls attention to modern-day concentration camps". The Current. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 27 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ↑ Gaceta de Madrid no. 190, 8 July 1920, p. 98

Sources

- Navarro García, L. (1998). "1898, la incierta victoria de Cuba". Anuario de Estudios Americanos. University of Sevilla. 55 (1): 165–187. doi:10.3989/aeamer.1998.v55.i1.370.

.svg.png.webp)