In historical linguistics, the wave model or wave theory (German Wellentheorie) is a model of language change in which a new language feature (innovation) or a new combination of language features spreads from its region of origin, affecting a gradually expanding cluster of dialects. Dialect diffusion spreads from a given point of contact like waves on the water.[1]

The theory was intended as a substitute for the tree model, which did not seem to be able to explain the existence of some features, especially in the Germanic languages, by descent from a proto-language. At its most ambitious, it is a wholesale replacement for the tree model of languages.[2] During the 20th century, the wave model had little acceptance as a model for language change overall, except for certain cases, such as the study of dialect continua and areal phenomena; it has recently gained more popularity among historical linguists, due to the shortcomings of the tree model.[2][3]

Principles

The tree model requires languages to evolve exclusively through social splitting and linguistic divergence. In the “tree” scenario, the adoption of certain innovations by a group of dialects should result immediately in their loss of contact with other related dialects: this is the only way to explain the nested organisation of subgroups imposed by the tree structure.

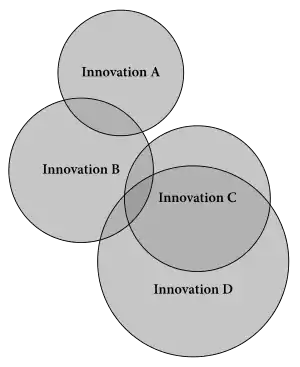

Such a requirement is absent from the Wave Model, which can easily accommodate a distribution of innovations in intersected patterns. Such a configuration is typical of dialect continua (and of linkages, see below), that is, historical situations in which dialects share innovations with different neighbours simultaneously, in such a way that the genealogical subgroups they define form an intersected pattern. This explains the popularity of the Wave model in studies of dialectology.[1]

Johannes Schmidt used a second metaphor to explain the formation of a language from a continuum. The continuum is at first like a smooth, sloping line. Speakers in close proximity tend to unify their speech, creating a stepped line out of the sloped line. These steps are the dialects. Over the course of time, some steps become weak and fall into disuse, while others preempt the entire continuum. As an example, Schmidt used Standard German, which was defined to conform to some dialects and then spread throughout Germany, replacing the local dialects in many cases.

Legacy

In modern linguistics, the wave model has contributed greatly to improve, but not supersede, the tree model approach of the comparative method.[4] Some scholars have even proposed that the wave model does not complement the tree model but should replace it for the representation of language genealogy.[2] The recent works have also focused on the notion of a linkage,[5] a family of languages descended from a former dialect continuum; linkages cannot be represented by trees and must be analysed by the wave model.

History

Advocacy of the wave theory is attributed to Johannes Schmidt and Hugo Schuchardt.

In 2002 to 2007, Malcolm Ross and his colleagues theorized that Oceanic languages can be best understood as developing through the wave model.[6][7]

Applications

The Wave model provided the key inspiration to several approaches in linguistics, notably:

- Dialectology, the study of dialectal variation, which often takes the form of linguistic atlases and maps, displaying isoglosses and dialect boundaries (including fuzzy boundaries, cf. Croissant, Rhenish fan);

- Dialectometry, the quantitative and computational branch of dialectology;

- Historical glottometry, a quantitative and diffusionist approach to language subgrouping and genealogy: its main unit of observation are the individual innovations as they diffused across dialect networks and linkages (internal to a given family), resulting in genetic subgroups that form intersecting patterns;

- Areal linguistics, the study of language contact (including across different families), and of the sprachbunds that result from long periods of language convergence;

- Creole linguistics, the study of linguistic creoles and mixed languages, and of their genesis.

See also

References

- 1 2 Wolfram, Walt; Schilling-Estes, Natalie (2003), "Dialectology and Linguistic Diffusion" (PDF), in Joseph, Brian D.; Janda, Richard D. (eds.), The Handbook of Historical Linguistics, Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 713–735.

- 1 2 3 François, Alexandre (2014), "Trees, Waves and Linkages: Models of Language Diversification" (PDF), in Bowern, Claire; Evans, Bethwyn (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics, London: Routledge, pp. 161–189, ISBN 978-0-41552-789-7.

- ↑ Heggarty, Paul; Maguire, Warren; McMahon, April (2010). "Splits or waves? Trees or webs? How divergence measures and network analysis can unravel language histories". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 365 (1559): 3829–3843. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0099. PMC 2981917. PMID 21041208..

- ↑ Labov, William (2007). "Transmission and diffusion". Language. 83 (2): 344–387. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.705.7860. doi:10.1353/lan.2007.0082. S2CID 6255506.

- ↑ "I use the term linkage to refer to a group of communalects [i.e. dialects or languages] which have arisen by dialect differentiation" Ross, Malcolm D. (1988). Proto Oceanic and the Austronesian languages of Western Melanesia. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. p. 8.

- ↑ Lynch, John; Malcolm Ross; Terry Crowley (2002). The Oceanic languages. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1128-4. OCLC 48929366.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ross, Malcolm and Åshild Næss (2007). "An Oceanic Origin for Äiwoo, the Language of the Reef Islands?". Oceanic Linguistics. 46 (2): 456–498. doi:10.1353/ol.2008.0003. hdl:1885/20053. S2CID 143716078.