| Western equine encephalitis virus | |

|---|---|

| |

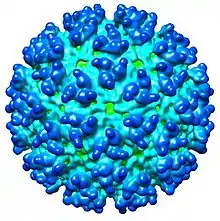

| CryoEM model of Western equine encephalitis virus, 12Å resolution. EMDB entry EMD-5210[1] | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Kitrinoviricota |

| Class: | Alsuviricetes |

| Order: | Martellivirales |

| Family: | Togaviridae |

| Genus: | Alphavirus |

| Species: | Western equine encephalitis virus |

| Western equine encephalitis virus | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

The Western equine encephalomyelitis virus is the causative agent of relatively uncommon viral disease Western equine encephalomyelitis (WEE). An alphavirus of the family Togaviridae, the WEE virus is an arbovirus (arthropod-borne virus) transmitted by mosquitoes of the genera Culex and Culiseta.[2] WEE is a recombinant virus between two other alphaviruses, an ancestral Sindbis virus-like virus, and an ancestral Eastern equine encephalitis virus-like virus. There have been under 700 confirmed cases in the U.S. since 1964. This virus contains an envelope that is made up of glycoproteins and nucleic acids. The virus is transmitted to people and horses by bites from infected mosquitoes (Culex tarsalis and Aedes taeniorhynchus) and birds during wet, summer months.[3][4]

According to the CDC, geographic occurrence for this virus is worldwide, and tends to be more prevalent in places in and around swampy areas where human populations tend to be limited. In North America, WEE is seen primarily in U. S. states and Canadian provinces west of the Mississippi River.[3] The disease is also seen in countries of South America. WEE is commonly a subclinical infection; symptomatic infections are uncommon. However, the disease can cause serious sequelae in infants and children. Unlike Eastern equine encephalitis, the overall mortality of WEE is low (approximately 4%) and is associated mostly with infection in the elderly. Approximately 15–20% of horses that acquire the virus will die or be put down.[3] There is no human vaccine for WEE and there are no licensed therapeutic drugs in the U.S. for this infection. The virus affects the brain and spinal cord of the infected host.

History

WEE was discovered in 1930 when a number of horses in the San Joaquin Valley of California, USA died of a mysterious encephalitis. Karl Friedrich Meyer investigated but was not able to isolate the pathogen from necropsies of horses that had been dead for some time and needed samples from an animal in the earlier stages of disease. When the team heard of a horse that appeared to have encephalitis, its owner threatened to shoot the scientists. However Meyer was able to convince the farmer's wife that the horse was dying anyway, and to secretly signal him when the farmer was asleep in exchange for $20 (as this was during the Great Depression, this was a substantial amount of money). Meyer and his colleagues hid in the bushes until the signal, euthanized the horse and stole its head. They successfully isolated WEEV from the brain tissue.[5]

Biological weapon

Western equine encephalitis virus was one of more than a dozen agents that the United States researched as potential biological weapons before the nation suspended its biological weapons program.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ Sherman, M. B.; Weaver, S. C. (2010). "Structure of the Recombinant Alphavirus Western Equine Encephalitis Virus Revealed by Cryoelectron Microscopy". Journal of Virology. 84 (19): 9775–9782. doi:10.1128/JVI.00876-10. PMC 2937749. PMID 20631130.

- ↑ Ryan KJ; Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- 1 2 3 "Western Equine Encephalitis Fact Sheet - Minnesota Dept. of Health". www.health.state.mn.us. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ↑ Kelser, R.A. (1937). "Transmission of the Virus of Equine Encephalomy-elîtis by Aëdes taeniorhynchus". Science (Washington). 85–2198 (2198): 178. Bibcode:1937Sci....85..178K. doi:10.1126/science.85.2198.178. PMID 17732932 – via cabdirect.org.

- ↑ Sabin, Albert (1980). "Karl Friedrich Meyer: 1884–1974" (PDF). Biogr Mem Natl Acad Sci. Washington, D.C. 52: 269–332. PMID 11620787.

- ↑ "Chemical and Biological Weapons: Possession and Programs Past and Present", James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury College, April 9, 2002, accessed 31 March 2010.