.jpg.webp)

Snow camouflage is the use of a coloration or pattern for effective camouflage in winter, often combined with a different summer camouflage. Summer patterns are typically disruptively patterned combinations of shades of browns and greys, up to black, while winter patterns are dominated by white to match snowy landscapes.

Among animals, variable snow camouflage is a type of seasonal polyphenism with a distinct winter plumage or pelage. It is found in birds such as the rock ptarmigan, lagomorphs such as the Arctic hare, mustelids such as the stoat, and one canid, the Arctic fox. Since these have evolved separately, the similar appearance is due to convergent evolution. This was used as early evidence for natural selection. Some high Arctic species like the snowy owl and polar bear however remain white all year round.

In military usage, soldiers often either exchange their disruptively-patterned summer uniforms for thicker snow camouflage uniforms printed with mainly-white versions of camouflage patterns in winter, or they wear white overalls over their uniforms. Some armies have made use of reversible uniforms, printed in different seasonal patterns on their two sides. Vehicles and guns are often simply repainted in white. Occasionally, aircraft too are repainted in snow camouflage patterns.

Among animals

White as camouflage

Charles Darwin mentioned the white winter coloration of the ptarmigan in his 1859 Origin of Species:[1]

When we see ... the alpine ptarmigan white in winter, the red-grouse the colour of heather, and the black-grouse that of peaty earth, we must believe that these tints are of service to these birds ... in preserving them from danger.[1]

The white protective coloration of arctic animals was noted by an early student of camouflage, the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, in his 1889 book Darwinism; he listed the polar bear, the American polar hare, the snowy owl and the gyr falcon as remaining white all year, while the arctic fox, arctic hare, ermine and ptarmigan change their colour, and observed "the obvious explanation", that it was for concealment, at a time when Darwinism was at a low ebb.[2] Later zoologists such as Hugh B. Cott have echoed his observations, adding that other animals of the Arctic such as musk ox, moose, reindeer, wolverine and raven never become white "even in the coldest parts of their range". Cott noted that both animals that hunt, like polar bear and stoat, and prey animals like ptarmigan and mountain hare, require camouflage to hide from prey or from predators respectively.[3] There is little experimental evidence for the adaptiveness of white as camouflage, though the ornithologist W. L. N. Tickell, reviewing proposed explanations of white plumage in birds, writes that in the ptarmigan "it is difficult to escape the conclusion that cryptic brown summer plumage becomes a liability in snow, and white plumage is therefore another cryptic adaptation." All the same, he notes, "in spite of winter plumage, many Ptarmigan in NE Iceland are killed by Gyrfalcons throughout the winter."[4]

Seasonal polyphenism

Some animals of the far north, like the snowshoe and Arctic hares, Arctic fox, stoat, and rock ptarmigan change their coat colour (by moulting and growing new fur or feathers) from brown or grey summer camouflage to white in the winter; the Arctic fox is the only species in the dog family to do so.[5] However, Arctic hares which live in the far north of Canada, where summer is very short, remain white year-round.[5][6] Since these animals in widely separated groups have evolved separately, the similarity of coloration is due to convergent evolution, on the presumption that natural selection favours a particular coloration in a particular environment.[7]

The seasonal polyphenism in willow grouse differs between Scottish and Scandinavian populations. In Scotland, grouse have two plumages (breeding and non-breeding), while in Scandinavia there is a third plumage, a white winter morph. The genetic basis for this is not in the melanin pigment system, and is probably due to regulatory changes.[8] The behaviour of moulting females in springtime depends on their plumage state: they tend to sit on snow while they are mainly white, but choose the border between bare ground and snow when they have more dark feathers. They seem to be choosing the best compromise between camouflage and food quality.[9]

The effects of climate change can lead to a mismatch between the seasonal coat coloration of arctic animals such as snowshoe hares with the increasingly snow-free landscape.[10]

| Species | In summer | In winter |

|---|---|---|

| Snowshoe hare |  |  |

| Arctic fox |  | .jpg.webp) |

| Stoat |  |  |

| Rock ptarmigan |  |  |

Military usage

The principle of varying coloration with the changing seasons has military applications.

First World War

In the First World War, firing and observation positions were hand-painted in disruptive patterns by artists known as camoufleurs, and they sometimes varied their patterns seasonally. Uniforms were largely of a single colour, such as the British khaki;[11] but snow camouflage clothes came into use in some armies by 1917.[12][13] For example, Austro-Hungarian troops on the Italian front used skis and wore snow camouflage smocks and overtrousers over their uniforms, and improvised white cloths over their uniform caps.[14]

Second World War

Several armies in the Second World War in Northern European countries preferred separate winter uniforms rather than oversuits. The Waffen-SS went a step further, developing reversible uniforms with separate schemes for summer and autumn, as well as white winter oversuits. Other German units fighting in Eastern Europe were at first poorly equipped for winter, having to make do with ordinary summer uniforms, but in the winter of 1942 to 1943 new white two-piece hooded oversuits with long mitten gauntlets started to arrive. American troops in Europe in the winter of 1944 to 1945 improvised snow capes and helmet covers from white cloth such as bed linen.[15][16][17]

The Red Army issued a report, "Tactical and Technical trends, No. 17" in January 1943 on the camouflage of tanks in winter. It advised either all-white using zinc white or titanium white paint for level, open country, or disruptive two-colour winter camouflage for areas with more variety including "forests, underbrush, small settlements, thawed patches of earth". The two colours could be achieved either by leaving around a quarter to a third of the vehicle's summer camouflage uncovered, or by repainting the whole vehicle in white with dark gray or gray-brown spots. Units were advised not to paint all their vehicles identically, but to have some tanks all white, some in white with green stripes, and some in white and gray or gray-brown. Winter camouflage was not limited to paint: tracks left in the snow were to be obliterated, vehicles parked in cover, headlights covered with white fabric, shelters constructed, or else vehicles covered with white fabric, or dark fabric scattered with snow.[18]

| Example | In summer | In winter |

|---|---|---|

| 2-pounder British anti-tank gun Summer crew in British Battledress winter crew in improvised camouflage |  |  |

| Red Army soldiers Hooded winter overalls |  |  |

| Finnish artillery Improvised winter camouflage |  |  |

| Wehrmacht/Waffen-SS soldiers and armour Two-part winter uniforms | %252C_Munition_Recolored.jpg.webp) |  |

Post-war

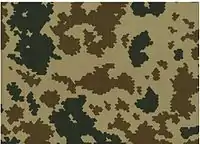

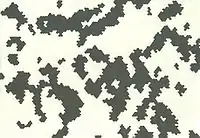

Later in the 20th century, as disruptively patterned uniforms became widespread, winter variants of patterns such as Flecktarn were developed, the background colour (such as green) being replaced with white to form a Schneetarn (snow camouflage pattern).[19] Aircraft deployed in winter have sometimes been snow camouflaged, as with Sepecat Jaguars on exercise in Norway.[20]

| Example | In summer | In winter |

|---|---|---|

| Flecktarn/Schneetarn disruptive camouflage patterns |  |  |

| Finnish Defence Forces digital desert/snow patterns |  |  |

| Royal Air Force Jaguar summer/winter paint schemes |  |  |

| Ghillie suit summer/winter |

.jpg.webp) |  |

References

- 1 2 Darwin, Charles (1859). Origin of Species. Murray. p. 84.

- ↑ Alfred Russel Wallace (2015) [1889]. Darwinism - An Exposition Of The Theory Of Natural Selection - With Some Of Its Applications. Read Books. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-4733-7510-9.

- ↑ Cott, Hugh B. (1940). Adaptive Coloration in Animals. Methuen. pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Tickell, W. L. N. (March 2003). "White Plumage". Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology. 26 (1): 1–12. JSTOR 1522461.

- 1 2 "Arctic Wildlife". Churchill Polar Bears. 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ↑ Hearn, Brian (20 February 2012). The Status of Arctic Hare (Lepus arcticus bangsii) in Insular Newfoundland (PDF). Newfoundland Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation. p. 7. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Rohwer, Sievert (1975). "The Social Significance of Avian Winter Plumage Variability". Evolution. 29 (4): 593–610. doi:10.2307/2407071. JSTOR 2407071. PMID 28563094.

- ↑ Skoglund, Pontus; Höglund, Jacob (2010). "Sequence Polymorphism in Candidate Genes for Differences in Winter Plumage between Scottish and Scandinavian Willow Grouse (Lagopus lagopus)". PLOS ONE. 5 (4): e10334. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...510334S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010334. PMC 2859059. PMID 20428241.

- ↑ Steen, Johan B.; Erikstad, Kjell Einar; Høidal, Karsten (1992). "Cryptic Behaviour in Moulting Hen Willow Ptarmigan Lagopus l. lagopus during Snow Melt". Ornis Scandinavica. 23 (1): 101–104. doi:10.2307/3676433. JSTOR 3676433.

- ↑ Mills, L. Scott; Marketa Zimova; Jared Oyler; Steven Running; John T. Abatzoglou; Paul M. Lukacs (2013). "Camouflage mismatch in seasonal coat color due to decreased snow duration". PNAS. 110 (18): 7360–7365. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.7360M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1222724110. PMC 3645584. PMID 23589881.

- ↑ Newark, Tim (2007). Camouflage. Thames & Hudson. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-0-500-51347-7.

- ↑ Bull, Stephen (2004). Encyclopedia of Military Technology and Innovation. Greenwood. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-57356-557-8.

- ↑ Englund, Peter (2011). The Beauty And The Sorrow: An intimate history of the First World War. Profile Books. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-84765-430-4.

- ↑ "The Austro-Hungarian Army on the Italian Front, 1915–1918". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ↑ Brayley, Martin J. (2009). Camouflage uniforms : international combat dress 1940–2010. Ramsbury: Crowood. pp. 37 and passim. ISBN 978-1-84797-137-1.

- ↑ Peterson, D. (2001). Waffen-SS Camouflage Uniforms and Post-war Derivatives. Crowood. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-86126-474-9.

- ↑ Rottman, Gordon L. (2013). World War II Tactical Camouflage Techniques. Bloomsbury. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-1-78096-275-7.

- ↑ Carruthers, Bob (2013) [28 January 1943]. Wehrmacht Combat Reports: The Russian Front. Pen and Sword. pp. 62–64. ISBN 978-1-4738-4534-3.

- ↑ Zäch, Sebastian. "Schneetarn". Bundeswehr (German Army). Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ "Jaguar snow camo". Sepecat. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

.jpg.webp)