| Worksop | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

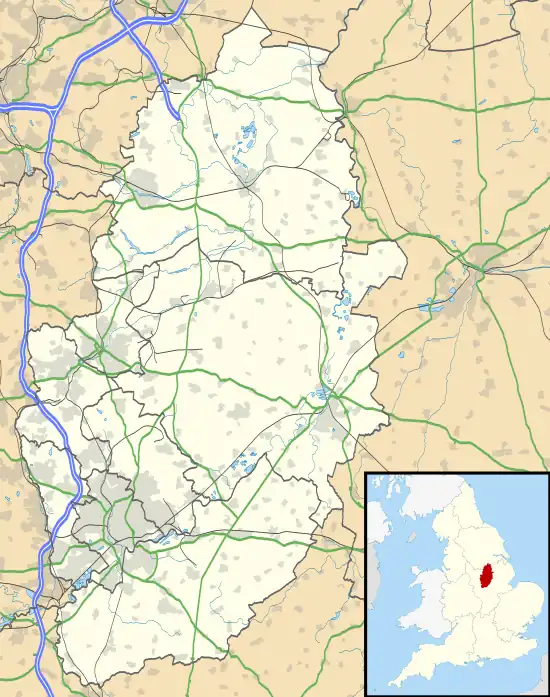

Worksop Location within Nottinghamshire | |

| Population | 44,733 [1] |

| Demonym | Worksopian |

| OS grid reference | SK 58338 78967 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | WORKSOP |

| Postcode district | S80, S81 |

| Dialling code | 01909 |

| Police | Nottinghamshire |

| Fire | Nottinghamshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

Worksop (/ˈwɜːrksɒp/ WURK-sop) is a market town in the Bassetlaw District in Nottinghamshire, England. It is located 15 miles (24 km) south of Doncaster, 15 miles (24 km) south-east of Sheffield and 24 miles (39 km) north of Nottingham. Located close to Nottinghamshire's borders with South Yorkshire and Derbyshire, it is on the River Ryton and not far from the northern edge of Sherwood Forest. Other nearby towns include Chesterfield, Gainsborough, Mansfield and Retford. The population of the town was recorded at 44,733 in the 2021 Census.[2]

History

Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman history

Worksop was part of what was called Bernetseatte (burnt lands) in Anglo-Saxon times.[3] The name Worksop is likely of Anglo-Saxon origin, deriving from a personal name "We(o)rc" plus the Anglo-Saxon placename element "hop" (valley). The first element is interesting because while the masculine name Weorc is unrecorded, the feminine name Werca (Verca) is found in Bede's Life of St Cuthbert. A number of other recorded place names contain this same personal name element.[4][5]

In the Domesday Book of 1086, Worksop appears as "Werchesope". Thoroton[6] states that the Doomesday Book records that before the Norman conquest, Werchesope (Worksop) had belonged to Elsi, son of Caschin, who had "two manors in Werchesope, which paid to the geld as three car". After the conquest, Worksop became part of the extensive lands granted to Roger de Busli. At this time, the land "had one car. in demesne, and twenty-two sochm. on twelve bovats of this land, and twenty-four villains, and eight bord. having twenty-two car. and eight acres of meadow, pasture wood two leu. long, three quar. broad." This was valued at 3l in Edward the Confessor's time and 7l in the Domesday Book. De Busli administered this estate from his headquarters in Tickhill.

The manor then passed to William de Lovetot, who established a castle and endowed the Augustinian priory around 1103. After William's death, the manor was passed to his eldest son, Richard de Lovetot, who was visited by King Stephen, at Worksop, in 1161.[7] In 1258, a surviving inspeximus charter confirms Matilda de Lovetot's grant of the manor of Worksop to William de Furnival (her son).

Medieval and early modern history

A skirmish occurred in the area during the Wars of the Roses on 16 December 1460, commonly known as the Battle of Worksop.

In 1530, Worksop was visited by Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, who was on his way to Cawood, in Yorkshire. "Then my lord [Wolsey] intending the next day to remove from thence [Newstead Abbey] there resorted to him the Earl of Shrewsbury's keeper, and gentlemen, sent from him, to desire my lord, in their maister's behalf, to hunt in a parke of their maister's, called Worsoppe Parke." (Cavendish's Life of Wolsey)

A surviving (Cotton) manuscript written by Henry VIII nominated Worksop as one of three places in Nottinghamshire (along with Welbeck and Thurgarton) to become "Byshopprykys to be new made", but nothing was to come of this (White 1875), and the priory later became a victim of the Dissolution of the Monasteries - being closed in 1539, with its prior and 15 monks pensioned off. All the priory buildings, except the nave and west towers of the church, were demolished at this time and the stone reused elsewhere.

In 1540, John Leland noted that Worksop castle had all but disappeared, saying it was: "clene down and scant knowen wher it was". Leland noted that at that time Worksop was "a praty market of 2 streates and metely well buildid."

Worksop Manor became a prison for Mary, Queen of Scots in 1568. In 1580s the new house was built on the same site for George Talbot, 6th Earl of Shrewsbury. He was the husband of Elizabeth Talbot, Bess of Hardwick.

_-_geograph_5542991.jpg.webp)

In the hearth tax records of 1674, Worksop is said to have had 176 households, which made it the fourth-largest settlement in Nottinghamshire after Nottingham (967 households), Newark (339), and Mansfield (318). At this time, the population is estimated to have been around 748 people.

Modern history

By 1743, 358 families were in Worksop, with a population around 1,500. This had risen by 1801 to 3,391, and by the end of the 19th century had reached 16,455.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Worksop benefitted from the building of the Chesterfield Canal, which passed through the town in 1777, and the subsequent construction of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway in 1849. This led to growth that was further boosted by the discovery of coal seams beneath the town.

Worksop and area surrounding are known as the "Gateway to the Dukeries" due to the former ducal seats of Clumber House, Thoresby Hall, Welbeck Abbey, and Worksop Manor either owned by the Dukes of Newcastle, Portland and Kingston.[8]

Transport

Waterways

Worksop is connected to the UK Inland Waterways network by the Chesterfield Canal. It was built to export coal, limestone and lead from Derbyshire; iron from Chesterfield; and corn, deals, timber, groceries and general merchandise into Derbyshire. Today, the canal is used for leisure purposes together with the adjacent Sandhill Lake.[9]

Railway

Worksop lies on the Sheffield-Lincoln line and the Robin Hood line. Northern services run between Sheffield, Lincoln and Leeds;[10] East Midlands Railway services from Nottingham, via Mansfield, terminate at the station.[11]

Roads

Worksop lies on the A57 and A60, with links to the A1 and M1. The A57 Worksop bypass was opened on Thursday 1 May 1986, by Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State Michael Spicer and the Chairman of Bassetlaw council. The bypass had been due to open in October 1986 and was built by A.F. Budge of Retford;[12] as part of the contract, a small part of the A60, Turner Road, was opened on Monday 29 September 1986, three months early.[13]

Cycling

National Cycle Route 6, a waymarked route between London and the Lake District, passes through the town.[9]

Buses

Stagecoach East Midlands operates bus services in and around the town, with destinations including Doncaster, Rotherham, Chesterfield and Nottingham.[14]

Education

Primary

|

|

|

Secondary

Further education

- North Nottinghamshire College

- Outwood Post-16 centre

Healthcare

Worksop is served by Bassetlaw District General Hospital, part of the Doncaster and Bassetlaw NHS Foundation Trust. Bassetlaw Hospital treats about 33,000 people each year, ad roughly 38,000 emergencies. Bassetlaw Hospital is one of the University of Sheffield teaching hospitals and medical school.

Mental health services in Worksop are provided by Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust, which provide both in-patient and community services. Wards run by Nottinghamshire Healthcare provide training for medical students at the University of Nottingham.

Local economy

Current economy

The local economy in Worksop is dominated by service industries, manufacturing, and distribution. Unemployment levels in the area are now lower than the national average, owing to large number of distribution and local manufacturing companies, including Premier Foods, RDS Transport, Pandrol UK Ltd, and Laing O'Rourke.

Major employers in the area include Premier Foods (Worksop Factory), Greencore, RDS Transport (the Flying Fridge), B&Q, MAKE polymers,[15] OCG Cacao, part of Cargill, Pandrol, GCHQ, and the National Health Service (Doncaster and Bassetlaw NHS Trust).

Agricultural and forestry

John Harrison's survey of Worksop for the Earl of Arundel reveals that at that time, most people earned their living from the land. A tenant farmer, Henry Cole, farmed 200 acres of land, grazing his sheep on "Manton sheepwalk". This survey also described a corn-grinding water mill (Bracebridge mill) and Manor Mill situated near to Castle Hill, with a kiln and a malthouse.

One unusual crop associated with Worksop is liquorice. This was originally grown in the priory gardens for medicinal purposes but continued until around 1750. William Camden records in Britannia that the town was famous for growing liquorice. John Speed noted: "In the west, near Worksop, groweth plenty of Liquorice, very delicious and good". White says the liquorice gardens were "principally situated on the eastern margin of the park, near the present 'Slack Walk'." He notes that the last plant was dug up about "fifty years ago" and that this last garden had been planted by "the person after whom the 'Brompton stock' is named". A pub in Worksop is now named after this former industry.[16]

Additionally, with much of the area being heavily forested, timber was always an important industry, supplying railway sleepers to the North Midland Railway, timber for the construction of railway carriages, and packing cases for the Sheffield cutlery industry. The town also became notable for the manufacture of Worksop Windsor chairs. Timber firms in the town included Benjamin Garside's woodyard and Godley and Goulding, situated between Eastgate and the railway.[17]

Brewing and malting

The malting trade began in Retford, but gradually moved to Worksop, where it became an important trade, though it never employed many people. In 1852, Clinton malt kilns were built. Worksop has a strong tradition of brewing, including being the site of the historic Worksop and Retford Brewery. This brewery had previously been known as Garside and Alderson and Prior Well Brewery.

The brewing tradition is continued by a number of local independent breweries in and around the town, including Welbeck Abbey Brewery.[18]

Former Mining

At the start of the 19th century, Worksop had a largely agricultural economy with malting, corn milling, and timber working being principal industries. However, the discovery of coal meant that by 1900, the majority of the workforce was employed in coal mining, which provided thousands of jobs - both directly and indirectly - in and around Worksop for most of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The first coal mine was Shireoaks Colliery, which by 1861 employed over 200 men, which rose to 600 men by 1871. Steetley Colliery started producing coal in 1876, and in Worksop a mine was developed on land to the south-east, owned by Henry Pelham-Clinton, 7th Duke of Newcastle. This mine was fully operational in around 1907, with three shafts, and was named Manton Colliery.

The closure in the 1990s of the pits, compounding the earlier decline of the timber trade and other local industry, resulted in high unemployment in parts of the Worksop area, as well as other social problems.[19]

Textiles

In John Harrison's survey of Worksop for the Earl of Arundel, a dye house and a tenter green (where lengths of cloth were stretched out to dry) indicates a small cloth industry was present in Worksop. Late attempts during the Industrial Revolution to introduce textile manufacturing saw two mills constructed, one at Bridge Place and the other somewhere near Mansfield Road. Both enterprises failed and closed within three years. They were converted to milling corn.

Religion

Worksop has three churches, all of which are on the National Heritage List for England.

Officially titled the Priory Church of Saint Mary and Saint Cuthbert, the Anglican parish church is usually known as Worksop Priory. It was an Augustinian priory founded in 1103. The church has a nave and detached gatehouse. Monks at the priory made the Tickhill Psalter, an illuminated manuscript of the medieval period, now held in New York Public Library. After the dissolution of the monasteries, the east end of the church fell into disrepair, but the townspeople were granted the nave as a parish church. The eastern parts of the building have been restored in several phases, the most recent being in the 1970s when architect Lawrence King rebuilt the crossing.

St. Anne's Church is an Anglican parish church and is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade-II listed building.[20] The church was built in 1911 by the Lancaster architects Austin and Paley.[21][22] The church has an historic pipe organ originally built by Gray and Davison in 1852 for Clapham Congregational Church.

.jpg.webp)

St. John's Church is a parish church built between 1867 and 1868 by architect Robert Clarke.

St Mary's is a Roman Catholic church, built from 1838 to 1840 and paid for by the Bernard Howard, 12th Duke of Norfolk, after the sale of Worksop Manor, which the duke owned. The church was designed by Matthew Ellison Hadfield and it is a Grade II-listed building. In late 1913, the church was visited by Archduke Franz Ferdinand seven months before his assassination in Sarajevo.[23]

Relatively few religious minorities live in the town, with the largest non-Christian community being Worksop's 243 Muslims.[24] A small community and prayer centre for adherents is on Watson Road.[25]

Local Media

The town receives local news and television programmes from the BBC and ITV Yorkshire region rather than the East Midlands. Local radio stations are BBC Radio Sheffield on 104.1 FM, Greatest Hits Radio South Yorkshire on 107.9 FM, and Trust AM, an online hospital radio station serving the Bassetlaw District General Hospital in the town. The local newspapers are the Nottingham Evening Post, Worksop Guardian and Worksop Trader.

Places of interest

Mr Straw's House, the family home of the Straw family, was inherited by the Straw brothers, William and Walter, when their parents died in the 1930s. The house remained unaltered until the National Trust acquired it in the 1990s and opened it to the public.[26]

Clumber Park, located south of Worksop, is a country park, also owned by the National Trust. It has 3,800 acres of parkland.[27]

Worksop Town Hall was originally established as a corn exchange, designed by Isaac Charles Gilbert, which opened in 1851.[28]

The Worksop War Memorial is a large Grade II* listed cenotaph dedicated to the memory of local residents that died during World War I and II.[29]

Notable people

- A'Whora (real name George Boyle, b. 1996), drag queen, fashion designer and TV personality, known from RuPaul's Drag Race UK.[30]

- James Walsham Baldock (1822–1898), artist, adopted by his grandfather who was a farmer at Worksop[31]

- Maurice Bembridge (b.1945), golfer[32]

- George Best, former goalkeeper with Blackpool F.C.

- Basil Boothroyd (1910-1988), humorous writer[33]

- Bruce Dickinson (b.1958), singer with Iron Maiden[34]

- Craig Disley (b.1981), footballer

- Mark Foster (b.1975), golfer

- Anne Foy (b.1986), former BBC Children's TV presenter[35]

- Alexina Graham (b.1990), model and Victoria's Secret Angel

- Gwen Grant (b.1940), writer[36]

- Henry Haslam (1879-1942), footballer and Olympic gold medalist at the 1900 Olympics[37]

- Sarah-Jane Honeywell (b.1974), BBC Children's TV presenter[38]

- William Henry Johnson (1890-1945), recipient of a Victoria Cross[39]

- Mick Jones (b.1945), Sheffield United and Leeds United striker during the 1960s and 1970s

- Sam Osborne (b.1993), racing driver

- John Parr (b.1954), musician[40]

- Henry Pickard (1832-1905), cricketer[41]

- Donald Pleasence (1919-1995), actor[42]

- Graham Taylor (1944-2017), former England, Aston Villa and Watford manager[43]

- Danny Thomas (b.1961), footballer, played for Coventry City F.C. and Tottenham Hotspur

- Sam Walker (b.1995), table tennis player[44]

- Darren Ward (b.1974), former football goalkeeper

- Lee Westwood (b.1973), golfer[45]

- Elliott Whitehouse (b.1993), footballer

- Chris Wood (b.1987), footballer

See also

References

- ↑ "WORKSOP in Nottinghamshire (East Midlands)".

- ↑ "Worksop, United Kingdom — statistics 2023". zhujiworld.com. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ "Anglo Saxon Nottinghamshire" (PDF). Archaeology Data Service.

- ↑ The Place-Names of Nottinghamshire Their Origin and Development, Heinrich Mutschmann, Cambridge, 1913

- ↑ Andrew Nicolson. "Worksop". Nottinghamshire Heritage Gateway.

- ↑ Thoroton's History of Nottinghamshire: Volume 3, Republished with Large Additions by John Throsby, Nottingham, 1796

- ↑ Worksop the Dukery and Sherwood Forest, Robert White, 1875

- ↑ Bassetlaw District Council, History of Worksop, 2019 retrieved on the 1st April 2023

- 1 2 "Worksop Central Green Infrastructure Strategy" (PDF). Bassetlaw District Council. December 2021. pp. 27, 36. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ↑ "Timetables and engineering information for travel with Northern". Northern Railway. May 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ↑ "Timetables". East Midlands Railway. May 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ↑ Retford Times Thursday 1 May 1986, page 18

- ↑ Retford Times Thursday 2 October 1986, page 1

- ↑ "Stops in Worksop". Bus Times. 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ↑ "Site confirmed for MBA Polymers' UK plant". Recycling International. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ↑ "The Liquorice Gardens, Worksop".

- ↑ Stroud, G. (2002) Nottinghamshire Extensive Urban Survey, Worksop. English Heritage

- ↑ Nanrah, Gurjeet (1 January 2020). "Inside the historic Nottinghamshire estate..." Nottinghamshire Post. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ Boniface, Susie (24 October 2010). "George Osborne wreaks havoc .. just like Margaret Thatcher in 1980s". The Mirror.

- ↑ Historic England, "Church of St Anne, Worksop (1045754)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 30 August 2012

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ Pevsner 1979, p. 389.

- ↑ Brandwood et al. 2012, p. 248.

- ↑ Historic England, Worksop - St Mary, Taking Stock, retrieved 5 May 2022

- ↑ "Worksop".

- ↑ "Muslim prayer centre to open in Worksop".

- ↑ Mr Straw's House Archived 8 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine by The National Trust, accessed 28 May 2006.

- ↑ "Clumber Park". National Trust. 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ↑ Historic England. "Worksop Town Hall (1045762)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ↑ "Worksop - Cenotaph (Memorial Avenue)". secure.nottinghamshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ↑ "Worksop fashion designer set to dazzle in BBC's RuPaul's Drag Race UK". www.worksopguardian.co.uk. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ↑ "James Walsham Baldock". www.avictorian.com. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ↑ Townsend, Mark (22 March 2018). "Recalling one of the most fascinating two hours in Masters history". National Club Golfer.

- ↑ "Basil Boothroyd". imdb.

- ↑ "Worksop-born Bruce bringing Iron Maiden close to home". Worksop Guardian. 3 May 2017.

- ↑ "Official site". Concorde International Artistes. Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ↑ "Nottinghamshire County Council Literature Newsletter" (PDF). Nottinghamshire County Council. p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ↑ "Biographical information". olympedia.org. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ↑ "Clean for 16 years". Doncaster Free Press. 5 January 2018.

- ↑ "William Henry Johnson VC". VC Online. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ↑ "John Parr Concert Photos". Concert Archives.

- ↑ "Henry Pickard". Espn Cricinfo. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ↑ "Donald Pleasence's Biography". www.pleasence.com.

- ↑ "Worksop-born former England manager Graham Taylor dies". Worksop Guardian. 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "Profile".

- ↑ "Profile". www.leewestwood.golf.

Further reading

- Brandwood, Geoff; Austin, Tim; Hughes, John; Price, James (2012), The Architecture of Sharpe, Paley and Austin, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-84802-049-8

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1979), Nottinghamshire, Pevsner Architectural Guides: Buildings of England (2nd ed.), New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0300096361