| Wren's Nest | |

|---|---|

Fossilized ripple markings at Wren's Nest | |

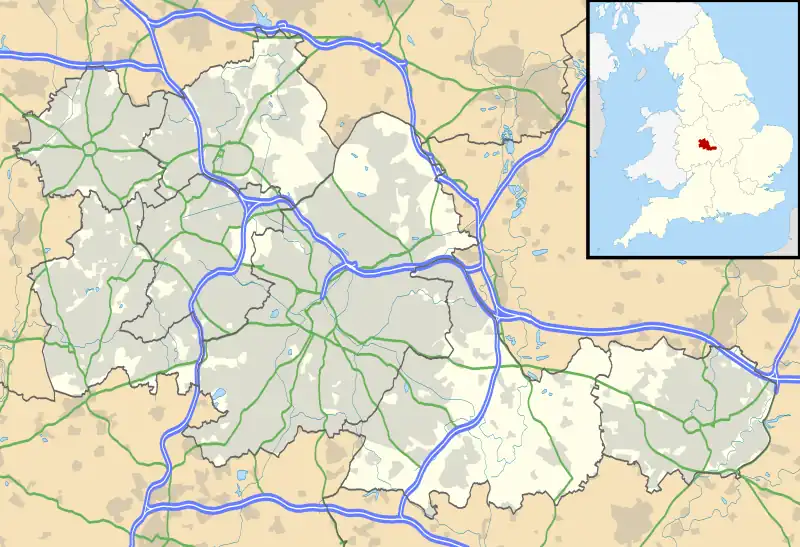

Location of Wren's Nest within the West Midlands | |

| Type | Nature reserve |

| Location | Dudley, West Midlands, England |

| OS grid | SO937921 |

| Coordinates | 52°31′34″N 2°05′37″W / 52.526°N 2.0936°W |

| Created | 1956 |

| Operated by | Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council |

| Open | All year |

| Website | link |

The Wren's Nest is a geological Site of Special Scientific Interest in the Dudley Metropolitan Borough, north west of the town centre of Dudley, in the West Midlands of England. It is one of the most important geological locations in Britain.[1][2] It is also a Local Nature Reserve,[3][4] a national nature reserve (NNR) and Scheduled Ancient Monument.[5][6] The site is home to a number of species of birds and locally rare flora, such as Scabiosa columbaria (small scabious), milkwort and quaking grass.[7] The caverns are also a nationally important hibernation site for seven different species of bat.[5][8]

The Wren's Nest National Nature Reserve

Ancient history

The Wren's Nest National Nature Reserve is world-famous geologically for its well-preserved Silurian coral reef fossils. Considered the most diverse and abundant fossil site in the British Isles,[9] more than 700 types of fossil have been found at the site, 86 of which are unique to the location,[10] including Calymene blumenbachii, a trilobite nicknamed the Dudley Bug or Dudley Locust by 18th century quarrymen.[11] An image of this trilobite featured on the town's coat of arms until 1974.[6]

The limestone outcrops belong to the Wenlock Group, which was formed some 420 to 425 million years ago from the material remnants of an ancient tropical sea bed,[6][11] and contain ripple marks made from the sea's action on the sand. Wren's Nest Hill was extensively quarried during the Industrial Revolution for building stone and lime production.[5][6] The site was originally studied by the Scottish paleontologist Sir Roderick Murchison, whose work in defining the Silurian System was mainly based on fossils and rock formations found at the site.[5]

Silurian sea bed fossils collected from Wren's Nest Nature Reserve, Dudley UK. June 2014. |

Silurian sea bed fossils collected from Wren's Nest Nature Reserve, Dudley UK. June 2014. |

Closer view of Silurian sea bed fossils collected from Wren's Nest Nature Reserve, Dudley, UK |

Silurian sea bed fossils collected from Wren's Nest Nature Reserve, Dudley UK. June 2014. |

Silurian sea bed fossils collected from Wren's Nest Nature Reserve, Dudley UK. June 2014. |

Silurian sea bed fossils collected from Wren's Nest Nature Reserve, Dudley UK. June 2014. |

Industrial Revolution

Abraham Darby I, who was one of the fathers of the Industrial Revolution, was born on Wren's Nest Hill in 1678.[6]

The caves were mined for hundreds of years for the valuable limestone, used firstly for mortar and agriculture, and then principally iron production during the Industrial Revolution. The Victorians installed the world's first industrial steam engine next to the Wren's Nest, which pumped water from mines and access tunnels.[12]

During the height of the Industrial Revolution, up to 20,000 tons of limestone was quarried annually.[6] Local industrialisation was considerable at this time, as the district had become highly industrialised in the heyday of the Black Country's industrial past. When quarrying officially finished in 1925, the site was abandoned.

Recent history

Wren's Nest was declared a national nature reserve in 1956, the UK's first national nature reserve for geology.[6][13]

In 2004, Wren's Nest and the nearby Castle Hill were declared Scheduled Ancient Monuments, as they represented the best surviving remains of the limestone industry in Dudley. The most impressive part of this is the last remaining surface opening limestone cavern in the world – formerly reaching more than 100 metres underground – which is known as the Seven Sisters. The workings were originally connected by underground canal to the Dudley Tunnel complex, which has now been blocked off for safety reasons.[8]

The Wren's Nest's geological value was first recognised by Sir Roderick Murchison in 1839, and now both the ex-quarry and the tunnels are visited by scientists from all over the world to study its valuable content.[6][12]

The Seven Sisters tunnel complex

Considered one of the best surviving examples of limestone quarrying,[14] the Seven Sisters caverns had to be filled in after a major roof collapse and mine cave-in occurred in 2001, to prevent further collapse.[8] More recent work had also began on infilling the huge Cathedral Gallery with loose sand. The former limestone mine and adjacent vast underground canal basin, which leads to a now blocked off passage to Dudley Tunnel, contain some of what local historians claimed to be some of the world's most important geology and mining heritage.[6]

In 2007, Dudley Council lost out on a £50,000,000 national lottery grant to redevelop and re-open the cavern complex,[15] but did later secure an £800,000 grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund for lesser improvements to the site.[16]

See also

External links

References

- ↑ "Wren's Nest citation" (PDF). Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ "Map of Wren's Nest". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ "Wren's Nest". Local Nature Reserves. Natural England. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ↑ "Map of Wren's Nest". Local Nature Reserves. Natural England. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Wren's Nest National Nature Reserve". Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Wren's Nest – a geological gem". BBC News. 1 December 2009.

- ↑ "Wildlife at Wren's Nest". BBC. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Wren's Nest: history set in stone". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ "Wren's Nest". Black Country Geological Society. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ "Fossils". Wren's Nest National Nature Reserve. Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- 1 2 "The secret cave world beneath Dudley that could open up with lottery funds". Birmingham Live. 29 November 2007.

- 1 2 "Welcome!". Friends of Wrens Nest National Nature Reserve. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- ↑ "Geology". Discover Dudley. Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ "Seven Sisters Cavern". Black Country History. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ "Last chance for Seven Sisters project". Express & Star. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ↑ "Works starts to improve Dudley nature reserve". Stourbridge News. Retrieved 8 April 2012.