Yamaga Sokō | |

|---|---|

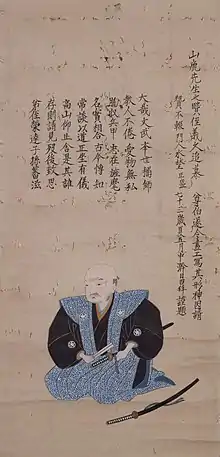

Portrait of Yamaga Sokō, with inscription by Mizuno Masamori | |

| Born | September 21, 1622 Aizuwakamatsu, Japan |

| Died | October 23, 1685 (aged 63) Edo, Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Occupation(s) | Philosopher, writer |

Yamaga Sokō (山鹿 素行, 21 September 1622 – 23 October 1685) was a Japanese military writer and philosopher under the Tokugawa shogunate of Edo period in Japan. As a scholar he applied the Confucian idea of the "superior man" to the samurai class of Japan. This became an important part of the samurai way of life and code of conduct.

Biography

Yamaga was born in Aizuwakamatsu the son of a rōnin formerly of Aizu Domain and moved to Edo at the age of six in 1628. He had been studying the Chinese classics from that time, and at the age of nine became a student of Hayashi Razan, a follower of Neo-Confucianism who had developed a practical blending of Shinto and Confucian beliefs and practices which became the foundation for the dominant ideology of the Tokugawa shogunate.[1] At the age of 15, he travelled to Kai Province to study military strategy under Obata Kagenori.

However, at the age of forty he broke away from the official doctrine, rejecting the Cheng–Zhu school promoted by the Hayashi clan and burning all of the books he had written while under its influence. This, along with the publishing of a philosophical work entitled Seikyo Yoroku, caused him to be arrested the following year at the instigation of Hoshina Masayuki, daimyō of Aizu Domain. Yamaga proclaimed his belief that the unadulterated truth could be found only in the ethical teachings of Confucius, and that subsequent developments within the Confucian tradition represented perversions of the original doctrine. Hoshina, however, saw this attack on the prevailing orthodoxy as a potential challenge to Tokugawa authority itself and ordered his exile from Edo. Soon after his expulsion from Edo, Yamaga moved to the Akō Domain in Harima Province in 1653, befriending Asano Nagatomo and becoming an important teacher of Confucianism and military science in the region. Yamaga's influence would later be expressed in the Genroku Akō incident, as its leader, Ōishi Yoshio, had been one of his devoted pupils. [2]

Yamaga wrote a series of works dealing with "the warrior's creed" (bukyō) and "the way of the gentleman" (shidō). In this way he described the lofty mission of the warrior class and its attendant obligations. According to William Scott Wilson in his Ideals of the Samurai, Yamaga "in his theory of Shidō (a less radical theory than bushidō), defined the warrior as an example of Confucian purity to the other classes of society, and as punisher of those who would stray from its path". Wilson wrote that Yamaga thought of the samurai as a "sort of Warrior-Sage" and focused his writings on the perfection of this "transcendent ideal", but "this direction of thinking ... was typical of the scholars of the Edo Period in its tendency toward speculation". He re-emphasized that the peaceful arts, letters, and history were essential to the intellectual discipline of the samurai. Yamaga thus symbolizes the historical transformation of the samurai class from a purely military aristocracy to one of increasing political and intellectual leadership.[3] One of his pupils was Daidōji Yūzan, a samurai from the Daidōji family, who would become the author of an important bushidō text, Budō shoshin shu. He also drew attention to the need to study and adopt Western weapons and tactics, as introduced by the Dutch.

The life of his near contemporary Matsudaira Sadanobu presents a plausible context for more fully understanding and appreciating Yamaga's life. Both believed entirely in the civic and personal values of Confucianism, but both construed those precepts a little differently because of their places in Edo period society.[4] In his own time, this conception of Confucian values was among the factors that led him to draw attention to the need to study and adopt Western weapons and tactics, as introduced by the Dutch.

Yamaga's conception restated and codified the writings of past centuries and pointed to the emperor as the focus of all loyalties. His teachings, therefore, had direct application for everyone in the existing feudal structure, and he was not calling for a change in the status of the emperor.

.JPG.webp)

Yamaga was pardoned in 1675 and allowed to return to Edo, where he taught military studies for the next 10 years. He died in 1685, and his grave is at the Sōtō Zen temple of Sōsan-ji in Shinjuku, Tokyo. His grave was designated a National Historic Site in 1943.[5]

Chucho Jijitsu

An important theme running through Yamaga's life and works was a focus on the greatness of Japan, and this became one of the reasons his popularity and influence were to expand in the rising nationalistic culture of the mid-twentieth century.[6]

Living at a time when very few texts were written in Japanese and Japanese scholars devoted themselves to the study of Chinese history, Chinese literature, and Chinese philosophy, he wrote the Chucho Jijitsu (which translates as "Actual Facts about the Central Realm") to awaken Japanese scholars to the greatness of their own national history and culture. His argument is that Japan is a gift of the gods to the Japanese people, and that while many nations (here his readers would have understood him to refer to China) consider their country to be the center of the world, on the objective basis of temperate climate, only China and Japan can justify such claims, and of the two Japan is clearly superior because it is favored by the gods, as proven by the fact that only in Japan is there an unbroken Imperial line descended from the gods themselves.[7]

The tone of the work can be appreciated in this excerpt:

"The water and soil of Japan excel those of all other countries, and the qualities of its people are supreme throughout the eight corners of the earth. For this reason, the boundless eternity of its gods and the endlessness of the reign of its sacred line, its splendid works of literature and glorious feats of arms, shall be as enduring as heaven and earth."[8]

Notes

- ↑ Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric et al. (2005). "Yamaga Sokō" in Japan encyclopedia, p. 1038., p. 1038, at Google Books; n.b., Louis-Frédéric is pseudonym of Louis-Frédéric Nussbaum, see Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Authority File Archived 2012-05-24 at archive.today.

- ↑ Trumbull, Stephen. (1996). The Samurai: A Military History. p. 265; Tucker, John. (2002). "Tokugawa Intellectual History and Prewar Ideology: The Case of Inoue Tetsujirō, Yamaga Sokō, and the Forty-Seven Rōnin", in Sino-Japanese Studies. Vo. 14, pp. 35–70.

- ↑ De Bary, William et al. (2001). Sources Of Japanese Tradition: Volume 2, 1600 to 2000, p. 186.

- ↑ Shuzo Uenaka. (1977). "Last Testament in Exile. Yamaga Sokō's Haisho Zampitsu", Monumenta Nipponica, 32:2, No. 2, pp. 125–152.

- ↑ "山鹿素行墓" [grave of Takashima Shuhan] (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ↑ Varley, Paul. (20000). Japanese Culture. p. 213.

- ↑ Earl, David Magarey, Emperor and Nation in Japan,; Political Thinkers of the Tokugawa Period, University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1964, pp. 45 ff.

- ↑ cited in Earl, David Magarey, Emperor and Nation in Japan,; Political Thinkers of the Tokugawa Period, University of Washington Press, Seattle, 1964, p. 46

References

- De Bary, William Theodore, Carol Gluck and Arthur E. Tiedemann . (2001). Sources Of Japanese Tradition: 1600 to 2000. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12984-X

- Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 48943301

- Shuzo Uenaka. (1977). "Last Testament in Exile. Yamaga Sokō's Haisho Zampitsu", Monumenta Nipponica, 32:2, No. 2, pp. 125–152.

- Trumbull, Stephen. (1977). The Samurai: A Military History. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-620540-5 (cloth) [reprinted by RoutledgeCurzon, London, 1996. ISBN 978-1-873410-38-7 (paper)]

- Tucker, John. (2002). "Tokugawa Intellectual History and Prewar Ideology: The Case of Inoue Tetsujirō, Yamaga Sokō, and the Forty-Seven Rōnin," in Sino-Japanese Studies. Vo. 14, pp. 35–70.

- Varley, H. Paul. (2000). Japanese Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2152-1

External links

- Columbia University:Notes on the writings of Yamaga Sokō

- East Asian Institute, University of Cambridge: Further reading/bibliography