Ziba Burrill Oakes (1807 – May 25, 1871) was a broker of slaves and real estate in Charleston, South Carolina. Oakes is significant in the history of American slavery in part due to his construction of what he called a "shed" at 6 Chalmers Street.[1] The shed still stands and is now Charleston's Old Slave Mart Museum.[2] The site as a whole, once a much larger assemblage of buildings and pens, was generally known as Ryan's mart or Ryan's nigger-jail,[3] and shut down in late 1864 or early 1865, supposedly "when owners Thomas Ryan and Z.B. Oakes went off to fight in the war."[2] Come the end of the American Civil War, writer and abolitionist James Redpath took it upon himself to visit Charleston's negro mart and liberate the slavery-related business documents that remained therein.[4] The 652 letters to Z.B. Oakes looted by Redpath were eventually turned over to abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and in 1891 became a part of the anti-slavery special collections at the Boston Public Library.[5][4] The letters remain a significant primary source in the study of the 19th-century American slave trade.[4]

Life and work

Early years

Oakes was a Yankee by extraction, born in Sangerville, Maine to a colonial-era family with roots in Massachusetts and the District of Maine.[6] Per a genealogy by historian Henry Lebbeus Oak (workshop of Hubert Howe Bancroft), Ziba Oakes was one of three children born to a prosperous merchant named Samuel Oakes (1784–1845) and his wife Mary Burrill (1787–1880), daughter of Ziba Burrill.[6] In about 1817 Samuel Oakes moved from the family from Maine to South Carolina for reasons unknown; the northern branches of the family were left with no notion of "what induced him to settle in the South."[6]

According to a newspaper article published at the time of his death, Ziba Oakes arrived in Charleston when he was 10 years old and was "educated at the school of the late Bishop England. His first connection with business was as a clerk with his father, who kept a store at the corner of Church and Market streets, to which, in due course of time, Mr. Oakes, the subject of the sketch, succeeded as proprietor."[7] Circa 1823, Samuel Oakes advertised the newly opened Milton's ferry from Fitzsimons' Wharf to Christchurch in Georgetown, as well as an accompanying ferry tavern.[8]

Around 1826, Samuel Oakes bought, from Mr. N. Very, a grocery that specialized in sugar, coffee, tea and chocolate.[9] Circa 1827, when he about 20 years old, "Z.T. Oakes" applied for a license to "retail Spirituous Liquors" at the establishment of Samuel Oakes located at 117 Broad.[10] On February 24, 1831, Ziba Oakes married Margaret Christie (1813–1886).[11] In 1833 Samuel Oakes & Son advertised five cases of "satin beaver hats" newly arrived on the barque Chief, as "fashionable, waterproof, and warranted to retain their color...for sale, low."[12] On October 1, 1834, father Samuel Oakes and son Z.B. Oakes dissolved their legal partnership.[13] Also in 1834, Oakes was the manager of the election of officers for the Marion Riflemen, Second Battalion, 16th Regiment Infantry, South Carolina Militia, which was assigned to a beat along the Cooper River.[14] Oakes sold a "mulatto slave named Richard" for $500 (~$14,184 in 2022) in December 1835.[15]

Trading career

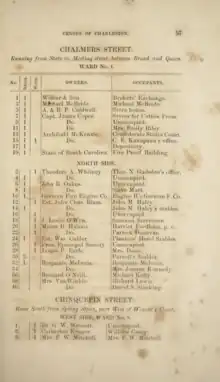

On February 6, 1843, Oakes placed a notice in the Charleston Daily Courier formally announcing a new business enterprise opening on State Street: "The Subscriber respectfully informs his friends and the public that he has commenced the BROKERAGE AUCTION and COMMISSION BUSINESS at No 7 State-street. He will attend to the purchase and sale of Real Estate, Negroes, Stocks &c; and hopes by proper attention to business to merit a share of public patronage Liberal advances at all times made on property placed in his possession for sale. Z. B. Oakes."[16] According to Michael Tadman, Oakes "specialised in selling slaves to long-distance traders...Ziba Oakes's trading arrangements relied essentially upon a quick turn-over of capital." In exchange for being able to rapidly assemble a shipping lot of enslaved people, Oakes' trading partners were apparently willing to pay a slight premium.[17]

In 1844, the father, Samuel Oakes, was implicated in a case of illegally importing four people across state lines into Georgia,[18] which at that time prohibited interstate slave trading (the prohibition was repealed in 1856).[19]

In 1850 Z.B. Oakes shared a home with his mother, his wife (the former Margaret Garaux Christie),[20] and their four daughters; his occupation was broker.[21] Broker, rather than trader or slave trader, was the term commonly used in Charleston to describe slave traders.[22] Like a dozen other Charleston slave traders, he initially had his offices on State Street.[23] In December 1850, Z.B. Oakes, formerly of the Sugar Store, and now broker and auctioneer at 7 State street offered, "CONFECTIONER AT PRIVATE SALE A very intelligent FELLOW a complete Confectioner probably the best of his color in the State. Apply to Z. B. OAKES."[24] Oakes was one of about 50 known slave traders operating in Charleston in the 1850s.[25] According to Frederic Bancroft, Oakes was no more than a mid-level trader in the Charleston slavery economy.[26] In 1856, along with fellow slave traders Louis D. DeSaussure and Alonzo J. White, he opposed a new South Carolina law requiring that slave sales take place indoors rather than on the streets. Their argument was that the law was "an impolitic admission that would give 'strength to the opponents of slavery' and 'create among some portions of the community a doubt as to the moral right of slavery itself.'"[27]

A 2020 biography claimed that by 1860 Oakes "was the most prosperous of Charleston's approximately 40 slave traders."[28] In 1860, on the eve of the American civil war, his occupation was again listed as broker, and he owned real estate valued at US$42,000 (equivalent to $1,367,956 in 2022), and he had a personal estate valued at US$50,000 (equivalent to $1,628,519 in 2022).[29] In the 1861 Charleston city directory, Z.B. Oakes lived at 59 Beaufain, and his slave mart was located at 7 and 9 Chalmers.[30]

In May 1862, the Charleston Mercury apprised its readership of the current state of the local market in human beings: "SALE OF NEGROS—Mr. Z. B. Oakes, broker, at private sale, a gang of thirty negroes for $17,500, an average of $583.33."[31] If Oakes took the standard 2.5 percent broker commission his share of the US$17,500 (equivalent to $512,983 in 2022) would have been US$437.50 (equivalent to $12,825 in 2022).[32] Oakes was listing slaves for sale as late as November 1864: "A GANG OF 75 NEGROES accustomed to the culture of Rice, Cotton and Provisions. Amongst them are a capable and Intelligent Driver and a good Carpenter. These Negroes have worked together as a gang for many years and are orderly and efficient."[33] Oakes' last known advertisement for an enslaved person appeared in the Charleston Mercury of November 9, 1864: "A likely young man, a superior cook in all branches of the trade, apply as above."[34] Oakes served in the Confederate States Army as a private in Company C of the 1st Regiment, South Carolina Militia (Charleston Reserves).[35]

Post-bellum and later life

In February 1865, journalist Charles Carleton Coffin visited the mart:[36]

I entered the Theological Library building through a window from which General Gillmore had removed the sash by a solid shot. A pile of old rubbish lay upon the floor, — sermons, tracts, magazines, books, papers, musty and mouldy, turning into pulp beneath the rain-drops which came down through the shattered roof. ¶ Amid these surroundings was the Slave-Mart, — a building with a large iron gate in front, above which, in large gilt letters, was the word MART. The outer iron gate opened into a hall about sixty feet long by twenty broad, flanked on one side by a long table running the entire length of the hall, and on the other by benches. At the farther end a door, opening through a brick wall, gave entrance to a yard. The door was locked. I tried my boot-heel, but it would not yield. I called a freedman to my aid. Unitedly we took up a great stone, and gave a blow. Another, and the door of the Bastile went into splinters. Across the yard was a four-story brick building, with grated windows and iron doors, — a prison. The yard was walled by high buildings. He who entered there left all hope behind. A small room adjoining the hall was the place where women were subjected to the lascivious gaze of brutal men. There were the steps, up which thousands of men, women, and children had walked to their places on the table, to be knocked off to the highest bidder...While there a colored woman came into the hall to see the two Yankees. ¶ "I was sold there upon that table two years ago," said she. "You never will be sold again; you are free now and forever," I replied. "Thank God! the blessed Jesus, he has heard my prayer. I am so glad; only I wish I could see my husband. He was sold at the same time into the country, and has gone I don't know where." Thus spake Dinah Moore. ¶ Entering the brokers' offices, — prisons rather, — we walked along the grated corridors, looked into the rooms where the slaves had been kept. In the cellar was the dungeon for the refractory, — bolts and staples in the floors, manacles for the hands and feet, chains to make all sure. There had evidently been a sudden evacuation of the premises. Books, letters, bills of sale, were lying on the floor. ¶ Let us take our last look of the Divine missionary institution. Thus writes James H. Whiteside to Z. B. Oakes: — "I know of five very likely young negroes for sale. They are held at high prices, but I know the owner is compelled to sell next week, and they may be bought low enough so as to pay. Four of the negroes are young men, about twenty years old, and the other a very likely young woman about twenty-two. I have never stripped them, but they seem to be all right."

Tadman describes the letters to Ziba Oakes collected by activist and journalist James Redpath at the end of the war as being of "great importance" in the study of the final decade of the South Carolina slave trade.[17] In 1866, Oakes was back to work, continuing as an auctioneer and a broker of real-estate, and now offering insurance for "lives, cotton in transit and store, merchadize, buildings, and all other insurable interests."[37] He was elected a supervisor of the high school in 1866.[38] He was also a commissioner of the alms house, and a commissioner of markets, and was elected alderman from 1865 to 1868; "the notion that slave traders were looked down upon by the South's elite is contradicted by the prominent role Oakes played in Charleston society."[28] At the time of the 1870 federal census Oakes' youngest daughter, still living at home, was 17 years old, and there are six other members of the household: Richard Morris (domestic servant), Eliza Brown (cook), Elizabeth Sinclair (laundress), are all listed as black, native to South Carolina; 13-year-old Rose Leggerman is listed as mulatto, native to South Carolina, with no listed occupation; Gus May, 35, and Edward May, 14, have no occupations listed, and are listed as black, native of South Carolina.[39]

Death and legacy

Ziba Oakes was an active member of his community who participated in a number of fraternal organizations.[40] He died at the age of 63 years, 11 months, and is buried in Charleston's Magnolia Cemetery.[41] His obituary made the front page of the newspaper.[7]

As part of what was the apparently common practice of scrubbing "clean the records of...leading South Carolina slave dealers," the newspaper that printer Oakes obituary reported that he "had made his money 'in the Commission and Auction business,' but it failed to mention that much of that business had involved buying and selling people, or that Oakes had once owned Ryan's Mart."[42] This kind of intentional forgetting was typical and persisted into the 20th century: "Despite Wilson's insistence that [6 Chalmers] had been associated with the internal American slave trade, many locals disparaged her claim. Of course, rendering the domestic slave trade invisible was a central aspect of the postbellum white South's reconstruction of its history and its promotion of an apologist's view of slavery. Tourist literature from early-twentieth-century Charleston was complicit in this process as it repeatedly denied the existence of slave markets in the city. C. Irvine Walker's 1919 Guide to Charleston. S.C. downplayed the practice of slave sales, describing them as uncommon though "necessary from time to time." Tourists were told that, for the most part, slaves were 'passed by inheritance from father to son.' Walker frankly attributed claims that the property on Chalmers Street was the 'Old Slave Market, so-called,' to that 'same partisan history which stigmatizes the institution of slavery.' A headline in 1930 in the Charleston News and Courier articulated further the local position: 'Building at 6 Chalmers Street Has Become Subject of Legend in City.'...the News and Courier reporter erroneously argued that the site could not have been a slave mart because there was never 'sufficient buying and selling of slaves in the city to have warranted the establishment of any institution for the purpose.'"[43]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Yuhl (2013), p. 598.

- 1 2 Hicks, Brian (2011-04-09). "Slavery in Charleston: A chronicle of human bondage in the Holy City". Post and Courier. Retrieved 2023-07-15.

- ↑ Bancroft (2023), p. 121.

- 1 2 3 Campbell, Edward D. C. (1992). ""Broke by the War": Letters of a Slave Trader (review)". Civil War History. 38 (3): 265–266. doi:10.1353/cwh.1992.0025. ISSN 1533-6271. S2CID 144081664.

- ↑ "Ziba B. Oakes Papers, 1852-1857 - Digital Commonwealth". www.digitalcommonwealth.org. Retrieved 2023-07-15.

- 1 2 3 Oak, Henry Lebbeus (1906). Oak--Oaks--Oakes: family register, Nathaniel Oak of Marlborough, Mass., and three generations of his descendants in both male and female lines. New England Historic Genealogical Society. Los Angeles: Out West Co. Print. pp. 37–38 – via HathiTrust.

- 1 2 "Article clipped from The Charleston Daily News". The Charleston Daily News. 1871-05-27. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ↑ "New Ferry to Georgetown". The Charleston Daily Courier. 1823-12-04. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ "Sugar, tea, coffee, and chocolate". The Charleston Daily Courier. 1826-11-08. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ "Council Chamber, November 24th, 1827". The Charleston Mercury. 1827-11-27. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ "South Carolina, U.S., Compiled Marriage Index, 1641-1965". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ↑ "Satin Beaver Hats". The Charleston Daily Courier. 1833-12-03. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ "Oakes partnership dissolved". The Charleston Daily Courier. 1834-10-08. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ "Brigade Order, Fourth Brigade, 2nd Division, So. Ca. Militia". The Charleston Mercury. 1834-03-31. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ "Z B Oakes, 2 Dec 1835; citing Court, Charleston, South Carolina, United States, Records Of The Secretary Of State, Recorded Instruments, Miscellaneous Records (Main Series), Bills Of Sale Volumes, 793, South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia", South Carolina, Charleston District, Bill of sales of Negro slaves, 1774-1872 – via FamilySearch

- ↑ "Notice". The Charleston Daily Courier. 1843-02-06. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- 1 2 Tadman, Michael (November 1977). Speculators and Slaves in the Old South: A Study of the American Domestic Slave Trade, 1820-1860 (PDF). University of Hull (Thesis). p. 108 (letters), 113–114 (business). Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ↑ "Proceedings of the Council, Savannah, Thursday, May 30, 1844". The Charleston Daily Courier. 1844-06-04. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ "Slave Laws of Georgia, 1755–1860" (PDF). georgiaarchives.org. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ↑ Daughters of the American Revolution (1905). Lineage Book. The Society. p. 343.

- ↑ "Entry for Z B Oakes and Margaret G Oakes, 1850", United States Census, 1850 – via FamilySearch

- ↑ Bancroft (2023), pp. 173–174.

- ↑ Bancroft (2023), p. 185.

- ↑ "Confectioner at Private Sale". The Charleston Daily Courier. 1850-12-21. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ Bancroft (2023), pp. 175.

- ↑ Bancroft (2023), pp. 185–186.

- ↑ Kytle & Roberts (2018), pp. 34–35.

- 1 2 Carey, Charles (2020-03-01). American Inventors, Entrepreneurs, and Business Visionaries, Revised Edition. Infobase Holdings, Inc. pp. 283–284. ISBN 978-1-4381-8214-8.

- ↑ "Entry for Z B Oakes and Margaret Oakes, 1860", United States Census, 1860 – via FamilySearch

- ↑ "Census of the City of Charleston, South Carolina, For the Year 1861. Illustrated by Statistical Tables. Prepared under the Authority of the City Council by Frederick A. Ford [Electronic Edition]". docsouth.unc.edu. Charleston (S.C.). City Council. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ↑ "Gang of Negroes". The Charleston Mercury. 1862-05-31. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ Bancroft (2023), p. 174.

- ↑ "Prime Gang of Negroes, accustomed to the culture of Rice, Cotton and Provisions, by Z. B. Oakes". The Charleston Mercury. 1864-11-05. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ "Superior Male Cook, at Private Sale". The Charleston Mercury. 1864-11-09. p. 2. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ National Park Service. "U.S., Civil War Soldiers, 1861-1865". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ↑ Coffin, Charles Carleton (1885). The boys of '61; or, Four years of fighting. Boston: Estes and Lauriat. pp. 473–475 – via HathiTrust.

- ↑ "Z. B. Oakes". The Charleston Daily Courier. 1866-04-18. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ "City Council, Dec. 11, 1866". The Charleston Daily News. 1866-12-13. p. 1. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ "Tiba Oakes, 1870", United States Census, 1870 – via FamilySearch

- ↑ "The Charleston Daily News 27 May 1871, page Page 2". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ↑ "L B Oakes, 1871", South Carolina, Charleston City Death Records, 1821-1926 – via FamilySearch

- ↑ Kytle & Roberts (2018), pp. 272–273.

- ↑ Yuhl (2013), p. 602.

Sources

- Bancroft, Frederic (2023) [1931]. Slave Trading in the Old South. Southern Classics Series. Introduction by Michael Tadman. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-64336-427-8.

- Kytle, Ethan J.; Roberts, Blain (2018). Denmark Vesey's garden: slavery and memory in the cradle of the Confederacy. New York: The New Press. ISBN 9781620973660. LCCN 2017041546.

- Yuhl, Stephanie E. (2013). "Hidden in Plain Sight: Centering the Domestic Slave Trade in American Public History". The Journal of Southern History. 79 (3): 593–624. ISSN 0022-4642. JSTOR 23795089.

Further reading

- McElveen, A. J.; Oakes, Ziba B. (2010). Drago, Edmond Lee (ed.). Broke by the War: Letters of a Slave Trader. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1570039423.