This is a list of Christian women in the patristic age who were leaders and members of the early Christian churches and communities. The list is roughly in chronological order of year when they lived or died. The patristic era is considered to have started at the end of the 1st century and to have ended towards the close of the 7th century.[1]

The description column uses the historical, literary or archeological evidence (such as letters, inscriptions, texts and funerary art) to summarise women's contribution to the early church and their legacy. As far as possible, historical sources are used rather than hagiography. The position, titles, status or "also known as" are listed in the first column under the woman's name. Some were referred to during their life as deacons, presbyters, ministers, martyrs, Empress or Augusta. Later they may have been called church patrons, teachers, leaders, church mothers, Desert Mothers, martyrs or saints.[2][3]

There is a link in the woman's name to her Wikipedia page or one mentioning her. Readers can go to the linked page to read more life details and about any churches who may venerate her.

| Name, also known as | Year(s) lived | Image | Location | Description and legacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two slave women deacons

Ministers, deaconesses, maid-servants |

Pliny's letter c 112 |  |

Bithynia | The governor, Pliny the Younger, wrote a letter to Emperor Trajan; one of the earliest documents showing persecution of the church by Roman authorities. Pliny wrote he had ordered the torture of two slave women called "ministers" or "deacons" to find out about Christian beliefs and practices. Their legacy was that they revealed the early church met together to sing hymns, vowed to live moral lives and practised a spiritual equality between men and women, slave-owners and slaves that was counter-cultural to the patriarchal and socially stratified Roman society. [4][5][6][7][8][2] |

| Ammia of Philadelphia | c 100-160 | Philadelphia (now Alaşehir in Turkey), Asia Minor | Ammia was mentioned by Eusebius as a renowned prophet, a successor to the apostles, with the same status as the prophets Phillip's daughters and Agabus (Acts 21) and later Quadratus.[9][10][11] | |

| Blandina

Maid of Lyon, Martyr of Lyon, saint, virgin |

d 177[12] | _bpt6k6350834v-1.jpg.webp) |

Lyon | Blandina was a Christian slave girl, one of the martyrs of Lyon, who was tortured, exposed to wild animals, tied to a stake in the arena and finally killed for her faith. She encouraged and strengthened a fellow martyr, the teenage boy Ponticus.[13] For the onlookers, Blandina was inspirational and persuasive, modelling endurance, Christ-likeness and personal spiritual power in withstanding powerful authorities [14] even though she was a young woman and a slave with no social or legal status.[15][3][12] |

| Agatha of Sicily

virgin, martyr |

Sicily | Agatha of Scily was a virgin and martyr venerated as a saint in Roman Catholic tradition. She was tortured to death by Quintianus. | ||

| Cecilia of Rome

virgin, martyr |

177[16] | .JPG.webp) |

Rome | Cecilia was a noble lady of Rome who was martyred after her husband Valerian, his brother Tiburtius, and a Roman soldier named Maximus.[17] After their deaths, Cecilia collected their bones and buried them, then preached and evangelised to many people in Rome. She was executed for preaching and practising Christianity.[18] |

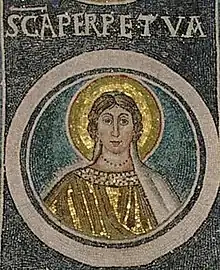

| Perpetua

Saint |

203[19] |  |

Carthage | Perpetua was arrested with Saint Felicitas, Saturnius, Revocatus, and Secundulus. Perpetua and her companions are examples of those who would not deny being a Christian despite being placed in gladitorial/animal shows.[20] While in prison, she gave birth to a son and put him into the care of others.[19] |

| Felicitas

Saint |

203[19] | _(14597219839).jpg.webp) |

Carthage | Felicitas was arrested along with Saint Perpetua and others and placed in gladiatorial/animal shows. She did not deny being a Christian.[20] She was pregnant when she was arrested. In jail, she gave birth at eight months to a girl who was given to 'sisters' to raise.[21] |

| Lucy | 304[22] |  |

Syracuse, Sicily | Lucy worked with the poor and those confined to their homes by bringing them food. She is also thought to have done the same for those Christians hiding in the catacombs.[23][20] |

| Agnes of Rome

virgin martyr, saint |

304[24] |  |

Rome | Twelve year old Agnes was a Christian from a noble family but asked to marry the Roman son of a city official. She informed him that her fiancé was Jesus Christ. She was subsequently executed by a sword. She was a model for chastity and commitment to Christ.[20][25] |

| Paula of Rome

Saint, Desert Mother, wealthy widow |

Lived 347-404[3] |  |

Rome and Bethlehem | Paula of Rome was a widowed Roman noblewoman, disciple and friend of Jerome, who became an ascetic bible scholar and abbess. At Bethlehem, she established a double monastery and hostel for pilgrims. Paula memorised scripture, sang the psalms,[26] was fluent in Greek and Hebrew and acted as patron, financing Jerome's translation of the bible into Latin, now known as the Latin Vulgate bible.[27][3][28] Jerome dedicated many of his commentaries and books to her.[28] |

| Macrina the Younger

Saint, consecrated virgin |

379[29] |  |

Cappadocia | Macrina was intelligent and educated. After her fiancé died suddenly when she was twelve, she vowed not to marry. She took care of her family and supported them after her father died. She was influential in the education of Bishop Peter of Sebaste, St. Gregory, and Basil of Caesarea who were her brothers. She also established a religious community and became its head.[29][30] |

| Catherine of Alexandria | early 4th century[31][32] |  |

Alexandria | Catherine of Alexandria was a saint who was martyred in the early 4th century by Maxentius. She was both a princess and a noted scholar, who became a Christian around the age of 14, converted hundreds of people to Christianity, and was martyred around the age of 18. More than 1,100 years following her martyrdom, Saint Joan of Arc identified Catherine as one of the saints who appeared to her and counselled her.[33] |

| Helena

Empress, Augusta, Helena of Constantinople |

est. lived 248-326/27[3] |  |

Trier and Rome[34] | Helena was the Empress of the Roman Empire (consort of the future Roman Emperor Constantius Chlorus who reigned 293–306) and mother of Emperor Constantine the Great. Constantine proclaimed her Helena "Augusta", a title of imperial influence. She made a pilgrimage to Palestine and the eastern provinces where she supervised the building of churches on his behalf and supported Christians to freely practise their religion.[3][34] |

| Olympias

the younger, deaconness, saint |

361-408[35] |  |

Constantinople | Olympias was a wealthy widow who donated her inheritance to the church and the poor, founded and led a monastery, built a hospital and orphanage, was friends with John Chrysostom, Gregory Nazianzen, and Gregory of Nyssa. Her piety impressed Emperor Theodosius. She was ordained a deaconess by Nectarius, Archbishop of Constantinople. [35][36][37][38][39] |

| Monica | 387[40] |  |

Alexandria | Monica had great influence over the development of her son Saint Augustine's faith. It was her prayerful life that influenced the conversion of Augustine who wrote about her extensively in his book Confessions.[41][40] Augustine and his friends would gather for discussions on philosophy and he would ask Monica to join in the discussions.[42] She also was known for her charitable works.[43] |

| Fabiola

saint, nurse, hospital founder |

d. 399[44] |  |

Rome and Bethlehem | From a wealthy Roman family, Fabiola became a widow to her second husband, repented of her past life and devoted herself and her wealth to the church, helping the poor and sick. She founded a hospital in Rome (and a pilgrim's hospice) where she personally treated patients and for a time lived an ascetic life and studied scripture with Paula and Jerome in Bethlehem, nursing in their hospice. She became a role model for Christian women to provide medical aid to people living in poverty. [18][45][44] |

| Fritigil

Queen Fritigil of the Marcomanni |

c397, mid 4th century |  |

Marcomanni, Austria, Czech Republic | Fritigil corresponded with Ambrose, Bishop of Milan, converted to Christianity, persuaded her husband (presumed king) to convert and to make peace with the Romans, travelled to Milan to meet Ambrose but he died before she reached him. Little else is known about her but that she exercised political and spiritual authority and led her people into Christianity.[46][47][48][49] |

| Aelia Pulcheria

Augusta |

Lived 399-c453[3] |  |

Constantinople | Pulcheria was daughter to Emperor Arcadius and Empress Eudoxia, and sister to Theodosius II for whom she acted as regent and guardian. Pulcheria committed herself to Christianity and virginity at a young age and ensured the future Emperor Theodosius II was tutored in the Christian faith. She built three churches in Constantinople, was friend to the archbishops/patriarchs of Constantinople and Pope Leo I and a patron to monastic communities. She was influential in both imperial and church politics and helped convene and guide the Council of Ephesus and the Council of Chalcedon.[3] |

| Cerula and Bitalia | Mid 400s? | Leaders and teachers in the early church in Naples, Italy. Because of their depictions in a fresco above tombs, it has been speculated they could have been bishops.[50][51] |

See also

References

- ↑ "Glossary Definition: Patristic Era". PBS. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- 1 2 Osiek, Carolyn; Madigan, Kevin, eds. (2005). Ordained women in the early church : a documentary history. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0157-7. OCLC 794700384.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Cohick, Lynn H.; Hughes, Amy Brown (2017). Christian women in the patristic world : their influence, authority, and legacy in the second through fifth centuries. Grand Rapids, MI. ISBN 978-0-8010-3955-3. OCLC 961154751.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Cohick, Lynn H. (2009). Women in the world of the earliest Christians : illuminating ancient ways of life. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4412-0799-9. OCLC 727647610.

- ↑ "On Pliny and the two female slaves - Centre for Public Christianity". www.publicchristianity.org. 2020-03-05. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ↑ Hall, Stuart George (1992). Doctrine and practice in the early church. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0629-5. OCLC 25273636.

- ↑ Pliny, Ep. X.96

- ↑ Stevenson, James, ed. (2013). A New Eusebius : documents illustrating the history of the church to AD 337 (Rev. / by W.H.C. Frend ed.). Grand Rapids, Michigan. ISBN 978-0-8010-3971-3. OCLC 848067412.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Eisen, Ute E.. Women officeholders in early Christianity : epigraphical and literary studies. United States, Liturgical Press, 2000.

- ↑ "Philip Schaff: NPNF2-01. Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". www.ccel.org. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ↑ Kidson, Lyn (2018-05-28). "Ammia in Philadelphia". engendered ideas. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- 1 2 "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Blandina". newadvent.org. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ↑ "23 The Martyrs of Lyons and Vienne". A New Eusebius : documents illustrating the history of the church to AD 337. James Stevenson (Rev. / by W.H.C. Frend ed.). Grand Rapids, Michigan. 2013. ISBN 978-0-8010-3971-3. OCLC 848067412.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Goodine, Elizabeth A.; Mitchell, Matthew W. (2005). "The Persuasiveness of a Woman: The Mistranslation and Misinterpretation of Eusebius' Historia Ecclesiastica 5.1.41" (PDF). Journal of Early Christian Studies. 13 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1353/earl.2005.0007. ISSN 1086-3184. S2CID 170533021.

- ↑ Goodine, Elizabeth A. (2014). Standing at Lyon : an examination of the martyrdom of Blandina of Lyon. [Place of publication not identified]. ISBN 978-1-4632-0384-9. OCLC 884300187.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Cecilia". saintsresource.com. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- ↑ Fuller, Osgood Eaton: Brave Men and Women. BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2008, page 272. ISBN 0-554-34122-0

- 1 2 Denzey Lewis, Nicola (2007). The bone gatherers : the lost worlds of early Christian women. Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-1308-3. OCLC 76939881.

- 1 2 3 "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Sts. Felicitas and Perpetua". newadvent.org. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- 1 2 3 4 Plassman, Thomas; Vann, Joseph. Lives of Saints with Excerpts From Their Writings. John J. Crawley and Co., Inc. pp. 11, 28, 29, 40, and 42.

- ↑ "The Martyrdom Of Saints Perpetua And Felicitas | From Jesus To Christ". FRONTLINE. PBS. Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- ↑ "Saint Lucy". Franciscan Media. 2015-12-13. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- ↑ "About Saint Lucy". St. Lucy Catholic Parish. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- ↑ "Who Was Saint Agnes?". The Church of Saint Agnes. Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- ↑ "Agnes of Rome". Visual Museum. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

- ↑ Jerome, Letter XLV. To Asella.

- ↑ "Philip Schaff: NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome - Christian Classics Ethereal Library". ccel.org. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- 1 2 Saint Jerome (2013). Cain, Andrew (ed.). Jerome's epitaph on Paula : a commentary on the Epitaphium Sanctae Paulae. Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-967260-8. OCLC 835969199.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Macrina the Younger". newadvent.org. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ↑ "Macrina of Cappadocia, sister of holy hierarchs Basil the Great and Gregory of Nyssa, venerable | RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CATHEDRAL OF ST.JOHN THE BAPTIST". stjohndc.org. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ↑ "St. Catherine of Alexandria | Egyptian martyr". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- ↑ "St. Catherine of Alexandria". nndb.com. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- ↑ Williard Trask, Joan of Arc: In Her Own Words (Turtle Point Press, 1996), 99

- 1 2 Drijvers, Jan Willem (1992). Helena Augusta : the mother of Constantine the Great and the legend of her finding of the true cross. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-09435-0. OCLC 23766374.

- 1 2 "St. Olympias". faith.nd.edu. Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- ↑ "Olympias: Deaconess and Chrysostom's Friend". Marg Mowczko. 2019-07-25. Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- ↑ "CHURCH FATHERS: Ecclesiastical History, Book VIII (Sozomen)". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- ↑ "The Dialogue of Palladius concerning the Life of St. John Chrysostom (1921). English translation". www.tertullian.org. Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- ↑ "John Chrysostom & Olympias: Soul Friends by Ron Dart". Clarion: Journal of Spirituality and Justice. Retrieved 2023-01-07.

- 1 2 Coffman, Elesha. "Faith of Our Mothers". Christian History | Learn the History of Christianity & the Church. Retrieved 2019-04-16.

- ↑ "St. Monica Catholic Church". stmonicaindy.org. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- ↑ "St. Monica". Midwest Augustinians. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- ↑ "St. Monica". ewtn.com. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- 1 2 "Saint Fabiola." World of Health, Gale, 2006. Gale In Context: Biography, link.gale.com/apps/doc/K2191100118/BIC?u=wikipedia&sid=ebsco&xid=9e12196f. Accessed 28 Dec. 2022.

- ↑ H. Wendell Howard. (2011). Saint Fabiola in Fiction, in History, in Portraiture. Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture, 14, 82–95. doi:10.1353/log.2011.0014

- ↑ "Fritigil, markomannische Königin (english)". Austria-Forum (in German). 2022-12-28. Retrieved 2022-12-28.

- ↑ Butler, Alban. The Lives of the Fathers, Martyrs, and Other Principal Saints: Compiled from Original Monuments and Other Authentic Records, Illustrated with the Remarks of Judicious Modern Critics and Historians. United Kingdom, J. Murphy, 1813.

- ↑ Kessler, P. L. "Kingdoms of the Germanic Tribes - Marcomanni (Suevi)". The History Files. Retrieved 2022-12-28.

- ↑ Athanasius, et al. Early Christian Biographies. United States, Catholic University of America Press, 2010.

- ↑ "Cerula and Bitalia – Women Bishops? – Women Deacons". www.womendeacons.org. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

- ↑ Ally Kateusz. (2021). Mary and early Christian women: Hidden Leadership. p156.