Selected articles covering the Mesozoic and the natural world

The exposed geology of the Death Valley area presents a diverse and complex set of at least 23 formations of sedimentary units, two major gaps in the geologic record called unconformities, and at least one distinct set of related formations geologists call a group. The oldest rocks in the area are extensively metamorphosed by intense heat and pressure and are at least 1700 million years old. These rocks were intruded by a mass of granite 1400 Ma (million years ago) and later uplifted and exposed to nearly 500 million years of erosion.

Marine deposition occurred 1200 to 800 Ma, creating thick sequences of conglomerate, mudstone, and carbonate rock topped by stromatolites, and possibly glacial deposits from the hypothesized Snowball Earth event. Rifting thinned huge roughly linear parts of the supercontinent Rodinia enough to allow sea water to invade and divide its landmass into component continents separated by narrow straits. A passive margin developed on the edges of these new seas in the Death Valley region. Carbonate banks formed on this part of the two margins only to be subsided as the continental crust thinned until it broke, giving birth to a new ocean basin. An accretion wedge of clastic sediment then started to accumulate at the base of the submerged precipice, entombing the region's first known fossils of complex life. These sandy mudflats gave way about 550 Ma to a carbonate platform which lasted for the next 300 million years of Paleozoic time. (see more...)

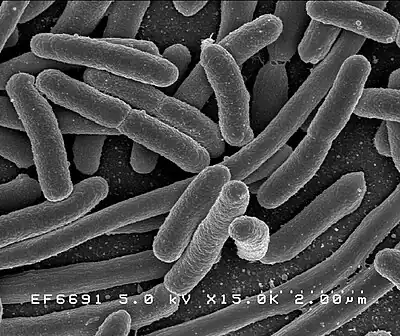

The Archaea show many differences in their biochemistry from other forms of life, and so they are now classified as a separate domain in the three-domain system. So far, the Archaea have been further divided into four recognized phyla. Classification is still difficult, because the vast majority have never been studied in the laboratory.

Archaea and bacteria are quite similar in size and shape, but despite this visual similarity to bacteria, archaea possess genes and several metabolic pathways that are more closely related to those of eukaryotes. Other aspects of archaean biochemistry are unique, such as their reliance on ether lipids in their cell membranes. Archaea use a much greater variety of sources of energy than eukaryotes: ranging from familiar organic compounds such as sugars, to ammonia, metal ions or even hydrogen gas. Salt-tolerant archaea use sunlight as an energy source, and other species of archaea fix carbon. Archaea reproduce asexually by binary fission, fragmentation, or budding.

Archaea are found in a broad range of habitats, includingsoils, oceans, marshlands and the human colon and navel. Archaea are now recognized as a major part of Earth's life and may play roles in both the carbon cycle and the nitrogen cycle. (see more...)

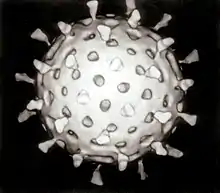

Virus particles (known as virions) consist of two or three parts: i) the genetic material made from either DNA or RNA, long molecules that carry genetic information; ii) a proteincoat that protects these genes; and in some cases iii) an envelope of lipids that surrounds the protein coat when they are outside a cell. The shapes of viruses range from simplehelical and icosahedral forms to more complex structures. The average virus is about one one-hundredth the size of the average bacterium.

The origins of viruses in the evolutionary history of life are unclear: some may have evolved from plasmids—pieces of DNA that can move between cells—while others may have evolved from bacteria. Viruses are considered by some to be a life form, because they carry genetic material, reproduce, and evolve through natural selection. However they lack key characteristics (such as cell structure) that are generally considered necessary to count as life, so whether or not viruses are truly alive is controversial. (see more...)

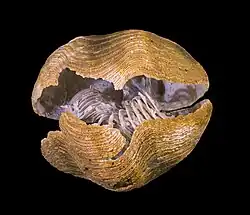

The shell of a bivalve is composed of calcium carbonate, and consists of two, usually similar, parts called valves. These are joined together along one edge by a flexible ligament that, in conjunction with interlocking "teeth" on each of the valves, forms the hinge. The shell is typically bilaterally symmetrical, with the hinge lying in the sagittal plane. Adult shell sizes vary from fractions of a millimetre to over a metre in length, but the majority of species do not exceed 10 cm (4 in).

Bivalves appear in the fossil record first in the early Cambrian more than 500 million years ago. The total number of living species is approximately 9,200. These species are placed within 1,260 genera and 106 families. Marine bivalves (including brackish water and estuarine species) represent about 8,000 species, combined in four subclasses and 99 families with 1,100 genera. The largestrecent marine family is the Veneridae, with more than 680 species. (see more...)

Like their exteriors, the internal organs of arthropods are generally built of repeated segments. Their vision relies on various combinations of compound eyes and pigment-pit ocelli. Arthropods also have a wide range of chemical and mechanical sensors, mostly based on modifications of the many setae (bristles) that project through their cuticles. Nearly all arthropods lay eggs. Arthropod hatchlings vary from miniature adults to grubs and caterpillars that lack jointed limbs and eventually undergo a total metamorphosis to produce the adult form.

The evolutionary ancestry of arthropods dates back to the Cambrian period. The group is generally regarded as monophyletic, and many analyses support the placement of arthropods with cycloneuralians (or their constituent clades) in a superphylum Ecdysozoa. Overall however, the basal relationships of Metazoa are not yet well resolved. Likewise, the relationships between various arthropod groups are still actively debated. (see more...)

The existing bedrock includes very ancient Archean gneiss, metamorphic beds interspersed with granite intrusions created during the Caledonian mountain building period (the Caledonian orogeny), commercially important coal, oil and iron bearing carboniferous deposits and the remains of substantial Paleogene volcanoes. During their formation, tectonic movements created climatic conditions ranging from polar to desert to tropical and a resultant diversity of fossil remains.

Scotland has also had a role to play in many significant discoveries such as plate tectonics and the development of theories about the formation of rocks and was the home of important figures in the development of the science including James Hutton, (the "father of modern geology") Hugh Miller and Archibald Geikie. Various locations such as 'Hutton's Unconformity' at Siccar Point in Berwickshire and the Moine Thrust in the north west were also important in the development of geological science. (see more...)

Starfishes typically have a central disc and five arms, though some species have more than this. The aboral or upper surface may be smooth, granular or spiny, and is covered with overlapping plates. Starfish have tube feet operated by a hydraulic system and a mouth at the centre of the oral or lower surface. They are opportunistic feeders and are mostly predators on benthicinvertebrates. Several species having specialized feeding behaviours including eversion of their stomachs and suspension feeding. They have complex life cycles and can reproduce both sexually and asexually. Most can regenerate damaged parts or lost arms and they can shed arms as a means of defence. The Asteroidea occupy several significant ecological roles.

The fossil record for starfish is ancient, dating back to the Ordovician around 450 million years ago, but it is rather poor, as starfish tend to disintegrate after death. Only the ossicles and spines of the animal are likely to be preserved, making remains hard to locate. (see more...)

Chelicerates were originally predators, but the group has diversified to use all the major feeding strategies. The guts of most modern chelicerates are too narrow for solid food, and they generally liquidize their food by grinding it with their chelicerae and pedipalps and flooding it with digestive enzymes. Most lay eggs that hatch as what look like miniature adults. In most chelicerate species the young have to fend for themselves, but in scorpions and some species of spider the females protect and feed their young.

The chelicerata originated as marine animals, possibly in the Cambrian period, but the first confirmed chelicerate fossils, eurypterids, date from 445 million years ago in the Late Ordovician period.

The surviving marine species include the four species of xiphosurans (horseshoe crabs), and possibly the 1,300 species of pycnogonids (sea spiders), if the latter are chelicerates. (see more...)%252C_plate_82.jpg.webp)

It is estimated that there are about 9000 species of liverworts. Some of the more familiar species grow as a flattened leafless thallus, but most species are leafy with a form very much like a flattenedmoss. Leafy species can be distinguished from the apparently similar mosses on the basis of a number of features, including their single-celled rhizoids. Leafy liverworts also differ from most (but not all) mosses in that their leaves never have a costa and may bear marginal cilia (very rare in mosses). Other differences are not universal for all mosses and liverworts, but the occurrence of leaves arranged in three ranks, the presence of deep lobes or segmented leaves, or a lack of clearly differentiated stem and leaves all point to the plant being a liverwort.

Liverworts are typically small, usually from 2–20 mm wide with individual plants less than 10 cm long, and are therefore often overlooked. However, certain species may cover large patches of ground, rocks, trees or any other reasonably firm substrate on which they occur. They are distributed globally in almost every available habitat, most often in humid locations although there are desert and arctic species as well. (see more...)

The life cycles of insects vary but most insects hatch from eggs. Insect growth is constrained by the inelastic exoskeleton and development involves a series of molts. The immature stages can differ from the adults in structure, habit and habitat. Insects that undergoincomplete metamorphosis lack a pupal stage and adults develop through a series of nymphal stages. Fossilized insects of enormous size have been found from the Paleozoic Era, including giant dragonflies with wingspans of 55 to 70 cm (22–28 in). The most diverse insect groups appear to have coevolved with flowering plants.

Adult insects typically move about by walking, flying, or sometimes swimming. Insects are the only invertebrates to have evolved flight. Many insects spend at least part of their lives under water, with larval adaptations that include gills, and some adult insects are aquatic and have adaptations for swimming. Insects are mostly solitary, but some, such as certain bees, ants and termites, are social and live in large, well-organized colonies. (see more...)

The geology of the Zion and Kolob canyons area includes nine known exposed formations, all visible in Zion National Park in the U.S. state of Utah. Together, these formations represent about 150 million years of local sedimentation from the Late Permian to Early Cretaceous. Part of a super-sequence of rock units called the Grand Staircase, the formations exposed in the Zion and Kolob area were deposited in several different environments that range from the warm shallow seas of the Kaibab and Moenkopi formations, streams and lakes of the Chinle, Moenave, and Kayenta formations to the large deserts of the Navajo and Temple Cap formations and dry near shore environments of the Carmel Formation.

Subsequent uplift of the Colorado Plateau slowly raised these formations much higher than where they were deposited. This steepened the stream gradient of the ancestral rivers and other streams on the plateau. The faster-moving streams took advantage of uplift-created joints in the rocks to remove all Cenozoic-aged formations and cut gorges into the plateaus. Zion Canyon was cut by the North Fork of the Virgin River in this way. Lava flows and cinder cones covered parts of the area during the later part of this process. (see more...)

Acrocanthosaurus was a bipedal predator. As the name suggests, it is best known for the high neural spines on many of its vertebrae, which most likely supported a ridge of muscle over the animal's neck, back and hips. Acrocanthosaurus was one of the largest theropods, approaching 12 meters (40 ft) in length, and weighing up to 6.2 tonnes (6.8 short tons). Large theropod footprints discovered in Texas may have been made by Acrocanthosaurus, although there is no direct association with skeletal remains.

Recent discoveries have elucidated many details of its anatomy, allowing for specialized studies focusing on its brain structure and forelimb function. Acrocanthosaurus was the largest theropod in its ecosystem and likely an apex predator which possibly preyed on large sauropods and ornithopods. (see more...)

As a tyrannosaurid, Albertosaurus was a bipedal predator with tiny, two-fingered hands and a massive head with dozens of large, sharp teeth. It may have been at the top of the food chain in its local ecosystem. Although relatively large for a theropod, Albertosaurus was much smaller than its more famous relative Tyrannosaurus, probably weighing less than 2 metric tons.

Since the first discovery in 1884, fossils of more than thirty individuals have been recovered, providing scientists with a more detailed knowledge of Albertosaurus anatomy than is available for most other tyrannosaurids. The discovery of 26 individuals at one site provides evidence of pack behaviour and allows studies of ontogeny and population biology which are impossible with lesser-known dinosaurs. (see more...)

Allosaurus was a large bipedal predator. Its skull was large and equipped with dozens of large, sharp teeth. It averaged 8.5 m (28 ft) in length, though fragmentary remains suggest it could have reached over 12 m (39 ft). It is classified as an allosaurid, a type of carnosaurian theropod dinosaur. The genus has a complicated taxonomy, and includes an uncertain number of valid species, the best known of which is A. fragilis. The bulk of Allosaurus remains have come from North America's Morrison Formation, with material also known from Portugal and possibly Tanzania.

As the most abundant large predator in the Morrison Formation, Allosaurus was at the top of the food chain, probably preying on contemporaneous large herbivorous dinosaurs and perhaps even other predators. Potential prey included ornithopods, stegosaurids, and sauropods. Some paleontologists interpret Allosaurus as having had cooperative social behavior, and hunting in packs, while others believe individuals may have been aggressive toward each other. It may have attacked large prey by ambush, using its upper jaw like a hatchet. (see more...).jpg.webp)

Many presentations still describe Compsognathus as "chicken-sized" dinosaurs because of the small size of the German specimen, which is now believed to be a juvenile. Compsognathus longipes is one of the few dinosaur species for which diet is known with certainty: the remains of small, agile lizards are preserved in the bellies of both specimens. Teeth discovered in Portugal may be further fossil remains of the genus.

Although not recognized as such at the time of its discovery, Compsognathus is the first theropod dinosaur known from a reasonably complete fossil skeleton. Until the 1990s, it was the smallest known non-avialan dinosaur; earlier it was the closest supposed relative of the early bird Archaeopteryx. (see more...)

Daspletosaurus is closely related to the much larger and more recent Tyrannosaurus. Like most known tyrannosaurids, it was a multi-tonne bipedal predator equipped with dozens of large, sharp teeth. Daspletosaurus had the small forelimbs typical of tyrannosaurids, although they were proportionately longer than in other genera.

As an apex predator, Daspletosaurus was at the top of the food chain, probably preying on large dinosaurs like the ceratopsid Centrosaurus and the hadrosaur Hypacrosaurus. In some areas, Daspletosaurus coexisted with another tyrannosaurid, Gorgosaurus, though there is some evidence of niche differentiation between the two. While Daspletosaurus fossils are rarer than other tyrannosaurids, the available specimens allow some analysis of the biology of these animals, including social behavior, diet, and life history. (see more...)

Paleontologist John Ostrom's study of Deinonychus in the late 1960s revolutionized the way scientists thought about dinosaurs, leading to the "dinosaur renaissance" and igniting the debate on whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded or cold blooded. Before this, the popular conception of dinosaurs had been one of plodding, reptilian giants. Ostrom noted the small body, sleek, horizontal posture, ratite-like spine, and especially the enlarged raptorial claws on the feet, which suggested an active, agile predator. The etymology "terrible claw" refers to the unusually large, sickle-shaped talon on the second toe of each hind foot. The fossil YPM 5205 preserves a large, strongly curved ungual. Ostrom looked at crocodile and bird claws and reconstructed the claw for YPM 5205 as over 150 millimetres (5.9 in) long.

In both the Cloverly and Antlers formations, Deinonychus remains have been found closely associated with those of the ornithopod Tenontosaurus. Teeth discovered associated with Tenontosaurus specimens imply they were hunted, or at least scavenged upon, by Deinonychus. (see more...)

This genus of dinosaurs lived in what is now western North America at the end of the Jurassic Period. Diplodocus is one of the more common dinosaur fossils found in the Upper Morrison Formation, a sequence of shallow marine and alluvial sediments deposited about 155 to 148 million years ago, in what is now termed the Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages (Diplodocus itself ranged from about 154 to 150 million years ago). The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs such as Camarasaurus, Barosaurus, Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus.

Diplodocus is among the most easily identifiable dinosaurs, with its classic dinosaur shape, long neck and tail and four sturdy legs. For many years, it was the longest dinosaur known. Its great size may have been a deterrent to the predators Allosaurus and Ceratosaurus: their remains have been found in the same strata, which suggests they coexisted with Diplodocus. (see more...)

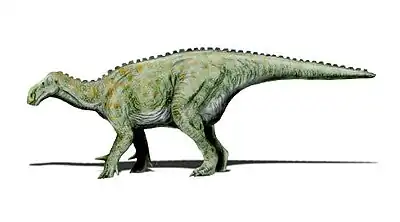

Edmontosaurus has a lengthy and complicated taxonomic history dating to the late 19th century. The type species, E. regalis, was named by Lawrence Lambe in 1917, although several other species that are now classified in Edmontosaurus were named earlier. The best known of these is E. annectens, originally named by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1892.

Edmontosaurus was widely distributed across western North America. The distribution of Edmontosaurus fossils suggests that it preferred coasts and coastal plains. It was an herbivore that could move on both two legs and four. Because it is known from several bone beds, Edmontosaurus is thought to have lived in groups, and may have been migratory as well.

(see more...)

Like most known tyrannosaurids, Gorgosaurus was a bipedal predator weighing more than two metric tons as an adult; dozens of large, sharp teeth lined its jaws, while its two-fingered forelimbs were comparatively small. Gorgosaurus was most closely related to Albertosaurus, and more distantly related to the larger Tyrannosaurus. Some experts consider G. libratus to be a species of Albertosaurus; this would make Gorgosaurus a junior synonym of that genus.

Gorgosaurus lived in a lush floodplain environment along the edge of an inland sea. It was an apex predator (meaning that it was at the top of its food chain), preying upon abundant ceratopsids and hadrosaurs. In some areas, Gorgosaurus coexisted with another tyrannosaurid, Daspletosaurus. Although these animals were roughly the same size, there is some evidence of niche differentiation between the two. Gorgosaurus is the best-represented tyrannosaurid in the fossil record, known from dozens of specimens. These plentiful remains have allowed scientists to investigate its ontogeny, life history and other aspects of its biology. (see more...)

For many years, the classification of Herrerasaurus was unclear because it was known from very fragmentary remains. It was hypothesized to be a basal theropod, a basal sauropodomorph, a basal saurischian, or not a dinosaur at all but another type of archosaur. However, with the discovery of an almost complete skeleton and skull in 1988, Herrerasaurus has been classified as either an early theropod or an early saurischian in at least five recent reviews of theropod evolution, with many researchers treating it at least tentatively as the most primitive member of Theropoda.

It is a member of the Herrerasauridae, a family of similar genera that were among the earliest of the dinosaurian evolutionary radiation. (see more...)

Like other abelisaurids, Majungasaurus was a bipedal predator with a short snout. Although the forelimbs are not completely known, they were very short, while the hindlimbs were longer and very stocky. It can be distinguished from other abelisaurids by its wider skull, the very rough texture and thickened bone on the top of its snout, and the single rounded horn on the roof of its skull, which was originally mistaken for the dome of a pachycephalosaur. It also had more teeth in both upper and lower jaws than most abelisaurids.

Known from several well-preserved skulls and abundant skeletal material, Majungasaurus has recently become one of the best-studied theropod dinosaurs from the Southern Hemisphere. It appears to be most closely related to abelisaurids from India rather than South America or continental Africa, a fact which has important biogeographical implications. Majungasaurus was the apex predator in its ecosystem, mainly preying on sauropods like Rapetosaurus, and is also one of the few dinosaurs for which there is direct evidence of cannibalism. (see more...)

The type species is M. carinatus; seven other species have been named during the past 150 years, but only M. kaalae among these is still considered valid. Prosauropod systematics have undergone numerous revisions during the last several years, and many scientists disagree where exactly Massospondylus lies on the dinosaur evolutionary tree. The family name Massospondylidae was once coined for the genus, but because knowledge of prosauropod relationships is in a state of flux, it is unclear which other dinosaurs—if any—belong in a natural grouping of massospondylids.

Although Massospondylus was long depicted as quadrupedal, a 2007 study found it to be bipedal. It was probably a plant eater (herbivore), although it is speculated that the prosauropods may have been omnivorous. This animal, 4–6 metres (13–20 ft) long, had a long neck and tail, with a small head and slender body. On each of its forefeet, it bore a sharp thumb claw that was used in defense or feeding. Recent studies indicate Massospondylus grew steadily throughout its lifespan, possessed air sacs similar to those of birds, and may have cared for its young. (see more...)Nigersaurus was 9 m (30 ft) long, which is small for a sauropod, and had a short neck. It weighed around four tonnes, comparable to a modern elephant. Its skeleton was filled with air spaces connected to air sacs, but the limbs were robustly built. Its skull was very specialised for feeding, with a wide muzzle filled with more than 500 teeth. The jaws may have borne a keratinous sheath. Unlike other tetrapods, the tooth-bearing bones of its jaws were rotated transversely relative to the rest of the skull, so that all of its teeth were located far to the front.

Nigersaurus was probably a browser, and fed with its head close to the ground. It lived in a riparian habitat, and its diet probably consisted of soft plants, such as ferns, horsetails, and angiosperms. It is one of the most common fossil vertebrates found in the area, and shared its habitat with other dinosaurian megaherbivores, as well as large theropods and crocodylomorphs. (see more...)

Discovered in 1834 by Johann Friedrich Engelhardt and described three years later by Hermann von Meyer, Plateosaurus was the fifth named dinosaur genus that is still considered valid. It is now among the dinosaurs best known to science: over 100 skeletons have been found, some of them nearly complete.

Plateosaurus was a bipedal herbivore with a small skull on a long, mobile neck, sharp but plump plant-crushing teeth, powerful hind limbs, short but muscular arms and grasping hands with large claws on three fingers, possibly used for defence and feeding. Unusually for a dinosaur, Plateosaurus showed strong developmental plasticity: instead of having a fairly uniform adult size, fully grown individuals were between 4.8 and 10 metres (16 and 33 ft) long and weighed between 600 and 4,000 kilograms (1,300 and 8,800 lb). Commonly, the animals lived for at least 12 to 20 years, but the maximum life span is not known. (see more...)

All species of Psittacosaurus were gazelle-sized bipedal herbivores characterized by a high, powerful beak on the upper jaw. At least one species had long, quill-like structures on its tail and lower back, possibly serving a display function. Psittacosaurs were extremely early ceratopsians. Although they developed many novel adaptations, they shared many anatomical features with later ceratopsians such as Protoceratops and Triceratops.

Psittacosaurus is not as familiar to the general public as its distant relative Triceratops but it is one of the most completely known dinosaur genera. Fossils of over 400 individuals have been collected so far, including many complete skeletons. Most different age classes are represented, from hatchling through to adult, which has allowed several detailed studies of Psittacosaurus growth rates and reproductive biology. The abundance of this dinosaur in the fossil record has led to the creation of the Psittacosaurus biochron for Lower Cretaceous sediments of east Asia. (see more...)

Styracosaurus was a relatively large dinosaur, reaching lengths of 5.5 metres (18 ft) and weighing nearly 3 tons. It stood about 1.8 meters (6 ft) tall. Styracosaurus possessed four short legs and a bulky body. Its tail was rather short. The skull had a beak and shearing cheek teeth arranged in continuous dental batteries, suggesting that the animal sliced up plants. Like other ceratopsians, this dinosaur may have been a herd animal, traveling in large groups, as suggested by bonebeds.

Named by Lawrence Lambe in 1913, Styracosaurus is a member of the Centrosaurinae. One species, S. albertensis, is currently assigned to Styracosaurus. Other species assigned to the genus have since been reassigned elsewhere. (see more...)

Although many species have been named, modern paleontologists recognize only one, T. bataar, as valid. Some experts see this species as an Asian representative of the North American genus Tyrannosaurus; this would make the genus Tarbosaurus redundant. Tarbosaurus and Tyrannosaurus, if not synonymous, are considered to be at least closely related genera.

Like most known tyrannosaurids, Tarbosaurus was a large bipedal predator, weighing up to six tonnes and equipped with about sixty large teeth. It had a unique locking mechanism in its lower jaw and the smallest forelimbs relative to body size of all tyrannosaurids, renowned for their disproportionately tiny, two-fingered forelimbs.

Tarbosaurus lived in a humid floodplain criss-crossed by river channels. In this environment, it was an apex predator at the top of the food chain, probably preying on other large dinosaurs like the hadrosaur Saurolophus or the sauropod Nemegtosaurus. Tarbosaurus is very well represented in the fossil record, known from dozens of specimens, including several complete skulls and skeletons. These remains have allowed scientific studies focusing on its phylogeny, skull mechanics, and brain structure. (see more...)This bipedal ornithopod is known from several partial skeletons and skulls that indicate it grew to between 2.5 and 4.0 meters (8.2 to 13.1 ft) in length on average. It had sturdy hind limbs, small wide hands, and a head with an elongate pointed snout. The form of the teeth and jaws suggest a primarily herbivorous animal. This genus of dinosaur is regarded as a specialized basal ornithopod, traditionally described as a hypsilophodont, but more recently recognized as distinct from Hypsilophodon. Several species have been suggested for this genus. Three currently are recognized as valid: the type species T. neglectus, as well as T. garbanii and T. assiniboiensis.

The genus attracted media attention in 2000, when a specimen unearthed in 1993 in South Dakota, United States, was interpreted as including a fossilized heart. There was much discussion over whether the remains were of a heart. Many scientists now doubt the identification of the object and the implications of such an identification. (see more...)

The exact placement of the Triceratops genus within the ceratopsid group has been debated by paleontologists. Two species, T. horridus and T. prorsus, are considered valid. Research published in 2010 suggests that the contemporaneous Torosaurus, a ceratopsid long regarded as a separate genus, represents Triceratops in its mature form, a view not accepted by all researchers. Triceratops has been documented by numerous remains collected since the genus was first described in 1889, including at least one complete individual skeleton. Specimens representing life stages from hatchling to adult have been found.

The function of the frills and three distinctive facial horns has long inspired debate. Traditionally these have been viewed as defensive weapons against predators. More recent theories, noting the presence of blood vessels in the skull bones of ceratopsids, find it more probable that these features were primarily used in identification, courtship and dominance displays, much like the antlers and horns of modern reindeer, mountain goats, or rhinoceros beetles. (see more...)Like other tyrannosaurids, Tyrannosaurus was a bipedal carnivore with a massive skull balanced by a long, heavy tail. Relative to its large and powerful hindlimbs, Tyrannosaurus forelimbs were short and bore two clawed digits. Although other theropods rivaled or exceeded Tyrannosaurus rex in size it is one of the largest known land predators in history. The most complete specimen measures up to 12.3 m (40 ft) in length, up to 4 metres (13 ft) tall at the hips, and up to 6.8 metric tons (7.5 short tons) in weight. Tyrannosaurus rex would have been an apex predator, preying upon hadrosaurs, ceratopsians, and possibly sauropods.

More than 50 specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex have been identified, some of which are nearly complete skeletons. Soft tissue and proteins have been reported in at least one of these specimens. The abundance of fossil material has allowed significant research into many aspects of its biology. Its taxonomy is also controversial: some scientists consider Tarbosaurus bataar from Asia to be a second species of Tyrannosaurus and others maintaining Tarbosaurus as a separate genus. (see more...)

Like other dromaeosaurids like Deinonychus and Achillobator, Velociraptor was a bipedal, feathered carnivore with a long tail and an enlarged sickle-shaped claw on each hindfoot, which is thought to have been used to tackle prey. Velociraptor can be distinguished from other dromaeosaurids by its long and low skull, with an upturned snout.

Velociraptor (commonly shortened to "raptor") is one of the dinosaur genera most familiar to the general public due to its prominent role in the Jurassic Park motion picture series. In the films it was shown with anatomical inaccuracies, including being much larger than it was in reality and without feathers. Some of these inaccuracies, along with the head's larger dome in the movies may suggest that the dinosaurs in the movies were actually modeled on Deinonychus. Velociraptor is also well known to paleontologists, with over a dozen described fossil skeletons, the most of any dromaeosaurid. One particularly famous specimen preserves a Velociraptor locked in combat with a Protoceratops. (see more...)

Like most sauropods, it would have had a long neck and tail but it also carried armor in the form of osteoderms. The blade of the scapula, contrary to most titanosaurs, is triangular. The blade narrows at one end instead of showing an expansion like most other genera. Titanosaurians were a flourishing group of sauropod dinosaurs during Cretaceous times. The Spanish locality from the latest Cretaceous of “Lo Hueco” yielded a relatively well preserved, titanosaurian braincase, which shares a number of unique features with A. atacis from France. However, it appeared to differ from A. atacis in some traits also. The specimen has been provisionally identified as Ampelosaurus sp..

Ampelosaurus lived alongside many other animals. Over 8500 specimens have been found alongside it, including gastropods, bivalves, crocodiles, other sauropods, plants and invertebrates in the Villalba de la Sierra, Gres de Saint-Chinian, Marnes Rouges Inférieures and Gres de Labarre formations. Recent attention has made Ampelosaurus one of the most well-known dinosaurs known from France. (see more...)

Early members of the ceratopsian group, such as Psittacosaurus, were small bipedal animals. Later members, including ceratopsids like Centrosaurus and Triceratops, became very large quadrupeds and developed elaborate facial horns and frills extending over the neck. While these frills might have served to protect the vulnerable neck from predators, they may also have been used for display, thermoregulation, the attachment of large neck and chewing muscles or some combination of the above. Ceratopsians ranged in size from 1 meter (3 ft) and 23 kilograms (50 lb) to over 9 meters (30 ft) and 5,400 kg (12,000 lb).

Triceratops are by far the best-known ceratopsians to the general public. It is traditional for ceratopsian genus names to end in "-ceratops", although this is not always the case. One of the first named genera was Ceratops itself, which lent its name to the group, although it is considered a nomen dubium today as its fossil remains have no distinguishing characteristics that are not also found in other ceratopsians. (see more...)

Cryolophosaurus is known from a skull, a femur and other material, the skull. C. ellioti possessed a distinctive crest on its head that spanned the head from side to side. Based on evidence from related species and studies of bone texture, it is thought that this bizarre crest was used for intra-species recognition. Since its original description, the consensus is that Cryolophosaurus is either a primitive member of the Tetanurae or a close relative of that group.

Cryolophosaurus was first excavated from Antarctica's Early Jurassic, Sinemurian to Pliensbachian aged Hanson Formation, formerly the upper Falla Formation, by paleontologist Dr. William Hammer in 1991. It was the first carnivorous dinosaur to be discovered in Antarctica and the first non-avian dinosaur from the continent to be officially named. The sediments in which its fossils were found have been dated at ~194 to 188 million years ago, representing the Early Jurassic Period. (see more...)

Megalosaurus was, in 1824, the first genus of dinosaur to be validly named, apart from birds. The type species is Megalosaurus bucklandii, named in 1827. In 1842, Megalosaurus was one of three genera on which Richard Owen based his Dinosauria. On Owen's directions a model was made as one of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, which greatly increased the public interest for prehistoric reptiles. Subsequently, over fifty other species would be classified under the genus, originally because dinosaurs were not well known, but even during the 20th century after many dinosaurs had been discovered. Today it is understood these additional species were not directly related to M. bucklandii, which is the only true Megalosaurus species.

Megalosaurus was about seven metres long, weighing roughly 1.5 tonnes. It was bipedal, walking on stout hindlimbs, its horizontal torso balanced by a horizontal tail. Its forelimbs were short, though very robust. Megalosaurus had a rather large head, equipped with long curved teeth. It was generally a robust and heavily muscled animal. (see more...)

Like other pachycephalosaurids, Pachycephalosaurus was a bipedal omnivore with an extremely thick skull roof. It possessed long hindlimbs and small forelimbs. Pachycephalosaurus is the largest known pachycephalosaur.

The thick skull domes of Pachycephalosaurus and related genera gave rise to the hypothesis that pachycephalosaurs used their skulls in intraspecific combat. This hypothesis has been disputed in recent years. (see more...)

Paleontologists Paul Sereno of the University of Chicago, Jeff Wilson of the University of Michigan, and Srivastava worked together as an Indo–American group to study the Narmada River fossils. The fossils represented the partial skeleton of the new species Rajasaurus narmadensis, which means "princely lizard from the Narmada Valley."

The fossilized bones of Rajasaurus have also been found in the upriver region of the Narmada, at Jabalpur, in the state of Madhya Pradesh.(see more...)

Scelidosaurus was about 4 metres (13 ft) long. It was a largely quadrupedal animal, feeding on low scrubby plants, the parts of which were bitten off by the small, elongated, head to be processed in the large gut. Scelidosaurus was lightly armoured, protected by long horizontal rows of keeled oval scutes, that stretched along the neck, back and tail.

One of the oldest known and most "primitive" of the thyreophorans, the exact placement of Scelidosaurus within this group has been the subject of debate for nearly 150 years. This was not helped by the limited additional knowledge about the early evolution of armoured dinosaurs. Today most evidence indicates that Scelidosaurus is a basal member of the Thyreophora, lower placed in the evolutionary tree of life than the Ankylosauridae or the Stegosauridae. (see more...)

Sinoceratops was a medium sized, averagely-built, ground-dwelling, quadrupedal herbivore. It could grow up to an estimated 6 m (19.7 ft) long and 2 metres (6.6 ft) high, and weigh up to 2 tonnes (2.0 long tons; 2.2 short tons). It was the first ceratopsid dinosaur discovered in China, and the only ceratopsid known from Asia. All other centrosaurines, and all chasmosaurines, are known from fossils discovered in North America, except for possibly Turanoceratops. Sinoceratops is also significant because it is one of the largest known centrosaurines, and is much larger than any other known basal members of this group.

Sinoceratops existed in the Xingezhuang Formation during the late Cretaceous. It lived alongside leptoceratopsids, saurolophines, and tyrannosaurines. The most common creature in the formation was Shantungosaurus, to whom most of the material has been assigned to. The animals living alongside Sinoceratops and Shantungosaurus were Zhuchengceratops, Huaxiaosaurus, and Zhuchengtyrannus. (see more...)

Sinosauropteryx was a small theropod with an unusually long tail and short arms. The longest known specimen reaches up to 1.07 m (3.5 ft) in length, with an estimated weight of 0.55 kg (1.2 lb). It was a close relative of the similar but older genus Compsognathus, both genera belonging to the family Compsognathidae. Only one species of Sinosauropteryx has been named: S. prima, meaning "first" in reference to its status as the first feathered non-avialian dinosaur species discovered.

Sinosauropteryx lived in what is now northeastern China during the early Cretaceous period. It was among the first dinosaurs discovered from the Yixian Formation in Liaoning Province, and was a member of Jehol Biota. Well-preserved fossils of this species illustrate many aspects of their biology, such as their diet and reproduction. (see more...)

It was originally mentioned by Franz Nopcsa in 1923 as a subfamily of Acanthopholidae, along with the previously defined Acanthopholinae. The family has gone through many taxonomic revisions since it was defined by Nopcsa in 1902. It is now recognized as a junior synonym of the family Nodosauridae. The subfamily now includes the genera Anoplosaurus, Europelta, Hungarosaurus, and Struthiosaurus, designated as the type genus. Because of the instability of Acanthopholis, the generic namesake of Acanthopholinae, and its current identification as a nomen dubium, Struthiosaurinae, the next named group, was decidedly used over the older one.

Struthiosaurinae appeared at about exactly the same time as the North American subfamily Nodosaurinae. Struthiosaurines range all across the cretaceous, the oldest genus being Europelta at an age of 112 Ma and the youngest being Struthiosaurus at about 85–66 Ma. (see more...)

Although descended from smaller ancestors, tyrannosaurids were almost always the largest predators in their respective ecosystems, putting them at the apex of the food chain. The largest species was Tyrannosaurus rex, one of the largest known land predators, which measured up to 12.3 metres (40 ft) in length and up to 6,500 kilograms (7.2 short tons) in weight. Tyrannosaurids were bipedal carnivores with massive skulls filled with large teeth. Despite their large size, their legs were long and proportioned for fast movement. In contrast, their arms were very small, bearing only two functional digits.

Unlike most other groups of dinosaurs, very complete remains have been discovered for most known tyrannosaurids. This has allowed a variety of research into their biology. Scientific studies have focused on their ontogeny, biomechanics and ecology, among other subjects. Soft tissue, both fossilized and intact, has been reported from one specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex. (see more...)

![]()

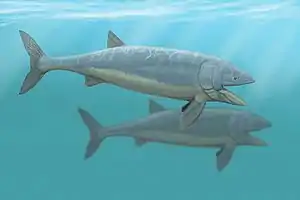

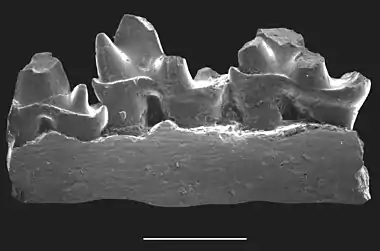

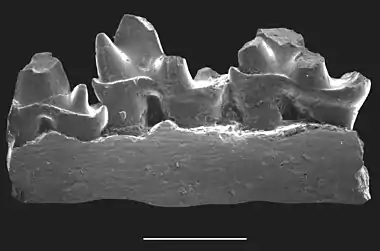

Aetosaur fossil remains are known from Europe, North and South America, parts of Africa and India. Since their armoured plates are often preserved and are abundant in certain localities, aetosaurs serve as important Late Triassic tetrapod index fossils. Many aetosaurs had wide geographic ranges, but their stratigraphic ranges were relatively short. Therefore, the presence of particular aetosaurs can accurately date a site that they are found in.

Aetosaur remains have been found since the early 19th century, although the very first remains that were described were mistaken for fish scales. Aetosaurs were later recognized as crocodile relatives, with early paleontologists considering them to be semiaquatic scavengers. They are now considered to have been entirely terrestrial animals. Some forms have characteristics that may have been adaptations to digging for food. There is also evidence that some if not all aetosaurs made nests. (see more...)

The species was originally described as a pitcher plant with close affinities to extant members of the family Sarraceniaceae. This would make it the earliest known carnivorous plant and the only known fossil record of pitcher plants (with the possible exception of some palynomorphs of uncertain nepenthacean affinity).Archaeamphora is also one of the three oldest known genera of angiosperms (flowering plants). Li (2005) wrote that "the existence of a so highly derived Angiosperm in the Early Cretaceous suggests that Angiosperms should have originated much earlier, maybe back to 280 mya as the molecular clock studies suggested".

Subsequent authors have questioned the identification of Archaeamphora as a pitcher plant. (see more...)

Other formations were also formed but were mostly eroded following uplift from the Laramide orogeny which started around 70 million years ago (mya). This event created the Rocky Mountains far to the east and helped to close the sea that covered the area. A large part of western North America started to stretch itself into the nearby Basin and Range topography around 15 mya. While not part of this region, the greater Bryce area was stretched into the High Plateaus by the same forces.

The formations exposed in the area of the park are part of the Grand Staircase. The oldest members of this supersequence of rock units are exposed in the Grand Canyon, the intermediate ones in Zion National Park, and its youngest parts are laid bare in Bryce Canyon area. A small amount of overlap occurs in and around each park. (see more...)

All damselflies are predatory; both nymphs and adults eat other insects. The nymphs are aquatic, with different species living in a variety of freshwater habitats including acid bogs, ponds, lakes and rivers. The nymphs moult repeatedly, at the last moult climbing out of the water to undergo metamorphosis. The skin splits down the back, they emerge and inflate their wings and abdomen to gain their adult form.

Some species of damselfly have elaborate courtship behaviours. Many species are sexually dimorphic, the males often being more brightly coloured than the females. Like dragonflies, they reproduce using indirect insemination and delayed fertilisation. A mating pair form a shape known as a "heart" or "wheel", the male clasping the female at the back of the head, the female curling her abdomen down to pick up sperm from secondary genitalia at the base of the male's abdomen. The pair often remain together with the male still clasping the female while laying eggs within the tissue of plants in or near water using a robust ovipositor. (see more...)

The known material includes two cervical vertebrae, nine dorsal vertebrae, a few ribs, a fragment of a pubis, and many gastroliths. Of the material, only the vertebrae are diagnostic, with the ribs and pubis being too fragmentary or general to distinguish Dinheirosaurus. This material was first described as in the genus Lourinhasaurus, but differences were noticed and in 1999 Bonaparte and Mateus redescribed the material under the new binomial Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis. Another specimen, ML 418, thought to be Dinheirosaurus, is now known to be from another Portuguese diplodocid. This means that Dinheirosaurus lived alongside many theropods, sauropods, thyreophorans and ornithopods, as well as at least one other diplodocid.

Dinheirosaurus is a diplodocid, a relative of Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Barosaurus, Supersaurus, and Tornieria. Among those, the closest relative to Dinheirosaurus is Supersaurus, and together they form a clade of primitive diplodocids. While they were once considered to be diplodocines they are likely more basal than Apatosaurus. (see more...)

The cervical vertebrae of Apatosaurus are less elongated and more heavily constructed than those of Diplodocus, and the bones of the leg are much stockier despite being longer, implying that Apatosaurus was a more robust animal. The tail was held above the ground during normal locomotion. Apatosaurus had a single claw on each forelimb and three on each hindlimb. Apatosaurus was a generalized browser that likely held its head elevated. To lighten its vertebrae, Apatosaurus had air sacs that made the bones internally full of holes. Like that of other diplodocids, its tail may have been used as a whip to create loud noises.

Apatosaurus is a genus in the family Diplodocidae. It is one of the more basal genera. Brontosaurus has long been considered a junior synonym of Apatosaurus; its only species was reclassified as A. excelsus in 1903. However, the 2015 study concluded that Brontosaurus was a valid genus of sauropod distinct from Apatosaurus. (see more...)