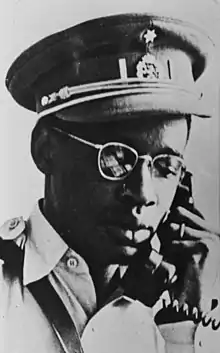

Évariste Kimba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| In office 13 October 1965 – 25 November 1965 | |

| President | Joseph Kasa-Vubu |

| Preceded by | Moise Tshombe |

| Succeeded by | Léonard Mulamba |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs of the State of Katanga | |

| In office 1960 – January 1963 | |

| President | Moise Tshombe |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 16 July 1926 Nsaka, Bukama Territory, Katanga Province, Belgian Congo |

| Died | 2 June 1966 (aged 39) Léopoldville, Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Cause of death | Executed |

| Political party | |

| Spouse | Bernadette |

| Children | 4 |

Évariste Leon Kimba Mutombo (16 July 1926 – 2 June 1966) was a Congolese journalist and politician who served as Foreign Minister of the State of Katanga from 1960 to 1963 and Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 13 October to 25 November 1965. Kimba was born in 1926 in Katanga Province, Belgian Congo. Following the completion of his studies he worked as a journalist and became editor-in-chief of the Essor du Congo. In 1958 he and a group of Katangese concerned about domination of their province by people from the neighbouring Kasaï region founded the Confédération des associations tribales du Katanga (CONAKAT), a regionalist political party. In 1960 the Congo became independent and shortly thereafter Moise Tshombe declared the secession of the State of Katanga. Kimba played an active role in the separatist state's government as its Minister of Foreign Affairs and participated in numerous talks with the central government aimed at political reconciliation. Following the collapse of the secession in early 1963, Kimba had a falling out with Tshombe and took up several ministerial posts in the new province of South Katanga.

Tshombe was later made Prime Minister of the Congo while Kimba joined the Association Générale des Baluba du Katanga (BALUBAKAT) party. On 13 October 1965 President Joseph Kasa-Vubu dismissed Tshombe and appointed Kimba Prime Minister. Kimba formed a government of national unity and spent the following weeks attempting to achieve rapprochement between the Congo and other African states. However, his government failed to obtain a vote of confidence from Parliament, though Kasa-Vubu reappointed Kimba to the premiership in the face of determined opposition from Tshombe's supporters. On 25 November Army Commander-in-Chief Joseph-Désiré Mobutu launched a coup removing both him and Kasa-Vubu from power and assumed control of the presidency. In May 1966 Mobutu's government accused Kimba of plotting with three other former government ministers to launch a coup. He was executed on 2 June for treason.

Early life

Évariste Kimba was born on 16 July 1926 in the village of Nsaka, Bukama Territory, Katanga Province, Belgian Congo.[1][2] Ethnically, he was a member of Luba tribe.[3] His father was a railway worker. He spent much of his youth in Élisabethville, where he attended Roman Catholic schools. After receiving a basic primary and middle education Kimba, like his father, worked on the railroad, but continued his studies, taking night classes at St. Boniface Institute in sociology, law, and political economy.[1][2] He also played on the school's football team.[4]

Kimba took up journalism in 1954 when he began writing for the Essor du Congo in Élisabethville,[5] a conservative, pro-colonial newspaper which covered Katangese affairs. Later that year he became the publication's editor-in-chief, and held the position until 1960.[6] In 1960 he acted as vice president of the Association of the Congolese Press.[7] He married a woman, Bernadette, and had four children with her.[1] In 1958 Kimba attended Expo 58 in Belgium.[5] The following year he traveled abroad, visiting West Germany, Northern Rhodesia, Southern Rhodesia, Senegal, the United States, Canada, France, Switzerland, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece, Ivory Coast, French Cameroon, French Congo, Chad, and French Madagascar.[2]

Political career

Early activities

In February 1957 Kimba and a group of other young Katangese concerned about domination of their province by people from the neighbouring Kasaï region met to discuss the political future of Katanga. In 1958 they founded the Confédération des associations tribales du Katanga (CONAKAT), a regionalist political party.[8]

In the spring of 1960 Walter Ganshof van der Meersch was appointed the Belgian Minister of African Affairs and sent to the Congo to oversee its transition to independence.[9] Ganshof made Kimba his assistant chief of staff.[7] On 12 June the Provincial Assembly of Katanga elected him to the Senate on a non-customary CONAKAT list.[10][7] On 16 June the Katangese provincial government was formed and Kimba was appointed Minister of Commerce and Industry.[7] The Republic of the Congo became independent on 30 June.[11]

Minister of Foreign Affairs of the State of Katanga

On 11 July 1960 Katangese Provincial President Moise Tshombe declared the secession of the "State of Katanga".[12] This was opposed by the regional Luba-dominated party, the Association Générale des Baluba du Katanga (BALUBAKAT), but Kimba allied himself with Tshombe[3] and maintained that the Katangese Baluba belonged to the Katangese "nation".[13] Tshombe made Kimba Katanga's Minister of Foreign Affairs.[14] Dominique Diur also applied for the position, but Kimba was chosen because Godefroid Munongo opposed Diur's nomination.[15] In December, Kimba accompanied Tshombe to a conference with leaders of the national Congolese government in Brazzaville to discuss political reconciliation. The talks dissolved without any tangible progress being achieved.[16] Though the role of the full Katangese government diminished over time under Tshombe's leadership, Kimba still actively met with Tshombe and held press conferences.[17]

In April 1961 Kimba and Tshombe went to Coquilhatville for further talks with the central government on political reconciliation and revising the Congolese constitution. Unhappy with the conference, Tshombe attempted to leave on 26 April, but he and Kimba were arrested and imprisoned for six weeks.[18] They were released on 22 June and allowed to return to Katanga.[19] In exchange for their liberation, the two men signed an agreement with the Congolese government declaring that representatives from Katangese constituencies would appear in the next session of Parliament. They later repudiated the agreement.[20] In March and May 1962 the Katangese government held further talks with the central government in Léopoldville, the Congolese capital.[21] While Tshombe was gone, Kimba went on a tour of Luba areas in Katanga to rally their favour in support of the secession.[22] On 18 May the last round of the Léopoldville negotiations was due to take place, but Tshombe, stalling for time, stayed in Katanga and sent Kimba in his place.[21] Under military pressure from the United Nations Operation in the Congo, Tshombe declared the end of the Katangese secession in January 1963;[23] on 19 January he received UN officials at his residence and, in the presence of Kimba and some of his other ministers, declared that he would accept the UN's terms for Katanga's reintegration into the Congo.[24]

Break from Tshombe

In the aftermath of the secession, Kimba had a falling out with Tshombe; Kimba preferred reconciliation with the central government, but Tshombe did not wish it at the time.[1] Tshombe went to Paris,[25] while in February 1963 Kimba became Minister of Education of the new province of South Katanga. From April until August he served as the province's Minister of Economic Affairs and Minister of Information.[7] In June he went to Léopoldville, to reach an understanding with the central government.[25] In September he attended a conference of moderate political parties in Luluabourg as an observer. On 18 September Kimba went to Europe for "health reasons". He returned to the Congo in January 1964. On 13 December he was elected president of the central committee of the Entente Muluba, an Élisabethville-based organisation.[7]

That year Tshombe was welcomed back into the country and made Prime Minister at the helm of a transitional government tasked with suppressing a leftist insurrection in the eastern Congo. After this was largely accomplished, general elections took place in 1965 and Tshombe's new coalition organisation, the Convention Nationale Congolaise (CONACO) won a majority of the seats in Parliament.[26] Kimba also contested in the election for a seat in the Chamber of Deputies, and won on a BALUBAKAT list. Afterwards he took a brief trip to Paris.[7] Shortly before Parliament was due to reopen, the strength of CONACO faltered, and an anti-Tshombe coalition, the Front Democratique Congolais (FDC), was formed.[27] Kimba joined it in October.[7]

Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

In the months following the elections, the political rivalry between Tshombe and the President of the Congo, Joseph Kasa-Vubu, grew increasingly tense. At the first session of the new Parliament on 13 October 1965, Kasa-Vubu unexpectedly announced that Tshombe's transitional government had fulfilled its purpose. He named Kimba the new Prime Minister and tasked him with forming a government of national unity.[28][27] Kimba had little personal following or national reputation and thus was considered inoffensive to members of Parliament and of little threat to Kasa-Vubu's ambitions. Kasa-Vubu also hoped that by appointing another Katangese to the post, he would avoid aggravating persisting secessionist sentiment in Katanga.[3] Kimba's government was installed on 18 October,[29] representing 16 of the 39 political parties with members in Parliament.[30]

Kimba's government was more nationalistic than Tshombe's administration[31] and aimed to curb Western influence in Congolese affairs;[32] it was markedly less amicable towards Belgian interests.[31] The new cabinet sought to improve the Congo's relations with active countries in the Organisation of African Unity including Ethiopia and Ghana, and to distance itself from the members of the African and Malagasy Common Organisation.[32] The government opened negotiations with Congo-Brazzaville, and on 5 November Kimba announced that in its first step towards rehabilitating the Congo's ties with African states his government was renewing ferry traffic across the Congo river between Brazzaville and Léopoldville, which had been suspended for two years.[33] The following day he formally reestablished diplomatic relations with Congo-Brazzaville.[34][35][lower-alpha 1] He also reopened the Congo-Uganda border, which had been closed since February.[34] Kimba revised the composition of his government on 8 November.[36]

Tshombe's removal from power angered his supporters, and in the following weeks they competed with anti-Tshombe partisans for dominance in Parliament. On 14 November the Kimba Government was presented to the legislature for a formal vote of confidence. It was defeated, 72 to 76 in the Chamber of Deputies and 49 to 58 in the Senate.[37] The next day Kasa-Vubu renominated Kimba as Prime Minister, resulting in a political deadlock.[30] On 25 November, Army Commander-in-Chief Joseph-Désiré Mobutu, who had previously supported Kimba, launched a coup removing both him and Kasa-Vubu from power and assumed control of the presidency.[38] Colonel Léonard Mulamba was appointed to replace Kimba.[39]

Arrest and execution

In May 1966 Kimba and former government ministers Jérôme Anany, Emmanuel Bamba, and Alexandre Mahamba were arrested by Mobutu's security forces while attending a meeting with military officials. They were taken to a military camp and tortured. Mobutu's regime accused them of plotting to assassinate Mobutu and Prime Minister Mulamba and overthrow the government. On 30 May the four men were tried before a military tribunal. The trial lasted an hour and a half and the accused were allowed no legal counsel.[40] They pleaded innocence, claiming that they had been working at the behest of officers in the army. After deliberating for seven minutes, the three military judges found the four men guilty of treason and sentenced them to death.[41] This was in violation of standing Congolese law, which did not consider plotting a coup to be a capital crime.[40] On 2 June 1966, Kimba and the other men were publicly hanged in Léopoldville before a large crowd.[42] This was the first public execution in the Congo since the 1930s. Kimba was the first of the four to be executed; it took him 20 minutes to die after being dropped.[43] His family never received his body.[40]

Kimba was the second former Prime Minister of the Congo to be killed after Patrice Lumumba.[44] Some time after Kimba's death, the Avenue des Chutes in Lubumbashi (formerly Élisabethville) was officially renamed in his honour, though the street is still usually referred to by its original name.[45] In 2011 a congress of the "Luba People" declared that Kimba was among "our valiant martyrs".[46]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Congo's New Premier: Evariste Leon Kimba" (PDF). The New York Times. 17 October 1965. p. 14. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 Gerard-Libois & Verhaegen 2015, p. 353.

- 1 2 3 "Congo: Kasavubu Acts". Link. Vol. 8. 1965. p. 28.

- ↑ "Aide Reports Katanga Is Organizing Services". The New York Times. 15 October 1960. p. 2.

- 1 2 "ÉVARISTE KIMBA un autre Katangais". Le Monde (in French). 15 October 1965. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ↑ McDonald 1962, p. 412.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Gerard-Libois & Verhaegen 2015, p. 354.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, pp. 236, 503.

- ↑ Kanza 1994, p. 96.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, pp. 325–326.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 328.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, pp. 330, 333.

- ↑ Kennes & Larmer 2016, p. 53.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 331.

- ↑ Biographie historique du Congo. University of Lubumbashi. 2000. pp. 9–11.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 364.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, pp. 377, 443.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 382.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 385.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 401.

- 1 2 Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 462.

- ↑ Wilson, Andrew (4 May 1962). "Rising Hope in the Congo". Daily Colonist. p. 4.

- ↑ O'Ballance 1999, p. 63.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 491.

- 1 2 Lukas, J. Anthony (22 June 1963). "Katangese Asks for Congo Accord". The New York Times. p. 6.

- ↑ Young & Turner 1985, pp. 48–49.

- 1 2 "Tshombe Dismissed, Kimba New Premier". Africa Diary. Vol. 5, no. 45. 1965.

- ↑ Young & Turner 1985, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ "Kasavubu Installs New Congo Regime". The New York Times. 19 October 1965. p. 12.

- 1 2 Young & Turner 1985, p. 51.

- 1 2 Gibbs 1991, p. 162.

- 1 2 "Congo's "National Unity" Government: Mr. Tshombe a Likely Candidate for the Presidency". African World. December 1965. p. 15.

- ↑ "Leopoldville Reopening Ferry to Brazzaville". The New York Times. 6 November 1965. p. 2.

- 1 2 O'Ballance 1999, p. 90.

- 1 2 "2 Congos Resumes Ties After 2 Years". The New York Times. United Press International. 7 November 1965. p. 55.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 541.

- ↑ Young & Turner 1985, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Young & Turner 1985, p. 52.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 542.

- 1 2 3 Ikambana 2006, p. 56.

- ↑ "Death Sentence Given 4 Congo Ex-Officials: Former Premier, 3 Others Convicted and Doomed for Treason in 90-Minute Trial". The Los Angeles Times. United Press International. 1 June 1966. p. 19.

- ↑ "100,000 in Congo See Hanging of Ex-Premier and 3 Others" (PDF). The New York Times. Associated Press. 2 June 1966. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ↑ Williams 2021, p. 518.

- ↑ Kirk, Russel (9 June 1966). "A Revolution's Victims". The Los Angeles Times. p. B5.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, p. 664.

- ↑ Omasombo Tshonda 2018, pp. 603, 605.

Bibliography

- Gerard-Libois, Jules; Verhaegen, Benoit (2015). Congo 1965: Political Documents of a Developing Nation (in French) (reprint ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400875436.

- Gibbs, David N. (1991). The Political Economy of Third World Intervention: Mines, Money, and U.S. Policy in the Congo Crisis. American Politics and Political Economy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226290713.

- Ikambana, Jean-Louise Peta (2006). Mobutu's Totalitarian Political System: An Afrocentric Analysis. Routledge. ISBN 9781135861513.

- Kanza, Thomas R. (1994). The Rise and Fall of Patrice Lumumba: Conflict in the Congo (expanded ed.). Rochester, Vermont: Schenkman Books, Inc. ISBN 0-87073-901-8.

- Kennes, Erik; Larmer, Miles (2016). The Katangese Gendarmes and War in Central Africa: Fighting Their Way Home. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02130-4.

- McDonald, Gordon, ed. (1962). Area Handbook for the Republic of the Congo (Leopoldville). Washington D.C.: American University Foreign Areas Studies Division. OCLC 1347356.

- O'Ballance, Edgar (1999). The Congo-Zaire Experience, 1960–98. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-28648-1.

- Omasombo Tshonda, Jean, ed. (2018). Haut-Katanga : Lorsque richesses économiques et pouvoirs politiques forcent une identité régionale (PDF). Provinces (in French). Vol. 1. Tervuren: Musée royal de l’Afrique centrale. ISBN 978-9-4926-6907-0.

- Williams, Susan (2021). White Malice : The CIA and the Covert Recolonization of Africa. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-5417-6829-1.

- Young, Crawford; Turner, Thomas Edwin (1985). The Rise and Decline of the Zairian State. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299101138.