| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Registered | 9,977,452 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 7,542,936 (75.6%) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Results by department | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

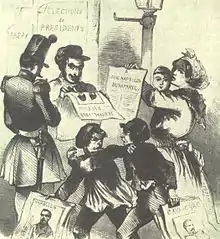

Presidential elections were held for the first time in France on 10 and 11 December 1848, electing the first and only president of the Second Republic. The election was held on 10 December 1848 and led to the victory of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte with 74% of the popular vote. This was the only direct presidential election until the 1965 French presidential election. The six candidates in the election, in order of most votes received, are Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte of the Bonapartists, Louis Eugène Cavaignac of the moderate Republicans, Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin of the Montagnards, François-Vincent Raspail of the Socialists, Alphonse de Lamartine of the Liberals, and Nicolas Changarnier of the Monarchists.

Background

The Constitution

Following the February 1848 revolution, the French replaced the July Monarchy of Louis-Philippe with a constitutional republic. The revolution came as a surprise to most.[1] The new Second Republic was led by a provisional government and then an executive commission, which held democratic elections for a National Constituent Assembly. The National Constituent Assembly was tasked with drafting a new Constitution for the Second Republic, including the definition of a new head of state to replace the overthrown monarchy.

Constitutional debates took place during the period known as the June Days Uprising. The Second Republic had initiated National Workshops to alleviate urban unemployment. These workshops were paid for by high taxes but were ultimately unable to financially maintain them. The closing of the workshops sparked the June Days Uprising. The countryside was broadly opposed to the uprising. Karl Marx argues peasants, specifically conservative farmers, desired government protection, meaning a strong autocratic executive.[2] Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte was the only prominent political figure not to be associated with the June uprising in any manner due to him being in England at the time.[3]

The presidency was defined by the terms of the constitution. Rather than the model of the executive committee given by the First Republic, the constitutional committee preferred to entrust executive power in a single individual. The office was given extensive powers to propose legislation, appoint ministers and high-ranking officials, engage in diplomacy, and command the military, though all decisions were subject to approval by the ministers.

General Political Climate

Alexis de Tocqueville commented that “the collapse of commerce, ubiquitous hostility, and fear of socialism increasingly aroused hatred of the Republic” and that “everyone wanted to get rid of the constitution.”[4] The April elections already signaled hostility to the Republic: only about a third of seats went to pre-revolution republicans. After the June uprising, politics became divided between a frightened conservative majority no longer interested in compromise and a bitter republican minority.[5]

Napoleon I remained widely popular. There had been a cult dedicated to him ever since the empire fell, which was especially strong in the countryside, and the countryside was the majority of the population. Napoleon I became associated with national pride, a legend that the July Monarchy added to by trying to lean on it for credibility. Some republicans even saw Napoleon I as having furthered the Revolution and does not see Bonapartism as opposed to their cause. Louis Napoleon had attempted to seize power in 1836 and 1840, which even though were total failures, had established him as the “Bonapartist pretender.” [6]

Workers and socialists saw the National Workshops as the first step to restructuring society and the abolition of capitalism, and thus attached to it a great deal of symbolic importance. To everyone else, the June uprising made a strong executive seem essential.[6] Notables like Alexis de Tocqueville and Karl Marx saw the June Uprising as an instance of class warfare.[4] The left was concerned almost exclusively with urban poverty, and neglected the conditions of the countryside.

The French peasantry faced numerous economic hardships during the Second Republic. Most hated of all was the 45 centime (a centime equivalent to 1/100 of a Franc) tax to pay for the National Workshops. Mortgage rates were also sky-high. The lenders, perhaps not a coincidence, happened to often be government officials. Harvests had begun improving, which drove prices down, and smaller farmers were especially impacted.[7]

Strengths and Weaknesses of Candidates

Two monarchist factions, Orleanists and Legitimists, could not agree on a potential candidate and thus both ended up supporting Louis Napoleon.[5] The conservative Party of Order, a coalition of monarchists, stayed neutral, which benefitted Louis Napoleon as it does not split the conservative vote with a third-party candidate. The only other conservative candidate in the race, Changarnier, never gained much traction. The Party of Order would go on to oppose Bonaparte's presidency. The urban working class were not a coherent voting bloc and numerous candidates courted their votes.

Bonaparte's Extinction of Pauperism/Poverty (depending on translation) was not unique, but did establish Louis Napoleon as a friend of the worker. The main difference he presented from utopian socialism was the militaristic government intervention to carry out the social plans and advocacy for agricultural colonies.[5] Bonapartism also appealed to the left in its egalitarianism and resentment of “the rich.”[5][6] Louis Napoleon was not seen as an enemy by rank-and-file republicans due to him attaching the republican universal suffrage and active foreign policy to his platform. His proclaimed social aims include meritocracy, cheap credit, less taxation, property for all men, and public works especially communication. Workers did not as a whole identify Bonaparte as in the pockets of Big Business, and his advocacy for public works meant employment and lowered cost of transportation. Newly enfranchised peasants saw the centralized state Louis Napoleon advocated for as their liberation from noble rulers.[8]

Cavaignac remained widely resented by Parisian workers as the Butcher of June in his role suppressing the June Days Uprising as the Minister of War. He and the Second Republic was also widely resented for imposing high taxes. Rumors had begun circulating before the election that Cavaignac was planning a coup.[3]

Cavaignac enjoyed the support of Protestants as well as liberal Catholics. As Louis Napoleon carried the Napoleonic legacy, Cavaignac also overperformed in areas where Napoleon I was not as popular, such as port cities that suffered British blockade during the Napoleonic Wars.[3][6]

Electoral system

The Constitutional Committee decided that the presidential executive should be chosen by universal male suffrage in late May. The procedure for presidential election was ratified by referendum on 6 October and included in the Constitution, which was adopted on 12 November. Most prominent political figures in France supported election by popular vote. Cavaignac repeatedly opposed legal measures that could have hindered Louis Napoleon, offering various justifications that it's better for the Republic. Alexis de Tocqueville argued “the executive would be too weak if chosen by the Assembly.”[3] By the time the Constitution came up for debate in October, opposition to general election for president consisted of monarchists and republicans trying to stop Louis Napoleon.[3] The election was scheduled for 10 December.

The constitution only included provision for one round, and in the absence of a majority for any candidate, the National Assembly would have decided the victor.[9] Louis-Eugène Cavaignac seemed certain to win if the election reached the National Assembly. Louis Napoleon was widely expected to win but it was unclear by what percentage he would win. There was a real chance that he would lack an outright majority and thus be defeated in the Assembly.[3]

Results

Bonaparte had no long political career behind him and was able to depict himself as "all things to some men". The Monarchist right (supporters of either the Legitimist or Orléanist royal households) and much of the upper class supported him as the "least worst" candidate, as a man who would restore order, end the instability in France which had continued since the overthrow of the monarchy during the February Revolution earlier that year, and prevent a proto-communist revolution (in the vein of Friedrich Engels). A good proportion of the industrial working class, on the other hand, were won over by Louis-Napoleon's vague indications of progressive economic views. His overwhelming victory was above all due to the support of the non-politicized rural masses, to whom the name of Bonaparte meant something, as opposed to the other, little-known contenders.[10]

Cavaignac conceded before results were even fully in.[3] Bonaparte received a plurality or majority in all departments except the Var, Bouches-du-Rhône, Morbihan, and Finistère, all four of which were won by Cavaignac. Thus did Bonaparte become the second president in Europe (after Jonas Furrer of Switzerland) and the first French president to be elected by a popular vote.

The presidential election in December had abstention rate of 25%, up from 16% in initial legislative elections in April.[11]

| Candidate | Party | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte | Bonapartists | 5,434,226 | 74.33 | |

| Louis-Eugène Cavaignac | Moderate Republicans | 1,448,107 | 19.81 | |

| Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin | The Mountain | 370,119 | 5.06 | |

| François-Vincent Raspail | Socialist | 36,920 | 0.50 | |

| Alphonse de Lamartine | Liberal | 17,210 | 0.24 | |

| Nicolas Changarnier | Monarchist | 4,790 | 0.07 | |

| Total | 7,311,372 | 100.00 | ||

References

- ↑ Marx, Karl (1913). The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Translated by De Leon, Daniel (3rd ed.). Charles H. Kerr & Company. pp. 13–75.

- ↑ Marx, Karl (1913). The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Translated by De Leon, Daniel (3rd ed.). Charles H. Kerr & Company. pp. 145–147.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 De Luna, Frederick A. (1969). The French Republic Under Cavaignac, 1848. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 365–395.

- 1 2 Tocqueville, Alexis de (2016). Zunz, Olivier (ed.). Recollections : the French Revolution of 1848 and Its Aftermath. Translated by Goldhammer, Arthur. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. pp. 94–135.

- 1 2 3 4 McMillan, James F. (1991). Napoleon III. London: Longman. pp. 8–33.

- 1 2 3 4 Price, Roger (1997). Napoleon III and the Second Empire. London: Routledge. pp. 1–15.

- ↑ Fasel, George (1974). "The Wrong Revolution: French Republicanism in 1848". French Historical Studies. 8 (4): 654–77. doi:10.2307/285857. JSTOR 285857 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Zeldin, Theodore (1973). France, 1848-1945. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 508–554.

- ↑ Alexis de Tocqueville, Souvenirs (chap. XI), Robert Laffont, Paris, 1986, pp. 831–834.

- ↑ "France: Election of President".

- ↑ Zeldin, Theodore (1973). France, 1848-1945. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 388–389.