| 1906 Porto Alegre general strike | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 3 - 21 October 1906 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Long working hours, low wages | ||

| Goals | The eight-hour day, wage increases | ||

| Resulted in | Recognition of the nine-hour workday

| ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

The 1906 Porto Alegre general strike, also known as the 21-day strike, was the first general strike in the history of Rio Grande do Sul. Between 3 and 21 October, about five thousand workers abandoned their work, demanding the reduction of the workday to eight hours. The movement was initiated by anarchists, who had started a strike on August 26 at Jacob Aloys Friedrichs marmoraria demanding the eight-hour day. Soon after the strike statement, they founded the Marbles Union and called the other workers in Porto Alegre to join the movement. Throughout September, the city's working class remained solidarity to paralyze marble production, and on October 3, several sectors decided to declare themselves on strike.

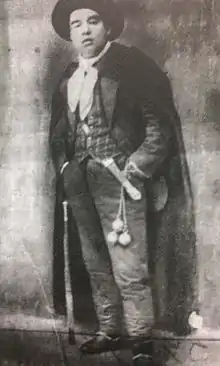

Faced with the paralysis of several sectors - including metallurgical, stevedores, masons, tram workers and textiles, the local entrepreneurship met under the leadership of Alberto Bins to establish an agreement that granted the workers a nine hour workday, which initially was not accepted by the strikers. During the strike, the socialists Francisco Xavier da Costa and Carlos Cavaco emerged as leaders of the movement, bringing the anarchists in their direction and driving the creation of the Workers' Federation of Rio Grande do Sul (FORGS), which would become the most important organization of the Gaúcha working class during the first Republic. The bosses remained uncompromising and the strike began to empty themselves from October 17, when several workers, pressured by the economic difficulties arising from so much time paralyzed, began to return to work, accepting the nine-hour workday. On the 21st, the local press declared the movement to have ended. Despite the original demand was not met, the reduction of the working day was seen as a partial achievement, and the strike helped to strengthen class consciousness and the organization of Porto Alegre's workers.

Background

According to historian Joan Bak, the 1906 general strike in Porto Alegre was initiated in a context in which at least three elements stand out: the introduction of new modalities of production, which disrupted the familiar habits of artisan labor; the growing introduction of the female workforce in the work environment; and the transformation of hermetic ethnic communities into more heterogeneous communities, which were to be recognized as a working class.[1]

Until the beginning of the twentieth century, in most Porto Alegre companies, a typical organization of manufacturing workshops, with a relatively small number of employees and a hierarchy of functions based on talent and in the time of professional learning. This working environment brought possibilities of hierarchical ascension to employees, as well as allowed a greater proximity between them and their bosses, favoring paternalist social relations.[2] The workers of the first workshops and industries were almost always qualified male artisans, in general European immigrants or descendants.[3] Entrepreneurs generally hired only fellow countrymen in an attempt to accentuate ethnic solidarity and camouflage class differences. Linguistic barriers eventually isolated the immigrant workers from those that spoke Portuguese, reinforcing cultural ties between bosses and employees.[4] Black people and mestiços, even if they formed an important part of the population of the city, were relegated to unqualified and poorly paid work, while many entrepreneurs hired only workers of European origin.[3]

In the early 1900s, an expansion of industry and the most traditional social relations between boss and employee have begun to modify with the emergence of large factories. As a result of this process, some craftsmen blamed the machines for having taken them from their former work and complained that they were working more and earning less. Establishments which employed more than 50 workers became more common, concentrated especially in metallurgy, clothing production, furniture and food. According to Bak, "these establishments have become a first battlefield of conflicts for changes in social production relations",[5] including the first strikes, until then always circumscribed to only single establishments. With the appearance and expansion of new factories, the female workforce also became increasingly employed. At the socks and corset factory of the Fabril Porto-Alegrense company, one of the largest and most mechanized of the city, three-quarters of the workforce was composed of women, who worked for low wages and in unhealthy conditions.[6]

As a consequence of this initial process of industrialization, Porto Alegre went through rapid urban growth. The population of the city, from 52,000 inhabitants in 1890, had doubled in 1910, and new urban districts have also emerged in that period. The expansion of the city was mainly to the north and east. The Fourth District Zone - current neighborhoods of São João and Navegantes - emerged as the first industrial region of the city, where there was a working class presence.[5]

As a result of these rapid transformations, dense and hermetic ethnic communities began to transform into more heterogeneous communities with mixture of ethnic and class identities.[7] While at first the organizations of the working class were marked by ethnicity, as early as 1896, the International Working League congregated Portuguese, German and Italian speakers. At the beginning of the twentieth century, anarchist militants began to organize unions by occupation, although at first, some offices were identified with certain ethnicities - the Italians predominated among shoemakers; the Germans, in turn, among the metallurgists, Hatters and Joiners.[8]

The strike

Marbles strike

.jpeg.webp)

On August 26, 1906, three marble workers of Jacob Aloys Friedrichs - Henrique Faccini, Carlos Jansson and Arthur do Vale Quaresma - gave him a letter in which they demanded the eight-hour workday.[9] The demand of the eight-hour workday was not a novelty in the labor movement: gaucho socialists had already demanded it since 1897, when the policy appeared in the program of the Rio Grande do Sul Socialist Party; also in 1906, between April 15 and 22, the First Brazilian Workers' Congress was held in the Rio de Janeiro, which placed the fight for eight hours on the agenda.[10] Militants of the labor movement, especially anarchists, considered that the eight-hour journey would help reduce unemployment and allow workers to organize and educate themselves in their free time, making their class consciousness grow.[11] Although Rio Grande do Sul had not sent representatives to the Workers' Congress, the Anarchists of Porto Alegre took note of the proposals approved at the meeting,[10] and inspired by Congress, decided to start a movement for eight hours.[12] Henrique Faccini and André Arjonas, signatories of the letter delivered to Friedrichs, were anarchist militants.[13]

The marble workers, as well as other craftsmen, possessed their own tools and were qualified, which made them difficult to replace. However, they worked 11 hour days. In the letter delivered to Friedrichs, the marble workers were identified as a working class and justified their demands arguing that this measure would give them "some time for moral and intellectual development".[14] The employees of Friedrichs believed that he was the most suitable for introducing the eight-hour workday in the city [15] and expected a favorable response from their boss, otherwise they were willing to take a "different resolution".[13]

Despite the respectful and cordial tone of the letter, which did not display hostility or revolutionary ardor, considering Friedrichs as an "honest man" and "laborious and acquiescent with everything that is fair and that has always treated them well".[14] The threat of a "different resolution" irritated the boss. The next morning, August 27, Friedrichs found only one employee in the marmoraria; all others, even apprentices, were absent. Through an informant who declared himself neutral, he knew that his employees would only return to work after they know the answer to the request presented the day before.[13] Then there was a deadlock: Friedrichs said that while his employees "did not go back to work and wait calmly" their response, "could wait indefinitely." He established their return to work as a condition of his response to employees and stated that the issue "no longer revolved around the eight-hour workday," with which Friedrichs had already "conformed intimately," but for his "authority of Master and employer".[2]

The strikers stayed firm for a week. At the end of this period, Friedrichs reported that he was to reduce the working day to nine hours and imposed an ultimatum: if workers rejected this proposal, they should remove their instruments from work until seventeen hours the next day. The marble workers named a commission to reach an agreement with Friedrichs, who remained uncompromising. The Commission, in turn, stated to the boss that workers would go on strike while their demands were not met.[16] On the next day, a group of strikers tried to withdraw their tools from the workshop, but the boss refused to deliver them and asked for police protection. The workers convinced the police that they were only claiming what already belonged to them and, when the police gave up, they entered quietly in the establishment, they collected their belongings and left.[17]

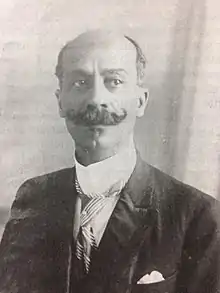

On September 10, the socialist Francisco Xavier da Costa offered to mediate the conflict, writing Friedrichs and arguing that it would be "absolutely impossible to reach an agreement between you and your former workers, provided that you do not have the benevolence of meeting what they have requested, that is - the reduction of labor to eight hours daily."[18] Despite being Brazilian and mestiço, Xavier da Costa had ties with the German-speaking community [19] and had already acted as mediator between bosses and employees in the strike of the wiring and tissues company in the previous year. For these reasons - and also in an attempt to strengthen his leadership in the local labor movement and block the advancement of the anarchists - he tried to seek a negotiated exit to the conflict.[20]

During the month of September, almost all the workers of the city remained in solidarity with the strikers. On September 25, nine marble workers, including Henry Faccini, embarked down to Rio de Janeiro, where they would be employed in the eight-hour regime. Representatives from various associations of workers attended the port in a demonstration of support for the marble workers.[21]

Generalization of strike

Soon after the strike statement, the marble workers founded the Marbles Union and called the workers of the city to join the fight, through a manifesto in which they asked for the adhesion of the local operations to the idea of the eight hour day.[22] On September 9, the masons and hatters responded to the call by organizing their own unions. Textile workers and tailors also began to organize and the union of the metallurgists was encouraged to enter into action.[23] Xavier da Costa and Carlos Cavaco, the main socialist leaders from Porto Alegre, began to organize workers' rallies inciting the workers to fight for the eight-hour day. The first of these rallies occurred on September 11. On the 20th of the same month, when the city celebrated the Farroupilha Revolution, Xavier da Costa, Carlos Cavaco and the German Socialist José Zeller-Rethaler spoke to workers.[24] On the 23rd, a Sunday, Xavier da Costa and Carlos Cavaco promoted a new rally in Customs Square in the center of Porto Alegre. Xavier da Costa spoke on the antagonism between the working class and the bourgeoisie; Cavaco attacked "the stupid bourgeoisie and its extravagances" while the workers faced misery. He also talked about the workers' movement in Germany and France and emphasized the need for local initiatives to unite in a federation. In addition, he advised workers to physically resist the demands of the "potented exploiters, if necessary, raising barricades in the middle of the streets and demanding their ideals with an olive branch in one hand and the other, if necessary, a dynamite bomb."[25] Along the strike, Cavaco was the only leader that publicly advised the use of violence against bosses.[26]

With the arrival the month of October, workers in other industrial sectors joined the marble workers.[27] On day 3, in the morning, the metallurgists gathered at the Railroad Cafe, on rua Voluntários da Pátria, where they decided to join the strike and demand, beyond the decrease of working hours, a salary increase. On the same day, the workers of the Phoenix foundry, the foundry and shipyard of Alberto Bins, the Arbós & Salvador furniture factories, the shipyards of José Becker and the foundry of Jacques Max adhered to the strike, according to Jornal do Commercio. The next day, the workers of the Silva Só & Son Iron Foundry and the pairs that worked in the works of the American bookstore also joined the movement. At the Kappel & Arnt Furniture Factory the workers did not get to strike, since the owners of that establishment advanced in the negotiations and, in accordance with those of Arbós & Salvador factories, reduced the workday to an average of nine hours daily, which was accepted by both factories workers. The workers of Arbós & Salvador, which the day before had adhered to the strike, returned to work.[28]

Xavier da Costa and Carlos Cavaco, in an attempt to direct the movement, divided into the functions of advertising and organization of the strike. On October 3, while Xavier da Costa participated in the Metallurgical Meeting at the Railroad Café, Cavaco made an address at the Union headquarters in the Morro São Pedro to Masons and Woodworkers, counseling the greatest calm and whole order in the peaceful resistance they should offer to bosses.[29] According to historian Benito Schmidt, the change in the tone of the speeches - especially by Carlos Cavaco - must be attributed to the wish of the socialist leaders in attracting the sympathies of other social groups to the cause of workers.[30]

.jpg.webp)

On the afternoon of the 5th, industrialists, contractors and merchants held a meeting to find a means of solving the impasse with the workers. At that meeting, Alberto Bins emerged as a leader, then becoming the most influential articulator of the employer group. Most entrepreneurs agreed to establish a nine-hour workday. Faced with this, Bins proposed that this workday be adopted unanimously by all bosses.[31] Entrepreneurs established an agreement establishing that the nine-hour workday proposal would not be modified; whereas the workers who took part in the strike could not be accepted at another establishment within the period of thirty days, provided that they did not exhibit any justification of their former bosses; and the appointment of a commission to deal with the police chief Pedro Afonso Mibielli in order to ensure that workers willing to abandon the movement could return to work. Bins also proposed the creation of a society of industrialists, whose function would be to "deliberate every time their interests were at stake."[32] The patron position became clear in the declarations of Bins to the Correio do Povo of the day 7: tending him, nor "in old Europe, where the socialist party, after the Catholic is the strongest, has not yet been able to impose his will", and that the adoption of the eight-hour workday in the Gaucho capital "would constitute this fact a victory of such a nature, which would put the bosses in the position of clerks of his workers, who, tomorrow, would judge in the right to make new impositions."[33] The offer of the nine-hour workday meant, still according to bins, a proof of the benevolence of entrepreneurs.[34]

The proposal of the nine-hour workday was not accepted by the workers and, on the same day, Xavier da Costa and Carlos Cavaco announced the foundation of Workers' Federation of Rio Grande do Sul (FORGS).[35] At first, anarchists did not participate in FORGS. It is not clear whether the libertarians were left aside at the foundation of the federation or if they decided not to adhere to it. Anarchists were already organized in the International Workers' Union, founded in the previous year, and the creation of FORGS was partly an opposition movement to them.[12] Despite the public demonstrations of the working class unions around the demand of the eight-hour workday, from the start of the general strike there were conflicts between anarchists and socialists. In one of the most tense moments of this conflict, the anarchists were expelled from a meeting that had been summoned by the Socialists at the headquarters of the Medret Union Society.[36] These conflicts were based on, as well as personal disagreements, various conceptions about the way the strike should be conducted, despite the common goal. Socialists wanted to subordinate the strike to their command, presenting themselves as the "bosses" or "directors" of the movement. The anarchists, in turn, rejected the idea of a centralized organization and defended the use of direct action.[37]

On October 8, entrepreneurs did publish in the press a warning announcing return to work from the 10th, establishing the nine-hour workday and stating that "if it is not accepted by the above time, they strictly declare that they will close their factories and will support the workers until a new deliberation."[38] On the same day, Xavier da Costa and Carlos Cavaco led a demonstration in the neighborhood of Navigantes, where about four thousand workers met to demonstrate opposition to the proposal of the industrialists. During the march, a group of female workers went to Cavaco's meeting offering flowers and asking him to go to the tribune, which he did, speaking between accounts of demonstrators.[39] Manifestations, however, were not always peaceful and orderly. On the 5th, a group of about a thousand strikers forced the staff who worked in the works of Caixa d'Agua and the Reservoir of Intendance, in Moinhos de Vento, to abandon the service under threat of beatings, and remained gathered there all afternoon, raising a large red flag at the top of the hill. On the same day, another group of strikers was able to avoid some workers to return to work at the spinning and tissues factory of Manoel Py, which addressed the police chief Pedro Mibielli to request the dispersion of the piquet line. Even in the presence of the police, the strikers maintained the attitude taken, and the factory could not be reopened.[40]

The female presence on the strike was highlighted by the local press. O Correio do Povo stated that the number of working women between the strikers was "huge, and about them, especially, they sought and managed to exert influence and dominance over the campaign promoters."[41] The large number of women strikers publicly evidenced a new reality: the growing hiring of women's labor in industries. The workers joined the movement very early and as a group. On October 5, the "feminine element of the proletariat" of the textile, clothing and candy industries joined workers on strike.[42] Submitted to a rigid discipline in factories and receiving lower wages than men, women had a visible participation in the public statements of the strike, marching together through the city streets demanding the eight-hour workday and tearing red dresses to make ties that they wore on their chests as a class symbol, contributing to these manifestations becoming "street and theater shows".[43] However, not all women were strike enthusiasts. On October 14, O Correio do Povo reported that women strikers organized "flocks to attack and assault the workers who returned to the factories."[41]

At the height of the strike, the number of striking workers reached five thousand.[44] However, not all sectors participated in the movement. On October 8, graphic workers held a meeting at the Vitório Emanuele II Vitary Association, aiming at the Foundation of the Graphics Union. Despite the large number of attendants, graphic workers decided not to adhere to the strike, since they already worked under the eight-hour regime. On the same day, Victor Barreto, owner of Progresso Industrial, invited his employees to a meeting at night, where they could declare themselves on strike, but that of his part, he was not willing to make deals. His employees, in turn, stated that they had nothing to complain, because they were satisfied not only with the job they had but also with the freedom of what they enjoyed, exalting the kind form by which they were treated by their bosses.[45]

On October 10, as they had announced, entrepreneurs reopened their establishments, supported by police forces.[46] However, most of the workers did not return to work. In the spinning and tissue company, which employed 400 workers, only 25 went to the service; in the factories of Alberto Bins, no one attended work.[47] The determination of workers in continuing the strike is explained by the difficulty of replacing their labor. Qualified workers knew that they could not be easily replaced in the limited local market, since most of the Porto-Alegrense industry employed only specialized labor.[48]

In the face of the impasse in the negotiations, Carlos Cavaco received two anonymous letters in a threatening tone, which advised him to abandon the leadership of the movement. Cavaco, as a form of defense and self-promotion, exposed the letters in the door of the Railway Cafe, drawing the attention of the curious.[49] Seeking to bring an end to the conflict, some entrepreneurs established separate agreements with their workers, lacking the agreement signed at the meeting on the 5th and indicating divergences between the employer group. On October 9, the workers of the quarries of Cesar Ognibene, Antônio Divan, Antônio Locatelli, Swedo Janson and Di Gian Pietro Giovanni released a manifesto in the Petit Journal, stating that they obtained the eight-hour workday and thanking the owners for the "grandiose and just grant". Gregory da Silva, Attilio Santa Catharina, João Bertotti, Hugo Ferrini and Oscar Teichmann, also agreed to reduce working time in their establishments. Nicolau Rocco, owner of the famous Rocco Confectionery, in addition to granting eight hours to his employees, opened a subscription to assist the strikers and contributed with 100,000 reis.[50]

Despite these partial victories, the economic situation of the strikers became delicate after more than a week stopped. Some butchers and retailers stopped selling IOUs to strikers, persuaded by entrepreneurs who intended to oblige workers to give in to hunger.[51] Trying to remedy economic difficulties, Carlos Cavaco conducted a literary conference for the benefit of strikers, "certain dealer" offered the workers ten bean bags and a FORGS commission started to prepare resistance funds, acquiring money, food and sending requests for help to other localities.[52] The Workers' Union of Pelotas and the workers of Cruz Alta answered the call of FORGS and sent resources to cheerful port strikers.[53]

Throughout the strike, the state and municipal governments were limited to the vigilance of the manifestations and the defense of employees who wanted to work, without intervening in negotiations between bosses and employees. Influenced by the positivism of Auguste Comte, the Gaucho governors defended the "incorporation of the proletariat to modern society," provided that within the established order, and the non-intrusion of the public authorities in the relations between capital and work.[38] The local press, especially O Correio do Povo, adopted a hostile posture in relation to the strike, accusing foreign workers of the rare cases in which the strikers crossed the line between peaceful protest and violence.[54] On October 16, for example, the newspaper noticed that two young employees of the wiring and tissue factories were assaulted by two strikers "of German origin," and accused "two German subjects" - the Socialists Wilhelm Koch and Zeller-Rethaller - of being the main "promoters and instigators of the movement".[55] Other moments, O Correio do Povo accused foreign strikers of ingratitude and disloyalty for protesting in the country that had given them prosperity and social mobility, using the "savings and properties obtained from wages earned here" to support them in a strike.[56]

Return to work

The economic difficulties faced by the strikers, the internal divergences between anarchists and socialists and the intransigence of the bosses ended up wearing the movement.[57] The police also banned the organization of workers' rallies at factories, so that they did not exercise coercion over those who abandoned the movement and returned to work. Xavier da Costa and Carlos Cavaco sought to give an honorable end to the movement. On October 13, Xavier da Costa met with Alberto Bins and proposed the reduction of the workday for eight hours and 45 minutes as a condition for the end of the strike. Entrepreneurs did not accept the proposal because they understood that the requirement of a quarter of an hour was just to humiliate the industrialists. Entrepreneurs decided to maintain the offer of nine hours and, if needed, close their establishments. According to Alberto Bins, the factories could re-establish the ten-hour workday and "oblige, by hunger, the workers return to work."[58]

On the 17th, according to the Jornal do Commercio, the workers who were on strike began to return to work, "how much some exalted seek all the means of deviating them from factories," although recognizing that some of the most important shopping and industrial establishments of the city - such as the property of Alberto Bins - remained stopped.[59] A little earlier, on the 14th, the same newspaper pointed to the existence of two postures between foreign workers relating to the continuity of the strike, mixing ethnic and ideological criteria, in stating that the Germans, "which are socialists, understand that they must return to work, accepting what has been proposed by industrialists", while the "Polish and Italians, anarchists, are opposed to work."[60]

On the 18th, entrepreneurs reported a notice reaffirming the maintenance of the nine-hour day and communicating that "will only be understood in regulation and other internal issues with commissions composed exclusively from their respective factories or works." Due to the intransigence of entrepreneurs, the strikers had no choice but to accept the nine hour day. Xavier da Costa and Carlos Cavaco, however, sought to preserve the organization of the working class and their leadership positions at the time of return to work. On the 19th, at the headquarters of FORGS, there was a meeting of commissions in charge of solving the continuation of the strike. Xavier da Costa and Cavaco defended the return to work.[61] For these leaders, the most important thing was to keep the gains already achieved by the movement: the reduction of the workday to nine daily hours, and the salary increase obtained by some sectors.[62]

The local press declared the end of the strike on October 21, announcing that the workers would return to work the following day.[63] However, many workers involved in the strike - especially the most qualified - did not want to go back to work, preferring to set up small workshops or transfer to other locations. The Union of the Hatters of Rio de Janeiro had to provide passages to the workers of this craft interested in working in that city, and on October 15, still during the movement, workers at the Tcheiron Hats factory departed to Rio. On October 26, After the end of the strike, some groups of workers embarked for Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Buenos Aires.[64] The marble workers, for their part, did not conform to the agreement and kept striking, managing to achieve the eight-hour workday.[65]

Despite this the Jornal do Commercio said, on October 18, that employees who returned to work were greeted "affectionately" by the bosses, the workers' press denounced a series of abuses and persecutions in the return to work. At the socks factory, a woman was fired for offering a bouquet of flowers to a chief striker and the bosses only accepted the return of their employees after each of them asked them "please"; at the factory spinning and tissues, the wages of the strikers were reduced and women complained of ill-treatment by their supervisors.[66] On November 15, the anarchist newspaper A Luta denounced that the entrepreneurs in the city decided to adopt "a kind of work libraries", a bosses' list of dismissed workers which indicated the reason for their dismissal, and which would be required by "too many bosses to whom the unemployed worker would ask for work."[67] In total, about one hundred workers were fired for having participated in the strike. In the face of the persecution, the possibility of restarting the stoppage. However, the strike was not resumed, since much of the employees were accepted in their factories or workshops and the nine-hour workday was fulfilled by their bosses.[51]

Results

The strike ended with partial victories for the workers, with the reduction of the working day to nine hours, and some sectors, such as that of the marble workers, were able to achieve the enforcement of the initial claim of the eight-hour workday.[68] The movement also reinforced class solidarity among the workers of Porto Alegre,[69] that for the first time occupied the public space of the city to claim their demands and made it visible the existence of a class conflict in a context marked by the advancement of capitalist production relations. On the other hand, entrepreneurs were also forced to organize and take ordinary steps when signing an agreement.[70]

According to historian Isabel Bilhão, the greatest achievement of the movement is "in the fact that it engenders the foundation of various workers' entities, the cohesion of some existing and the rearticulation of others." In addition to the establishment of the FORGS - which ultimately extended to the interior of Rio Grande do Sul and become the most important organization of the Gaucho working class - the movement saw the creation of the Marbles Union, the Masons' Union, the Union of Madeira Workers, the Union of Carpenters, the Union of Hatters, the Union of Weavers, the Union of Tailors and Grêmio Das Graphic Arts.[71] Among the associations already existing and who have been strengthened from the strike, were the International Workers' Union, where the anarchists were organized, and the Allgemeiner Arbeiter Verein, an association of German socialist workers.[72]

Although it strengthened the organization of the city's workers, on the other hand the strike also consolidated the split between anarchists and socialists. Socialists sought to maintain the movement within the limits of the constituted order, establishing trading channels with entrepreneurs and emphasizing the importance of partial achievements. After the end of the strike, the Socialists were politically strengthened, especially Francisco Xavier da Costa and Carlos Cavaco, who led the stoppage.[73] The anarchists, although they have driven movement with their demand of the eight-hour workday from the stoppage in the Aloys Friedrichs workshop, were allied with the direction of the strike and did not take part in the foundation of the FORGS. Even so, they continued to encourage the mobilization and organization of workers from the bases, challenging the proposals and attitudes of the socialists, especially the recognition of them as legitimate workers' interlocutors, and did not agree with the negotiated solution between entrepreneurs and the socialist leadership. Despite this, they saw the reduction of the workday to nine hours a partial achievement and recognized the importance of the movement to strengthen the class consciousness of the gauchos workers.[74]

References

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 183.

- 1 2 Schmidt 2005, p. 17.

- 1 2 Bak 2003, p. 185.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 200.

- 1 2 Bak 2003, p. 186.

- ↑ Bak 2003, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 196.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 202.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, pp. 13–14.

- 1 2 Schmidt 2005, pp. 14–16.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 185; Schmidt 2005, p. 16.

- 1 2 Bak 2003, p. 192.

- 1 2 3 Schmidt 2005, p. 16.

- 1 2 Bak 2003, p. 188.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 14.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 20.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 189; Schmidt 2005, p. 20.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 21.

- ↑ Bak 2003, pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 189; Schmidt 2005, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 19.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 190.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 23.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, pp. 28–30.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 30.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 32.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 38.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 39.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Petersen 1993, p. 304.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 52.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, p. 49; Petersen 1993, p. 305.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 43.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 45.

- 1 2 Schmidt 2005, p. 54.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 58.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, p. 50.

- 1 2 Petersen 2001, p. 197.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 210.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 211-212.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, pp. 89–91.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, p. 51.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 63.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, p. 52.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 193.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, p. 53; Schmidt 2005, p. 66.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, pp. 63–64.

- 1 2 Schmidt 2005, p. 75.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 64.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 74-75.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 207.

- ↑ Petersen 2001, p. 196.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 208.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 67.

- ↑ Petersen 1993, p. 305.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, p. 60.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 70.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, p. 62.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, p. 61.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Petersen 2001, p. 198.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 74.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, p. 63.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, p. 64.

- ↑ Bak 2003, p. 218.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 79.

- ↑ Bilhão 1999, p. 65.

- ↑ Petersen 2001, p. 207.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, p. 80.

- ↑ Schmidt 2005, pp. 80–81.

Bibliography

- Bak, Joan (2003). "Classe, etnicidade e gênero no Brasil: a negociação de identidade dos trabalhadores na Greve de 1906, Porto Alegre". Métis: História & Cultura (in Portuguese). Caxias do Sul. 2 (4): 181–224. ISSN 2236-2762. OCLC 656555593.

- Bilhão, Isabel Aparecida (1999). Rivalidades e solidariedades no movimento operário (Porto Alegre, 1906-1911) (in Portuguese). Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS. ISBN 978-85-7430-087-0. OCLC 254114611.

- Petersen, Sílvia Regina Ferraz (1993). "As greves no Rio Grande do Sul (1890-1919)". In Dacanal, José Hildebrando; Gonzaga, Sergius (eds.). RS: Economia e política (in Portuguese). Porto Alegre: Mercado Aberto. pp. 277–327. ISBN 978-85-2800-234-8.

- Petersen, Sílvia Regina Ferraz (2001). "Que a união operária seja nossa pátria": História das lutas dos operários gaúchos para construir suas organizações (in Portuguese). Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS. ISBN 978-85-7025-597-6. OCLC 51758463.

- Schmidt, Benito Bisso (2005). De mármore e de flores: A primeira greve geral do Rio Grande do Sul (Porto Alegre, outubro de 1906) (in Portuguese). Porto Alegre: Editora da UFRGS. ISBN 978-85-7025-800-7. OCLC 68187868.