| Host city | Berlin, Germany |

|---|---|

| Countries visited | Greece, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia (Serbia), Hungary, Austria, Czechoslovakia (Czechia), Germany |

| Distance | 3,187 km |

| Torch bearers | 3,331 |

| Start date | 20 July 1936 |

| End date | 1 August 1936 |

| Torch designer | Walter Lemcke |

| No. of torches | 3,840 |

| Part of a series on |

The 1936 Summer Olympics torch relay was the first of its kind, following on from the reintroduction of the Olympic Flame at the 1928 Games. It pioneered the modern convention of moving the flame via a relay system from Greece to the Olympic venue. Leni Riefenstahl filmed the relay for the award-winning but controversial 1938 film Olympia.

Organization

The Olympic flame was introduced to the modern Games in 1928 when it burnt atop a pillar above the stadium in Amsterdam. Four years later the same was repeated in Los Angeles. At both of these events the flame was lit on site at the stadium.[1]

Carl Diem used the idea of the torch relay devised for the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin by a Jewish archaeologist and sports official, Alfred Schiff. According to the official report for the Games, the torch relay was conceived as a publicity stunt to increase awareness for the Games. The process was ratified by the International Olympic Committee[1] and has been repeated at all the Games that have followed.[2]

Diem and the organizing team realized that there would need to be very detailed plans in order to successfully complete the relay to a standard that would satisfy both themselves and the ruling Third Reich. At the time they were unsure about exactly how they could use the sun's rays to start the fire as well as how to create a torch that would remain alight whatever the conditions. Research was therefore required into the specialist technologies that would be needed. The route itself would need development and the path down from Olympia was deemed too difficult to access. The organising committees therefore agreed that new roads would be built to ensure that the relay got off to the best possible start.[3]

Political significance

Adolf Hitler saw the link with the ancient Games as the perfect way to illustrate his belief that classical Greece was an Aryan forerunner of the modern German Reich.[4][5]

"The sportive, knightly battle awakens the best human characteristics. It doesn't separate, but unites the combatants in understanding and respect. It also helps to connect the countries in the spirit of peace. That's why the Olympic Flame should never die."

— Adolf Hitler, commenting on the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games[6]

The event was designed to demonstrate the growing influence and power of the Third Reich. It was internationally viewed as a great success,[4] sufficient for it to be replicated in all Games thereafter.[2][7]

Leni Riefenstahl, a film-maker admired by Hitler,[2] filmed the relay for the 1938 release Olympia. While the film is often seen as a prime example of Nazi propaganda,[6] it has also been hailed as one of the greatest films of all time[8] and won many awards upon its release.[9]

Relay elements

Torch

Sculptor Walter Lemcke designed the 27 cm wood and metal torches. German manufacturer Krupp produced 3,840 copies for the runners, over 500 more than would be needed.[10] It was designed with two fuses to help it cope with different weather conditions and could stay alight for ten minutes, longer than each section of the route.[1]

Route

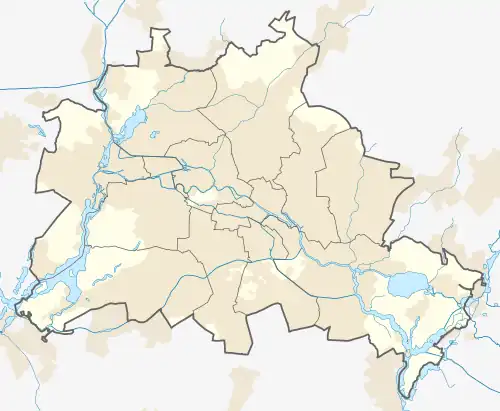

On 20 July 1936[1] the Olympic flame was lit in Greece by a concave mirror made by German company Zeiss.[4] The Nazi Party wanted to demonstrate their organisational prowess and enhance their influence on various countries along the route of the relay. The torch travelled through south-eastern and central European countries to demonstrate and enhance their influence.[4] The National Olympic Committees (NOCs) of the countries along the route all agreed to support the relay which would pass through Greece, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Austria, and Czechoslovakia and then Germany.[1] These countries would fall under Nazi domination as the second World War began just over three years later.[2] In Austria, a country that would be annexed into the Third Reich less than two years after the relay, the torch was met by major pro-Nazi public demonstrations.[4]

In all the torch was transported over 3,187 kilometres by 3,331 runners in twelve days and eleven nights from Greece to Berlin. Much of the route was split into kilometre-long sections and it was anticipated that each runner would traverse that distance in five minutes, though some leeway was given to allow for difficult terrain and sparsely populated areas.[1] The names of most of the torch bearers, all of whom were male,[2] were not recorded.[11]

Route in Greece

July 20:

July 21:

July 22:

July 23:

July 24:

July 25:

Route in Europe

July 25 (Bulgaria):

July 26 (Yugoslavia):

July 27 (Yugoslavia):

July 28 (Yugoslavia):

July 28 (Hungary):

- Szeged, Kiskunfélegyháza, Kecskemét, Sári, Soroksár, Budapest

July 29 (Hungary):

July 29 (Austria):

July 30 (Austria):

- Maissau, Horn, Göpfrür, Waidhofen, Heidenreichstein, Reingers

July 30 (Czechoslovakia):

July 31 (Czechoslovakia):

Route in Germany

| Date | Map |

|---|---|

|

July 31 (day 1): Pirna |

|

|

July 31 (day 1): Elsterwerda |

|

|

August 1 (day 2): Berlin |

Runners per country

| # | Country | Runners |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Greece | 1,108 |

| 2 | Bulgaria | 238 |

| 3 | Yugoslavia | 575 |

| 4 | Hungary | 386 |

| 5 | Austria | 219 |

| 6 | Czechoslovakia | 282 |

| 7 | Germany | 267 |

Lighting of the cauldron

Two urns in the centre of Berlin, within two long rows of large swastika flags, were lit by 400m-runner Siegfried Eifrig on 1 August 1936.[4][11] The urns burnt for the duration of the Games and served as the starting point for the final relay runner. Fritz Schilgen, a three time 1500m champion, was suggested by former German athletics president Karl Ritter von Halt as the final runner. Schilgen, viewed as a "symbol of German sporting youth",[3] was accepted by the three advisory boards. One of these, the aesthetics commission, included film-maker Riefenstahl on the panel.[13]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Torches". olympic-museum.de. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Heald, Claire (9 May 2012). "London 2012: What is the Olympic torch relay?". BBC News. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- 1 2 "The Olympic flame and torch relay" (PDF). The Olympic Museum. 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bowlby, Chris (5 April 2008). "The Olympic torch's shadowy past". BBC News. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ Hines, Nico (7 April 2008). "Who put the Olympic flame out?". London: timesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- 1 2 Weigant, Chris (14 April 2008). "The Olympic Torch Relay's Nazi Origin". Huffington Post. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ Schwarcz, Joe (27 July 2012). "London 2012 torch 'lighter, brighter, safer'". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ↑ "All-Time 100 Movies". Time. 12 February 2005. Archived from the original on May 23, 2005. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ "Leni Riefenstahl (1902–2003) • Part 2". The German Way & More". Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ "London 2012: Torch relay heading for 1,000 places". BBC News. 18 May 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- 1 2 "Siegfried Eifrig – Last Berlin Torch Bearer from 1936 Dies". German Road Races. Archived from the original on 2014-01-04. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ "The XI Olympic Games Berlin, 1936 Official Report Volume I" (PDF). library.la84.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ↑ "Fritz Schilgen made Olympic history – the final runner of the Olympic torch relay in Berlin 1936". BMW Berlin Marathon. 18 September 2005. Retrieved 30 July 2012.