| |

| Date | May–December 2022 |

|---|---|

| Location | Sudan |

The 2022 Sudan floods saw the figure for flood-affected people in Sudan had exceeded the figure for 2021, rising to 314,500.[1] From 2017 to 2021, there were 388,600 people affected by floods annually.[1]

Description

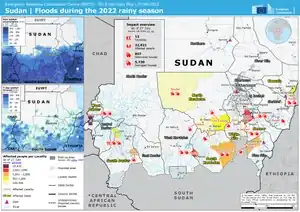

Since May 2022, the north-eastern African country of Sudan has been in the rainy season. The rainy season in Sudan usually starts in June and ends in September. Peak rainfall and flooding is between August and September.[1] The level of the Nile has risen rapidly to the highest level of the last 70 years because of the persistent heavy rains.[2] The Nile level continues to rise and reached a crucial phase in the capital Khartoum. As of 23 August, the level of Nile stands at 16.42 meters, where the critical stage is 16 meters and flooding 16.5 meters.[3] According to reports, more than 4,800 livestock have been lost and nearly 5,100 hectares of land have been damaged or destroyed. This could lead to food production being hampered and contributing to high food prices and lead to a deterioration in food security, exacerbating an already perishing food emergency.[4][5] Torrential rains destroy the roads to rural areas, cutting off supply lines in need of humanitarian assistance.[6]

Alongside the floods, Sudan is in a situation of political turmoil and economic crisis, among other things. The government was taken control of via military coup by Sudanese military, which is led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan on 25 October 2021.[7] More than hundreds of thousands of people have been displaced since this military coup, with severe political, economic and social crises, heavy rains and floods occurring at the same time. The army was compelled to dissolve the transitional government of Abdalla Hamdok, in order to help reduce human casualties and economic losses.[8] But floods and coups still seriously exacerbate Sudan's economic crisis.The flood has contributed billions of dollars of economic damage to the people of Sudan.[8][9]

Impact

The effects of flooding have been vast, hitting 16 of Sudan's 18 states, with South Darfur, Gedaref, Central Darfur, White Nile, and Kassala being the worst hit.[10]

The physical impacts of flooding vary from place to place and include:

- Building damage or destruction (including homes, resulting in displacement; schools, with consequent suspending of school year start; medical facilities, reducing access to healthcare; shops) [11][12][13]

- Livestock killed or carried away [11][12]

- Loss of crops due to agricultural fields’ inundation [13][12]

- Damage to/destruction of roads has meant help cannot reach those in need, and restricted access to markets and health facilities.[14][13][12]

- Loss of belongings, including identity documents.[13]

- Livelihoods affected in connection with above

Displacement

Flooding occurring from May to 20 October 2022 has resulted in 97,227 newly displaced individuals (54% of whom are women) with the highest figures in Gedaref (35%), North Darfur (17%), South Darfur (13%) and River Nile (10%).[15]

IDPs are staying in a variety of temporary housing solutions: erecting shelters close to their previous homes in areas with less damage, staying with others, sheltering in schools (where still standing), others are sleeping in the open air.[16][14][11][17][13]

Sudan has a high population of refugees (1.1M) and IDPs (3.7M). [18] Between January and September 2022, inter-communal violence and armed attacks (which is ongoing) caused the displacement of more than 211,000 people.[19] Therefore, many of those displaced by the floods were already IDPs.[16]

South Darfur has the highest concentration of individuals in need, totalling 1,703,267 IDPs, refugees, returnees and other vulnerable people.[20] The state hosts 1.1M IDPs and 30 IDPs camps.[20] Flooding at the Kalma IDPs camp (population: 126,200) has made drinking water unsafe due to contamination and spoiled food stocks.[21] Homes, WASH facilities and school structures were also damaged.[21]

Immediate mortality and morbidity

Contaminated water, overcrowded shelters, displacement, and inadequate sanitation can all arise following floods, but public health initiatives can stop these things from happening.[22]

Overall, there is not a lot of definitive data on post-disaster disease and the literature and reporting on this is poor. However, conclusions can be drawn from a compilation of other relevant reports in most cases. Floods exacerbate acute episodes of chronic and non-communicable diseases as well as the management of these conditions.[22] The availability of personal and medical services is impacted by disasters, which has an impact on the management of chronic and non-communicable diseases as well as the continuity of care.[23] The majority of mortality studies' findings mirror this, and it may be linked to a rise in the number of persons seeking medical attention. For the post-disaster era, it is crucial to establish the care requirements for those with chronic or non-communicable diseases as well as the anticipated disease burden.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Sudan: Humanitarian Update, September 2022 (No. 08) - Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ↑ "苏丹尼罗河水位上升至70多年来最高记录_洪水_受灾_报告". www.sohu.com. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ↑ "(Updated) Sudan – Flood Death Toll Rises, Nile Climbs Above Alert Level in Khartoum – FloodList". floodlist.com. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ↑ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Devastation in South Sudan following fourth year of historic floods". UNHCR. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ↑ "Sudan: Weekly Floods Round-up, No. 07 (19 September 2022) - Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ↑ AfricaNews (2022-09-15). "Sudan floods kill 134 people, destroy 16 900 homes". Africanews. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ↑ "October–November 2021 Sudanese coup d'état", Wikipedia, 2022-10-15, retrieved 2022-10-30

- 1 2 "Severe flooding kills scores in Sudan - Al-Monitor: Independent, trusted coverage of the Middle East". www.al-monitor.com. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ↑ "苏丹暴雨引发洪水 全国近23万人受灾 | 早报". www.zaobao.com.sg (in Simplified Chinese). Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ↑ "Sudan". reports.unocha.org. Retrieved 2022-10-29.

- 1 2 3 https://assessments.hpc.tools/attachments/48b2fa61-69d7-4f17-b616-888ad41c57cd/20220824%20_Inter-Agency%20Flood%20Assessment%20Report_Central%20Darfur_%20Draft.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 https://assessments.hpc.tools/attachments/a2b11fa6-0cfe-4fcf-b0e4-1d38c774deb1/20220821_Inter-Agency%20Flood%20Assessment%20Report_Sennar%20State.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Inter-Sectoral/ Agency Assessment: Impact Of Flooding In Gedaref State | Assessment & Analysis Knowledge Management Platform". assessments.hpc.tools. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- 1 2 "Sudan floods: No sign of relief from torrential rains as 23 more people die". Radio Dabanga. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ↑ "Sudan - Rainy Season Summary (May–October) (Update 009) | Displacement". displacement.iom.int. Retrieved 2022-10-29.

- 1 2 "Africa Today - Lesotho holds parliamentary elections - BBC Sounds". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- ↑ "ACAPS Briefing Note - Sudan: Floods, 09 September 2022 - Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. Retrieved 2022-10-29.

- ↑ https://unh.cr/63505e3bdc

- ↑ "Sudan Situation Report, 17 Oct 2022 - Sudan". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2022-10-30.

- 1 2 "Sudan: South Darfur State Profile (Updated March 2022) - Sudan | ReliefWeb". reliefweb.int. Retrieved 2022-10-29.

- 1 2 darfur (2022-08-12). "Dangerous Living Situations at Kalma Camp in South Darfur Nyala". Darfur Monitors. Retrieved 2022-10-29.

- 1 2 Saulnier, Dell D.; Brolin Ribacke, Kim; von Schreeb, Johan (October 2017). "No Calm After the Storm: A Systematic Review of Human Health Following Flood and Storm Disasters". Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 32 (5): 568–579. doi:10.1017/S1049023X17006574. ISSN 1945-1938. PMID 28606191.

- ↑ Alderman, Katarzyna; Turner, Lyle R.; Tong, Shilu (2012-10-15). "Floods and human health: a systematic review". Environment International. 47: 37–47. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2012.06.003. ISSN 1873-6750. PMID 22750033.