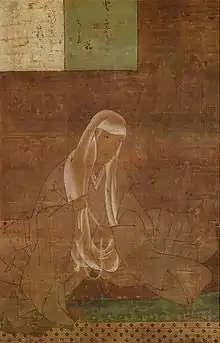

Abutsu-ni | |

|---|---|

Abutsu-ni | |

| Native name | 阿仏尼 |

| Born | 1222 |

| Died | 1283 (aged 60–61) |

| Notable work | Izayoi nikki (Diary of the Waning Moon) |

| Spouse | Fujiwara no Tameie |

| Children | Kyōgoku Tamenori, Reizei Tamesuke |

Abutsu-ni (阿仏尼, c. 1222 – 1283; the -ni suffix means "nun") was a Japanese poet and nun. She served as a lady-in-waiting to Princess Kuni-Naishinnō, later known as Empress Ankamon-in.[1] In approximately 1250 she married fellow poet Fujiwara no Tameie. She had two children with him. Following his death in 1275, she became a nun. A dispute over her son's inheritance led her, in either 1277 or 1279, to travel from Kyoto to Kamakura in order to plead on her son's behalf.[2] Her account of this journey, told in poems and letters, was published as Izayoi nikki (Diary of the Waning Moon or Journal of the Sixteenth-Night Moon), her most well-known work.[3]

Early life

Abutsu-ni's birth name and parentage are unknown. She was adopted at a young age by Taira no Norishige, the nominal governor of Sado Province. As his daughter she served in the court of Princess Kuni-Naishinnō, later Empress Ankamon-in. During this time she was known as Ankamon-in no Shijō and Ankamon-in Emon no Suke.[2] Also during her time at court, she gave birth to three children with unknown parentage: two sons, Ajari and Rishi, and a daughter, Ki Naishi. Both sons became Buddhist clergy members and Ki Naishi became a lady-in-waiting to a consort of Emperor Kameyama.[3] From later correspondence compiled in the Izayoi nikki, it is revealed that she also had two sisters, one older and one younger.[4]

Marriage and inheritance dispute

In or around 1250, Abutsu-ni married Fujiwara no Tameie, whom she likely met while working on a commissioned copy of The Tale of Genji. Together they had two sons: Tamesuke born in 1263, and Tamenori born in 1265. Tamesuke later took the surname of "Reizei", founding the Reizei family of poets.[3] Following Tameie's death in 1275, she shaved her head and took on the monastic names of Abutsu and Hokurin-zenni.[1]

Before marrying Abutsu-ni and having children with her, Tameie had bequeathed much his estate to his eldest son from another relationship, Tameuji. Before his death, Tameie issued two documents attempting to transfer rights to a portion of the estate from Tameuji to his eldest son with Abutsu-ni, Tamesuke. This portion was the Hosokawa estate, and consisted of a manor located in Harima Province. Following Tameie's death, Tameuji refused to transfer the Hosokawa estate to Tamesuke, beginning a protracted legal battle.[4]

On behalf of her son, Abutsu-ni appealed to both the imperial court and the Kamakura shogunate. She personally traveled to Kamakura in 1279 to speak to the shogunate about the dispute. She accused Tameuji of "unfilial conduct" and challenged his refusal to accept Tameie's amendments to his will. A decision on the case was delayed by the shogunate's preoccupation with fending off the Mongol invasions of Japan which occurred in 1274 and 1281, and Abutsu-ni died in Kamakura in 1283, still awaiting a verdict. The government eventually decided against Tamesuke in 1286.[4]

Works

Forty-eight of Abutsu-ni's poems appear in imperial anthologies of Japanese poetry. Of these, she first appears in the Shokukokin Wakashū, compiled by her husband. Fifty-nine more poems of Abutsu are also found in a private anthology entitled Fubokushō.[3]

The Izayoi nikki (Diary of the Waning Moon), her most well-known work, recounts her trip to Kamakura on behalf of Tamesuke and consists mostly of poems and correspondence from this time. It was available in print as early as 1659 and has enjoyed continued popularity since then, appearing in many collections of Japanese literature and receiving considerable scholarly attention.[4]

Abutsu is also generally accepted to be the author of Utatane no ki (Record of a Nap), which recounts a failed love affair from 1238.[2] Other works include Yoru no tsuru (The Night Crane), a treatise on poetry written for her son Tamesuke, and Niwa no oshie (Garden Instructions), a letter to her daughter.[3]

References

- 1 2 Papinot, Edmond (1964). Historical and Geographical Dictionary of Japan. New York: F. Ungar Publishing Co. p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Dodansha. 1983. pp. 5–6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mulhern, Chieko Irie (1994). Japanese Women Writers: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 3–8. ISBN 9780313254864. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Resichauer, Edwin O. (December 1947). "The Izayoi Nikki (1277–1280)". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 10 (3/4): 255–387. doi:10.2307/2718221. JSTOR 2718221.