Adamson Tannehill | |

|---|---|

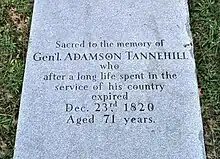

Gravestone of Adamson Tannehill, Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania's 14th district | |

| In office March 4, 1813 – March 3, 1815 | |

| Preceded by | Seat newly established |

| Succeeded by | John Woods |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 23, 1750 Frederick County, Province of Maryland, British America |

| Died | December 23, 1820 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Allegheny Cemetery, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, US |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse | Agnes Morgan or Agnes Maria or Agnes Heth |

| Profession | Military officer, politician, civic leader, and farmer |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Battles/wars | |

Adamson Tannehill (May 23, 1750 – December 23, 1820) was an American military officer, politician, civic leader, and farmer. Born in Frederick County, Maryland, Tannehill was among the first volunteers to join the newly established Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, serving from June 1775 until 1781. He was promoted to captain and was commander of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment, the longest-serving Continental rifle unit of the war. After the conflict, Tannehill settled in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, his last military posting of the war. He was active in the Pennsylvania state militia, rising to the rank of major general in 1811. Tannehill served as a brigadier general of United States Volunteers in the War of 1812.

Tannehill was an early citizen of Pittsburgh and a Pennsylvania politician who held several local, state, and national appointed and elected offices. These included one term as a Democratic-Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1813 to 1815 and president of the Pittsburgh branch of the Bank of the United States starting in 1817 until his death in 1820. He also served on the founding boards of several civic and state organizations. In late 1800, Tannehill, while a justice of the peace, was alleged to have charged more than was allowed by law for two probates and was convicted of extortion. He was reinstated to office shortly after by the governor of Pennsylvania.

Tannehill died in 1820 near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He was buried at his Grove Hill home outside Pittsburgh and later reinterred in Allegheny Cemetery in 1849.

Early years

Adamson Tannehill was born May 23, 1750, in Frederick County, Maryland,[1][2] the oldest of nine children born to John Tannehill, owner of a tobacco plantation, and Rachel Adamson Tannehill.[2] Adamson's maternal grandfather took a special interest in the grandchild who bore his name, and he provided "such pecuniary assistance as to secure a fine education" for him.[3] Little else is known of Adamson's youth and upbringing. No portraits of him are known to exist; family records state that as an adult he "was six feet in height, well proportioned and of commanding appearance".[4]

Revolutionary War service

At the age of 25, Tannehill was among the first volunteers to enlist in one of the earliest American military units to form when the American Revolutionary War started in the spring of 1775.[5] He served in the Continental Army, initially as a sergeant in Captain Thomas Price's Independent Rifle Company,[5] one of the original ten independent rifle companies authorized by the Continental Congress.[6] He received his commission dated January 1, 1776, as a third lieutenant,[7] while serving at the siege of Boston.[3] In mid-June the same year, Tannehill and his company were incorporated into the newly organized Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment, when he advanced to second lieutenant.[8]

In mid-November 1776, a large portion of Tannehill's regiment was captured or killed at the Battle of Fort Washington on northern Manhattan Island.[9] The remainder—about one-third of the unit including Tannehill—continued to serve actively in the Continental Army.[10] They participated in the battles of Trenton and Princeton and the Forage War.[11] In the late spring of 1777, they were administratively attached to the 11th Virginia Regiment because of the losses suffered by their rifle regiment.[12] Tannehill was promoted to first lieutenant on May 18, 1777,[13] and the following month he was attached to the newly organized Provisional Rifle Corps commanded by Colonel Daniel Morgan.[14] This regiment-size force of about 500 men played a major role in the Battles of Saratoga in late 1777 and a peripheral role in the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778.

Tannehill was probably detached from the rifle corps in mid-1778 and returned to the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment (his permanent unit).[15] This occurred when Lieutenant Colonel Moses Rawlings, the regiment's commander, was marshaling the remnants of his unit and recruiting new members while stationed at Fort Frederick, Maryland.[16] Rawlings had been captured at the Battle of Fort Washington and recently exchanged from British captivity.[17] In early 1779 Tannehill and the regiment were assigned to Fort Pitt of present-day western Pennsylvania where they supplemented other Continental forces engaged in the defense of frontier settlements of the war's western front from Indian raids.[18][19][20] The high mark of this effort was the 600-man Brodhead Campaign against hostile Mingo and Munsee Indians conducted in the late summer of 1779.[21]

Tannehill was promoted to captain on July 29, 1779,[22] and by late 1780 commanded the regiment and was commandant of Fort McIntosh located in western Pennsylvania northwest of Fort Pitt.[23][24] He was discharged from service on January 1, 1781,[25] when several regiments, including Tannehill's, were disbanded as a result of Congress's major 1781 reorganization of the Continental Army instituted largely to reduce expenditures.[26] The Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment was the longest-serving Continental rifle unit of the war.[27] Tannehill was admitted as an original member of the Society of the Cincinnati in the state of Maryland when it was established in 1783.[28][29]

Relocation to Pittsburgh

After his Revolutionary War service, Tannehill settled in frontier Pittsburgh, as did many other Revolutionary War officers.[30] He initially engaged in farming and was a tavern owner[31][32] and vintner.[33] He was also a significant landholder and a "large buyer"[34] of land lots in early Pittsburgh—land purchased directly from the heirs of William Penn.[35] From 1784 until around 1792, Tannehill owned and operated the riverfront Green Tree Tavern and Inn, residing in the adjacent house, both located midblock between Market and Wood Streets in Pittsburgh.[35][36] In around 1792, he moved to his new Grove Hill estate, which became popular as a local center for political meetings while owned by Tannehill.[37] The property was located on Grant's Hill just northeast of Pittsburgh. One of the buildings at Grove Hill, known as "the Bowery", was the site of large annual social gatherings hosted by Tannehill where citizens of Pittsburgh came together each Fourth of July "to hail with joyful hearts the day that gave birth to the liberties and happiness of their country".[37][38] Tannehill lived at Grove Hill until his death in 1820.[39]

Early public career

Tannehill began public service no later than 1794 when the borough of Pittsburgh was established.[40] That year, he was appointed president of the Pittsburgh Fire Company[41] and elected one of three surveyors of Pittsburgh.[42] In March 1790, Tannehill had unsuccessfully solicited a public appointment in the administration of President George Washington by writing to Washington's personal secretary, Tobias Lear, who had visited Pittsburgh and lodged with Tannehill at his inn four years before.[43] In his note, Tannehill mentioned that Washington "has some acquantance [sic] of me, which may probably have some weight," referring to instances of direct interaction the two men had during the American Revolution.[3]

Sometime before 1794, Tannehill was appointed a justice of the peace of Allegheny County,[41] an admistrative unit that included Pittsburgh. In October 1800, he was temporarily removed from this office after being convicted of extortion related to an event that occurred five years before in which he was alleged to have charged two shillings more than was allowed by law for two probates.[44] He was issued a reprimand and fined fifty dollars.[44] Tannehill was quickly reinstated to office in January 1801 by Governor Thomas McKean, the former chief justice of Pennsylvania, was refunded his fine,[44] and subsequently held several prominent elected and appointed public offices. Tannehill believed the charges against him had marred his reputation and vehemently disclaimed any guilt for the rest of his life. His resentment toward whom he called "two of the most unprincipled scoundrels who ever appeared before a Court of Justice" and what he characterized as their "false swearing and vile slander" was still strong 15 years later when he reflected on the affair in his will.[45]

Tannehill was active in the state militia, serving as a lieutenant colonel in the Westmoreland County militia starting in 1788.[35] On August 3, 1811, Pennsylvania Governor Simon Snyder promoted Tannehill to major general of a Pennsylvania militia division drawn from Allegheny, Armstrong, and Indiana counties.[35]

Later public career

Tannehill served as a founding member of the board of directors of the Pittsburgh branch of the Bank of Pennsylvania, starting in 1804. (This was the first bank established in Pittsburgh and the first one west of the Allegheny Mountains.)[46] He was then appointed by the Pennsylvania legislature as one of five turnpike commissioners for the state starting in 1811.[47] Tannehill was also chosen by the state legislature as an elector of the 1812 federal Electoral College for the state of Pennsylvania.[48]

After the War of 1812 broke out, Tannehill served as a brigadier general commanding four infantry and rifle regiments of United States Volunteers.[49] His military duties during the limited duration of the conflict in western Pennsylvania lasted from September 25 to December 31, 1812.[1]

Meanwhile, outside of public office, Tannehill served as a trustee of the First Presbyterian Church of Pittsburgh starting in 1787.[50][51] He was also a member of the fraternal Tammany Society, which was founded after the American Revolution in several American cities, including Pittsburgh.[52] The society focused on the celebration of American identity and culture. Members of the society in its earliest years closely allied themselves with the Democratic-Republican party of Thomas Jefferson. Consequently, when Jefferson announced his intent to withdraw from public service in 1808, Tannehill, in his capacity as Grand Sachem (high official) of the Pittsburgh Tammany Society, wrote to "Brother" Jefferson, expressing "heartfelt regret" over his "resolution to retire from the duties of protecting thy children [of this tribe]".[53][54]

U.S. House of Representatives

Although Pittsburgh was a stronghold of the Federalist Party in the city's earliest years, between 1798 and 1800 the rival Democratic-Republican Party began to prosper under such men as Adamson Tannehill, who had become chairman of the city's Republican party by 1800.[55] The high point of Tannehill's active political career was his election as a Democratic-Republican to the Thirteenth U.S. Congress on October 13, 1812.[1] Tannehill was elected to serve Pennsylvania's newly established 14th congressional district with 48 percent of the vote, defeating Federalist John Woods and Democratic-Republican John Wilson, who received 39.3 and 12.7 percent of the vote, respectively.[56] Tannehill served from March 4, 1813, to March 3, 1815,[1] casting 322 votes and missing 30.[57]

Tannehill ran for reelection on October 11, 1814, again as a Democratic-Republican. He lost his reelection bid, receiving 49.5 percent of the vote; his opponent, John Woods, whom he had defeated two years earlier, won with 50.5 percent of the vote.[58]

Following his tenure in Congress, Tannehill served as president of the Pittsburgh branch of the Bank of the United States starting in 1817[59] and ending with his death in 1820.

Death

Tannehill died at his Grove Hill home just outside Pittsburgh on December 23, 1820, aged 70 years and 7 months.[3][1] He was survived by his wife, Agnes M. Tannehill,[60][61][62] and his ward, Sydney Tannehill Mountain.[63] Adamson and Agnes had no children.[64] Tannehill was interred at his Grove Hill home,[65] as specified in his will.[66] His 1820 obituary relates that "his remains were accompanied to the grave by a large concourse of his fellow citizens and were interred with military funeral honors by two...Volunteer Corps" of the Pittsburgh area.[67]

Tannehill's body was reinterred in Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh on April 26, 1849,[68] because urban spread and city road construction necessitated moving his Grove Hill grave. The archive files of a prominent Pittsburgh newspaper provide detail on this reinternment: "after the big fire in 1845, when [the Pittsburgh city] council extended the city limits to take in the farms on what is now the Hill district…it was found that in extending Wylie avenue, Colonel Adamson Tannehill's grave would be between the curbs…About 1851 [sic] [the] council decided to remove the colonel's remains to Allegheny cemetery. The Tannehill family objected, but [then] agreed to make the transfer themselves."[69]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 "United States Congress". Archived from the original on May 10, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023..

- 1 2 Coe, pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 3 4 Coe, p. 3.

- ↑ Coe, p. 6.

- 1 2 Maryland Historical Society (1927), p. 275.

- ↑ Ford (1905), pp. 89–90 Archived January 28, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Adamson Tannehill papers, 1776 commission. Third lieutenant was the lowest commissioned rank in Continental Army rifle units, whereas in infantry units it was ensign.

- ↑ Ford (1906), p. 540 Archived January 28, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Rawlings to Washington (August 1778).

- ↑ Hentz, p. 134 Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hentz, pp. 135–137 Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hentz, pp. 136–137 Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Heth (May 18, 1777).

- ↑ Long's Provisional Rifle Co. pay roll (July 1777).

- ↑ Hentz, p. 138 Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hentz, pp. 138–139 Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Rawlings to Congress (November 28, 1785).

- ↑ Ford (1909), p. 104 Archived January 28, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hentz, pp. 139–140 Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 196, 253.

- ↑ Hentz, p. 140 Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Ford (1909), pp. 895–896 Archived January 28, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hentz, p. 141 Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kellogg, p. 289.

- ↑ Maryland Historical Society (1900), p. 365 Archived July 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Wright, p. 153 Archived October 28, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hentz, p. 129 Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Metcalf, p. 304.

- ↑ "American Revolution Institute". Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ↑ Foster, p. 16 Archived April 30, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Boucher, p. 376 Archived April 30, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Dahlinger (1919), p. 18 Archived April 29, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Killikelly, p. 111 Archived May 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Evans, p. 126 Archived September 17, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, p. 169 Archived August 13, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Darlington and others, p. 301 (map of Pittsburgh in 1795).

- 1 2 Mulkearn and Pugh, p. 28 Archived September 28, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Miller, p. 26 Archived September 28, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chalfant, pp. 86–87 Archived April 27, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Dahlinger (1916), p. 24 Archived May 19, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Dahlinger (1916), p. 130 Archived May 19, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Killikelly, pp. 114, 116 Archived May 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Twohig, pp. 208–209 Archived September 5, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 Dahlinger (1916), pp. 130–131 Archived May 19, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Chalfant, pp. 86–88 Archived April 27, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Thurston, p. 251 Archived April 29, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Walkinshaw, p. 65 Archived May 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Pennsylvania 1812 Electoral College". Archived from the original on September 17, 2023. Retrieved September 13, 2023.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 401. Archived August 22, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Killikelly, p. 362 Archived May 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Harper, p. 754 Archived May 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Baldwin, p. 150.

- ↑ Adamson Tannehill to Thomas Jefferson (January 13, 1808).

- ↑ Ford (1916), pp. 157–158. Archived September 28, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Everett, pp. 13, 37 Archived September 17, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "U.S. Congress, Pennsylvania 1812". Archived from the original on July 11, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ↑ "Govtrack". Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ↑ "U.S. Congress, Pennsylvania 1814". Archived from the original on July 11, 2023. Retrieved July 11, 2023.

- ↑ Killikelly, p. 263 Archived May 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Coe, p. 4. This source identifies Agnes Tannehill's maiden name as "Morgan".

- ↑ Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, p. 169 Archived August 13, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. This source identifies Agnes Tannehill's middle name as "Maria".

- ↑ Sons of the American Revolution, p. 92. This source records Agnes Tannehill's maiden name as "Heth".

- ↑ Chalfant, p. 88 Archived April 27, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Tannehill, pp. 41–42 Archived August 27, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sons of the American Revolution, p. 92.

- ↑ Chalfant, p. 87 Archived April 27, 2023, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Coe, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ "Allegheny Cemetery". Archived from the original on October 8, 2023. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ Christman, p. 6.

References

- Adamson Tannehill papers. 1776 Commission. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center.

- Adamson Tannehill to Thomas Jefferson (January 13, 1808). Thomas Jefferson Collection. San Marino, California: The Huntington Library.

- Allegheny Cemetery, Names Search. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Allegheny Cemetery archives.

- American Revolution Institute. Officers Represented in the Society of the Cincinnati. Washington, D.C.: American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Cincinnati.

- Baldwin, Leland D. (1937). Pittsburgh: the Story of a City, 1750–1865. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press. OCLC 557894587.

- Boucher, John N. (1908). A Century and a Half of Pittsburgh and Her People. New York, New York: The Lewis Publishing Co. OCLC 866209552.

- Chalfant, Ella (1955). A Goodly Heritage: Earliest Wills on an American Frontier. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press. OCLC 541599.

- Christman, W. U., ed. (February 2, 1939). Flashbacks from Post-Gazette Files. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- Coe, Letitia Tannehill (1903). History of John and Rachel Tannehill and Their Descendants [unpublished manuscript]. Fort Wayne, Indiana: Allen County Public Library.

- Dahlinger, Charles W. (1916). Pittsburgh: a Sketch of its Early Social Life. New York, New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 2519597.

- Dahlinger, Charles W. (1919). A Place of Great Historic Interest: Pittsburgh's First Burying-Ground. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: (no publisher given). OCLC 63680776.

- Darlington, Mary C., and others (1892). Fort Pitt and Letters from the Frontier. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: J.R. Weldin & Co. OCLC 1847480.

- Evans, Henry O. (1944). "The Penns' manor of Pittsburgh." The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, v. 27, nos. 3–4. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania. ISSN 0043-4035.

- Everett, Edward (1949). "Jeffersonian democracy and the tree of liberty, 1800–1803." The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, v. 32, nos. 1–2. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania. ISSN 0043-4035.

- Ford, Worthington C., ed. (1905). Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, v. 2. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. OCLC 261514.

- Ford, Worthington C., ed. (1906). Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, v. 5. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. OCLC 261514.

- Ford, Worthington C., ed. (1909). Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, v. 13, 14. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. OCLC 261514.

- Ford, Worthington C., ed. (1916). Thomas Jefferson Correspondence Printed from the Originals in the Collections of William K. Bixby. Norwood, Massachusetts: The Plimpton Press. OCLC 513105.

- Foster, Morrison (1932). My Brother Stephen. Indianapolis, Indiana: private printing. OCLC 1330553.

- Govtrack. (2004). Rep. Adamson Tannehill, Former Representative for Pennsylvania's 14th District. Washington, D.C.: Civic Impulse, LLC.

- Harper, Frank C. (1931). Pittsburgh of Today, its Resources and People. New York, New York: The American Historical Society, Inc. OCLC 2860230.

- Hentz, Tucker F. (2006). "Unit history of the Maryland and Virginia Rifle Regiment (1776–1781): Insights from the service record of Capt. Adamson Tannehill." Military Collector & Historian, v. 58, no. 3. Washington, D.C.: Company of Military Historians. ISSN 0026-3966.

- Heth, William (May 18, 1777). Daniel Morgan general orders, orderly book of Major William Heth. Richmond, Virginia: Virginia Historical Society.

- Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania (1944). "Historical society notes." The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine, v. 27, nos. 3–4. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania. ISSN 0043-4035.

- Kellogg, Louise P. (1917). Frontier Retreat on the Upper Ohio, 1779–1781. Madison, Wisconsin: State Historical Society of Wisconsin (John Gibson to Benjamin Biggs, November 1, 1780). OCLC 631162203.

- Killikelly, Sarah H. (1906). The History of Pittsburgh: its Rise and Progress. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: B. C. & Gordon Montgomery Co. OCLC 11201696.

- Long's Provisional Rifle Co. pay roll (July 1777). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 93, microcopy M246, roll 133.

- Maryland Historical Society (1900). Archives of Maryland: Muster Rolls and Other Records of Service of Maryland Troops in the American Revolution (1775–1783), v. 18. Baltimore, Maryland: The Lord Baltimore Press. OCLC 630418722.

- Maryland Historical Society (1927). "A muster roll of Captain Thomas Price's Company of rifle-men in the service of the united colonies." Maryland Historical Magazine, v. 22, no. 3. Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland Historical Society. ISSN 0025-4258.

- Metcalf, Bryce (1938). Original Members and Other Officers Eligible to the Society of the Cincinnati, 1783-1938: with the Institution, Rules of Admission, and Lists of the Officers of the General and State Societies. Strasburg, Virginia: Shenandoah Publishing House, Inc. OCLC 1538617.

- Miller, Annie Clark (1927). Chronicles of Families, Houses and Estates of Pittsburgh and its Environs: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (no publisher given). OCLC 1547877.

- Mulkearn, Lois, and Pugh, Edwin V. (1954). A Traveler's Guide to Historic Western Pennsylvania: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania University of Pittsburgh Press. OCLC 1336738.

- Pennsylvania 1812 Electoral College. A New Nation Votes, American Election Returns, 1787–1825. Worcester and Medford, Massachusetts: The American Antiquarian Society and Tufts Archival Research Center.

- Rawlings to Congress (November 28, 1785): Papers of George Washington. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 360, microcopy M247, roll 51, item 41, v. 8.

- Rawlings to Washington (August 1778). Papers of George Washington. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 360, microcopy M247, roll 51, item 41, v. 8.

- Sons of the American Revolution (1903). Year Book of the Pennsylvania Society, Sons of the American Revolution. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Spahr & Ritscher. OCLC 1018142189.

- Tannehill, James B. (1940). Genealogical History of the Tannahills, Tannehills and Taneyhills. Washington, D.C.: Gibson Bros., Inc. OCLC 1298766782.

- Thurston, George. H. (1888). Allegheny County's Hundred Years. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: A. A. Anderson & Son. OCLC 62594199.

- Twohig, Dorothy, ed. (1996). The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, v. 5. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia (Adamson Tannehill to Tobias Lear, March 8, 1790). OCLC 490886130.

- United States Congress. Adamson Tannehill in Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress.

- U.S. Congress, Pennsylvania 1812. Mapping Early American Elections. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress.

- U.S. Congress, Pennsylvania 1814. Mapping Early American Elections. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress.

- Walkinshaw, Lewis C. (1939). Annals of Southwestern Pennsylvania. New York, New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co. OCLC 865591627.

- Williams, Glenn F. (2005). Year of the hangman: George Washington's campaign against the Iroquois. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing, LLC. OCLC 59138596.

- Wilson, Erasmus, ed. (1898). Standard History of Pittsburg [sic], Pennsylvania. Chicago, Illinois: H.R. Cornell & Co. OCLC 191327658.

- Wright, Robert K. Jr. (1983). The Continental Army. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History Publication 60–4–1, U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 8806011.

External links