Adjua Gyapiaba | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1820 |

| Died | (aged 60) |

Adjua Gyapiaba, also known as Ajua Japiaba, Api-jaba and Afi Jaba, was a woman from Elmina in contemporary Ghana, who after a heated argument with a fellow Elminan was expelled by the Dutch colonial authorities to Suriname, where she eventually acquired fame as a herbalist and diviner.

Biography

Little is known about the early life of Adjua Gyapiaba other than that she was born in Elmina to Kwabena Gyapia.[1] While she was working as a trader in the Asante capital of Kumasi, she became embroiled in an argument with the wife of Elmina trader Kwamena Ankwanda that grew so heated that both women called each other donko, meaning "slave". When Kwamena Ankwanda tried to intervene on behalf of his wife, Gyapiaba allegedly swore an oath on the Asantehene that all Elminese were slaves of Asante, as were the inhabitants of Cape Coast. This caused great controversy among the Elminese in Kumasi, as she effectively called into question the legitimacy of the Elmina government.[2]

Swearing an oath was a serious affair in the Gold Coast society of the day, and since she had sworn an oath on the Asantehene, Gyapiaba was indicted before an Asante court, which fined her 1-pound 14 Engels. As Gyapiaba's oath was favourable to the Asante, she was presented with the money by Poku, a spokesman of Asantehene Kwaku Dua I.[3]

In Elmina, Gyapiaba's oath was taken much more seriously, however. Two envoys, one representing the native Elmina government and one representing the Dutch colonial government, were sent to Kumasi, urging the Asantehene to send Gyapiaba back to Elmina. After protracted negotiations, Gyapiaba was sent back to Elmina and immediately put in prison. The Dutch procurator fiscal W.G.F. Derx was reluctant to try Gyapiaba, but eventually succumbed to pressure by the Elmina government, which held that if there had not been a Dutch fort, Gyapiaba would have been burned at the stake.[4]

A year after the argument in Kumasi had taken place, on 7 November 1849, Governor Anthony van der Eb sentenced Gyapiaba "in accordance with African laws and local customs, suitably amended," to lifelong banishment in the East or West Indies for "serious calumnies and diatribes against the Dutch Government, the Elminese African government and the whole population of this place."[5]

Banishment to Suriname

Execution of the verdict took until early 1851 to materialize, as a suitable vessel had to be found that could take Gyapiaba into exile. Finally, on 15 March 1851, Gyapiaba arrived in Suriname. Although banishments had not been uncommon in the days of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the arrival of Gyapiaba three decades after the end of the slave trade posed the colonial authorities with some difficulties. It proved hard to find an Akan interpreter for Gyapiaba's deposition, and when this interpreter was eventually found, Gyapiaba stated that she did not know why she was exiled.[6] The Governor of Suriname requested the Minister of the Colonies that for future cases "no deportees from the Coast of Guinea be sent to his colony, as they refused to work and had to be supported at the cost of the colony."[5]

In February 1859, the Governor reported that Gyapiaba had been earning a living as a tradeswoman for a long time and that she was not supported by the government any longer. In 1862, she was given use of a yard on the Gemenelandsweg in Paramaribo where she was charged low rent, on account of indigence. In March 1869, she was allowed to inhabit the land free of charge, on account of her ill health.[7]

In 1868, she petitioned King William III of the Netherlands to let her return to Elmina, but despite the fact that the governors of both Suriname and the Gold Coast had no objections to this, no decision was taken. Meanwhile, Gyapiaba had acquired fame in Suriname as a herbalist and diviner. There were rumours she was a princess in her native country and her services were highly sought after by all layers of society.[8] She is said to have been on friendly terms with Governor Cornelis Ascanius van Sypesteyn, and frequently organized dance parties where she attracted attention with her African, non-Creole dance.[9][10][11] Others recollect that she rode through Frimangron on a goat while offering her services.[12][13]

Legacy

In 2007, the Surinamese government decided to rename the Nepveustraat in Paramaribo, which was named after a colonial governor of Suriname, to Afi Jabastraat.[15]

Notes

- ↑ Ten Hove 1996, p. 168.

- ↑ Baesjou 1979, p. 46.

- ↑ Baesjou 1979, p. 47.

- ↑ Baesjou 1979, p. 48.

- 1 2 Baesjou 1979, p. 49.

- 1 2 Vrij 2001, p. 118.

- ↑ Vrij 1995, p. 8.

- ↑ De Drie 1985.

- ↑ Penard & Penard 1913, p. 182.

- ↑ Vrij 1995, p. 9.

- ↑ "Nog iets over Api-jaba". De West: nieuwsblad uit en voor Suriname. Paramaribo. 29 September 1916. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Blakely 1992, p. 64.

- ↑ Van Kempen 2002, p. 136.

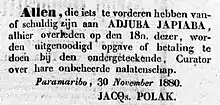

- ↑ Polak, Jacques (30 November 1880). "Allen die iets te vorderen hebben van of schuldig zijn aan Adjuba Japiaba..." Surinaamsche courant en Gouvernements advertentie blad. Paramaribo. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Visser, Marieke (July 2007). "Suriname geeft straten nieuwe namen". Historisch Nieuwsblad. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

References

- Baesjou, R. (1979). "Dutch 'irregular' jurisdiction on the 19th century Gold Coast". African Perspectives. 1979 (2): 21–66.

- Blakely, A. (1992). Blacks in the Dutch World: The Evolution of Racial Imagery in a Modern Society. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253214335.

- De Drie, A. (1985). "prensès Apiaba". In Guda, T. (ed.). Sye! Arki Tori!. Paramaribo: Ministerie van Onderwijs, Wetenschappen en Cultuur. pp. 126–130.

- Ten Hove, O. (1996). "Creools-Surinaamse familienamen: De samenstelling van de Creools-Surinaamse bevolking in de negentiende eeuw". OSO. Tijdschrift voor Surinaamse Taalkunde, Letterkunde en Geschiedenis. 15 (2): 166–180.

- Van Kempen, M. (2002). Een geschiedenis van de Surinaamse literatuur. Deel 3. Paramaribo: Uitgeverij Okopipi.

- Penard, F.P.; Penard, A.P. (1913). "Surinaamsch Bijgeloof. Iets over Wintie en Andere Natuurbegrippen". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia. 67 (1): 157–189. doi:10.1163/22134379-90001787.

- Vrij, J.J. (1995). "An Elminan political exile in Suriname" (PDF). Ghana Studies Council Newsletter. 1995 (8): 8–9.

- Vrij, J.J. (2001). "Maroons, futuboi and free blacks: Examples of Akan immigrants in Suriname in the era of slavery". In Van Kessel, W.M.J. (ed.). Merchants, missionaries & migrants: 300 years of Dutch-Ghanaian relations. Amsterdam: KIT publishers. pp. 111–119. hdl:1887/4734.