Adolf Loos | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).jpg.webp) Loos c. 1904 | |

| Born | Adolf Franz Karl Viktor Maria Loos 10 December 1870 |

| Died | 23 August 1933 (aged 62) |

| Nationality | Austria, Austria-Hungary |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Looshaus, Vienna Villa Müller, Prague |

Adolf Franz Karl Viktor Maria Loos[1] (German pronunciation: [ˈaːdɔlf ˈloːs]; 10 December 1870 – 23 August 1933) was an Austrian and Czechoslovak architect, influential European theorist, and a polemicist of modern architecture. He was inspired by modernism and a widely-known critic of the Art Nouveau movement. His controversial views and literary contributions sparked the establishment of the Vienna Secession movement and postmodernism.[2][3]

Loos was born in Brno to a family of sculptors and stonemasons. His almost deaf father, a stonemason, died when he was 9 and played a role in Loos' interest in arts and crafts. Loos later presented with his father's hearing impairment and other health-related issues. His lack of hearing contributed to his solitary personality. Loos had three tumultuous marriages that all ended in divorce and was convicted as a pedophile in 1928.

With changing interests, Loos attended multiple colleges also due to his poor academics and his different desires, which proved to be useful by providing him a diverse skillset for architecture. After leaving his last university, Loos visited America and became strongly impacted by the Chicago School of Architecture, being inspired by the architect Louis Sullivan and his form follows function philosophy.

Loos then went on to write many literary pieces including the satirical piece The Story of a Poor Rich Man and his most popular manifesto, Ornament and Crime, which advocated smooth and clear surfaces in contrast to the lavish decorations of the fin de siècle, as well as the more modern aesthetic principles of the Vienna Secession, exemplified in his design of Looshaus, Vienna.

Loos became a pioneer of modern architecture and contributed a body of theory and criticism of Modernism in architecture and design and developed the "Raumplan" (literally spatial plan) method of arranging interior spaces, exemplified in Villa Müller in Prague. He died aged 62 on 23 August 1933 in Kalksburg near Vienna.

Early life

Youth

Loos was born into a family of artisans on 10 December 1870 in Brno, in the Margraviate of Moravia region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, today the eastern part of the Czech Republic. His father Adolf Loos was a German stonemason who died when Loos was nine years old.[4] His mother, Marie Loos, was a sculptor who later continued to carry on the stonemason business after her husband's death. Young Adolf Loos had inherited his father's hearing impairment and was significantly handicapped by it throughout his life, contributing to his solitary character.[5]

Education

Loos attended several Gymnasium schools and sought a variety of programs. In 1884, Loos began his studies at the Stiftsgymnasium Melk for only a few months after failing an exam.[6] He then studied mechanics at the Royal and Imperial State Technical College in Liberec, but dropped to pursue building technology. He then returned to mechanics again at State Crafts School in Brünn in 1889, and changed to architecture by studying at Dresden University of Technology from 1890 to 1893.[7][8][9] Loos ultimately did not receive any academic degree due to his sporadic education pursuits, poor academics, and his enrollment to the Austrian military in 1889.[7][8][10] His enrollment however also sparked some of Loos' interests, joining a dueling club in college.[6]

Loos' diverse educational background provided him with a vast skillset which proved to be useful. For example, he could comprehend masonry and craftsman work and its impact on architecture.[7] He additionally was acknowledged by many scholars and was treated highly in the architectural field due to his experience.[11]

Career

United States

Post college, Loos traveled to the United States and stayed there from 1893 to 1896 to learn about outside architecture.[12] He started in New York and financially supported himself by working as a mason, a floor-layer, and a dish-washer.[13][14] These jobs allowed Loos to move to the Philadelphia countryside with his uncle Benjamin, where he worked as a watchmaker.[14] Living on the countryside made Loos admire America's rural culture, but he later traveled to New York and Chicago to explore American architecture.[15]

On his first visit to Chicago, Loos was immediately inspired by the new American skyscrapers and the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893.[16] Specifically, he was inspired by the architect Louis Sullivan and the Chicago School of Architecture, approving of Sullivan's concept of form follows function in his essay Ornament in Architecture.[16]

Although Loos left America in 1896, he later became involved with Chicago in 1922. Inspired by Sullivan, Loos submitted a building design for the Chicago Tribune Tower Competition, where his design proposal followed a Doric column as the building's top, known as the Column Tower proposal.[17][18] While he did not win, his architecture inspired post modernism ideas.[17]

Vienna

Loos returned to Vienna in 1896 and made it his permanent residence. He was a prominent figure in the city and a friend of Ludwig Wittgenstein, Arnold Schönberg, Peter Altenberg and Karl Kraus.

Inspired by his years in the New World he devoted himself to architecture. After briefly associating himself with the Vienna Secession in 1896, he rejected the style and advocated a new, plain, unadorned architecture. A utilitarian approach to use the entire floor plan completed his concept. Loos's early commissions consisted of interior designs for shops and cafés in Vienna.

Architectural theory

Loos authored several polemical works. In Spoken into the Void, published in 1900, he attacked the Vienna Secession, at a time when the movement was at its peak.[19]

In his essays, Loos used provocative catchphrases and is noted for the essay/manifesto entitled Ornament and Crime, given in a lecture in 1910 and first published in 1913.[20] He explored the idea that the progress of culture is associated with the elimination of ornament from everyday objects, asserting, "the evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornamentation from objects of everyday use."[21] It was therefore a crime to force craftsmen or builders to waste their time on ornamentation that served to hasten the time when an object would become obsolete (design theory). Loos's stripped-down buildings influenced the minimal massing of modern architecture, and stirred controversy. Although noted for the lack of ornamentation on their exteriors, the interiors of many of Loos's buildings are finished with rich and expensive materials, notably stone, marble and wood, displaying natural patterns and textures in flat planes, executed in first rate craftsmanship. The distinction is not between complicated and simple, but between "organic" decoration, such as that created by indigenous cultures (Loos mentions African textiles and Persian rugs), and superfluous decoration.[22]

Loos was also interested in the decorative arts, collecting sterling silver and high quality leather goods, which he noted for their plain yet luxurious appeal. His glassware, produced by Lobmeyer, is still in production today.[23] He also enjoyed fashion and men's clothing, designing the interior of the famed Kníže of Vienna, a haberdashery. His admiration for the fashion and culture of England and America can be seen in his short-lived publication Das Andere, which ran for just two issues in 1903 and included advertisements for 'English' clothing.[19] In 1920, he had a brief collaboration with Frederick John Kiesler, an architect, theater and art-exhibition designer.

Loos House and other projects

From 1904 on, he was able to carry out big projects; the most notable was the so-called "Looshaus" (built from 1910 to 1912), originally for the Viennese tailor Goldman and Salatsch, for whom Loos had designed a store interior in 1898, and situated right across from the Habsburg city residence Hofburg Palace. The house, today located at the address Michaelerplatz 3, Vienna, and under monument preservation, was criticized by its contemporaries. The facade was dominated by rectilinear window patterns and a lack of stucco decoration and awnings, which earned it the nickname "House without Eyebrows"; Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria was said to have despised the modern building so much that he avoided leaving the Hofburg Palace through a main gate in its vicinity.[24] His work also includes the store of the men's fashion house Knize (built 1909–13), Am Graben 13, Café Museum (built 1899), Operngasse 7, Vienna, and the "American Bar" (built 1907–08), Kärntnerstrasse 10, Vienna.[25]

Loos visited the island of Skyros in 1904 and was influenced by the cubic architecture of the Greek islands. When the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed after World War I Loos was awarded Czechoslovakian citizenship by President Masaryk.[26] His main place of residence remained in Vienna. During the First Austrian Republic Loos became interested in public projects. He designed several housing projects for the City of Vienna, which was then nicknamed Red Vienna. From 1924 to 1928 Loos lived in Paris. He taught at the Sorbonne and was contracted to build a house for Tristan Tzara, which was completed 1925 on Avenue Junot 15, Paris. In 1928 he returned to Vienna.

Loos had an admiration for classical architecture,[27] which is reflected in his writings and his entry to the 1922 Chicago Tribune competition. Loos's submission was a massive doric column.[28]

Private life

Marriages

Loos was married three times. In July 1902, he married drama student Lina Loos. The marriage ended three years later in 1905. In 1919 when he was 49, he married 20-year-old Austrian-born Elsie Altmann, a dancer and operetta star and daughter of Adolf Altmann and Jeannette Gruenblatt. They divorced seven years later in 1926. In 1929 he married writer and photographer Claire Beck. She was the daughter of his clients Otto and Olga Beck, and 35 years his junior. They were divorced on 30 April 1932.[29] Following their divorce, Claire Loos wrote Adolf Loos Privat, a literary work of snapshot-like vignettes about Loos's character, habits and sayings, published by the Johannes-Presse in Vienna in 1936. The book was intended to raise funds for Loos' tomb.

Poor health

All his life, Loos suffered from a hearing impairment. When he was a child, he was deaf. He only acquired partial hearing at the age of 12.[30] By the time he was 50 he was again nearly deaf. In 1918 Loos was diagnosed with cancer. His stomach, appendix and part of his intestine were removed.[31]

Child sexual abuse

In 1928 Loos was disgraced by a pedophilia scandal in Vienna. He had commissioned young girls, aged 8 to 10, from poor families to act as models in his studio. The indictment stated that Loos had exposed himself and forced his young models to participate in sexual acts. He was found partially guilty in a court decision of 1928.[32] In 2008 the original case record was rediscovered and confirmed the accusation.[33][34]

Death and legacy

Adolf Loos exhibited early signs of dementia around the time of his court proceedings. A few months before his death he suffered a stroke. He died aged 62 on 23 August 1933 in Kalksburg near Vienna.[35] Loos's body was taken to Vienna's Zentralfriedhof to rest among the great artists and musicians of the city, including Schoenberg, Altenberg and Kraus, some of his closest friends and associates.[29]

Through his writings and his groundbreaking projects in Vienna, Loos was able to influence other architects and designers, and the early development of Modernism. His careful selection of materials, passion for craftsmanship and use of 'Raumplan'—the considered ordering and size of interior spaces based on function—are still admired.[36]

Major works

- 1899 Café Museum, Vienna

- 1904 Villa Karma, Montreux, Switzerland

- 1907 Field Christian Cross, Radešínská Svratka, Czech Republic

- 1908 American Bar (formerly the Kärntner Bar), Vienna

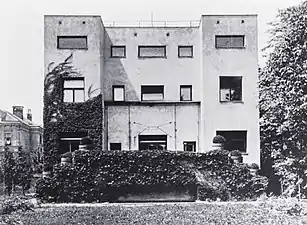

- 1910 Steiner House, Vienna

- 1910 Goldman & Salatsch Building, overlooking Michaelerplatz, Vienna (a mixed-use building known colloquially as the "Looshaus")

- 1913 Scheu House, Vienna (childhood home of modernist Elizabeth Close, née Scheu)

- 1915 Sugar mill, Hrušovany u Brna, Czech Republic

- 1915–16 Villa Duschnitz (re-model), Vienna

- 1917 House for sugar mill owner, Hrušovany u Brna, Czech Republic

- 1921 Mausoleum for Max Dvořák (unbuilt)

- 1922 Rufer House, Vienna

- 1925 Maison Tzara, house and studio, Montmartre, Paris, for Tristan Tzara, one of the founders of Dadaism

- 1926 Villa Moller, Vienna

- 1927 House (not built), Paris, for the American entertainer Josephine Baker

- 1928 Villa Müller, Prague, Czech Republic

- 1929 Khuner Villa, Kreuzberg, Austria

- 1932 Villa Winternitz, Na Cihlářce 10, Praha 5, Czech Republic

- 1928–1933 many residential interiors in Plzeň, Czech Republic

Expositions

- Adolf Loos - Exposition Du Cinquantenaire (23.02. – 16.04.1983) Paris (Institut Francais d´Architecture with Austrian Culture Institute, Paris) Ancienne Galerie, 6, rue du Tournon, 75006 Paris[37]

- Gründerzeit: Adolf Loos (11.04.1987 – 21.06.1987) Städtische Galerie der Stadt Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe, Germany[38]

- ADOLF LOOS (02.12.1989-25.02.1990) (joint exposition on 3 locations) Albertina, Historical Museum of the City of Vienna, Looshaus, Vienna[39]

- Adolf Loos „Private Spaces“ (14.12.2017 – 25.02.2018) Museu del Dessiny de Barcelona, Spain[40]

- Adolf Loos „Private Spaces“ (28.03.2018-24-06.2018) Caixa Forum Madrid, Spain[40]

- WAGNER, HOFFMANN, LOOS AND THE FURNITURE DESIGN OF VIENNESE MODERNISM (21.03.-07.10.2018) Imperial Furniture Collection (Hofmobiliendepot), Vienna[41]

- Adolf Loos: Private Houses (08.12.2020-14.03.2021) MAK Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna[42]

- „Loos2021“ (25.9.2020 – 30.5.2021) Loos Rooms at the Vienna Library, (former Boskovits flat) Bartensteingasse 9/5, 1010 Wien[43][44]

Furnishings Knize, Karlovy Vary branch Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018[40]

Furnishings Knize, Karlovy Vary branch Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018[40] Furnishing "House Duschnitz 1915" (Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018)[40]

Furnishing "House Duschnitz 1915" (Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018)[40] Adolf Loos Desk 1904 (Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018)[40]

Adolf Loos Desk 1904 (Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018)[40] Desk "House Friedmann 1907" (Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018)[40]

Desk "House Friedmann 1907" (Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018)[40] Furnishing "House Rufer 1922" Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018[40]

Furnishing "House Rufer 1922" Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018[40] Interior "House Steiner 1910" Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018[40]

Interior "House Steiner 1910" Barcelona, Madrid 2017 2018[40] Interior "Flat Georg Roy 1904", Hofmobiliendepot, Vienna 2018[41]

Interior "Flat Georg Roy 1904", Hofmobiliendepot, Vienna 2018[41] Furnishing "Flat Boskovits" (Loos2021, Vienna Library)[44]

Furnishing "Flat Boskovits" (Loos2021, Vienna Library)[44]

Bibliography

- Loos, Adolf (2 May 2007). On Architecture. Ariadne Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-57241-098-5.

- Loos, Adolf; Opel, Adolf (15 November 1997). Ornament and Crime: Selected Essays. Ariadne Press (CA). p. 204. ISBN 1-57241-046-9.

- Loos, Adolf (1982). Trotzdem, 1900–1930 (in German). G. Prachner. p. 218. ISBN 3-85367-037-7.

- Loos, Adolf; Heinrich Kulka (1931). Adolf Loos: Das Werk des Architekten (in German). Anton Schroll & Co, Neues Bauen in Der Welt, IV.

- Loos, Adolf (1983). Die Potemkin'sche Stadt: Verschollene Schriften, 1897–1933 (in German). Prachner. p. 231. ISBN 3-85367-038-5.

- Loos, Adolf (2013). Why a man should be well-dressed: Appearances Can be Revealing. Metroverlag. p. 231. ISBN 978-3-99300-040-0.

References

- ↑ Andrews, Brian (2010). "Ornament and Materiality in the Work of Adolf Loos" (PDF). Material Making: The Process of Precedent. p.438. Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ↑ Criminal Skins: Tattoos and Modern Architecture in the Work of Adolf Loos (PDF), Canales, Jimena and Andrew Herscher (2005) web, retrieved 3 October 2022

- ↑ "How Chicago's Tribune Tower Competition Changed Architecture Forever". ArchDaily. 3 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ↑ "Adolf Loos: Life and influence". Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ↑ Neutra, Richard (1980). Recuerdo de Adolf Loos (in Spanish). Carrer de la ciutat. pp. 9–10. hdl:2099/792. ISBN 978-3-85002-846-2. OCLC 1030566474.

- 1 2 Andrews, Brian (2010). "Ornament and Materiality in the Work of Adolf Loos" (PDF). Material Making: The Process of Precedent. p.438. Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Spotlight: Adolf Loos". ArchDaily. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- 1 2 Tournikiotis, Panayotis (2002). "Adolf Loos". Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9781568983424.

- ↑ "NGV Vienna Art and Design: Adolf Loos". www.ngv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2022-10-04.

- ↑ s.r.o, Via Aurea. "Adolf Loos | Architects | Brno Architecture Manual. A Guide to Brno Architecture". www.bam.brno.cz. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ↑ Maciuika, John V. (2000). "Adolf Loos and the Aphoristic Style: Rhetorical Practice in Early Twentieth-Century Design Criticism". Design Issues. 16 (2): 75–86. doi:10.1162/074793600750235804. ISSN 0747-9360. JSTOR 1511864. S2CID 57559630.

- ↑ Moss, K. (2010). "Constructing a Modem Vienna: The Architecture and Cultural Criticism of Adolf Loos". S2CID 190981131.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Tournikiotis, Panayotis (2002). "Adolf Loos". Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9781568983424.

- 1 2 Benedetto Gravagnuolo, Adolf Loos, Theory and Works (London: Art Data, 1995), 29.

- ↑ Bock, Ralf (2021). Adolf Loos: Works and Projects. Skira. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9788857244242.

- 1 2 Bototin, Norman & Laing, Christine, The Chicago World's Fair of 1893 The World's Columbian Exposition from Washington, DC: Preservation Press, 1992, pg. 20.

- 1 2 "How Chicago's Tribune Tower Competition Changed Architecture Forever". ArchDaily. 3 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ↑ "The Dancing Column". MIT Press. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- 1 2 "Adolf Loos: Writings". Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 18 November 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ↑ Janet Stewart, Fashioning Vienna: Adolf Loos's Cultural Criticism, London: Routledge, 2000, p. 173

- ↑ Loos & Opel 1997, p. 167.

- ↑ Loos & Opel 1997, pp. 173–174.

- ↑ Loos & Opel 1997, p. 9.

- ↑ "Haus ohne Augenbrauen | Stadtbekannt Wien | Das Wiener Online Magazin". Stadtbekannt.at. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "Architekturzentrum Wien". Architektenlexikon.at. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "Adolf Loos: Life and influence". Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ↑ Hanno-Walter Kruft. A History of Architectural Theory: From Vitruvius to the Present. Princeton Architectural Press, 1994 and Edward Chaney, Inigo Jones's 'Roman Sketchbook, 2006) page 361

- ↑ Oliver Wainwright (17 August 2011). "Top 10 unbuilt towers: Chicago Tribune Tower, by Adolf Loos". bdonline.co.uk/. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- 1 2 Loos, Claire Beck (2011). Adolf Loos – A Private Portrait. Los Angeles, CA: DoppelHouse Press.

- ↑ "Adolf Loos Facts". Biography.yourdictionary.com. 23 August 1933. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ "Biography of Adolf Loos, Belle Epoque Architect and Rebel". Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ↑ "[Rechtskräftiges Gerichtsurteil Adolf Loos] 7 Vr 5707/28/71". Members.aon.net. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ Christopher Long, Der Fall Loos. Amalthea 2015. ISBN 3850029085

- ↑ "FALTER » Ornament und Verbrechen". falter.at. 20 September 2011. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ↑ Bock, Ralf (2007). Adolf Loos. Geneve: Skira. ISBN 978-88-7624-643-2.

- ↑ "Adolf Loos: Raumplan". Royal Institute of British Architects. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ↑ Chaslin, Francois (1983). Adolf Loos. Pierre Mardaga Editeur. ISBN 2-8700-9174-5.

- ↑ Rödiger-Diruf, Erika (1987). Gründerzeit: Adolf Loos. Städtische Galerie Karlsruhe. ISBN 3-9233-4409-0.

- ↑ Rukschcio, Burkhardt (1989). Adolf Loos. Löcker Verlag Wien. ISBN 3-8540-9166-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fundacion Bancaria La Caixa, Museu del Dessiny (2017). Adolf Loos, "Private Spaces". Fundacion Bancaria La Caixa. ISBN 978-84-9900-190-6.

- 1 2 Ottilinger, Eva B. (2018). Wagner, Hoffmann, Loos (exhibition catalogue). Böhlau Verlag. ISBN 978-3-205-20786-3.

- ↑ "Adolf Loos, Private Houses". MAK Museum of Applied Art. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- ↑ "Loos2021". Tourist Info Vienna. Archived from the original on 3 November 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- 1 2 Ottilinger, Eva B.; Rukschcio, Burkhardt; Voglhofer, Stefan. "Loos2021 Review" (PDF). Austrian Federal heritage office. Bundesdenkmalamt. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

Further reading

- Bock, Ralf (2007). Adolf Loos. Geneve: Skira. ISBN 978-88-7624-643-2.

- Coppa, Alessandra (2013). Adolf Loos. Milan, Italy: 24 ore cultura. ISBN 9788866481485.

- Foster, Hal (2003). Design and Crime (And other diatribes). London: Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-453-3.

- Gravagnuolo, Benedetto (1995). Adolf Loos, Theory and Works. London: Art Data. ISBN 0-948835-16-8.

- Long, Christopher (2017). Adolf Loos on Trial. Prague: Kant. ISBN 978-80-7437-226-1.

- Masheck, Joseph (2013). Adolf Loos: The Art of Architecture. New York: I. B. Tauris. p. 263. ISBN 978-1-78076-423-8.

- Oechslin, Werner, "Stilhülse und Kern: Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos und der evolutionäre Weg zur modernen Architektur", Zuerich 1994.

- Ottillinger, Eva (1994). Adolf Loos Wohnkonzepte und Möbelentwürfe. Salzburg: Residenz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7017-0850-5.

- Rukschcio, Burkhardt; Schachel, Roland (1982). Adolf Loos: Leben und Werk. Salzburg: Residenz. ISBN 3-7017-0288-8.

- Adolf Loos: Our Contemporary (New York, Columbia GSAPP, 2013), eds. Y. Safran and Cristobal Amunategui. Published on the occasion of the traveling exhibition "Adolf Loos: Our Contemporary," a cooperation between Columbia University GSAPP in New York, the MAK in Vienna, and the CAAA in Guimaraes. Essays by Beatriz Colomina, Hermann Czech, Rainald Franz, Benedetto Gravagnuolo, Christopher Long, Can Onaner, Daniel Sherer, Philip Ursprung.

- Tournikiotis, Panayiotis (1996). Adolf Loos. Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 1-878271-80-6.

External links

- Works by or about Adolf Loos at Internet Archive

- Adolf Loos online exhibition images, podcasts and video about Loos's life and work. Royal Institute of British Architects

- Adolf Loos, Vienna 1900 & Austrian Modern Architecture TourMyCountry.com

- Adolf Loos biography 1870–1933 Archived 8 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine WOKA Lamps Vienna

- Muirhead, Thomas. "Adolf Loos seen through the keyhole". Building Design. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2007.