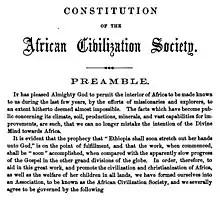

Preamble to the constitution | |

| Formation | 1858 |

|---|---|

| Founders | Henry Highland Garnet Martin Delany |

| Dissolved | 1869 |

| Type | Black-led organization |

| Purpose | Education and self-determination for the African diaspora |

| Headquarters | New York City |

Main organ | Freedmen's Torchlight People's Journal |

The African Civilization Society (ACS) was an American Black nationalist organization founded by Henry Highland Garnet and Martin Delany in New York City to serve African Americans. Founded in 1858 in response to the 1857 Supreme Court decision Dred Scott v. Sandford and a series of national events in the 1850s which negatively impacted African Americans, its mission was to exercise Black self-determination by establishing a colony of free people of color in Yorubaland. Additionally, the organization intended the colony to Westernize Africa, combat the Atlantic slave trade, and create a cotton and molasses production economy underwritten by free labor to undermine slavery in the United States and the Caribbean. However, the majority of African Americans remained opposed to emigration programs like theirs.

After the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, the organization shifted its focus and became the only Black-led organization to educate freedmen in the Southern United States. At their height in the 1860s, the organization supported Freedmen's Schools with a collective student body of approximately 8,000 people throughout the East Coast and Gulf Coast, employing 129 teachers with an annual budget of equivalent to $1,180,595 in 2022. Though most of their supporters lived in New York and Pennsylvania, auxiliaries and affiliates were established in England, Ohio, Connecticut, Ontario, and Washington, D.C. They published weekly and monthly newspapers with contributions from nationally-recognized Black leaders. After 11 years of service, the organization ceased operations in 1869.

Background

The American Colonization Society (ACS) was established in 1816 with the mission of encouraging African Americans, both enslaved and free, to emigrate to West Africa and establish a colony. These efforts eventually resulted in the founding of Liberia in 1821. The ACS consisted of a coalition of racists, humanitarians, and enslavers, most of whom either felt that Black people did not belong in the U.S. or that they did, but anti-Black prejudice would always keep them from achieving full American citizenship.[1] Black Americans broadly opposed the organization and the broader movement of African colonization with which it was affiliated.[2]

Despite this, some Black community leaders began to look upon both more favorably after Liberia declared independence under exclusively Black leadership in 1847.[3] Furthermore, there was a series of events which took place during the 1850s which led Black leaders such as journalist Martin Delany and Presbyterian minister Henry Highland Garnet to reconsider emigration. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 compromised the safety of free Black Americans by making them susceptible to kidnapping. The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 repealed the Missouri Compromise by opening up the possibility of expanding slavery into U.S. territories north of the 36°30′ parallel.[4]

Most alarming to Garnet and Delany, the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision by the Supreme Court of the United States denied any claims to constitutional rights for Black Americans.[5][4] In 1850, Garnet completed a lecture tour of the United Kingdom, speaking about the possibilities of undermining the economic viability of American slavery by encouraging the production of molasses and cotton using free labor in Africa.[6] In 1852, Delany published The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States, Politically Considered, in which he argued that Black Americans had no future in their own country. He asked "What can we do? What shall we do?" and "Shall we fly, or shall we resist?" Delany's conclusion was emigration.[7]

Colonization efforts

Garnet and Delany collaborated with other Black New Yorkers to establish the African Civilization Society (ACS) in September 1858.[2][6] The group envisioned Black colonists emigrating from the U.S. to the West African region of Yorubaland, where they would propagate Christianity and promote Westernization to the indigenous peoples of Africa.[2][8] In particular, the ACS was interested in undermining the Atlantic slave trade and the slave-based plantation economies of the U.S. and the Caribbean. They sought to do this by training Africans to produce cotton and molasses to compete with slave-produced products in European and American textile manufacturing and other global markets.[5][8] The ACS also promoted self-determination among the African diaspora, advocating in their constitution the "civilization and evangelization of Africa, and the descendants of African ancestors in any portion of the earth, wherever dispersed."[2][8] In 1859, Delany led a group along the Niger River in West Africa to explore possible sites for a colony. This expedition developed into a separate project called the Niger Valley Exploring Party.[9]

_pg638_THE_BIBLE_HOUSE_AND_OFFICES_OF_THE_CHRSTIAN_HERALD.jpg.webp)

In 1860, ACS director Theodore Bourne traveled to England to raise interest and funds for the proposed Yorubaland colony.[2] Local supporters created an affiliate group known as the African Aid Society. Because Delany was in England at the same time promoting the Niger Valley Exploring Party, British audiences were confused and found the two organizations in competition. Later that year, Elymas P. Rogers led a group of ACS members to West Africa to scout potential locations for a colony, but he died of malaria shortly after arriving in Liberia.[2] In April 1861, the ACS held a meeting to raise $10,000 (approximately equivalent to $325,704 in 2022)[10] to fund an emigration party of 20 Black Americans, led by Garnet, to Yorubaland.[11] Garnet traveled to England in August of that year to build interest in the project.[2] In November 1861, ACS supporters met with Delany, who offered a supplement to the organization's constitution to codify that the ACS would be controlled by the "colored people of America", though "their white friends" were welcome as "aiders and assistants". The adopted supplement affirmed that "the basis of the Society, and ulterior objects in encouraging emigration shall be: Self-Reliance and Self-Government on the Principle of an African Nationality–the African race being the ruling element of the nation, controlling and directing their own affairs."[12]

In 1864, the ACS moved their headquarters to Weeksville, Brooklyn, which was a free Black community established decades earlier as an alternative to emigration to Liberia.[3][13] Prominent Black Americans such as Frederick Douglass, James McCune Smith, and James W. C. Pennington were suspicious of the ACS because of their association with the white-led American Colonization Society, which was similar in mission and opposed by the majority of free Black Americans.[2][5] A local chapter, the New York State Colonization Society, kept their offices in the same building and provided several members on the eighteen-member ACS board of directors.[2] However, Garnet announced in 1860 that the ACS had no connection to the American Colonization Society, asserting that their mission did not disrupt slavery, whereas ACS worked against it explicitly.[14] At a May 1863 meeting of the ACS, Douglass charged that their constitution was "the fruits of the same vine as colonizationists" and "'the same Robfit Colonization' with a new skin".[15] Douglass had argued in a speech four years earlier that: "The African Civilization Society says to us, go to Africa ... To which we simply reply, 'we prefer to remain in America;'".[16]

Switch to education and dissolution

The outbreak of the American Civil War, and the subsequent announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, disrupted colonization societies such as the ACS and caused many of their supporters to focus on supporting the Union war effort in order to abolish slavery in the U.S. Garnet enlisted in the Union Army as a military chaplain and Delany as the major of a United States Colored Troops regiment.[17][18] Under the direction of Presbyterian clergyman and newly-selected ACS president George W. LeVere, the organization shifted its focus from colonization to educating formerly enslaved people, who were known as freedmen.[2] In 1863, they broadened their mission to include helping and educating people recently freed from slavery in the American South, Central and South America, the British West Indies and Africa. The new constitution, adopted on January 2, 1864, outlined a mission of ending the Atlantic slave trade and civilizing, uplifting, and Christianizing both Africa and the African diaspora.[19] Their programming reflected Black nationalist ideals, aiming to help Black people educate themselves, lead their own education programs, and create their own political and social institutions.[8] Between 1863 and 1867, the ACS were the only Black-led organization opening Freedmen's Schools in the South.[2][8]

During the war, Black activist and educator Junius C. Morel claimed that "The African Civilization Society is fully in the field". According to Morel, they were "holding meetings, collecting clothes, books, paper" to support freedmen and the organization was "making arrangements to send colored teachers just as fast as they can find the means and persons qualified to go".[20] By 1866, the group employed 69 teachers with a collective student body of 2,000 throughout the Northeastern United States.[8] By 1868, they employed 129 teachers and supported schools in Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana and Washington, D.C., with a collective student body of 8,000 and an annual cost of $53,700[21] (approximately equivalent to $1,180,595 in 2022).[10] Among those teachers were Maria W. Stewart, Laura Cardozo, Hezekiah Hunter, and his wife, Lizzie Hunter.[21]

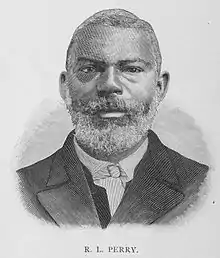

The ACS supported their educational efforts with a monthly newspaper, the Freedmen's Torchlight, which claimed it was "devoted to the temporal and spiritual interests of the Freedmen".[21] According to historian Judith Wellman, the paper's "contributors read like a blue ribbon list of Brooklyn's African American intellectual elite", including Rufus L. Perry, Henry M. Wilson, Morel, Delany and Amos Noë Freeman, minister of the Siloam Presbyterian Church.[21] The organization's other publication was a weekly newspaper called People's Journal.[5] ACS supporters lived primarily in Manhattan, Brooklyn and Philadelphia, but auxiliary groups formed in Ohio, Connecticut, Ontario and Washington, D.C.[13] Leadership and supporters grew to include Richard H. Cain, J. Sella Martin and Theodore L. Cuyler.[8][13] However, the ACS started declining financially in 1866 and disbanded in 1869.[8]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ James 2010, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Encyclopedia.com 2019.

- 1 2 Wellman 2014, p. 100.

- 1 2 Wellman 2014, p. 99.

- 1 2 3 4 African American Registry.

- 1 2 Wellman 2014, p. 106.

- ↑ Wellman 2014, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fenner-Dorrity 2008.

- ↑ Black Travel Alliance.

- 1 2 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ↑ Wellman 2014, p. 108.

- ↑ Wellman 2014, pp. 108–109.

- 1 2 3 Wellman 2014, p. 111.

- ↑ New York Times 1860.

- ↑ Wellman 2014, p. 109.

- ↑ Douglass 1859.

- ↑ Wellman 2014, pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Wellman 2014, p. 119.

- ↑ Wellman 2014, p. 110.

- ↑ Wellman 2014, p. 125.

- 1 2 3 4 Wellman 2014, p. 126.

Sources

- "African Civilization Society (AfCS)". Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. Encyclopedia.com. 2019. Archived from the original on January 26, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- "The African Civilization Society is Formed". African American Registry. Archived from the original on June 1, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- "The African Civilization Society: Response to its Opponents No Connection with the Colonization Society". The New York Times. May 16, 1860. Archived from the original on March 4, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- Douglass, Frederick (February 1859). "African Civilization Society". Teaching American History. Ashland University. Archived from the original on May 27, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- Fenner-Dorrity, Evelyn (November 19, 2008). "The African Civilization Society (1858–1869)". BlackPast.org. Archived from the original on March 20, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- "United States – Martin Robison Delany Led an Exploring Party to Niger Valley to Find a Homeland for African American Repatriation". History of Black Travel. Black Travel Alliance. Archived from the original on June 5, 2023. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- James, Winston (2010). The Struggles of John Brown Russwurm: The Life and Writings of a Pan-Africanist Pioneer, 1799-1851. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-4289-1.

- Wellman, Judith (2014). Brooklyn's Promised Land: The Free Black Community of Weeksville, New York. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-2415-6.

.jpg.webp)